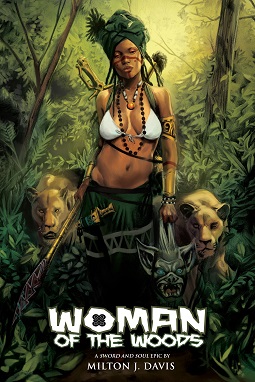

Self-published Book Review: Woman of the Woods by Milton Davis

This month’s self-published novel is Woman of the Woods by Milton Davis. Set in the land of Meji, a mythical land based on ancient Africa, Woman of the Woods is the story of Sadatina, a young woman of the Adamu. For centuries, the Adamu have been under attack by the nyoka, dark ape-like servants of the god Karan. Their only protection has been the Shosa, warrior-women blessed by their god, Cha, to fight the nyoka. Even as a young girl, Sadatina is stronger and faster than her older brother, better at hunting and fighting than any of the young men in her village. She eventually learns that this is because she is the forbidden daughter of a Shosa, and even untrained, she is blessed with their fighting ability. She needs those abilities when the nyoka come, slaughtering her adoptive family, leaving her to fend for herself, and eventually her village, with only the aid of two shumbas–jungle cats whom she has raised from cubs. It is as the village’s protector that she earns the name Woman of the Woods, since she protects the village while living apart from it. The Shosa find her there, and invite her to join them. At first she refuses, and returns home. At this point, the story skips forward twenty years, to where she has not only become a Shosa, but their military and spiritual leader.

The latter half of the book, where Sadatina is a mature warrior rather than an awkward girl, is a different story than the beginning. In a longer work, where the second half was a separate novel in its own right, the change would have been less jarring. As it is, it takes some getting used to for the reader to see Sadatina giving orders rather than rebelling against them. The latter half’s story is also larger, more epic story than the coming of age story which filled the first half of the novel. Rashadu, a nyoka who long ago turned against his master, has returned, and it is up to Sadatina to decide whether he is an enemy or an ally against Karan.

One of the strongest parts of this novel is the setting. Meji resembles Africa, with jungles and deserts, hot and humid or hot and dry, inhabited by a civilization as ancient as Egypt, though now in decline due to the depredations of Karan. While the Adamu, and to a lesser extent their rivals the Mosele, are the focus of this book, there are mentions of other civilizations, with their own bastions across the landscape, which whets your appetite for more exploring than will happen in this novel. More than anything, what works is that the people and their culture feel different from the typical Medieval (or Medieval with different trappings) culture that you often find in fantasy novels.

Unfortunately, the prose sometimes failed to live up to the promise of the setting. The dialogue, in particular, is stiff and formal, and never seemed to manage the casual ease that you’d expect in quiet moments between friends and family. Perhaps this was a stylistic decision, avoiding the sort of colloquialism that would be too modern and American, but if so, it didn’t quite work. On the other hand, with only a couple of exceptions, the fight scenes did work. They were fast-tempoed, and between Sadatina’s skill and her shumbas’ ferocity, they made for entertaining sword and sorcery fun.

Another issue was the sort of typos and continuity errors that are hard for authors to catch on their own. In particular, I kept being confused by the amount of time that passed. I’m still not sure how long it’s actually been since Karan began the war, and at one point Sadatina is away from the city of Wangaru for what seems to be a couple of months at most, but when she returns, we’re informed that she’s been away for a year. Some of these may have been my own misreadings, but it happened often enough that I’m pretty sure there were some mistakes.

But the most disappointing parts were the great ideas that didn’t really pan out. In particular, the subplots of Adande’s betrayal and Luanda’s hunt never lived up to their potential, resulting only in a few desultory fights and an unearned repentance. It would have been better to expand upon these subplots, and make them more fulfilling in their own right, or even cut one out completely to make room for the other.

A lot of the other aspects of the story did work. For example, the spirituality which plays a large role in the story. The Adamu are a religious people, and much of the book concerns their relationship with their god Cha. Both their ruler, the mansa, and their high priest receive visions and direct instruction from Cha, but it is not always clear, nor are the rulers always able to live up to the duties Cha gives them. It is the failure of the High Priest Ihecha at the beginning of the novel that leads to the dire straits the Adamu find themselves in at the latter half.

Of course, having a deity directly involved in the story is a challenge. But, wisely, the story focuses less on what Cha can and will do, than on the faith and failures of the people he calls. Although sometimes it’s not entirely clear why one succeeds while another fails. I was never quite clear on why Ihecha failed when first facing Karan, for example.

This faith is inextricably bound up in the magic system in the book. There is some magic in totems and spirits, but most of the power comes either from Cha or from Karan, who is also some sort of divine figure, though perhaps more devil than god. That doesn’t prevent the good guys from using the gris of their enemies against them, even going so far as to make a form of gunpowder. But in the end, it is Sadatina’s uneasy faith and strong sword arm against the power of Karan.

Woman of the Woods is available at Amazon (e-book and print), Barnes & Noble (e-book and print), MVmedia, and Kobo.

If you have a book you’d like me to review, please follow the submission guidelines here.

Donald S. Crankshaw’s work first appeared in Black Gate in October 2012, in the short novel “A Phoenix in Darkness.” He lives online at www.donaldscrankshaw.com.

[…] Self-published Book Review: Woman of the Woods by Milton Davis […]