When Aliens are Delicious: Murray Leinster’s “Proxima Centauri” and the Creepy Side of Pulp SF

What if the first aliens we encounter were made of chocolate? Crunchy, delicious, bite-sized chocolate. Imagine that during that all-important First Contact, you decided to take an experimental bite — because, one, chocolate aliens, and two, who would blame you? — and discovered they were so delicious they brought on raptures of ecstasy.

What if the first aliens we encounter were made of chocolate? Crunchy, delicious, bite-sized chocolate. Imagine that during that all-important First Contact, you decided to take an experimental bite — because, one, chocolate aliens, and two, who would blame you? — and discovered they were so delicious they brought on raptures of ecstasy.

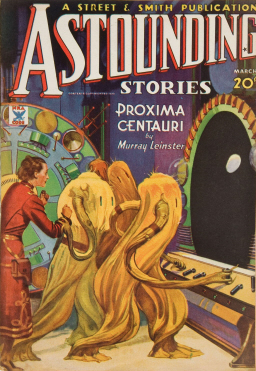

This is more or less the premise of Murray Leinster’s rip snortin’, force-ray filled space adventure “Proxima Centauri,” from the March 1935 issue of Astounding Stories. Except that the aliens are actually highly advanced carnivorous plants who have systematically hunted every form of animal life on their home planet to extinction, and the delicious, bite-sized aliens are us.

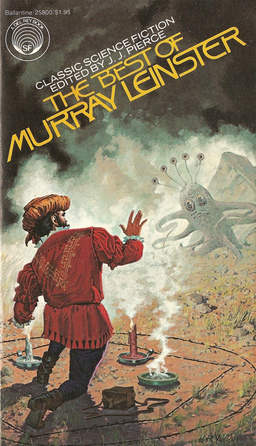

“Proxima Centauri” has been reprinted a few times, but I’d never read it. It came up in the comments on my June 20th article on The Best of Murray Leinster, the first of the Classics of Science Fiction series I’ve been exploring recently. A reader named Doug said:

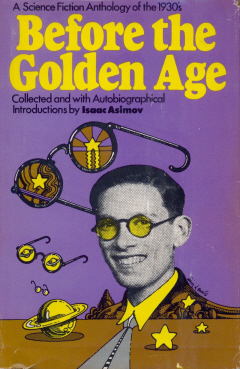

The one story of Leinster’s that impressed me the most was “Proxima Centauri.” Even if the main drive of the plot is pure pulp, the way he describes human behavior during the long trip adds a realism that counter balances the more fantastic elements (i.e. Plant Men). It’s aged incredibly well when you consider that it was written “Before the Golden Age” (I read this first in the same-named Asimov edited anthology).

Fletcher Vredenburgh concurred:

I was eleven when my dad bought and read the Leinster collection. When I asked him about it he said he didn’t think I’d like it. Fortunately, that only encouraged me to give it a try. Glad I did. The gloriously pulpy “Proxima Centauri” still creeps me out.

Well, that was enough for me. I dug out my treasured copy of Before the Golden Age and settled in to enjoy a classic tale of space travel and creepy aliens from a pulp master.

[Click on any of the pics in this article to embiggen.]

“Proxima Centauri” follows the exploits of Earth’s first starship, the Adastra, on the tail end of a 7-year voyage of exploration to our nearest neighbor system, and the star Proxima Centauri. The brilliant tech-head Jack Gary, our stalwart hero, has been picking up weird transmissions from dead ahead, and eventually discovers a spaceship cruising towards them in the darkness.

Something’s not right with the approaching craft. It’s attempting to be deceptive with its funky radio beams and stuff, and everybody knows that’s not how friendly aliens greet new arrivals. Sure enough, when they get close enough, the aliens fire a “radiation beam” at the Adastra.

The crew decides to play dead. The Centaurian ship docks and sends over a boarding party, which leads to a full-on boondoggle with force-beams and plant men — and the fateful moment when the first plant man takes a tentative bite from a juicy, delicious-looking human negotiator.

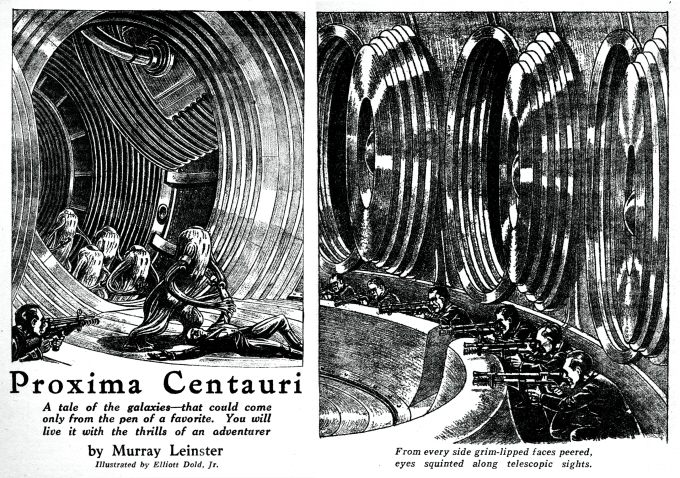

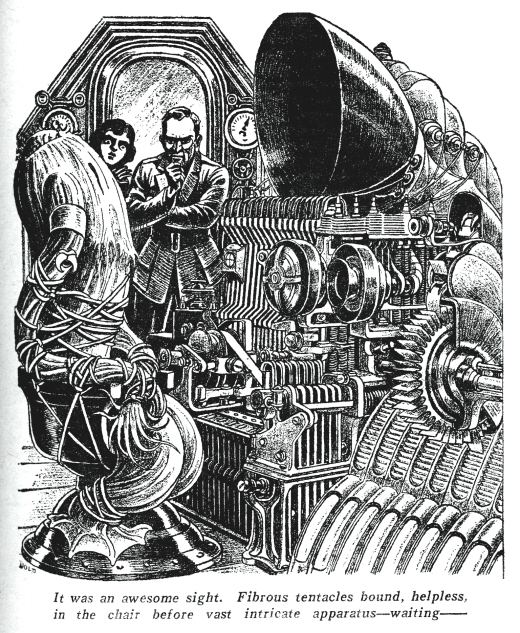

This is the very moment that Astounding‘s interior artist, Elliott Dold, elected to portray in the double-page spread he created for “Proxima Centauri”:

I don’t mean to spoil anything for you; but dude, this story is nearly 80 years old. If you’ve put off reading it this long, I’m gonna assume it probably wasn’t next on your reading list or anything. Right? Okay then.

So. The boarding party of nasty, hungry aliens is defeated, and the Centaurians hightail it. The crew ties up one of the alien prisoners with rope. Yeah, seriously, rope. I don’t know where they got rope on a starship either. But here, look:

Rope.

I love how officers on the Adastra dress like leather-clad Nazi goons from Raiders in the Lost Ark, too. Nice touch, especially since “Proxima Centauri” was written half a decade before the outbreak of World War II. Science fiction, always predicting stuff.

Anyway, once they get a Centaurian trussed up like a Christmas turkey, the crew figures out they’re mobile, carnivorous plants that feed on animals, and they regard humans as a highly prized food source — no more, no less. Worse, now that the Adastra has blundered into their system, the Centaurians are able to track their course back to an entire planet filled with juicy, tasty snacks. This is Bad News for Earth, as they’re entirely unprepared for invasion, and the Adastra has no means to warn them.

It’s up to the Adastra to set things right. Lots of space battles ensue, as the crew tries to undo the damage they’ve inadvertently done. There are desperate plans, astonishing discoveries, horrific setbacks, and romance. Sixth-grade I-like-you-do-you-like-me? romance, but still, romance. Here’s a touching scene where our hero Gary and second-in-command Alstair discuss their mutual feelings for Helen, the beautiful daughter of the commander of the ship:

He hung up the space suit. As they turned to go through the doorway their hands touched accidentally. They looked at each other and faltered. They stopped, Helen’s eyes shining. They all unconsciously swayed toward each other. Jack’s hands lifted hungrily.

Footsteps sounded close by. Alstair, second in command of the space ship, rounded a corner and stopped short.

“What’s this?” he demanded savagely. “Just because the commander’s brought you into officer’s quarters, Gary, it doesn’t follow that your Mut methods of romance can come, too!”

“You dare!” cried Helen furiously.

Jack, from a hot dull flash, was swiftly paling to the dead-white of rage.

“You’ll take the back,” he said very quietly indeed. “Or I’ll show you Mut methods of fighting with a force gun! As an officer, I carry one, too, now!”

Ho-boy. Either the language of romance was very, very different in the 1930s, or that’s some wooden dialog right there. Probably both.

Ho-boy. Either the language of romance was very, very different in the 1930s, or that’s some wooden dialog right there. Probably both.

I wish I could tell you that things brighten up a bit as the story progresses; but sadly, I can’t. That’s pretty much what you’re in for. If this story had been submitted to Black Gate 10 years ago, I would have tidied up the manuscript after that scene and sent Mr. Leinster a polite note telling him he sucked pretty bad.

The clunky prose isn’t the only obstacle standing in the way of the modern reader. From a modern viewpoint, this isn’t so much a SF tale as it is a tale of advanced super-science, in which the advanced super-science is kinda low tech. Waaay low tech.

All computations are done by hand, for example. Record keeping is with card catalogs. Space combat is mostly a lot of running away, because space weapons haven’t been invented yet.

Except by the hostile aliens, who slowly melt holes in the hull of the Adastra from millions of miles away. (Apparently evasive maneuvers haven’t been invented yet either — even the kind I have to do in my mini-van every time those damn kids play soccer on my street).

Now, I know this is pulp fiction. Written less than a decade after American science fiction had been pushed out into the world with the first issue of Amazing Stories. I get it. I don’t need a lesson in how to appreciate pulp SF. Despite this blemishes, Before the Golden Age remains, like, my favorite book ever.

My respect for Leinster remains undiminished by “Proxima Centauri.” This was written fairly early in his career — and this is the man who wrote “Exploration Team” 20 years later, after all. (I re-read that story fairly recently, and it held up marvelously well.)

And it’s not as if the story is a complete failure. Doug and Fletcher are entirely right that the aliens in “Proxima Centauri” are a spectacularly creepy lot.

And it’s not as if the story is a complete failure. Doug and Fletcher are entirely right that the aliens in “Proxima Centauri” are a spectacularly creepy lot.

In fact, they’re creepy even by modern standards. Early pulp SF was all about innovation, with every story stacked full of new speculations of just what was out there waiting for us. One of the clunkiest writers in all SF, E.E. “Doc” Smith, built nearly his entire career on being the first to hypothesize a true interstellar expedition, with The Skylark of Space and its sequels. And with “Proxima Centauri,” Leinster posits a relentless alien plant race driven by a tireless hunger.

Here’s Asimov, in his commentary from Before the Golden Age:

The thing I remember most clearly over the years about ‘Proxima Centauri’ is the peculiar horror I felt at the thought of a race of intelligent plants that lusted after animal food. It is almost an unfailing recipe for a startling science fiction story to begin by inverting some thoroughly accepted situation, something so ordinary as to be almost disregarded. Of course, animals eat plants, and of course, animals are quick and more or less intelligent, while plants are motionless and utterly passive (except for a few insect-eating plants, which can be disregarded). But what if intelligent and carnivorous plants fed on animals, eh?

In point of fact, Leinster goes much further than just imagining hungry aliens. Their culture treasures trophies made from dead animals in the same way that mankind lusts for gold. In drawing this parallel, Leinster strongly implies that gold lust is a perpetual state of all mankind, and in many ways we’re not that different than the tireless killers of his far star.

So is “Proxima Centauri” worth reading?

Ultimately, I think so. The ending in particular is a pleasant surprise, as Leinster manages to conceal a clever twist in his tale of heroic sacrifice and desperate conflict.

But to enjoy it, you’ll need a high tolerance for stiff prose and the conventions of pulp plotting. And if you haven’t got it (at least, not to the degree demanded by “Proxima Centauri”), I urge you not to give up on Murray Leinster. Leinster was known as “the Dean of Science Fiction” until his death in 1975 and he left us with many brilliant stories. The Best of Murray Leinster is a great place to start.

Wow, those illustrations are great. Yeah, my recent rereading only confirmed your judgment on the story. Still, the horror aspects are still wonderfully gruesome

Thanks Fletcher. And yes, it’s a relentlessly grim tale, especially the last half. Might make an effective modern horror film, if you could fix up that dialog. 🙂

John, you’re right. There’s a lot about this one that just hasn’t aged well. But it’s surprising how many of Leinster’s later stories have held up, and not just the ones in Del Rey’s “Best of” collection. NESFA did a good job of expanding the contents of the Del Rey volume about a decade ago in First Contacts: The Essential Murray Leinster. Still, there are other stories that weren’t included that haven’t aged too badly.

While most of the good stuff from the 30s and 40s has been collected, there are still one or two lost gems floating around. Asimov’s Great SF series is a good place to start, and I intend to look at those on my blog starting in a month or so.

> While most of the good stuff from the 30s and 40s has been collected, there are still one or two lost gems floating around.

> Asimov’s Great SF series is a good place to start, and I intend to look at those on my blog starting in a month or so.

Keith,

That’s a terrific series — I wish I had time to dig into it myself.

Shoot me a note when you get started; I’d love to follow along on your blog.

I remember this one very well. I last reread it about 5 years ago and for my tastes I think that it has aged fairly well. What I found to be the most interesting aspect of the story is the opening section where Mr. Leinster describes life aboard a ship that has many years of travel time and the affect of close quarters and boredom had/has upon personal relationships. I think that this alone shows a depth of understanding that was years ahead of most genre/pulp writing of that time.

And on a side note, “Before the Golden Age” ranks (IMHO) as one of the top ten SF antholgies of all time, and the Ballantine “Best of” series is for my money the best introduction to the wide spectrum of earlier SF that there’s ever been published.

> And on a side note, “Before the Golden Age” ranks (IMHO) as one of the top ten SF antholgies of all time, and the Ballantine

> “Best of” series is for my money the best introduction to the wide spectrum of earlier SF that there’s ever been published.

Doug,

Hear hear! Before the Golden Age isn’t just a worthy anthology – it’s a terrific way to get introduced to the joy of pulp literature, as I don’t think anyone has communicated the wonder of the early days of SF the way Asimov did.

I’m in the middle of reviewing the entire Ballantine “Best of” series now, and I agree completely that they are a fantastic way to introduce yourself to two generations of top-flight American SF and fantasy writers.

[…] Murray Leinster’s “Proxima Centauri” and the Creepy Side of Pulp SF […]

[…] finest volumes, The Best of Murray Leinster. More recently, I looked at his creepy pulp SF tale “Proxima Centauri” on August […]

[…] Howard’s “The Tower of the Elephant” The Shapes of Midnight by Joseph Payne Brennan When Aliens are Delicious: Murray Leinster’s “Proxima Centauri” and the Creepy Side of Pulp SF Professor Jameson’s Space Adventures, or Zoromes Make the Happiest Cyborgs The Best One-Sentence […]

[…] short work of Clark Ashton Smith (“The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis“), Murray Leinster (“Proxima Centauri“), and the fanzines that cover the pulps, like Fantasy Review. I have high hopes that The […]

[…] fictional starship bound for Proxima may have been by the mighty Adastra, in Murray Leinster’s “Proxima Centauri” (1935), which travels to Proxima for that most enduring of reasons: It is the “nearest of the […]

It’s fascinating how patterns repeat themselves. Here it is eight years later, and I’ve just read “Proxima Centauri” in “The Best of Murray Leinster” like you did. I’ve also been working through the Del Rey “Best of” series, but it’s slow going as I’ve been confined searching for them in local second-hand book shops.

“Proxima Centauri” is a fun story. For me the silliest part is the romance plot, which just happens to end with the hero Jack and his lady love legally married and alone on a paradise planet. A modern story might use Alstair as the lead character, grimly following him as he sacrifices everything, including his sanity, to save humanity.

Kevin,

I hadn’t thought of the modern take on Alstair, but you’re absolutely right. He’s villainous in his contempt for our stalwart hero, but he’s got his strong points. And his ending is certainly more tragic!

God help me, now I want to re-read this story. What have you done to me.