The Genesis of The Fall of the First World

I began work on The Fall of the First World in 1979, when I was twenty-six years old, at the suggestion of my agent at the time, who told me that, because of the tremendous popular success of the Thomas Covenant trilogy and of Terry Brooks’s The Sword of Shannara, publishers were eager to buy epic fantasy novels, particularly fantasy trilogies. I began to outline my own trilogy and compose the opening section. I started by incorporating story ideas already in my files. These included notes for a novel about the sinking of an ancient island-continent, perhaps Atlantis itself, to be called The Passing of the Gods. At the same time, I had long entertained the idea of writing a novel about the Third Crusade, so I included characters that borrowed from the historic figures of Richard Coeur de Lion and Saladin, who more or less wound up becoming King Elad of Athadia and Agors ko-Ghen of Salukadia.

I began work on The Fall of the First World in 1979, when I was twenty-six years old, at the suggestion of my agent at the time, who told me that, because of the tremendous popular success of the Thomas Covenant trilogy and of Terry Brooks’s The Sword of Shannara, publishers were eager to buy epic fantasy novels, particularly fantasy trilogies. I began to outline my own trilogy and compose the opening section. I started by incorporating story ideas already in my files. These included notes for a novel about the sinking of an ancient island-continent, perhaps Atlantis itself, to be called The Passing of the Gods. At the same time, I had long entertained the idea of writing a novel about the Third Crusade, so I included characters that borrowed from the historic figures of Richard Coeur de Lion and Saladin, who more or less wound up becoming King Elad of Athadia and Agors ko-Ghen of Salukadia.

Part of the original idea of my writing the Atlantis novel was to include characters that would suggest actual historical or legendary figures of Western culture — Helen of Troy, for instance; and the Wandering Jew or Flying Dutchman; the noble and arrogant Miltonian Lucifer; and the divinely inspired seer of truth, a Christ figure, a Siddhartha, a Black Elk. I found no way to include another culturally iconic figure, a dragon slayer from the mists of early time, be he St. George or Siegfried, but I had no desire, anyway, to populate such a novel with a mélange of stale operatic cardboard figures.

These were to be real people from a lost age, the echoes of whose lives persist into our own time, and who became personified in our myths and stories or who were to be incarnated endlessly in our culture as figures of universal fascination, notoriety, or wisdom. Their singular qualities immortalize them as remarkable representatives of humanity — their heroism and beauty, for example, or their spiritual insight or existential aloneness.

My desire to write a novel about the Third Crusade was an ambitious one because I wanted to model it on one of my favorite works of art, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, that wonderful novel that itself seems like a living thing. This was quite an ambition indeed on my part, but I followed through with this aspiration in writing The Fall of the First World, although any of us would be perfectly right to consider it an act of arrogance and perhaps of hubris.

Far and away, most of my fiction reading has been of the late nineteenth century realists and early modernists and naturalists — Tolstoy, Hardy, Crane, Dreiser — and includes authors as diverse as Jack London and Somerset Maugham. Two other influences bear mentioning: certain playwrights — the ancient Greek tragedians, Shakespeare, Marlowe, Ibsen, and O’Neill — and the cinema, particularly silent movies.

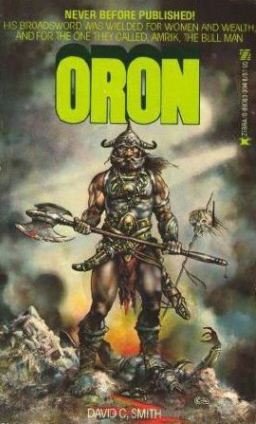

The influence of Shakespeare is evident in many of my early stories; I do think that I overdid the high diction and the characters’ declaiming in Oron, for example, and perhaps in this series, as well. But what better model could I have used for Agors’s wooing of Salia than that of Richard petitioning and winning the heart of Lady Anne Neville in Richard III? This appreciation of Shakespeare and the others has led to my at least attempting to invest my characters with some depth — even a creature such as Oron, who is plainly a heroic, even classically tragic, figure (but then, heroes are reflexively disrespected in our sophomoric, postmodern literary culture).

The influence of Shakespeare is evident in many of my early stories; I do think that I overdid the high diction and the characters’ declaiming in Oron, for example, and perhaps in this series, as well. But what better model could I have used for Agors’s wooing of Salia than that of Richard petitioning and winning the heart of Lady Anne Neville in Richard III? This appreciation of Shakespeare and the others has led to my at least attempting to invest my characters with some depth — even a creature such as Oron, who is plainly a heroic, even classically tragic, figure (but then, heroes are reflexively disrespected in our sophomoric, postmodern literary culture).

Regarding Ibsen, I feel that there is a bit of Nora Helmer and even of Hedda Gabler in, for instance, Red Sonja (the character whom I novelized, in partnership with Richard L. Tierney, in a series of six books). If that sounds obnoxious or self-serving, consider that my appreciation of the women’s movement in this country resulted from my familiarity with characters in Ibsen’s plays and George Eliot’s and Thomas Hardy’s novels, as well as with the history of early American cinema, in which a great number of the motion picture producers, directors, writers, and visionary actors (prior to 1920 or thereabouts) were women, often prominent women as important in their time as well-known women are in ours.

These brilliant artists a hundred years ago — Helen Gardner, Alice Guy, Lois Weber, and many others — fought powerfully entrenched attitudes of sexism and classism, attitudes far more oppressive than has been the situation in our more recent history.

All of these considerations find life in the character of Queen Salia. Is she a modern woman of her time, whenever that was?

Is she a victim? Is she determined to do better than her circumstances permit? Is she anxious to rebel and to follow that rebelliousness wherever it might lead? In rebelling, does she make choices that, ironically, work against her own intentions? The answer to all of these questions is, of course, yes.

The characters of Assia and Orain, too, I used to explore different facets of womanhood. And that these women form a trio is no accident. A number of sets of characters act in trio throughout this epic—the Athadian princes Elad, Cyrodian, and Dursoris, for instance; the spiritual figures Thameron, Asawas, and Eromedeus; the princes Elad (doubling — a theatrical term!), Agors, and Nihim; the courtiers Abgarthis and bin-Sutus and the selfless emissary Lord Thomo; the humanists Adred, Galvus, and Omos; and the warriors Cyrodian (another doubling), Nutatharis, and Kustos. A further trio: the three figures who are most abused and hurt by their fellow human beings — Assia, Omos, and Asawas—are the three characters who achieve the greatest spirituality.

As I revised the trilogy, I noticed that three couples, also, seem to balance each other in trio, although I don’t remember formally planning that: Assia and Thameron, Orain and Adred, and Omos and Galvus. (In any event, the three symbolism comes from a paper I wrote in 1973, during my junior year in college, in which I posited that three symbolism abounds around the character of Richard III. Gloucester appears in just one scene near the end of Henry VI, Part II. He has a few scenes in Henry VI, Part III. And then he has his own play as Richard III. I found quite a bit of three symbolism regarding Gloucester in these appearances of his, but whether it amounts to much of consequence, I am not sure. Perhaps it is simply coincidence, all of it.)

As I revised the trilogy, I noticed that three couples, also, seem to balance each other in trio, although I don’t remember formally planning that: Assia and Thameron, Orain and Adred, and Omos and Galvus. (In any event, the three symbolism comes from a paper I wrote in 1973, during my junior year in college, in which I posited that three symbolism abounds around the character of Richard III. Gloucester appears in just one scene near the end of Henry VI, Part II. He has a few scenes in Henry VI, Part III. And then he has his own play as Richard III. I found quite a bit of three symbolism regarding Gloucester in these appearances of his, but whether it amounts to much of consequence, I am not sure. Perhaps it is simply coincidence, all of it.)

I should also note that, in the initial publication of the trilogy, I consistently used the term “man” in its sense of referring to mankind as a whole, as humankind. This usage was still common in the early 1980s, although, even then, I should have made the effort to use a more general or inclusive term.

In this revision, therefore, I have generally replaced this use of the word throughout with such terms as “people,” “mankind,” “human beings,” and “humankind,” except when a character clearly means to use the term “man.”

The cinematic influence is apparent in everything I write, I think, but I was particularly amused, when I looked at The Fall to revise it after thirty years, at how evident this influence is, and in ways that I hadn’t recognized earlier. For example, I frequently insert italicized stretches of dialogue in a kind of voiceover to serve as memories for characters—and as flashbacks for the reader. And look at how many chapters open with a simple word, a place name to tell us where we are. Sugat. Elpet.

These are silent movie title cards, aren’t they? Or the introduction of the Salukadian empire, in part VI of The West Is Dying, with the sentence, “Ilbukar, the golden-shored, the early-skied, where the road ends.” This might as well be an intertitle from a D. W. Griffith production. Or the quick bit, as Sulos burns in the background, of the army escorting aristocrats to safety outside the city walls, when one wealthy person — whom, we do not know — takes a moment even in these deadly circumstances to retrieve a gold piece that has fallen onto the stones. Finally revolution has come, and this person is going to be buried alive, like all the other rich people, if the workers and peasants have their way — but, still, the rich person cannot resist grabbing that single dropped piece of gold.

So, with the Third Crusade and Helen of Troy in mind, and Sophocles and War and Peace, and D. W. Griffith and revolutionaries and suffragettes in shirtwaists and hobble skirts, I synopsized my big fantasy trilogy. I spent most of the early summer of 1979 doing it and wound up with fifty or so pages, single spaced, of chapters and scenes, along with the first part of the first book.

Unfortunately, by the time I turned this material in to my agent, I was told that “publishers have already bought their trilogies,” or words to that effect, and so I was out of luck.

Unfortunately, by the time I turned this material in to my agent, I was told that “publishers have already bought their trilogies,” or words to that effect, and so I was out of luck.

The agency continued to shop my outline around, however, which I greatly appreciated, and in late 1981, Pinnacle Books bought it at the behest of one of their editors at the time, Charles Rue Wood. For this, I am in his lasting debt. However, I had signed a contract only a little earlier to write three more novels for Zebra Books featuring the character Oron; my sword-and-sorcery novels were selling well for them then. The result was that I spent the next eighteen months writing six novels — nine, if you consider the size of each of the volumes of The Fall as being equivalent to that of two novels. I went to half-days on the job I was working and, to save even more time, asked my sister-in-law to type the final manuscript of the third Oron book, just so I could meet the deadline for it.

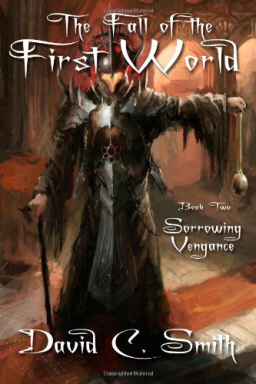

All of this effort wound up taking a heavy toll, and it is the reason why the manuscripts of The Fall of the First World were written rather quickly. The three books themselves appeared on bookstore racks in, respectively, January, September, and December 1983. And that, as it turns out, was pretty much the last anyone heard of The Fall of the First World. The trilogy dropped out of sight almost as soon as it was published. For a while, the first book could be found handily enough, but distribution of the next two was poor. The trilogy was never reviewed. It was nominated for no awards. It was as though it had never been written.

I had held high hopes for my epic trilogy because inflated fantasy stories had become so popular; ultimately, as we now know, these series of the 1980s served as the foundation for the corporate mainstreaming of the colossal world-building and Tolkeinesque fantasies we have seen during the past twenty-five or thirty years.

But the failure of The Fall to attract even a marginal audience, and my personal failure to gain even a modest toehold on a possible fiction-writing career, led to my decision, at the age of 31, to abandon trying to write full time (a long shot, under any circumstances) and instead find other work — first as an English teacher, then as an advertising copywriter, and later as a scholarly editor. (I have been most fortunate in finding jobs that fit my aptitudes.)

Now, after many years, I am very glad to have the chance to revise the trilogy and rectify some of the things that have needed to be changed or improved. For instance, I have been able to correct typos and other flaws that found their way into the original Pinnacle Books edition, such as the word “king” being capitalized as “King” throughout the text of the first book, never mind whether it is used in direct address or simply as an unattached noun. (I am afraid, though, that I haven’t been consistent in capitalizing most terms in direct address in this revision; I find it cumbersome to see line after line of “your Highness” and “my Lord” and so on in dialogue, even though these should properly be capitalized. It is jarring to my eye.

So you will have noticed that “my lord” and all of the many other honorifics are used in lower case throughout; elsewhere, however — for example, “Mother” and “General” — titles in direct address follow the rule. For such arbitrariness, I am blameworthy. So be it.)

So you will have noticed that “my lord” and all of the many other honorifics are used in lower case throughout; elsewhere, however — for example, “Mother” and “General” — titles in direct address follow the rule. For such arbitrariness, I am blameworthy. So be it.)

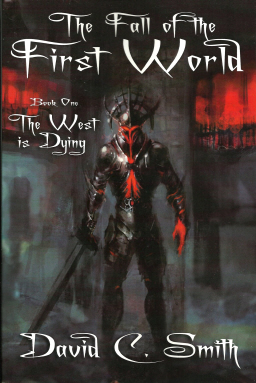

I have been able to reinstate my original title for the first volume. Pinnacle titled Book I The Master of Evil — why, I do not know, other than that it was likely thought to be commercially appealing. I much prefer my title, as ominous as it is: The West Is Dying. Certainly that personified concept is used as a leitmotif throughout the trilogy.

I have also been able to add depth to characters or supply details to enrich some scenes. This can be as minor as changing, in the prologue of the first book, “a young blond boy with a lute” to “a young blond man with a lute well cared for.” Even in an isolated tavern in what must feel like the end of the world, and surrounded by who knows what kind of human beings, this musician takes good care of the musical instrument by which he earns his livelihood.

And I have been able to rework passages that initially did not quite capture for me precisely what I was trying to emphasize or share.

I’ll give you an example. In the first chapter of The West Is Dying, immediately following the prologue, we are introduced to Count Adred. He stands at the rail of a ship and stares at the ocean. It is dawn; the sun is rising. Adred is gloomy because he is returning home to attend the funeral of a king and to see friends who he knows will be profoundly affected by the king’s death. Adred likes the sea and he likes to travel; it is analogous to life for him, the movement and the constant change of great waters and the deep; so as he looks at the ocean this morning, he is struck not only by the beauty of the sunlight on the water but also by the transience of such beauty.

Originally, this scene was written as follows:

There was a mist on the waves; the sunlight played in bars through it, like angled pillars of brilliant nonsubstance, striking the moving, restless waves with glimmering dewdrops of light, a myriad of them, flashing and glinting and disappearing upon the rolling surface to reappear elsewhere, a moment away, in an endless mesmeric dance of dreamery.

There are too many words here, and they get in one another’s way. Some of the words, such as “angled,” are too hard, which disrupts the tone of describing the panorama. I am trying to show how quick and busy the light is on the water, but I have overdone it and gone so far as to make up a word, “dreamery,” in a stretch to imply what is inside Count Adred’s mind.

I wound up reworking every word and phrase of this passage, changing Latin words to Anglo-Saxon ones, changing “reappeared” to “came back,” listening for the right sounds, and repeating words for punctuation because I do indeed want you to feel what Adred feels and see what he sees, to feel the weight of the water and to squint at the sunlight — feel the ocean-like strength of life and see it pass before you in those brilliant drops of light:

There was a mist on the waves. The early sunlight played in bars through the mist, falling in bright lines and teasing the waves with flashes of light that jumped everywhere, went away, and came back as though they were alive and dancing. They might have been human thoughts or human souls, those quick, dancing lights on the water, newly awake and joyful.

Too much? Overdone? Just right? I am not the one to say.

Too much? Overdone? Just right? I am not the one to say.

Still… Adred is looking at the ocean, looking at life, and imagining those bright sparks of light to be lives, here and gone, and shortly he and others on the ship will watch as hundreds of birds dive into the ocean, killing themselves. Already, the natural world has sensed the destruction coming, the deluge that will submerge many living things and swallow many lives the way the waves swallowed those birds. We have our foreshadowing. We know what life is about, and it is brief and bright and then taken away.

One other passage that I was eager to modify appears in the second volume, just before the prophet Asawas is arrested. I used, as a model for this scene of his preaching, the Nazarene’s “wars and rumors of wars” declaration in the King James version of the Christian Bible. This was a mistake on my part. I was in haste and I justified my paraphrase of the Nazarene’s words by telling myself that this language could be accepted generally or universally, rather than being of a culturally specific setting.

Clearly my doing so was an error. So now I have been able to replace those passages with a message that truly is universal, I hope — that being, whether we should regard others as mere things or fully, as other living human beings. This philosophy is one I have made my own, and I try hard to live by it.

Thus, I have at last been able to revise my forgotten trilogy and offer it again to readers courtesy of John Betancourt of Wildside Press and Rob Reginald of Borgo Press. I am extremely grateful to my friend Ted Rypel for suggesting that I contact the Wildside Press; to Dr. Fred Adams for his superb and insightful preface; to my wife, Janine, for the excellent maps she created of these lost empires; and to John and Rob, of course, for providing this opportunity to see the trilogy reprinted.

This article also appears as the Afterword to The Passing of the Gods, published 2013 by Borgo Press.

Are there e-book versions of these planned?

Thank you for sharing this. As both a fantasy fan and as a writer still trying for her first sale I am always fascinated by the creative process. Also, within the past month I read your contribution to Swords Against Darkness III and your first Red Sonja novel. Both were well done. I’ll have to look into getting the new editions of these books.

Wasp, I haven’t heard yet about any planned ebook versions. I’ve asked Wildside Press but haven’t heard back yet. Fingers crossed. They would do well as ebooks, I think.

Amy, thanks for looking into those old stories of mine. The Sonjas are all still popular, I see! Whatever you do, KEEP WRITING. You will grow and grow as a person and as a storyteller. It’s been extremely worthwhile for me on many levels. So even on off days when it seems as if you are fighting yourself, do keep at it.

Folks, I just heard from John Betancourt that the ebook versions will be out shortly.

Great news David!

Great news indeed. I just don’t really have the shelf space for everything I want to read anymore.

Looks like the first one finally arrived for Kindle over the weekend!

http://www.amazon.com/West-Dying-First-World-ebook/dp/B00EFYTT7M/ref=la_B001U4WUP8_1_4?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1376320306&sr=1-4