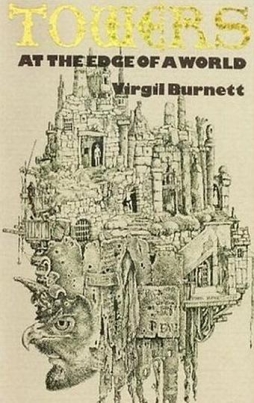

Virgil Burnett’s Towers at the Edge of a World

One of the distinct pleasures of book fairs and used book sales is finding an intriguing book you’ve never heard of. A greater and related pleasure comes when that book turns out to be quite good. Then, in reaction to that, there’s a melancholy that sets in from the fact that a worthwhile book is largely unknown. I’d like to think I can take the edge off that last sense by writing about some of these books here. So, given all that, a few words about Virgil Burnett’s Towers at the Edge of a World:

One of the distinct pleasures of book fairs and used book sales is finding an intriguing book you’ve never heard of. A greater and related pleasure comes when that book turns out to be quite good. Then, in reaction to that, there’s a melancholy that sets in from the fact that a worthwhile book is largely unknown. I’d like to think I can take the edge off that last sense by writing about some of these books here. So, given all that, a few words about Virgil Burnett’s Towers at the Edge of a World:

First published in 1980 by St. Martin’s Press and republished in 1983 by The Porcupine’s Quill with illustrations by the author, it’s a collection of 15 short stories and an introduction, all set in an imaginary French town in times ranging from the Dark Ages through to the near-present. It’s tied together by imagery and theme more than plot, both as a whole and in the individual stories. There’s little dialogue or drama, though more as the book goes on — it could be seen to be replicating the (supposed) historical development of a sense of character.

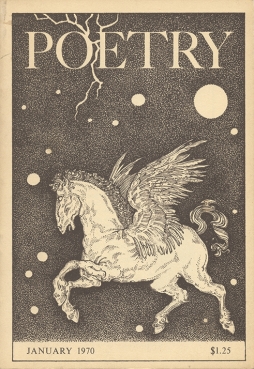

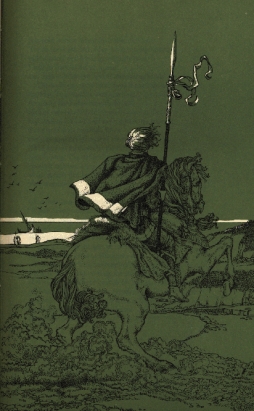

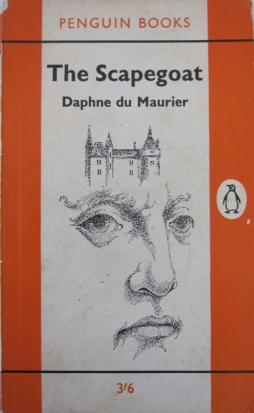

Born in Kansas in 1928, Burnett passed away last year. As well as being an author, teacher, and acquaintance of Stein and Joyce, he was an artist and art historian whose work included cover illustrations for Penguin (I’ve included examples of his art that I’ve found online alongside this article). From 1974 to his death, he lived in Stratford, Ontario, where he taught Fine Arts at the University of Waterloo. In addition to Towers, he wrote Skiamachia: A Fantasy (1982), A Comedy of Eros (1984), a collection of short stories called Farewell Tour (1986), and Scarbo Edge: A Romaunt (2008). He co-wrote two mystery novels with Bruce Barber under the name Bevan Underhill, The Bloody Man (1993) and The Running Girl (1994), and with Barber co-edited the 2004 anthology, Habaneras, which he published through his own Pasdeloup Press. In 2010, he published an essay on drawing, Object and Emblem. In 2003, a translation of his play Leonora was published in French; I can’t find a record of an English publication.

That’s what I’ve been able to learn about Burnett online. I’ll add that the art in Towers is remarkable. The drawings are almost pointillist in detail, but also gothic and exaggerated: very reminiscent of Aubrey Beardsley and Art Nouveau. Gamers might be reminded of Russ Nicholson at his most baroque.

That’s what I’ve been able to learn about Burnett online. I’ll add that the art in Towers is remarkable. The drawings are almost pointillist in detail, but also gothic and exaggerated: very reminiscent of Aubrey Beardsley and Art Nouveau. Gamers might be reminded of Russ Nicholson at his most baroque.

The structure of the novel, a series of linked short stories set in a fictional European locale, might sound like Le Guin’s Orsinian Tales. It reads more like the Gormenghast books, another work in prose by a visual artist; or perhaps like a less openly supernatural version of Tanith Lee’s Paradys sequence: highly worked language focusing on surfaces and textures, on memorable images. But also fable-like, direct; it’s both slow and fast, moments of decisive action that you might expect to serve as climax instead tossed off, described as afterthought. Character often emerges through detailed tableaux, as opposed to dialogue or drama. Here’s a knight in the late Middle Ages, suffering the pangs of love:

For more than a year Roscelin did not approach her. He occupied himself with riding and exercising with his weapons or, more dangerously, with sour brooding in his house. During these painful months he saw her only five times — in the great hall on feast days. The spectacle of the countess’s natural beauty splendidly embellished with the richest of her finery filled Roscelin with alternating sensations of longing and self-reproach. On the fifth day she appeared at the long banquet table in regalia more various and magnificent than any she had worn before. Her bright hair was braided and bound with gold. Precious pendants of silver filigree and intagliated gems dangled in radiant profusion about her throat and breast. Her robe was a bazaar of oriental fabrics. Above her heart a fibula decorated with a battling pair of ruby-eyed enamel monsters fixed a mantle so heavy with baroque pearls, carved ivory, and brilliants that she could scarcely hold herself erect beneath it. Like a sublime work of art, more chryselephantine goddess than woman, she posed beside her husband. Her face was as pure and expressionless as the great diamond that hung between her brows.

This story’s about the love of Roscelin and the countess, and there’s something appropriate in the fact that this paragraph begins with him and ends with her; with her being seen by him. That story, and I think the whole of the book, has a lot to do with appearances: disguise, dress, what is visible, and the whole question of what things look like — what imagery an image inspires in the minds of viewers.

This story’s about the love of Roscelin and the countess, and there’s something appropriate in the fact that this paragraph begins with him and ends with her; with her being seen by him. That story, and I think the whole of the book, has a lot to do with appearances: disguise, dress, what is visible, and the whole question of what things look like — what imagery an image inspires in the minds of viewers.

The stories aren’t all overtly fantasy, though the first features the hunting of a dragon. But there is a consistent feel of the unreal; of the extravagant and the parable. There are dream sequences and philosophical games and stories-inside-stories. The relative absence of dialogue, and the unpredictably languid pacing, creates a kind of hallucinatory sense, so that even stories that don’t have anything explicitly supernatural to them have the feel of a dark, unsettling fantasy.

Tying all the fictions together, over the span of centuries, is a theme of gender conflict and gender relations, specifically in the form of underground paganism and a poorly-suppressed witch-cult. The name of Montarnis has to do with Taramis, the Celtic god of thunder, here “master of the sky, of fierce hounds, and, during the winter months, of the Great Mother herself.” So the book can be read as a series of incidents depicting the conflict and subversion of male authority, especially religious authority, with and by female sexuality and mystery. Perhaps the central story of the book is the tale of an actual Amazon, who travels through a series of adventures out of Howard or Harold Lamb to end up a bandit queen in Montarnis — the whole seen through the eyes of various luckless males who encounter her along the way.

There seems to me to be an implied gender essentialism in the book, rarely stated outright; it arguably fits with the imagery and atmosphere, but sometimes feels reductive. More, there is what might be a kind of gender Manichaeism. Males desire females and vice versa, with little mention of homosexuality, or of the transgendered or intergendered. It seems to me that to say something meaningful about gender or sexuality, you need to consider the various forms these things take; if that’s the major theme of your book, then not dealing with these complexities weakens the whole.

There seems to me to be an implied gender essentialism in the book, rarely stated outright; it arguably fits with the imagery and atmosphere, but sometimes feels reductive. More, there is what might be a kind of gender Manichaeism. Males desire females and vice versa, with little mention of homosexuality, or of the transgendered or intergendered. It seems to me that to say something meaningful about gender or sexuality, you need to consider the various forms these things take; if that’s the major theme of your book, then not dealing with these complexities weakens the whole.

On the other hand, the book does not lack for thematic material of other sorts. Themes of art and storytelling are particularly apparent, perhaps; Montarnis is filled with creators, with performers male and female. But then also there are themes of death, a constant presence across the years, and of madness, which is much the same. There are almost too many themes, all handled obliquely, yet also all vividly present. The effect is like a flower-box overfilled with brilliant blossoms; beautiful, but hard to see the patterns.

Overall, though, the primal nature of these matters works with the oblique prose style to generate a convincingly mythic sense. The opening battle of old warrior and dragon seems to resonate through increasingly baroque refractions as the centuries pass. Historical detail and societal development are nodded at only in the most general sense; they exist merely to develop the ongoing story of Montarnis. In that sense, the novel’s setting is timeless, for all that it manifests differently in each chapter.

Overall, though, the primal nature of these matters works with the oblique prose style to generate a convincingly mythic sense. The opening battle of old warrior and dragon seems to resonate through increasingly baroque refractions as the centuries pass. Historical detail and societal development are nodded at only in the most general sense; they exist merely to develop the ongoing story of Montarnis. In that sense, the novel’s setting is timeless, for all that it manifests differently in each chapter.

Both ambitious and idiosyncratic, this was an unexpected pleasure to read. As a whole, the book succeeds. Stylistically strong and involving, it varies the structures of its individual stories nicely. It’s involving and affecting. It’s a strong piece of work and worth remembering.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] I’ve mentioned before that many novels by visual artists feature highly detailed descriptions and textures: worked surfaces. The Hearing Trumpet has a number of striking images, and certainly those images are important to the structure of the book, but contains few extended descriptions. Carrington instead gets at a dreamlike feel by not describing things, by simply stating what’s what and not trying to make them feel concrete. It’s a marvellously effective technique, allowing the images to live in the reader’s mind while also letting the book move quickly. There is a real visual imagination at work in the strange objects and settings Carrington presents, and the many strange metamorphoses objects and people undergo. But it’s never laboured, never sluggish. […]

Thank you for this. Virgil Burnett was my grandfather; I stumbled across this blog while looking for images of his work to show the kids I work with, and it gave me a real smile to see his work recalled fondly.

Thanks for the comment, James. It’s marvelous that you found us.

If you have any tales you’d like to share of your grandfather, we’d love to hear them.

He lead one hell of a life. I knew him as a stately sort of grandfather. He could be a curmudgeon, but he was also wonderful at using his art to distract and entertain his grandkids; my mum finally recalls a time when she came home to find he’d set me and my sister (at about 4 and 3 years old respectively) to polishing all of his shoes, which we thought was an awesome, fun privilege. I had a cardboard full helm that he’d made for me when I was about that age that I think was only disposed of when I headed off to college. He always said art had nothing to do with skill; there are no lazy artists.