King Arthur Revisited: Donald Barthelme’s The King

The legend of King Arthur has become one of literature’s greatest footballs, and it gets punted hither and yon with often quite careless abandon. Legions of celluloid spinoffs litter the vaults of Netflix, and on the printed page, one can select from heavyweights like Mallory, White, or Steinbeck to enjoy your Age of Chivalry fix.

The legend of King Arthur has become one of literature’s greatest footballs, and it gets punted hither and yon with often quite careless abandon. Legions of celluloid spinoffs litter the vaults of Netflix, and on the printed page, one can select from heavyweights like Mallory, White, or Steinbeck to enjoy your Age of Chivalry fix.

Flying well under the radar is one of the twentieth century’s best known metafictional writers, Donald Barthelme. His story collections, including City Lights and Sixty Stories, are classics of the form, endlessly inventive, cartwheeling-freewheeling-Catherine wheeling lunacies that manage nonetheless to pack a surprising emotional punch.

Most of Barthelme’s output centered on short fiction, but every so often he ventured into the realm of the novel, as with his knowing, nudge-nudge/wink-wink Snow White and his unjustly forgotten Arthurian outing, The King.

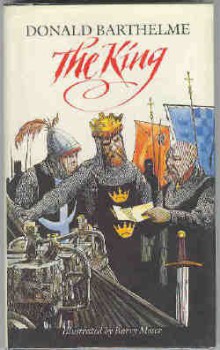

Released by Harper & Row in 1990 and featuring the evocative, jutting illustrations of Barry Moser, The King is an anachronistic treat from start to finish, and hilarious besides.

Just don’t enter these pages expecting everything to make sense. In Barthelme’s post H-Bomb world, sense and rationality are the enemy: they’re what got the “modern” world into these endless fixes in the first place.

sense and rationality are the enemy: they’re what got the “modern” world into these endless fixes in the first place.

Under Barthelme’s jaundiced yet merry eye, Arthur and Company are scooted forward in time to the Britain of World War II, and because none of the noble knights and ladies have aged at all, they now dwell concurrently with Adolf Hitler, Winston Churchill, and the British Royals of the day. Yes, the war is predominant, but Arthur must also find time to stave off a most ingenious railway strike, among other period distractions.

As a quintessentially American writer, Barthelme brings a rogue’s style to his British characters’ speech and readers can almost see the puckish grin on his face as he blends contemporary Brit-speak with antiquated utterances plucked straight from Mallory.

After Launcelot and the Black Knight (who in this telling truly is black, from Dahomey) fight, make up, and become allies, they “rose to their feet and clasped each other in their arms, and tears brast out of their eyen, and they fell to the ground in a swoon.” Two chapters later, Guinevere, who wishes “to go a-Maying,” gets into a windy debate with Mordred about Parliament, the Prime Minister, and constitutional government.

Shortly after, Launcelot pauses mid-battle with the Yellow Knight to discuss Fiona Lyonesse de Gales, who may or may not have been kidnapped by a giant. Musing, Launcelot says, “The giant’s name was Morgor. I believe I dealt with him. Had an extra eye in his left elbow. Damnedst thing I ever saw — messed up my footwork.”

Shortly after, Launcelot pauses mid-battle with the Yellow Knight to discuss Fiona Lyonesse de Gales, who may or may not have been kidnapped by a giant. Musing, Launcelot says, “The giant’s name was Morgor. I believe I dealt with him. Had an extra eye in his left elbow. Damnedst thing I ever saw — messed up my footwork.”

On the release of The King, Herbert Mitgang’s New York Times review hailed the book as “a daring tour de force. The King is pure Barthelme: deadpan, sly and cunning. Its barely concealed moments of seriousness make it his most learned and ambitious novel.”

Publishers Weekly, as is their wont, was more succinct. Their single-sentence review read, “Clever anachronisms and mock-Arthurian diction mark this madcap, absurdist 20th-century parable, in which Barthelme transposes King Arthur and his Round Table to 1940s England under Nazi bombardment.”

Barthelme did not live to see the publication of The King; he died in 1989 at the all-too-young age of fifty-eight. The gift of his writing remains, like Merlin in his cave or the unswerving bravery of Launcelot (here abandoned asleep beneath an apple tree), ripe for re-discovery.

Mark Rigney’s latest story for Black Gate was “The Find,” which Tangent Online called “reminiscent of the old sword & sorcery classics… A must read.” You can see what all the fuss is about here.