I Ain’t No Hero, See?

I’ve got a friend I’ve known since we were nine years old who often says that we weren’t really brought up by our parents (neither his nor mine), but by the books we read. I’m not sure if we were lucky or unlucky, but those books were full of, well, heroes. The first book I ever read, by the way, was Treasure Island – I think having seen the movie helped me with the hard parts.

I’ve got a friend I’ve known since we were nine years old who often says that we weren’t really brought up by our parents (neither his nor mine), but by the books we read. I’m not sure if we were lucky or unlucky, but those books were full of, well, heroes. The first book I ever read, by the way, was Treasure Island – I think having seen the movie helped me with the hard parts.

Aside: my parents didn’t come from cultures in which picture books were the norm, so we weren’t allowed to read them, nor comic books. Some illustration could be tolerated, but books with pictures on every page were for illiterate people.

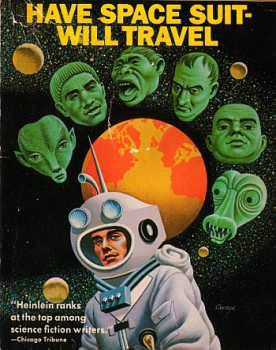

Then my brother recommended The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. That was the first fantasy book I ever read. Almost immediately after that I read Have Space Suit-Will Travel, my first SF book.

Not very long after these came Lord of the Rings – and every other Fantasy and SF book I could put my hands on. These were the books that raised me.

These books had something in common, something that I’ve spent some time talking about over the last few weeks. They have heroes. And by heroes I mean people who behave in a particular way, who have a particular attitude toward the world. I’ve talked about this idea in other places, and this is the best way I’ve found to express what I mean:

Genre fiction in general, Fantasy in particular, is the only contemporary literature in which characters can act honourably, without irony. Maybe they aren’t nice people, maybe they aren’t even good people – they’re certainly loaded down with flaws just like the rest of us. But they are honourable people. Even if they don’t think so themselves.

Obviously, I wasn’t aware of any of this while I was doing all that reading. At the time, I was just enjoying myself and unwittingly learning how to behave. It wasn’t until I was trained to analyze literature that I looked back over a long career of reading Fantasy and SF, and started to put my theory together.

Obviously, I wasn’t aware of any of this while I was doing all that reading. At the time, I was just enjoying myself and unwittingly learning how to behave. It wasn’t until I was trained to analyze literature that I looked back over a long career of reading Fantasy and SF, and started to put my theory together.

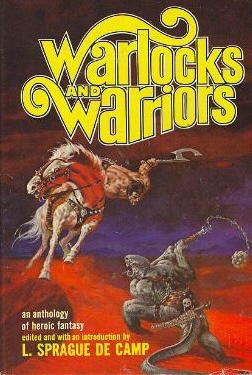

For me, the germ of my theory came in Warlocks and Warriors: An Anthology of Heroic Fantasy, edited and introduced by L. Sprague de Camp. There were three stories from this anthology which particularly intrigued me, and which give me shivers to this day: “Black God’s Kiss,” by C.L. Moore, “The Bells of Shoredan,” by Roger Zelazny, and above all, “Thieves House,” by Fritz Leiber.

From these stories I learned that heroes didn’t have to be royal and that the endings were sometimes ambiguous when it came to that happiness stuff. In particular, I learned these three things: That when your friends are in trouble you go back for them; that you hold by your code no matter what, even if that code causes you a lot of trouble.

Oh yeah, and payback is a bitch.

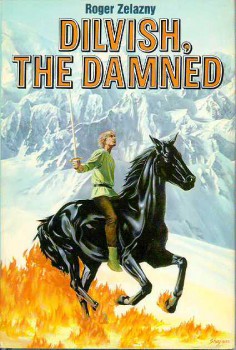

These three stories also gave me models for my own heroes, Jirel of Joiry (a woman!), Dilvish the Damned (someone no longer exactly human), and, most significantly, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser (worldly-wise comrades and partners).

I’ve often talked about the crime/mystery genre, and though I didn’t start reading them until later, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that sword and sorcery stories, as written by Leiber, Moore, Kuttner, de Camp, et al, were appearing in print at pretty much the same time as stories by people like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

In both we have protagonists (certainly not heroes in the classical sense) who inhabit places dangerous and dark, and who yet know how things operate, how to get by – and how to behave. The society around them is corrupt and cynical – they might even be a bit corrupt and a bit cynical themselves. So, they’re not heroes, but they are heroic, by the standards of their own worlds.

As Hammett puts it, “When a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it.” That’s a line that almost any Fantasy hero could say.

As Hammett puts it, “When a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it.” That’s a line that almost any Fantasy hero could say.

The worlds inhabited by today’s Fantasy and SF protagonists tend to be even more dark, and still more dangerous, than the worlds of my three classic favourites. But luckily for me – and for the stories I want to tell – the protagonists are still my kind of guys. Like Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe, like Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, they’re honourable people.

One last thing. There was something I found disappointing in the movie version of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. A couple of lines from the book got left out.

At one point Lucy says “We can’t just go home, not after this. It is all on my account that the poor Faun has got into this trouble,” and later on Peter says “This Faun saved my sister at his own risk . . . We can’t just leave him to be – to be – to have that done to him.”

I realize that a movie can’t contain every single line, nor even every single idea, that’s found in the book. But I find it significant that it’s this one that got left out. Stand by your friends, even if it’s risky.

That’s the real moral lesson of that series of books, and I’m sorry it didn’t make it into the movie. I don’t know why, maybe it says something about our society I’d rather not know. What I do know is this, these are lines Sam Spade would have approved of.

Violette Malan is the author of the Dhulyn and Parno series of sword and sorcery adventures, as well as the Mirror Lands series of primary world fantasies. As VM Escalada, she writes the soon-to-be released Halls of Law series. Visit her website www.violettemalan.com.

Can’t argue with any of that and it reminds me I need to go back and check out some old noir fiction.

Well, that’s about as righteous a post as I’ve seen here, or anywhere, in far too long.

One of the chief appeals of fantasy, and of much hardboiled fiction, is that the reader witnesses characters trying like hell to do the right thing.

Trying even against frightening odds, trying when it hurts, trying when they think they can’t try any more, and sometimes trying even when trying is meaningless outside of their own personal context.

As a young reader I found this inspiring, even moving. I haven’t changed a whole lot since then.

Oh yeah, I never let a mention of Heinlein’s Have Spacesuit, Will Travel go by without saying something silly like this: Lo, I have been working with books and in publishing since 1985, have a degree in English Lit, have written some, have edited some, and have grown gray around the muzzle reading what’s probably an unhealthy amount of books, and I am here to say that Have Spacesuit, Will Travel has the Greatest Final Sentence of Any Book I Have Ever Read.

You have to read the whole novel to get the full impact, but this is the Truth.

Thanks, Joe, and if you’re looking for something with the same attitude, but a bit more contemporary, there’s always Robert Crais’ Elvis Cole novels, or Robert B. Parker’s Spenser books, the early ones being the best.

John: For a second I thought you meant righteous in its negative connotation, and that made me blink, but I soon realized my mistake. Thank you for your insight.

PS, I looked at the last line of HSSWT, and I think that if you know the book well (as I do), it has the same effect. Thanks for that, too.

Great post – thanks! I felt the same way about something lefot out of the Lord of the Rings movies, again understanding that a tremendous amount simply couldn’t be included. When the Ring has been destroyed and Frodo and Sam are waiting to die (as they think), Frodo says, about Gollum, “But for him, Sam, I could not have destroyed the Ring. The quest would have been in vain, even at the bitter end. So let us forgive him!” Ley us forgive him – surely that should have been included.

Hear, hear! Nice post, and good point about the lines left out of TLtWatW.

Btw, I think a cool wristband would say “WWMD.” As in What would Marlowe do?

EMCGARGLE: I try not to get annoyed when this kind of thing gets left out, but when it speaks to the kind of honourable dealing that we’re talking about, it’s hard to understand why it happens. Unless, as I sometimes think, not enough people feel as we do. On the other hand, judging from William Goldman’s essays on screenwriting, it’s hard to say why anything goes in, or gets left out.

NICK: I could see myself explaining that a lot — and maybe to some of the wrong people. After reading this post, Tanya Huff suggests I have ribbons made for cons: Honour without Irony.

[…] to this idea, particularly Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melniboné, and, someone I mentioned last week, Roger Zelazny’s Dilvish the Damned. But these two, we might argue, are representatives of […]

According to interviews and articles that appeared at the time, the reason those lines were left out of the film version of The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe was specifically pressure from American conservative fundamentalist Christians.

C. S. Lewis made it clear that he considered the bonds of friendship far more important than even family bonds. That’s why those lines appear in the first Narnia books; in later Narnia books, characters often ignore or discard familial bonds, such as Eustace losing faith in his parents or Aravis happily abandoning her manipulative family. Lewis clearly valued family, but he considered some things more important, and friendship and loyalty are two of them.

This upset some powerful conservative fundamentalist groups, so they lobbied to have “Family Values” forcefed into the films. This is why those lines and the sentiments behind them vanish from the first film; it is also why they replaced the Professor’s wonderful discussion with Peter and Susan about logic and how logic supports Lucy’s claims with a pro-Family Values diatribe that they should trust Lucy merely because she is family, and logic and loyalty be damned.

Such lobbying eventually destroyed the film series, with the groups forcefully reducing The Voyage of the Dawn Treader from an insightful immram into a cookie-cutter Good vs Evil battle in which serendipity is replaced with divine puppeteering of our heroes.

Fortunately, long after the films have been relegated to dollar bins, the books will remain.

PHOENIX: I remember that I’d heard something along these lines at the time of the first movie’s release, but couldn’t recall the details. I like your reminder that Lewis valued family-of-choice over family-of-blood, as it fits with the overall theme of heroic fantasy, I think.

[…] I Ain’t No Hero, See […]