Further Tarzan-on-Demand: Tarzan the Magnificent

The Warner Bros. Archive Collection has taken good care of Tarzan fans. This manufacture-on-demand division of Warner Home Video offers all the films from the lesser-known Tarzan actors who followed Johnny Weissmuller in swinging from the jungle ceiling: Lex Barker, Gordon Scott, Jock Mahoney, Mike Henry, and the two seasons of the Ron Ely television story. The best of the lot for a more casual viewer is Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure (1959), but Tarzan the Magnificent from 1960 comes a close second to it. It’s not as lean and stripped-down as its predecessor, and director Robert Day lacks the same skill at pacing an action picture as John Guillermin, but the movie ranks among the top live-action Tarzan films ever made. And it’s just a darn good adventure film in general, with some surprising levels of violence and mature subtexts.

The Warner Bros. Archive Collection has taken good care of Tarzan fans. This manufacture-on-demand division of Warner Home Video offers all the films from the lesser-known Tarzan actors who followed Johnny Weissmuller in swinging from the jungle ceiling: Lex Barker, Gordon Scott, Jock Mahoney, Mike Henry, and the two seasons of the Ron Ely television story. The best of the lot for a more casual viewer is Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure (1959), but Tarzan the Magnificent from 1960 comes a close second to it. It’s not as lean and stripped-down as its predecessor, and director Robert Day lacks the same skill at pacing an action picture as John Guillermin, but the movie ranks among the top live-action Tarzan films ever made. And it’s just a darn good adventure film in general, with some surprising levels of violence and mature subtexts.

(Tarzan disambiguation notice: The movie has no connection to the Burroughs book of the same title published in 1939 that combines two separate novellas.)

Tarzan the Magnificent is the second movie of the series from producer Sy Weintraub, who created the “New Look” Tarzan that took the character back to his more adult and violent Edgar Rice Burroughs roots. Best of all, Tarzan got his full vocabulary returned to him, breaking over two decades of film tradition that ruled the Lord of the Jungle had to horribly misuse pronouns and exterminate helping verbs.

Weintraub’s “New Look” favored crime stories set in the African rainforest, which gave them a harsh and naturalistic feel. They also borrowed elements from the Western, and Tarzan the Magnificent is the most explicit example. The movie opens with a band of outlaws, an archetypal blood clan of murderous brothers under an obsessed patriarch, committing a hold-up in broad daylight. The criminals rob the pay office of a mining company in a small town, passing “Wanted” posters of themselves on the way in. Except for the African locals walking the dusty street, this might be any frontier town in a Western of the day. With veteran John Ford stock-company actor John Carradine in the role of the clan head, Abel Banton, it’s hardly much of a leap to see this taking place in a lawless American frontier town. Even the name “Banton” has a Western ring to it, echoing the Clantons from the story of the Gunfight at the OK Corral.

After the five Bantons escape from the town of Busai, a local policeman, Inspector Wyntors (John Sullivan) tracks them into the wilderness and takes hostage the favorite son, Coy (Jock Mahoney). The rest of the family ambushes the policeman and kills him in the shoot-out, but they don’t get Coy back: Tarzan (Gordon Scott) arrives and drives the Bantons away, killing one of the sons, Ethan (Ron McDonnell). Tarzan was a friend of Inspector Wyntors, so he plans to turn the criminal over to the authorities and give the reward money for his capture to Wyntors’s widow and children. Tarzan would’ve done this even if he had never met Wyntors because, well, he’s Tarzan and this is his jungle. Do not bring your evil here.

After the five Bantons escape from the town of Busai, a local policeman, Inspector Wyntors (John Sullivan) tracks them into the wilderness and takes hostage the favorite son, Coy (Jock Mahoney). The rest of the family ambushes the policeman and kills him in the shoot-out, but they don’t get Coy back: Tarzan (Gordon Scott) arrives and drives the Bantons away, killing one of the sons, Ethan (Ron McDonnell). Tarzan was a friend of Inspector Wyntors, so he plans to turn the criminal over to the authorities and give the reward money for his capture to Wyntors’s widow and children. Tarzan would’ve done this even if he had never met Wyntors because, well, he’s Tarzan and this is his jungle. Do not bring your evil here.

But delivering Coy to the police won’t be easy. The residents at the local staging post of Mantu are terrified of the Bantons’ retaliation for the death of Ethan, so Tarzan instead volunteers to escort Coy to the town of Kairobi. But the Bantons blow up the only boat on the river and kill its captain, forcing Tarzan to make the sixty-five mile mountain trek to reach his destination — and giving Abel Banton and his other sons a better chance of killing him.

Thus we have a classic plot structure used in many Westerns: “Escort the prisoner through the badlands.” This storyline appeared in movies such as 3:10 to Yuma, Ride Lonesome, and The Naked Spur. To add to the complications, Tarzan gets company for the trip that he doesn’t want: the people who originally planned to take the riverboat to Kairobi. Tarzan is happy to take the first mate from the boat, Tate (Earl Cameron), but it’s a different story with Ames (Lionel Jeffries), his wife Faye (Betta St. John), fallen doctor Conway (Charles Tingwell), and young Lori (Alexandra Stewart). Since Ames’s presence is necessary for the building of a dam in Kairoibi and the creation of numerous jobs, Tarzan gives in to his demands to accompany him — which means he has to give in to all their demands. The Ape Man should’ve stood firmer on this, since none of them are equipped to handle a jungle trek and they would only slow him down, but the movie wouldn’t have the same dramatic possibilities without the whole crew along.

The adventure that follows uses the chase formula from Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure, concluding in almost the exact same action sequence. But Tarzan the Magnificent switches the sides: instead of the villains bickering and falling apart, it is Tarzan’s band that bounces off each other and features the more shaded and ambiguous characters. John Carradine’s villain is a straightforward killer with no particular arc, which is different than the layered character of Slade played by Anthony Qualye in the previous movie. The major character journeys in Tarzan the Magnificent occur among Ames and Faye, with the latter transforming into a villainess over the course of the expedition as Coy Banton works his charms on her to break up the party and give him a chance to escape. Conway gets a compressed character arc, redeeming himself as a former doctor when he helps save a village woman’s life, but this occurs early on and afterwards Conway is just an extra finger on a trigger when Tarzan needs it. The only person on the expedition who doesn’t serve much purpose is Lori. She’s there to provide the “pretty blonde,” but she has no interesting relationships and only advances the plot when she needs rescuing — and that only happens once.

The adventure that follows uses the chase formula from Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure, concluding in almost the exact same action sequence. But Tarzan the Magnificent switches the sides: instead of the villains bickering and falling apart, it is Tarzan’s band that bounces off each other and features the more shaded and ambiguous characters. John Carradine’s villain is a straightforward killer with no particular arc, which is different than the layered character of Slade played by Anthony Qualye in the previous movie. The major character journeys in Tarzan the Magnificent occur among Ames and Faye, with the latter transforming into a villainess over the course of the expedition as Coy Banton works his charms on her to break up the party and give him a chance to escape. Conway gets a compressed character arc, redeeming himself as a former doctor when he helps save a village woman’s life, but this occurs early on and afterwards Conway is just an extra finger on a trigger when Tarzan needs it. The only person on the expedition who doesn’t serve much purpose is Lori. She’s there to provide the “pretty blonde,” but she has no interesting relationships and only advances the plot when she needs rescuing — and that only happens once.

Although billed deep in the cast list, with “Introducing” Gary Cockrell as Martin Banton mysteriously billed above him, Lionel Jeffries gives the most memorable performance as Ames. From the moment we meet him, we hate him: Ames is the pinnacle of the obnoxious colonial blowhard, bragging about his military achievements and condescending to everyone. His racism bursts out at one point when Tate tries to help him up and he barks at him to “Get your black hands off me!” In one infuriating conversation, he presents his life philosophy designed to denigrate anybody who isn’t him: “If a man reaches the top, if he’s the best, then he’s a success…. Let us put it this way. If you’re not first, you’re second. And being second-rate is not being a success.” When Conway responds that by such standards, most people in the world are not successes, Ames twists the knife: “That’s right.” The editing and direction in this scene perfectly sets up Faye Ames’s growing disgust with her husband and how easy it will be for Coy Banton to tug her loyalties to his advantage.

However, Ames ends up one of the surprises in the story: instead of ultimately “getting his,” he changes for the better as his assumptions about everyone else crash down around him. The “second-rate” people show themselves to be first rate, and Faye’s betrayal comes as a harsh sting about how he really does not have the control he thought he did. Jeffries nails the part, especially when he’s being insufferable, but the way Gordon Scott’s Tarzan reacts to him tells us a great deal about the Ape Man as well. It’s understated “anti-chemistry” that gives the film its best character moments.

However, Ames ends up one of the surprises in the story: instead of ultimately “getting his,” he changes for the better as his assumptions about everyone else crash down around him. The “second-rate” people show themselves to be first rate, and Faye’s betrayal comes as a harsh sting about how he really does not have the control he thought he did. Jeffries nails the part, especially when he’s being insufferable, but the way Gordon Scott’s Tarzan reacts to him tells us a great deal about the Ape Man as well. It’s understated “anti-chemistry” that gives the film its best character moments.

This was the last Tarzan film for Gordon Scott, and I regretted seeing him go. Scott was too beefy for the role, so the movies limited Tarzan’s acrobatic feats and kept him mostly on the ground using raw muscle power. The few times that Tarzan swings through the trees look clumsy with obvious stuntmen. But even though Scott was better suited physically to the muscleman parts he later played in Italian sword-and-sandal films, his acting skills go above and beyond what might be expected of an actor playing Tarzan in the ‘50s and ‘60s. His Tarzan is hard and no-nonsense, and you wouldn’t want to cross the guy.

The back of the Warner Archive DVD case claims that the final brawl between Tarzan and Coy Banton “in a sense is Tarzan vs. Tarzan.” The reason is that the next actor to take up the Ape Man’s loincloth in the series was… Jock Mahoney. Looking at him as the villain in Tarzan the Magnificent, he seems like an odd choice. Mahoney does a fine job as a smarmy bad guy who is as much a transplant from the Western as John Carradine. Coy Banton has an oily charm that works well to dismantle the heroes and seduce the unhappy Fay Ames. But Mahoney doesn’t look like Tarzan hero material and seems far too old for the part. It turns out that he was: after only doing two movies, Tarzan in India and Tarzan’s Three Challenges, he was removed from the role when Sy Weintraub decided the part needed a younger actor. Mike Henry replaced Mahoney on the next film, the James Bondian Tarzan and the Valley of Gold. Mahoney is a great asset to Tarzan the Magnificent as a villain, but he isn’t one of the great Tarzans.

John Carradine is plenty of fun playing a deranged patriarch with no ounce of empathy for anybody except his sons — or “son,” since he favors Coy over the other two who survive the opening. This isn’t Carradine stretching as a performer — he could play this part in a coma — but if you want John Carradine doing his best John Carradine, here you go.

John Carradine is plenty of fun playing a deranged patriarch with no ounce of empathy for anybody except his sons — or “son,” since he favors Coy over the other two who survive the opening. This isn’t Carradine stretching as a performer — he could play this part in a coma — but if you want John Carradine doing his best John Carradine, here you go.

Al Mulock appears in his second consecutive appearance as a supporting bad guy in a Tarzan film. He gives the most nuanced performance of the Banton clan (no slight against Carradine; I don’t need nuance from him), the only son who starts to doubt the bloody history of the family. Tragically, Mulock committed suicide on the filming location of the best movie he acted in, Once Upon a Time in the West, in 1969. (Mulock was one of the three assassins waiting for the train arrival in the legendary opening scene.)

Producer Sy Weintraub brings on his favorite style of jungle violence: fight dirty! There’s a lot of rolling around in the mud and over sharp rocks with people getting bruised and their clothing shredded. None of it looks like the tidy violence of previous decades where nobody even messed up their hair and suits remained buttoned even after a barrage of Tommy gun fire. There are two moments of violence in the build-up to the climax that have real shock power: a death by close-range rifle shot to the head (owww-uch!) and a killed-by-lions sequence delivered to a character whom you never expected to get this savage a comeuppance. This second kill came as such a surprise the first time I watched the movie that I had to scan back on the disc to double check that… yes, the lions fed tonight.

The showdown between Tarzan and Coy Banton replays much of the action from the end of Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure (including the same location), but the only way it fails to live up to the earlier finale is that it doesn’t hit the last note hard enough. These aren’t two guys fighting; these are beasts hammering each other into submission. It’s the kind of action scene where you start to get concerned about the safety of the actors and the stuntmen. Particularly the actors, since Scott and Mahoney are clearly doing a large percentage of their own stunts. We don’t get to see action scenes this brutal and real often enough, and it’s a shame.

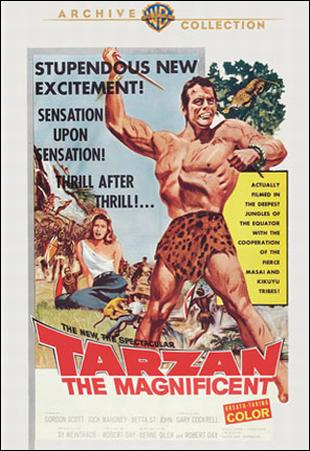

“This Film Was Made in Africa” is the last credit on the opening titles, as if the mention of the co-operation of the Masai and Kikuyu tribes right before that was not enough. (The original poster, on the other hand, offers the backhanded compliment of “the cooperation of the fierce Masai and Kikuyu tribes!” Good ol’ colonial exploitation, huh?) It seems redundant to point out that location filming is an immense aid to the movie, but I recently watch 1998’s Tarzan and the Lost City, which was shot in Africa as well but looks like it might have been made in the San Diego Zoo. Tarzan the Magnificent doesn’t make that mistake, and smoothly blends the handful of studio sets with the outdoor footage. The one exception is the native dance, which also plays under the credits, where the ripples in the “sky” are visible.

“This Film Was Made in Africa” is the last credit on the opening titles, as if the mention of the co-operation of the Masai and Kikuyu tribes right before that was not enough. (The original poster, on the other hand, offers the backhanded compliment of “the cooperation of the fierce Masai and Kikuyu tribes!” Good ol’ colonial exploitation, huh?) It seems redundant to point out that location filming is an immense aid to the movie, but I recently watch 1998’s Tarzan and the Lost City, which was shot in Africa as well but looks like it might have been made in the San Diego Zoo. Tarzan the Magnificent doesn’t make that mistake, and smoothly blends the handful of studio sets with the outdoor footage. The one exception is the native dance, which also plays under the credits, where the ripples in the “sky” are visible.

The presentation of the MOD DVD is adequate: the available print has some damage, although never at distracting levels, and aging has made the colors shift toward red. The original poster reproduced on the DVD cover advertises “BREATH-TAKING COLOR” (Eastman Color by Pathé) but time has taken its toll. The mono sound is excellent, however, which means you can enjoy both the lush jungle soundscape and Ken Jones’s score that plays the same two-note “stalking” motif at every possible moment. As with other Warner Archive discs, there are chapter stops at ten-minute intervals and a menu screen with only the option to play the movie.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

[…] of the earlier “New Look” Tarzan films with Gordon Scott — Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure and Tarzan the Magnificent — yet it manages to move the Ape Man, played by Mike Henry, smoothly into the arena of 1960s […]

[…] Weintraub, an American best known for a series of Tarzan films (you can read Ryan Harvey’s review of one here), paid a large sum of money to the Doyle Estate for rights to all sixty of the original Holmes […]

I enjoyed Tarzan The Magnificent a lot and liked Gordon Scott’s performance. However, I was put off by the fight scene between Tarzan and Bantan. Burroughs’ Tarzan would not have fallen into Coy’s traps, like climbing up a cliff right into a kick, taking several punches to the face without blocking them, etc. They could have evened it out without making Tarzan look stupid. Bantan pulling a knife, pickin up a rock, come to mind, as opposed to a less than Magnificent Tarzan.