Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Or Maybe It Can’t Be Toned Down

I got my first taste of Greek mythology from D’Aulaire’s Greek Myths. Later, when I was old enough for Bulfinch’s Mythology, I thought I had graduated to the real thing. Homer came to me by way of a dusty turn-of-the-century book with a title along the lines of The Boy’s Own Homer, with glorious color illustrations. D’Aulaire gave me the Norse myths, too, though I didn’t get The Ring of the Niebelungen until a friend gave me a mixtape that included Anna Russell’s brilliant twenty-minute Ring cycle sketch.

I got my first taste of Greek mythology from D’Aulaire’s Greek Myths. Later, when I was old enough for Bulfinch’s Mythology, I thought I had graduated to the real thing. Homer came to me by way of a dusty turn-of-the-century book with a title along the lines of The Boy’s Own Homer, with glorious color illustrations. D’Aulaire gave me the Norse myths, too, though I didn’t get The Ring of the Niebelungen until a friend gave me a mixtape that included Anna Russell’s brilliant twenty-minute Ring cycle sketch.

When my parents realized I knew nothing whatever about the Bible — I was ten — they rectified my cultural illiteracy with Pearl Buck’s two-volume The Story Bible. Of all those beginner versions of classics, only Buck’s biblical books kept all the sex and violence in. Imagine my shock when my mother handed me Ovid’s Metamorphoses in Mandelbaum’s complete and very faithful translation. I was twelve. What was she thinking? If the Metamorphoses were a blog, every post would have cut text with PTSD trigger warnings.

Mark Rigney’s post on how old a kid should be before reading or watching The Hunger Games touched on a problem I face often as a teacher of teenagers, some as young as 13. Since I’m a freelance teacher, making house calls, my students’ parents are sometimes directly involved in the question of how old is old enough for which book. Other times, especially when the parents don’t speak much English, I actually wish I could involve them more directly than the language barrier allows.

I’ll face the age question all over again, differently, when my own kids can read on their own. Inevitably, I come at the predicament through my own history as a reader — which stories I was denied too long or permitted too early. As a maker of stories, I’m fascinated also with seeing what of a story can survive the translation into the consciousness of the young, either through the efforts of adult writers who reinterpret the stories, or through the efforts of kids themselves when they try to make sense of them.

Some children’s versions of adult classics become classics in their own right, like Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, which is still the go-to Shakespeare book for elementary-age kids, though it first appeared in print in 1807. Take a look at the classics-for-kids books on offer in your local library or bookstore and ask yourself whether they’re likely to hold their appeal for two centuries.

Some children’s versions of adult classics become classics in their own right, like Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, which is still the go-to Shakespeare book for elementary-age kids, though it first appeared in print in 1807. Take a look at the classics-for-kids books on offer in your local library or bookstore and ask yourself whether they’re likely to hold their appeal for two centuries.

My fancy education trained me to look down my nose at popularizations or bowdlerizations of any kind, but even in my snobbiest moments, I would have to admit that the Lambs have an impressive track record. They do make some weird choices about which things to leave in and which to take out, though. Their version of King Lear discusses the evil sisters’ marital infidelity, but omits the torture of the elder Earl of Gloucester, which is one of the most powerful scenes in the play.

I can see why authors writing for children would hesitate to mention that one of the good guys gets his eyes plucked out. On the other hand, the evil sisters’ infidelity happens off-stage, so that only its consequences play out right in front of a live audience.

I look back on the first time I saw a live production of King Lear–I hadn’t read the play in advance, and nobody had warned me about the eyeball scene. It was a great performance. A really compelling, visceral performance. In case you, too, have never been warned, I don’t think it would be a spoiler to tell you, considering that Lear was first staged in 1606, that the Earl of Gloucester loses his eyes to torture in Act III, scene 7. The Lambs could have performed a great public service by bracing generations of people for that spectacle. The way they decided to protect their readers from having to imagine it too vividly was by eliminating the good Earl of Gloucester almost completely from their tale, while far less important characters (with less visually disturbing fates) stay in the story.

It’s tempting to pass judgment on whether this is a valid way to present Lear to an audience that’s not ready for the real thing. Assuming that Shakespeare is so central to our culture that some adaptation for children is going to be out there for every generation, it might as well be the Lambs’.

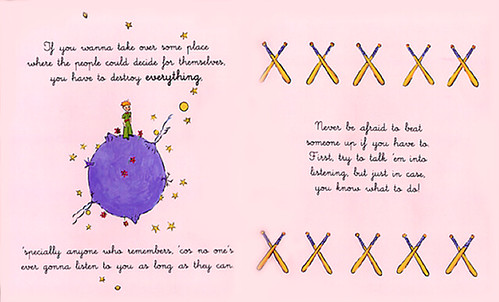

For a text like Lear, adaptation is at once impossible and inevitable. By contrast, Machiavelli’s The Prince turns out to be all too easy to translate into terms children could easily understand. Claudia Hart’s A Child’s Machiavelli: A Primer on Power was clearly not written for real children — it’s a hilarious send-up of adaptations for kids, written for an adult audience.

For a text like Lear, adaptation is at once impossible and inevitable. By contrast, Machiavelli’s The Prince turns out to be all too easy to translate into terms children could easily understand. Claudia Hart’s A Child’s Machiavelli: A Primer on Power was clearly not written for real children — it’s a hilarious send-up of adaptations for kids, written for an adult audience.

What makes Hart’s book work so well as satire is that it really does communicate Machiavelli’s core ideas at a level that a kindergartner could grasp and apply. The book could work on the level of what it appears to be, and for precisely that reason, no responsible adult would ever want a real child to get his or her hands on a copy. In Hart’s illustrations, pastel puppies plot military occupations, and figures from earnest classics of children’s literature appear in apt yet horrifying reconfigurations. After you’ve seen A Child’s Machiavelli, all moral primers for children look at least a little sinister.

In the tradition of fantasy literature, there are plenty of works that probably could be adapted for children, yet probably shouldn’t. H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos has been an irresistible target for parodists. Is it possible to pull off a straightfaced version of any original Lovecraft Cthulhu story, one intended to communicate the moods Lovecraft created, in terms a child could follow? I’m not sure it is. Yet I’ve met elementary-school-aged children who could give a pretty detailed and accurate account of Cthulhu and his lore, gathered mostly from parodies they didn’t quite get. Hollywood merchandising will not spare us Conan for kindergartners, but at least I think we will be spared a kindergarten Silmarillion.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

Just had to comment that D’Aulaires’ Book of Norse Myth along with the Norse section of 1st edition DnD’s Deities and Demigods were huge favorites of mine when I was 11, 12 and 13. I was actually first introduced to Lovecraft, Moorcock and Leiber because of the latter book. Thanks for the post!