Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Battles, Reluctance, and Service to the Sea of Stories

We’ve come to the last installment of my review of Writing Fantasy Heroes: Powerful Advice from the Pros. It’s a peculiar book, different in several ways I have talked about before from other books on writerly craft. It’s specialized by both genre and cluster of techniques, and each chapter shows a noted author using examples from his or her own work to demonstrate how to use a particular technique well (or, in the case of early drafts, badly, followed by advice on revision). Although the book is, by design, most useful for the newcomer to writing fantasy, it has something to offer more seasoned writers, and it’s of great value to teachers of writing who specialize in, or are at least willing to engage with, genre fiction.

Paul Kearney’s piece on large-scale battle scenes is just what I hoped it would be. You know all the familiar gripes about fantasy warfare that fails the suspension-of-disbelief test: the army never seems to eat or excrete, never needs to get paid, charges its horses directly into walls of seasoned enemy pikemen, and so on. “So You Want to Fight a War” addresses all those mundane things an author must get right if the fantasy elements of her story are to feel real to the reader, and then Kearney pushes past the gripes into solutions that any conscientious author can learn to implement. It’s that last bit that I found truly refreshing — many discussions of military verisimilitude get bogged down in griping. Kearney assumes throughout that it’s possible for his reader to get this stuff right, with enough good models, research, and practice.

Paul Kearney’s piece on large-scale battle scenes is just what I hoped it would be. You know all the familiar gripes about fantasy warfare that fails the suspension-of-disbelief test: the army never seems to eat or excrete, never needs to get paid, charges its horses directly into walls of seasoned enemy pikemen, and so on. “So You Want to Fight a War” addresses all those mundane things an author must get right if the fantasy elements of her story are to feel real to the reader, and then Kearney pushes past the gripes into solutions that any conscientious author can learn to implement. It’s that last bit that I found truly refreshing — many discussions of military verisimilitude get bogged down in griping. Kearney assumes throughout that it’s possible for his reader to get this stuff right, with enough good models, research, and practice.

As in Brandon Sanderson’s chapter on “Writing Cinematic Fight Scenes,” the reader is urged to map the combatants’ positions in space. Of course, with at least two armies’ worth of combatants, what one does with the map is a little more complicated this time around:

Keep the map beside you as you write, and as the narrative progresses and the lines move and break and reform, annotate your map. By the end of the battle it should be covered in scrawls, but you will still see the sense within it. It should also have a scale, so that if you want one character to see another across that deadly space, you can gauge whether it’s possible or not. Battlefields can be large places, miles wide. Our ten thousand men, standing in four ranks shoulder to shoulder, will form a line over a mile and a half long, and that’s close-packed heavy infantry such as Greek spearmen or Roman legionaries. If your troops are wild-eyed Celtic types who like a lot of space to swing their swords, it will be even longer.

Okay, that’s a little daunting, but Kearney also offers things like a breakdown of pre-gunpowder tactics into a set of relationships that he likens, persuasively, to rock-paper-scissors. If you can remember how that kindergarten game works, you can avoid some of the biggest beginner blunders in the genre.

Some say there are two kinds of writers: planners and seat-of-the-pantsers. So far, the collection has been heavy on planners, but the pantsers have their say, too. Glen Cook’s “Shit Happens in the Creation of Story, Including Unexpected Deaths, with Ample Digressions and Curious Asides” discusses surprises, both to the reader and to the writer. According to Cook, we all want, definitely in our own lives and to some extent in our stories, for loss and suffering to have meaning, logic, and balance. Alas, shit happens, and if your world is to feel real, shit has to happen in it.

Some say there are two kinds of writers: planners and seat-of-the-pantsers. So far, the collection has been heavy on planners, but the pantsers have their say, too. Glen Cook’s “Shit Happens in the Creation of Story, Including Unexpected Deaths, with Ample Digressions and Curious Asides” discusses surprises, both to the reader and to the writer. According to Cook, we all want, definitely in our own lives and to some extent in our stories, for loss and suffering to have meaning, logic, and balance. Alas, shit happens, and if your world is to feel real, shit has to happen in it.

For writers who work intuitively, connecting with a sort of collective unconscious that Cook calls the Sea of Stories, shit happens in the creative process as well. The Sea of Stories may require that you put things on the page without knowing why at the time, or maybe ever, except that your intuition tells you that your story cannot be told true in any other way. Characters you had plans (and perhaps deep affection) for may die or change suddenly. All kinds of incidents may arise that don’t fit your outline.

In Cook’s experience, these frustrating shifts produce a better story than his conscious mind alone could create. Train your unconscious mind to produce good surprises, and train your conscious mind to accept them. Some die-hard planners will find this advice impossible to connect with–I can say, as a seat-of-the-pants writer whose habit of arguing with my characters has been half-jokingly likened to a dissociative disorder, that writers who fall at the extreme of either mode of production have trouble trying out the other side’s methods. That said, writers whose creative processes don’t fall at an extreme do seem to benefit from trying both sets of techniques. For them, and for new writers who haven’t yet settled into a reliable process, Cook may have something crucial to offer.

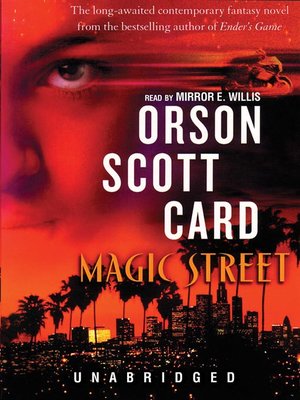

Orson Scott Card, in “The Reluctant Hero,” also urges writers to respect the unconscious mind, though he does so after laying out a useful taxonomy of heroic types: the Hero Who Seeks to be Heroic, the Hero by Career, the Hero of Circumstance, and of course the Reluctant Hero. All of them can be admirable–even the ambitious Homeric hero who seems to modern readers to be overly concerned with Good Fame– and all of them can carry brilliant stories, but according to Card, the Reluctant Hero is the most admirable, and might therefore be able to carry the most powerful stories. Here Card uses a film whose creators failed its hero, abysmally, to illuminate what makes the Reluctant Hero type so powerful, and so difficult to write well:

Orson Scott Card, in “The Reluctant Hero,” also urges writers to respect the unconscious mind, though he does so after laying out a useful taxonomy of heroic types: the Hero Who Seeks to be Heroic, the Hero by Career, the Hero of Circumstance, and of course the Reluctant Hero. All of them can be admirable–even the ambitious Homeric hero who seems to modern readers to be overly concerned with Good Fame– and all of them can carry brilliant stories, but according to Card, the Reluctant Hero is the most admirable, and might therefore be able to carry the most powerful stories. Here Card uses a film whose creators failed its hero, abysmally, to illuminate what makes the Reluctant Hero type so powerful, and so difficult to write well:

I think of the horrible moment in the botched movie The Rock, in which Nicholas Cage has to save San Francisco from a biological death agent. That was his job–he is in the fireman category of hero. But the hackmeisters of Hollywood (either the writers or the executives who defile their work) decided that saving a million people just wasn’t enough jeopardy. So the script has Nicholas Cage’s lover happen to arrive in the danger zone, so now if he fails, she dies.

The audience groaned aloud, not out of empathy but in disgust. The filmmakers, utterly ignorant as they were of how storytelling actually worked, had increased the jeopardy, but at the cost of virtually negating Cage’s heroism. Now instead of risking death to save the community–heroism–he was risking death to save his main squeeze, his primary reproductive opportunity. Now his urgency isn’t noble, it’s practical.

We might call people who save their children or spouses heroes, but we don’t emotionally group them with the heroes who gave or risked their lives for strangers. They are brave, but their motivation is personal, not public. If they failed to act, they would be among the primary sufferers; they are sparing themselves.

The essence of the true reluctant hero is that he is not acting primarily to save himself or those closest to him. He is acting to save a larger community–even the entire human race or the whole world–from a dire threat. He is reluctant to do the heroic deed in part because it is not personal. His own stake in the matter is no more than that of most other people in his community, and yet he must step into a situation that usually offers no plausible escape once he has done the noble deed.

It’s a long excerpt, yes, but having an example of what a botched job looks like is helpful. This passage put me in mind of some writing advice regarding tension that has become popular in recent years: raise the stakes on every page. This tension-centered advice derives in part from Hollywood, coming as it originally does from an agent who favors novels that would translate well into Hollywood movies. No matter how bad you’ve made it for your hero so far, this agent writes, on the next page you need to make it worse and more personal. The writer who follows this advice produces a hero whom Card would describe as the “coy” or “formulaic” reluctant hero, one who declines to serve the greater good until doing so also serves himself. Card would urge us to write better heroes than that.

Where does the unconscious connection to the Sea of Stories come in? Why, right here:

Now that I’ve said all this, what have I accomplished? Is this a formula that you can follow? Oh, I hope not. I hope you will learn the other lesson, that it is what you unconsciously care about and believe in that will make your stories most powerful and truthful. And yet it will not hurt a thing if you are aware of these elements of the Reluctant Hero, as long as you never distort your fiction to achieve them. Tell the story that feels true and important to you, regardless of rules or formulas or mythic patterns or archetypes; they only work when they are unconsciously followed.

In his case, the Reluctant Hero suits best the kind of story he aspires to write–as he puts it, “Noble Romantic Tragedy.” If that’s not your thing, or not your thing for every single project, some other hero type might best suit your story. If you’re working on a manuscript that is, say, a Domestic Comedy of Epistemology with Eruptions of the Otherworld, or a Family Saga of Revolution with Bonus Ancestor Worship and Meddling of the Pesky Dead, you might need something weirder.

Jason M. Waltz’s afterword, though, proposes that fantasy heroes reveal the nature of hero-ness by stripping away the distracting familiarity of our own world to show what survives transposition into some other. That’s what our genres offer that mainstream literature can’t, even when a mainstream author tries in good faith to consider heroism.

Jason M. Waltz’s afterword, though, proposes that fantasy heroes reveal the nature of hero-ness by stripping away the distracting familiarity of our own world to show what survives transposition into some other. That’s what our genres offer that mainstream literature can’t, even when a mainstream author tries in good faith to consider heroism.

Waltz says we need, envy, and depend on our heroes. We share their stories, whether observed or invented, in part because we need there always to be more heroes. We need them to inspire us in case we need to be heroic, and to save us if it is not given us personally to be heroic. Heroes in all kinds of stories matter. Waltz calls on the reader to continue the vital work of creating heroes, for the benefit of all:

Writing Fantasy Heroes gathers the expertise of recognized storytellers; professionals with well known and adored heroes come to share from their wells of knowledge and experience, and provide the tools and attitudes crucial to sharing those heroes. They cannot create for you, though. Only you can bring your heroes. You write their deeds; you deliver their tales to the world. It’s your turn to create our heroes.

And with encouragement like that, the young writer need not be reluctant. Why not be, if only by means of your writing, the Hero Who Seeks to be Heroic, and struggle for Good Fame?

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

Thank you for the great 4-week review Sarah. I appreciated it very much.

I am surprised (and slightly disappointed) that no one has commented on the last two covering the last half of the book. At the very least, I expected some sort of commentary over Cook’s essay title 🙂

Keep up the obviously very well-delivered tutoring and analytical contributions, I look forward to reading them.

It was a pleasure. Do I understand from your comment on Violette’s post that’ you’re planning a sequel? I’d love to see it if/when it comes into being.

Cook’s essay title is a great example of (among other things) the importance of correct punctuation. My brain kept wanting to excise that comma and make the subtitle into “Including Unexpected Deaths with Ample Digressions and Curious Asides.” When eventually I meet my end, if I die as I have lived, my death will surely have ample digressions and curious asides (though I’m hoping to avoid the “unexpected” part).

Probably the reason there weren’t comments on the 3rd and 4th installments is that I didn’t have time to reply to the comments on the 1st and 2nd in the weeks when they went up. Replies breed comments. My bad.

Well, I must have enjoyed the reviews, even if I didn’t comment. I’ve just purchased a copy for my kindle and am looking forward to it 🙂

@ Sarah: Quite right, I’d say I’m headed to a death with ample digressions and curious asides as well! 🙂 As for planning a sequel…yes and no. No, there wasn’t one planned originally; yes, I’d love to do one. Selecting an appropriate follow up is one of the difficulties…I have no desire to do the ‘expected’ WRITING FANTASY VILLAINS. That’s been overdone in my opinion. I’ve discussed alternatives with a few folks, have an idea or two percolating on the back-mind-burner. We’ll see what shakes out. And I’ll definitely keep you informed.

@ peadarog: Thanks mate! I look forward to hearing what you think of it.

[…] recent days, Sarah Avery has been doing some excellent in-depth posts reviewing Writing Fantasy Heroes, a collection of essays from some of the best fantasy practitioners in the […]