Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Revenge of Son of Writing Fantasy Heroes

I’ve been writing about Jason M. Waltz’s Writing Fantasy Heroes: Powerful Advice from the Pros for a couple of weeks now. It’s specialized, far more specialized than most classic how-to-write books, which usually talk about fiction generally, or process generally, or a whole genre at a time. Examining every permutation of a particular technical challenge in a particular genre is a weird thing for a writing book to do. The essays Waltz has assembled here are also structurally similar in an uncommon way: in each essay, the author walks the reader through passages from his or her own work, sometimes in early draft, with comments about choices that worked or didn’t. The how-to-write book is a genre beset by the Problem of Terrible Sameness, but Writing Fantasy Heroes is different from any other writing book on your shelves. While it may not have the universality of John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction, it will help a great many new writers already know how they want to specialize.

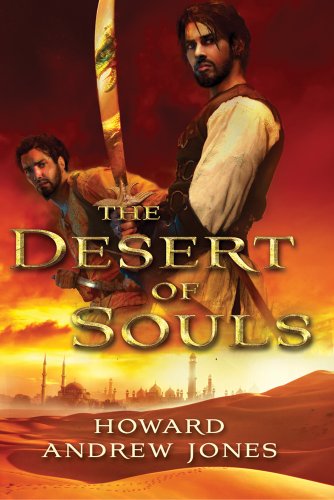

Howard Andrew Jones’s “Two Sought Adventure” details the problems and potentials in stories that have more than one hero. A story with multiple heroes is very different from a one-hero story with a sidekick, love interest, foil, nemesis, or whatever. There are plenty of straightforward techniques for using secondary characters to reveal a single protagonist’s character. Using two (or more) heroes to do this for one another in a way that feels balanced and gratifying for the reader is a tougher trick. Dialogue is crucial, and Jones offers close readings of dialogue from his own work and others’ that illustrate ways to welcome the reader into the shorthand, in-jokes, and shifting tones in conversations between longtime friends. He also addresses a problem I’ve seen in too much professionally published fiction: the duo that bickers like an old married couple, to the point where you wish they would split up, go away, or get eaten by the monster already. Friends have conflict, and friends engaged in epic heroics may have epic conflicts, but bickering is only entertaining in small doses, and it’s rarely illuminating. Jones offers a variety of specific alternative ways to handle conflict between heroes, and to interweave it with a story’s other conflicts.

Howard Andrew Jones’s “Two Sought Adventure” details the problems and potentials in stories that have more than one hero. A story with multiple heroes is very different from a one-hero story with a sidekick, love interest, foil, nemesis, or whatever. There are plenty of straightforward techniques for using secondary characters to reveal a single protagonist’s character. Using two (or more) heroes to do this for one another in a way that feels balanced and gratifying for the reader is a tougher trick. Dialogue is crucial, and Jones offers close readings of dialogue from his own work and others’ that illustrate ways to welcome the reader into the shorthand, in-jokes, and shifting tones in conversations between longtime friends. He also addresses a problem I’ve seen in too much professionally published fiction: the duo that bickers like an old married couple, to the point where you wish they would split up, go away, or get eaten by the monster already. Friends have conflict, and friends engaged in epic heroics may have epic conflicts, but bickering is only entertaining in small doses, and it’s rarely illuminating. Jones offers a variety of specific alternative ways to handle conflict between heroes, and to interweave it with a story’s other conflicts.

In “Monsters–Giving the Devils Their Due,” C.L. Werner covers ground that’s important for beginners, but not so much for writers who are well on their way to the proverbial million words of crap they have to get out of the way before the good stuff kicks in. And that’s okay. Writing a million words takes a long time, so there’s a long window in a writer’s creative development when beginner advice is helpful, sometimes even crucial. Werner warns against giving your hero too easy a victory, because no matter how impressive you say the monster is, if it falls in a single sentence, the reader will find it wimpy, and your hero’s awesomeness will suffer. Lopping heads off the Lernaean hydra should not feel like shooting fish in a barrel. So what do you do to make your monster plausibly intimidating? Among other things, you can develop the monster as deeply as you would a human secondary character, or keep the monster mostly off-stage so that the hero’s conduct with regard to the monster tells us how dire the monster is, or…well, go read Werner. His advice is sound on every point.

In “Monsters–Giving the Devils Their Due,” C.L. Werner covers ground that’s important for beginners, but not so much for writers who are well on their way to the proverbial million words of crap they have to get out of the way before the good stuff kicks in. And that’s okay. Writing a million words takes a long time, so there’s a long window in a writer’s creative development when beginner advice is helpful, sometimes even crucial. Werner warns against giving your hero too easy a victory, because no matter how impressive you say the monster is, if it falls in a single sentence, the reader will find it wimpy, and your hero’s awesomeness will suffer. Lopping heads off the Lernaean hydra should not feel like shooting fish in a barrel. So what do you do to make your monster plausibly intimidating? Among other things, you can develop the monster as deeply as you would a human secondary character, or keep the monster mostly off-stage so that the hero’s conduct with regard to the monster tells us how dire the monster is, or…well, go read Werner. His advice is sound on every point.

Jennifer Brozek assumes and embraces the overlap between fantasy literature and fantasy roleplaying games in “NPCs Are People Too.” As a longtime professional game designer, as well as a writer, she thinks comfortably in the terms of both media. In this book, her approach to minor and walk-on characters makes perfect sense. I imagine a non-gaming writer would find the gaming jargon to be an obstacle, or at best a distraction. (Perhaps someone reading this post is a non-gamer who has read Writing Fantasy Heroes. If so, I’d love to see in comments how this essay played for you.) I’m still on the fence about whether the gaming talk added anything to the content of Brozek’s discussion of minor characters, even for the writer who games. (I speak as a writer worked up her protagonists in GURPS, just to check, after a critique partner said her heroes were “built on too many points.”) Certainly Brozek’s description of her card file of NPCs she generates and keeps around in case she ever needs them sounds like it started as a Game Master’s trick.

Jennifer Brozek assumes and embraces the overlap between fantasy literature and fantasy roleplaying games in “NPCs Are People Too.” As a longtime professional game designer, as well as a writer, she thinks comfortably in the terms of both media. In this book, her approach to minor and walk-on characters makes perfect sense. I imagine a non-gaming writer would find the gaming jargon to be an obstacle, or at best a distraction. (Perhaps someone reading this post is a non-gamer who has read Writing Fantasy Heroes. If so, I’d love to see in comments how this essay played for you.) I’m still on the fence about whether the gaming talk added anything to the content of Brozek’s discussion of minor characters, even for the writer who games. (I speak as a writer worked up her protagonists in GURPS, just to check, after a critique partner said her heroes were “built on too many points.”) Certainly Brozek’s description of her card file of NPCs she generates and keeps around in case she ever needs them sounds like it started as a Game Master’s trick.

What I found most intriguingly counterintuitive in Brozek’s essay is that she actually asks herself more initial questions about her walk-on characters than she does about primary and secondary characters, apparently because the NPCs won’t spend long enough onstage for her to discover much about them organically while she writes them. Her advice might not serve every writer, but it could serve writers comfortable with RPGs very well.

What I found most intriguingly counterintuitive in Brozek’s essay is that she actually asks herself more initial questions about her walk-on characters than she does about primary and secondary characters, apparently because the NPCs won’t spend long enough onstage for her to discover much about them organically while she writes them. Her advice might not serve every writer, but it could serve writers comfortable with RPGs very well.

“Tropes of the Trade,” Ari Marmell’s contribution to the book, discusses the tightrope act we all attempt when we write genre fiction. We’re writing in a tradition, using story elements that mark our work as belonging to a particular genre, and our readers want and need us to use some tropes, somehow, to help them navigate our stories. We need to do something fresh with the tropes we use, or else the story turns trite, and then it’s dead on the page. Yet if we refuse to embrace any tropes at all, pursuing originality for its own sake at any cost, the story dies just as dead. Marmell offers a taxonomy of ways to put the classic fantasy tropes to work, balancing your story’s participation in a genre lineage with your story’s need to do something entirely of its own. Using a classic trope doesn’t have to mean being enslaved by it. Ultimately, says Marmell, genre tropes are like any other tool in the writer’s toolkit, for the writer to decide how and when to use them.

Next week, we’ll reach the end of Writing Fantasy Heroes. Weird as it is to say about a collection of essays, I can’t wait to find out how it ends.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

Me too! I can’t wait to learn how this ends!!

I have been enjoying this weekly analysis of the collection Sarah, and very much appreciate this approach. In this post you made several points I like quite a bit, especially this opener:

“Examining every permutation of a particular technical challenge in a particular genre is a weird thing for a writing book to do. The essays Waltz has assembled here are also structurally similar in an uncommon way: in each essay, the author walks the reader through passages from his or her own work, sometimes in early draft, with comments about choices that worked or didn’t…Writing Fantasy Heroes is different from any other writing book on your shelves.”

Thank you!

[…] recent days Sarah Avery has been doing some excellent in-depth posts reviewing Writing Fantasy Heroes, a collection of essays from some of the best fantasy […]