In 1990, the Walt Disney Company launched a new comics imprint, Disney Comics, to publish titles starring their cartoon characters; they’d previously licensed their characters to other comics companies, but the new imprint represented their own entry into the field. The venture met with some initial success and Disney began to plan further imprints, including one under former DC Comics assistant editor Art Young, which would be called Touchmark and feature creator-owned books for ‘mature readers.’ In this context, that meant something like ‘literary fantasy.’ At the time, DC had a number of books labeled for ‘mature readers’ which had gathered critical attention and good sales — among them, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol and Animal Man, Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer, and Peter Milligan’s Shade the Changing Man. Young brought some of these writers over to the projected Touchmark line. Announced titles included a book written by Morrison with art by Steve Yeowell, Sebastian O, one by Milligan and artist Duncan Fegredo, The Enigma, and J.M. Dematteis and Paul Johnson’s Mercy.

In 1990, the Walt Disney Company launched a new comics imprint, Disney Comics, to publish titles starring their cartoon characters; they’d previously licensed their characters to other comics companies, but the new imprint represented their own entry into the field. The venture met with some initial success and Disney began to plan further imprints, including one under former DC Comics assistant editor Art Young, which would be called Touchmark and feature creator-owned books for ‘mature readers.’ In this context, that meant something like ‘literary fantasy.’ At the time, DC had a number of books labeled for ‘mature readers’ which had gathered critical attention and good sales — among them, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol and Animal Man, Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer, and Peter Milligan’s Shade the Changing Man. Young brought some of these writers over to the projected Touchmark line. Announced titles included a book written by Morrison with art by Steve Yeowell, Sebastian O, one by Milligan and artist Duncan Fegredo, The Enigma, and J.M. Dematteis and Paul Johnson’s Mercy.

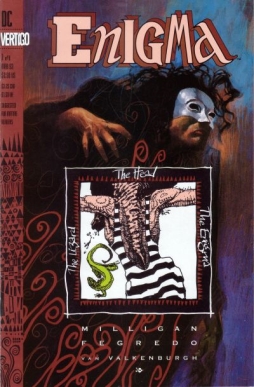

Touchmark never published a book. Sales for the Disney titles had begun to drop, and all the projected imprints were cancelled. But the work wasn’t wasted. Young returned to DC, bringing some of the Touchmark books with him. There, editor Karen Berger was developing a publishing plan for DC’s ‘mature readers’ books, which would be grouped together along with some new titles as an imprint of their own, to be called Vertigo. The Touchmark titles fit in seamlessly, and helped increase the diversity of the new imprint: these weren’t just re-imagined DC characters, but something completely new. I want to write here a bit about one of those books: Milligan and Fegredo’s Enigma.

The Enigma is a difficult book to describe. It opens with a seemingly random sequence of events. A narrator — abrasive, confrontational, but unseen — fills captions with sarcasm and rhetorical questions. Improbable, bizarre things happen; characters react to them in weird, apparently inexplicable ways. But then as the story goes on things begin to link up. What seems deranged becomes coherent. Explanations slowly emerge. Even the identity of the narrator and the reason for that narrator’s tone become clear during the unwinding of the tale. It’s an incredible technical accomplishment that works as more than technique: the surreality breaks open your mind, and the slow-emerging explanations build around peculiar links, feeling like dreams or obsessions, all of it gaining inexplicable depth as it resolves itself into a kind of postmodern Freudian parable. With super-heroes.

…

Read More Read More

It’s tempting to come up with some cheap shot punchline about how tax returns are a subgenre of fantasy literature. I’d poke at the puzzle longer, but I believe in the rule of law, so my tax returns are a good-faith attempt at nonfiction. There are times when I wish I hadn’t been drawn up as a Lawful Good character — goodness knows I tried at least to be Chaotic, but I could never keep it up for long.

It’s tempting to come up with some cheap shot punchline about how tax returns are a subgenre of fantasy literature. I’d poke at the puzzle longer, but I believe in the rule of law, so my tax returns are a good-faith attempt at nonfiction. There are times when I wish I hadn’t been drawn up as a Lawful Good character — goodness knows I tried at least to be Chaotic, but I could never keep it up for long.

In 1990, the Walt Disney Company launched a new comics imprint, Disney Comics, to publish titles starring their cartoon characters; they’d previously licensed their characters to other comics companies, but the new imprint represented their own entry into the field. The venture met with some initial success and Disney began to plan further imprints, including one under former DC Comics assistant editor Art Young, which would be called Touchmark and feature creator-owned books for ‘mature readers.’ In this context, that meant something like ‘literary fantasy.’ At the time, DC had a number of books labeled for ‘mature readers’ which had gathered critical attention and good sales — among them, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol and Animal Man, Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer, and Peter Milligan’s Shade the Changing Man. Young brought some of these writers over to the projected Touchmark line. Announced titles included a book written by Morrison with art by Steve Yeowell, Sebastian O, one by Milligan and artist Duncan Fegredo, The Enigma, and J.M. Dematteis and Paul Johnson’s Mercy.

In 1990, the Walt Disney Company launched a new comics imprint, Disney Comics, to publish titles starring their cartoon characters; they’d previously licensed their characters to other comics companies, but the new imprint represented their own entry into the field. The venture met with some initial success and Disney began to plan further imprints, including one under former DC Comics assistant editor Art Young, which would be called Touchmark and feature creator-owned books for ‘mature readers.’ In this context, that meant something like ‘literary fantasy.’ At the time, DC had a number of books labeled for ‘mature readers’ which had gathered critical attention and good sales — among them, Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol and Animal Man, Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer, and Peter Milligan’s Shade the Changing Man. Young brought some of these writers over to the projected Touchmark line. Announced titles included a book written by Morrison with art by Steve Yeowell, Sebastian O, one by Milligan and artist Duncan Fegredo, The Enigma, and J.M. Dematteis and Paul Johnson’s Mercy.