Teaching and Fantasy Literature: More on Writing Fantasy Heroes

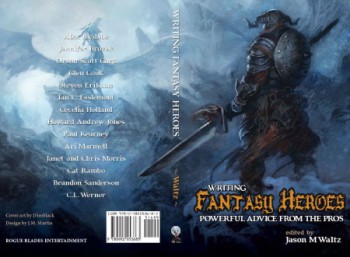

Last week I began a review of Writing Fantasy Heroes: Powerful Advice from the Pros, Jason M. Waltz’s collection of essays on craft. Most of the authors seem to assume the reader is a newcomer to fiction writing, but some of the advice is sufficiently specialized that many veteran writers will also find it useful. It’s also a pleasure to see the authors pull back the curtain on their own work, walking the reader through passages, sometimes in early draft, that illustrate the particular technique or concern of each chapter.

Last week I began a review of Writing Fantasy Heroes: Powerful Advice from the Pros, Jason M. Waltz’s collection of essays on craft. Most of the authors seem to assume the reader is a newcomer to fiction writing, but some of the advice is sufficiently specialized that many veteran writers will also find it useful. It’s also a pleasure to see the authors pull back the curtain on their own work, walking the reader through passages, sometimes in early draft, that illustrate the particular technique or concern of each chapter.

Picking up where we left off last week, we find Ian C. Esslemont coming up with something genuinely new to say about the old adage, “Show, don’t tell.” For the benefit of newer writers, he goes over the familiar territory: why to avoid infodumps, how to recognize them in one’s own drafts, ways to replace them with opportunities for dramatic action, classic blunders like “As you know, Bob” dialogue. Stick with Esslemont to the end, though, despite the groanworthy title of “Taking a Stab at Sword and Sorcery,” and he complicates the choice between showing information and telling it with a third possibility I’ve seen handled in other ways, but never right in a discussion of “Show, don’t tell.”

A writer can also conspicuously withhold information, signaling to the reader that the information will have to be earned, and for seasoned readers of fantasy and science fiction, that kind of puzzle is one of the principal pleasures of reading. This is entirely different from the advice to omit needless information, the stuff you need to research to figure out what goes on the page, but that will only bog down the story and the reader. Esslemont offers some techniques and examples for withholding needed information, and showing rather than telling all the way around the deliberate gap in exposition. It’s a nice piece of work, one that articulated for me some things I’ve been doing that I would have been hard pressed to explain to a student.

Brandon Sanderson’s “Writing Cinematic Fight Scenes” tackles two problems. Firstly, the most obvious way to write fight scenes, with a blow-by-blow account of who hit whom, is probably the worst way, and surprisingly boring. Secondly, writers in our time grow up in a visual culture and derive many of our ideas about what makes an engaging fight scene from film and television, but what works on the screen is usually dead on the page. How do you make a fight scene in a novel or story feel as visually satisfying to the reader as the ones the reader remembers from, say, a Jackie Chan film? The answer is to embrace the things literature can do that film can’t, and to let go of the things film does that literature can’t. Sanderson names and explores the key difference with impressive efficiency and moves on to the three principles a writer needs to have in mind when writing a fight scene: clarity, immersion, and character. (I might add that the same problems and principles probably apply to writing sex scenes. Certainly the boring ones suffer from the same problems that bad fight scenes suffer from. If you’re one of those writers who never look away, no matter what your characters are doing, consider Sanderson’s three principles for the things you keep on the page.)

Brandon Sanderson’s “Writing Cinematic Fight Scenes” tackles two problems. Firstly, the most obvious way to write fight scenes, with a blow-by-blow account of who hit whom, is probably the worst way, and surprisingly boring. Secondly, writers in our time grow up in a visual culture and derive many of our ideas about what makes an engaging fight scene from film and television, but what works on the screen is usually dead on the page. How do you make a fight scene in a novel or story feel as visually satisfying to the reader as the ones the reader remembers from, say, a Jackie Chan film? The answer is to embrace the things literature can do that film can’t, and to let go of the things film does that literature can’t. Sanderson names and explores the key difference with impressive efficiency and moves on to the three principles a writer needs to have in mind when writing a fight scene: clarity, immersion, and character. (I might add that the same problems and principles probably apply to writing sex scenes. Certainly the boring ones suffer from the same problems that bad fight scenes suffer from. If you’re one of those writers who never look away, no matter what your characters are doing, consider Sanderson’s three principles for the things you keep on the page.)

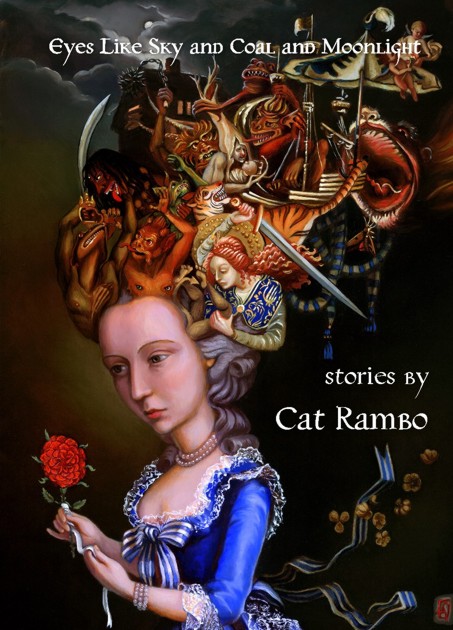

The essay that has pushed back most so far against my training and biases is Cat Rambo’s “Watching from the Sidelines.” She enumerates the advantages to telling a story from the point of view of a character who is not the hero. My training and study as a writer dictates that the main character should be the character who is making most of the choices that matter in a story. Last week I would have said, with some self-satisfaction, that if your character’s choices aren’t the choices driving the plot, you’re writing from the wrong viewpoint. I would have pointed to P.C. Hodgell’s collection, Blood and Ivory, which includes the first story she ever wrote about her signature heroine, Jame. That early story is from the point of view of a bystander who spends a lot of time stunned by the things Jame is willing and able to do. Hodgell’s introduction to that story, “Child of Darkness,” names that decision to write from the bystander’s point as a decision grounded in fear. Having read my way through an anthology slushpile, I can say that fear usually appears to be the reason writers make this choice and it’s rare that I find a writer who can pull it off. James Enge is the notable exception. Most of the episodes in This Crooked Way, for instance, are narrated to glorious effect by secondary characters. Still, I would have described that as one of Enge’s weird superpowers, and might have admonished my students with a stern, “Don’t try this at home, folks.” Cat Rambo demonstrates how difficult it is to write a successful story through a secondary character, but she also demonstrates how to deploy techniques most seasoned writers already have in order to accomplish it. And now I absolutely have to get a copy of her exemplary text, “Eyes like Sky and Coal and Midnight,” because the excerpts she uses for her close readings absolutely kick ass.

The essay that has pushed back most so far against my training and biases is Cat Rambo’s “Watching from the Sidelines.” She enumerates the advantages to telling a story from the point of view of a character who is not the hero. My training and study as a writer dictates that the main character should be the character who is making most of the choices that matter in a story. Last week I would have said, with some self-satisfaction, that if your character’s choices aren’t the choices driving the plot, you’re writing from the wrong viewpoint. I would have pointed to P.C. Hodgell’s collection, Blood and Ivory, which includes the first story she ever wrote about her signature heroine, Jame. That early story is from the point of view of a bystander who spends a lot of time stunned by the things Jame is willing and able to do. Hodgell’s introduction to that story, “Child of Darkness,” names that decision to write from the bystander’s point as a decision grounded in fear. Having read my way through an anthology slushpile, I can say that fear usually appears to be the reason writers make this choice and it’s rare that I find a writer who can pull it off. James Enge is the notable exception. Most of the episodes in This Crooked Way, for instance, are narrated to glorious effect by secondary characters. Still, I would have described that as one of Enge’s weird superpowers, and might have admonished my students with a stern, “Don’t try this at home, folks.” Cat Rambo demonstrates how difficult it is to write a successful story through a secondary character, but she also demonstrates how to deploy techniques most seasoned writers already have in order to accomplish it. And now I absolutely have to get a copy of her exemplary text, “Eyes like Sky and Coal and Midnight,” because the excerpts she uses for her close readings absolutely kick ass.

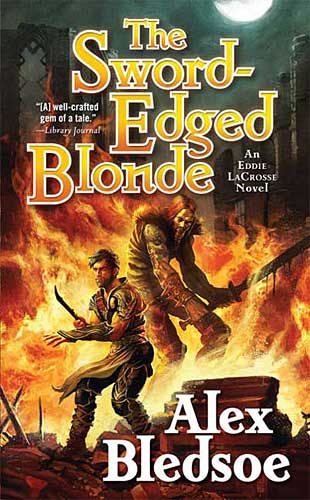

One of the complaints that readers allergic to fantasy raise against the genre is that it’s all coming of age stories about farmboys who turn out to be the rightful heir denied to some kingdom. And that makes up a greater proportion of the genre than any of us are happy to admit, or to read. We’d like a break from Joseph Campbell’s Journey of the Hero, too. Alex Bledsoe, in “Man Up: Making Your Hero an Adult,” takes several kinds of conflicts fantasy heroes are likely to face, and shows how differently those conflicts play out with a young hero just coming of age and with a veteran hero with established skills, habits, and regrets. This chapter is especially useful for a writer of fantasy, more broadly defined, who wants to tackle the sword and sorcery subgenre, which tends to be grittier and less idealistic than the mainstream of the genre. A writer over the age of, say, 30, and who already has strong characterization chops, may not need this chapter. Any writer who could reasonably be described as a youth would probably benefit from this chapter, no matter how good his or her chops, as would a writer new to writing for publication, regardless of age.

One of the complaints that readers allergic to fantasy raise against the genre is that it’s all coming of age stories about farmboys who turn out to be the rightful heir denied to some kingdom. And that makes up a greater proportion of the genre than any of us are happy to admit, or to read. We’d like a break from Joseph Campbell’s Journey of the Hero, too. Alex Bledsoe, in “Man Up: Making Your Hero an Adult,” takes several kinds of conflicts fantasy heroes are likely to face, and shows how differently those conflicts play out with a young hero just coming of age and with a veteran hero with established skills, habits, and regrets. This chapter is especially useful for a writer of fantasy, more broadly defined, who wants to tackle the sword and sorcery subgenre, which tends to be grittier and less idealistic than the mainstream of the genre. A writer over the age of, say, 30, and who already has strong characterization chops, may not need this chapter. Any writer who could reasonably be described as a youth would probably benefit from this chapter, no matter how good his or her chops, as would a writer new to writing for publication, regardless of age.

That’s plenty for tonight. Next week, I’ll begin with Howard Andrew Jones’s “Two Sought Adventure.” If you want to write the heroic fantasy equivalent of a buddy movie, Jones has the brain you want to pick. Meanwhile, if you haven’t already taken a look at John O’Neill’s post collecting Black Gate readers’ definitions of what makes a hero, check it out.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

It surprised me that you react so strongly against the idea of writing from the viewpoint of a character other than the ostensible ‘hero’ of a story. I may be eccentric in this, and sure, sometimes the hero-figure is the right POV. But it seems to me sometimes one wants to see the hero from outside (just ask John H. Watson), and sometimes (many times?) the heroic action really isn’t the point. I dunno, maybe this varies with what you mean by ‘hero.’ Is Ahab or Ishmael the hero of Moby-Dick?

[…] about Jason M. Waltz’s Writing Fantasy Heroes: Powerful Advice from the Pros for a couple of weeks now. It’s specialized, far more specialized than most classic how-to-write books, which […]

[…] recent days Sarah Avery has been doing some excellent in-depth posts reviewing Writing Fantasy Heroes, a collection of essays from some of the best fantasy […]

[…] Teaching and Fantasy Literature: More on Writing Fantasy Heroes […]

[…] You’ll have read some classic set-pieces, and some classic blunders. You may even have read this post, which discusses the biggest pitfall most writers face when they set out to learn how to write a […]