To Unbuild the Unreal City: M. John Harrison’s Viriconium

The term ‘dying earth’ comes from a series of stories by Jack Vance, but Vance was following in the footsteps of Clark Ashton Smith, whose Zothique stories introduced the concept: a setting at the end of time, during the twilight of civilisation on earth — when magic and science had become fused and indistinguishable, when the ruins of previous cultures choked the land, when we and our children and our children’s children are not even memories. Among other writers to tackle similar settings are Michael Moorcock, in his Dancers at the End of Time series, and Gene Wolfe in his classic Book of the New Sun. Wikipedia suggests a few more examples, such as C.J. Cherryh’s Sunfall. Dying-earth stories are typically autumnal, often ironic or cynical, stories about things running down in the senility of the world; often written in a self-consciously baroque style. And, I find, often very powerful works. I want to write a bit here about one of the odder works of an inherently odd subgenre: M. John Harrison’s Viriconium sequence.

The term ‘dying earth’ comes from a series of stories by Jack Vance, but Vance was following in the footsteps of Clark Ashton Smith, whose Zothique stories introduced the concept: a setting at the end of time, during the twilight of civilisation on earth — when magic and science had become fused and indistinguishable, when the ruins of previous cultures choked the land, when we and our children and our children’s children are not even memories. Among other writers to tackle similar settings are Michael Moorcock, in his Dancers at the End of Time series, and Gene Wolfe in his classic Book of the New Sun. Wikipedia suggests a few more examples, such as C.J. Cherryh’s Sunfall. Dying-earth stories are typically autumnal, often ironic or cynical, stories about things running down in the senility of the world; often written in a self-consciously baroque style. And, I find, often very powerful works. I want to write a bit here about one of the odder works of an inherently odd subgenre: M. John Harrison’s Viriconium sequence.

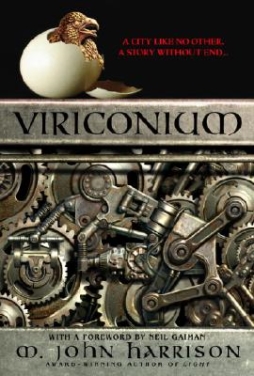

There are four Viriconium books, three novels and a collection of linked short stories: The Pastel City, published in 1971; A Storm of Wings, from 1980; In Viriconium, from 1982; and 1985’s Viriconium Nights. One can technically read the books in any order, as few plot strands directly connect them. They’re bound by setting, theme, and imagery, and to that extent perhaps are best read in order of publication, so that one follows the growth of Harrison’s conception of the books and of his technical facility. At any rate, the internal chronology of the series is intentionally difficult. Omnibus editions treat the short stories of Viriconium Nights in different ways, sometimes putting them together in one place as they would have first appeared, sometimes scattering them before, between, and after the three novels. Harrison has apparently said that the stories can appear in any order, so long as the short story “A Young Man’s Journey to Viriconium” comes at the end.

The four books are very different works, as one might expect from pieces written over 15 years. The style varies radically. So does the tone; the writing, ironic from the start, produces increasingly complex effects. Thematically, key concerns persist, about art and heroism and ritual. And reality; and the way in which fantasies attempt to mimic reality, and the ways in which bad fantasies — or bad fiction — deviates from emotional truth. So these are books that use the form of fantasy fiction to critique, or question, fantasy. Depending on what set of definitions you care to use, you could call this a modernist or postmodernist approach. The more important question is this: does the work succeed as written art?