Tarzan and the Valley of Gold, Part 1: The Movie

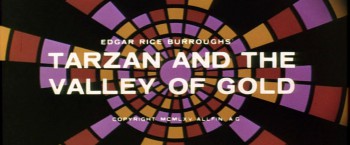

Tarzan and the Valley of Gold wastes no time telling viewers of the mid-1960s that this was not going to be their grandfather’s Tarzan. Or their father’s either. With swinging ‘60s big band jazz backed with bongos playing over a Warholian montage of pop art colors projecting scenes from the movie, it’s impossible not to think JAMES BOND! JAMES BOND! from the moment the opening titles start.

Tarzan and the Valley of Gold wastes no time telling viewers of the mid-1960s that this was not going to be their grandfather’s Tarzan. Or their father’s either. With swinging ‘60s big band jazz backed with bongos playing over a Warholian montage of pop art colors projecting scenes from the movie, it’s impossible not to think JAMES BOND! JAMES BOND! from the moment the opening titles start.

No doubt that was producer Sy Weintraub’s intention with this 1966 outing for Tarzan, the first of a trio starring Mike Henry. The credits sequence is a dead-on imitation of the style of Maurice Binder for Dr. No. After the director’s credit fades, the film hops into a Goldfinger-inspired sweep over a tropical resort city, concluding on a helicopter taking off from a luxury yacht in the harbor. Then, in another scene swiped from Dr. No, assassins shoot a limo driver outside the airport, and an imposter chauffeur awaits the arrival of our handsome hero in his impeccable suit and tie. Cue city montage with more swingin’ Latin big band rhythms! Smash into an action scene where a sunglass-wearing sniper tries to pick off our sharply dressed hero in an empty bullring. The crafty Ape Man turns the tables on the gunman and kills him by dropping a giant Coke Bottle advertising prop onto him. Ah, good times.

Sy Weintraub shows with this opening that he has taken the “New Look” Tarzan he introduced in 1959 in Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure one step further to imitate the stratospheric popularity of spy cinema of the decade. Tarzan not only speaks in complete sentences, but he is comfortable donning civilization’s trappings to travel the world to bring savage ape justice to turtleneck-wearing supervillains who adore exploding watches.

The temptation to go this direction must have been hard to resist: by the start of 1966, Bond-mania was approaching its delirious apex; Thunderball came out in December 1965 and was on its way to becoming one of the highest-grossing movies in history. Bandwagon films are often poor quality imitations, but Sy Weintraub already had a famous character available who could cut a dashing a dangerous figure to put at the center of his attempt to grab some Bond cash. It turned out well, better than you might initially think a “Tarzan goes ’60s spy” film would. Tarzan and the Valley of Gold, currently available as a manufacture-on-demand DVD from Warner Archive, lacks the excellent script, performances, and drama of Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure, but it delivers in the breezy fun department.

Giving Tarzan a 007 makeover is not the betrayal of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s character that it may sound like on the surface. It’s surprising how well the tastes in 1960s adventure merged with an accurate version of the literary Tarzan of the ‘teens and ‘20s. Tarzan was familiar with civilization at the end of the novel Tarzan of the Apes, and was having globetrotting adventures in the next book, The Return of Tarzan. Tarzan and the Valley of Gold does not force the Ape Man to remain in a suit and tie long past the opening scenes: when he sets out to track the missing child Ramel (Manuel Padilla Jr.), whom the villain Augustus Vinero (David Opatoshu) is using the locate the Valley of Tucumai and its corridors stuffed with golden loot, Tarzan sheds the trappings of the city in exchange for a knife, a rope, a loincloth, and some animal sidekicks. The James Bond vibe continues, but it rests with the bad guys and the groovy soundtrack (composed by Van Alexander) from then on.

Giving Tarzan a 007 makeover is not the betrayal of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s character that it may sound like on the surface. It’s surprising how well the tastes in 1960s adventure merged with an accurate version of the literary Tarzan of the ‘teens and ‘20s. Tarzan was familiar with civilization at the end of the novel Tarzan of the Apes, and was having globetrotting adventures in the next book, The Return of Tarzan. Tarzan and the Valley of Gold does not force the Ape Man to remain in a suit and tie long past the opening scenes: when he sets out to track the missing child Ramel (Manuel Padilla Jr.), whom the villain Augustus Vinero (David Opatoshu) is using the locate the Valley of Tucumai and its corridors stuffed with golden loot, Tarzan sheds the trappings of the city in exchange for a knife, a rope, a loincloth, and some animal sidekicks. The James Bond vibe continues, but it rests with the bad guys and the groovy soundtrack (composed by Van Alexander) from then on.

Finding an excuse to get Tarzan (never referred to as John Clayton in the movie) to Mexico is a bit wobbly, but once the villains kidnap the boy Ramel and kill Tarzan’s friend Ruiz (Frank Brandstetter), the movie has a straight line to walk the rest of the way. To make Mexico a more comfortable setting for Tarzan, Ruiz’s ranch provides a few imported African animals that would otherwise have no business wandering around Central America: “Major,” a lion, and “Dinky,” a chimpanzee, both of whom make up Tarzan’s crack squadron. A local beast, the jaguar “Bianco” (“Xima” in the novelization) serves as Tarzan’s advanced scout, since the big cat knows Ramel’s scent. Tarzan and his animal entourage enter the jungle on the trail of the kidnapped boy, while Vinero moves a small army, complete with an M3 Stuart light tank and a Bell 47 helicopter, toward the hidden valley. Tarzan goes up against Vinero’s modern military machines and acquits himself in super Ape Man style. He even gets to command the tank in the showdown in Tucumai.

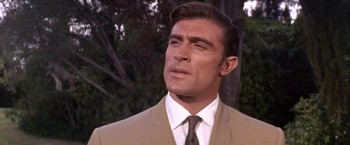

This is the first of the three Tarzan films shot back-to-back in 1965 with Mike Henry in the title role. Henry was a linebacker for the Steelers and the Rams before his movie career, which also included parts in The Green Berets, The Longest Yard, and Smokey and the Bandit. He’s nothing much to shout about in the acting department — far flatter and more wooden than Gordon Scott — but he’s one of the best physical matches for Tarzan in the character’s silver screen history: dark haired, handsome, with the lean physique that makes him appear capable of the acrobatic feats of the Lord of the Jungle. Henry bears a resemblance to Sean Connery, which probably contributed to him getting cast in the first place. In the city-based scenes during the opening, Henry is dressed in a tropical suit that’s an almost perfect match to Sean Connery’s wardrobe in Jamaica in Dr. No. Mike Henry never does anything memorable with his dialogue scenes, although he has decent chemistry with the amateurish performance of young Manuel Padilla; but this is the rare Tarzan actor who looks at home both in the rainforest and in well-tailored suits. Burroughs would have approved.

This is the first of the three Tarzan films shot back-to-back in 1965 with Mike Henry in the title role. Henry was a linebacker for the Steelers and the Rams before his movie career, which also included parts in The Green Berets, The Longest Yard, and Smokey and the Bandit. He’s nothing much to shout about in the acting department — far flatter and more wooden than Gordon Scott — but he’s one of the best physical matches for Tarzan in the character’s silver screen history: dark haired, handsome, with the lean physique that makes him appear capable of the acrobatic feats of the Lord of the Jungle. Henry bears a resemblance to Sean Connery, which probably contributed to him getting cast in the first place. In the city-based scenes during the opening, Henry is dressed in a tropical suit that’s an almost perfect match to Sean Connery’s wardrobe in Jamaica in Dr. No. Mike Henry never does anything memorable with his dialogue scenes, although he has decent chemistry with the amateurish performance of young Manuel Padilla; but this is the rare Tarzan actor who looks at home both in the rainforest and in well-tailored suits. Burroughs would have approved.

Augustus Vinero is an international villain in the Ian Fleming-mold: Finely coiffed with a trimmed beard, dressed in sharp blazers over turtlenecks, headquartered inside an Old World mansion, and accompanied by a muscular henchman (Don Megowan as “Mr. Train”). In his first appearance, Vinero executes an old standby from the supervillain playbook and kills one of his hired hands for insubordination with an elaborate gimmick: in this case, an exploding cigarette trick. (The huge blast also takes out all of Vinero’s swank study, but perhaps he was planning to remodel.) Vinero also likes sending exploding watches to people who displease him, and hangs a nitro-laced necklace off the neck of his mistress, Sophia Renault (Nancy Kovack). Actor David Opatoshu has the right suave look for Vinero, although never gets him near the level of menace of a classic Bond villain.

Augustus Vinero is an international villain in the Ian Fleming-mold: Finely coiffed with a trimmed beard, dressed in sharp blazers over turtlenecks, headquartered inside an Old World mansion, and accompanied by a muscular henchman (Don Megowan as “Mr. Train”). In his first appearance, Vinero executes an old standby from the supervillain playbook and kills one of his hired hands for insubordination with an elaborate gimmick: in this case, an exploding cigarette trick. (The huge blast also takes out all of Vinero’s swank study, but perhaps he was planning to remodel.) Vinero also likes sending exploding watches to people who displease him, and hangs a nitro-laced necklace off the neck of his mistress, Sophia Renault (Nancy Kovack). Actor David Opatoshu has the right suave look for Vinero, although never gets him near the level of menace of a classic Bond villain.

The idea of having Nancy Kovack, one of the stars of Jason and the Argonauts, as the heroine in a Tarzan film is spectacular. Kovack plays Sophia Renault, Vinero’s mistress, a part she got cast in at the last moment when Sharon Tate was unavailable. Unfortunately, the film underuses Kovack and she does little aside from run into Tarzan in the jungle, where he detaches the nitroglycerin necklace from around her neck, and then accompany the Ape Man to Tucumai where she sits out the finale doing… I have no idea. She simply vanishes until the coda. There also seems to be a scene missing where she decides to abandon Vinero; the movie has her receiving the explosive necklace from him in one scene, and then a few minutes later she’s running free in the middle of the jungle, begging for help. (Once again, there’s no mention of Tarzan’s wife Jane Porter, but Tarzan and Sophia never get father than bonding over exploding jewelry anyway.)

The idea of having Nancy Kovack, one of the stars of Jason and the Argonauts, as the heroine in a Tarzan film is spectacular. Kovack plays Sophia Renault, Vinero’s mistress, a part she got cast in at the last moment when Sharon Tate was unavailable. Unfortunately, the film underuses Kovack and she does little aside from run into Tarzan in the jungle, where he detaches the nitroglycerin necklace from around her neck, and then accompany the Ape Man to Tucumai where she sits out the finale doing… I have no idea. She simply vanishes until the coda. There also seems to be a scene missing where she decides to abandon Vinero; the movie has her receiving the explosive necklace from him in one scene, and then a few minutes later she’s running free in the middle of the jungle, begging for help. (Once again, there’s no mention of Tarzan’s wife Jane Porter, but Tarzan and Sophia never get father than bonding over exploding jewelry anyway.)

The film’s momentum slows down once the story reaches the valley of the title. The residents of Tucumai are staunch pacifists, leading to overlong scenes of Tarzan telling them they have to resist Vinero and his forces when they arrive, followed by the leader of Tucumai, the elderly Manco, insisting that they have no need of such barbarous actions, etc. But in an odd wrap-up, the people of Tucumai learn the moral lesson that sometimes violence is a good thing! Manco even selects a sadistic, if perfectly ironic, way of dealing with the greedy Vinero when the criminal enters the treasure chamber of the great pyramid. Oh well, if these peaceful folks didn’t get on board the violence train for at least a few stops, the movie would have had no action for the ending.

(Manco is played by Francisco Riqueiro, but is obviously dubbed by Paul “Ghost Host” Frees. Not that I have a problem with this; Paul Frees is welcome to dub anything he chooses.)

(Manco is played by Francisco Riqueiro, but is obviously dubbed by Paul “Ghost Host” Frees. Not that I have a problem with this; Paul Frees is welcome to dub anything he chooses.)

The most overt 007 reference in the film comes during an action sequence where Tarzan downs a helicopter using jerry-rigged bolo-grenades. After the explosion, Tarzan barks into Vinero’s radio: “One of your aircraft is missing.” Thanks, From Russia With Love! And I believe Bond said that after, uhm, downing a helicopter. However, there’s at least one sequence where it appears that Tarzan and the Valley of Gold was the victim of theft: the action set-piece where Tarzan hunts down Vinero’s men inside a natural cave, picking them off with stealth attacks, looks exactly like the Afghan cave fight from Rambo III.

Unfortunately, the helicopter attack shows the relative poverty of the film’s budget; the craft can’t explode on screen since that would require either blowing up a real helicopter or having to mock-up a model, so instead the craft comes to rest behind a bush and then explodes, inexpensively out of sight of the camera. Some of the other action scenes suffer from the low budget; Tarzan’s stand-off with Mr. Train in the climax is weakly choreographed and sometimes relies on jerky under-cranked footage.

Sy Weintraub’s “New Look” Tarzan movies depended on location shooting to add realism and flavor. Tarzan and the Valley of Gold was filmed entirely in Mexico, shooting around Mexico City, Acapulco, Chapultepec Castle (Vinero’s headquarters), and most impressively Teotihuacan. The movie concludes in a classic “Lost Civilization” that will seem to contemporary viewers as Indiana Jones territory. But it comes straight from Burroughs’s typewriter: Tarzan ran into lost cities over and over again. The Valley of Tucumai was photographed at Teotihuacan, the astonishing Mesoamerican ruins thirty miles outside of Mexico City. The expansive physical location helps to offset the narrow budget that crops up elsewhere.

Sy Weintraub’s “New Look” Tarzan movies depended on location shooting to add realism and flavor. Tarzan and the Valley of Gold was filmed entirely in Mexico, shooting around Mexico City, Acapulco, Chapultepec Castle (Vinero’s headquarters), and most impressively Teotihuacan. The movie concludes in a classic “Lost Civilization” that will seem to contemporary viewers as Indiana Jones territory. But it comes straight from Burroughs’s typewriter: Tarzan ran into lost cities over and over again. The Valley of Tucumai was photographed at Teotihuacan, the astonishing Mesoamerican ruins thirty miles outside of Mexico City. The expansive physical location helps to offset the narrow budget that crops up elsewhere.

The one place where Tarzan and the Valley of Gold excels over Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure is in the animal action. The chimpanzee “Dinky” and the lion “Major” (inspired by Jab-Bal-Ja from the novel Tarzan and the Golden Lion) are continual presences, interacting easily with the humans. The leopard Bianco appears extensively in the first third of the movie as well. Few Tarzan films have done such a fine job of showing the Ape Man’s ease with jungle creatures as this one, and the training of the beasts results in astonishingly fluid work with the actors. (Unfortunately, Mike Henry had a nasty encounter with the chimpanzee while filming his second movie, Tarzan and the Great River, causing a serious injury that later led him to sue the producers for unsafe working conditions. This resulted in Ron Ely getting cast for the subsequent television series.)

English Director Robert Day (who, as of this writing, is still with us at age ninety) already had experience with Tarzan: he directed Gordon Scott in his last film, Tarzan the Magnificent, and the second of the two films starring Jock Mahoney, Tarzan’s Three Challenges. He directs with a sure hand for the adventure material, although otherwise feels invisible; the animal trainers probably had as much a say on the film as he did. Robert Day did one more Tarzan film after this, Tarzan and the Great River.

English Director Robert Day (who, as of this writing, is still with us at age ninety) already had experience with Tarzan: he directed Gordon Scott in his last film, Tarzan the Magnificent, and the second of the two films starring Jock Mahoney, Tarzan’s Three Challenges. He directs with a sure hand for the adventure material, although otherwise feels invisible; the animal trainers probably had as much a say on the film as he did. Robert Day did one more Tarzan film after this, Tarzan and the Great River.

The Warner Archive MOD DVD presents the film in its original 2.4:1 Panavision, enhanced for widescreen televisions, with a decent 1.0 mono soundtrack. The print of the film contains damage and some murky colors in a number of scenes, particularly those in Tucumai (although this may be a source issue) but is always watchable. There’s even a bonus feature, the first I’ve seen on a Warner Archive disc: the original trailer.

This is only Part 1 of my look at Tarzan and the Valley of Gold. The topic merits a second installment because of the novelization released to tie-in with the film. Most novelizations aren’t worth discussion, but this one was written by a fellow named Fritz Leiber. Anything with Leiber’s name is worth discussing.

Ryan Harvey is a veteran blogger for Black Gate and an award-winning science-fiction and fantasy author who knows Godzilla personally. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his story “The Sorrowless Thief” appears in Black Gate online fiction. Both take place in his science fantasy world of Ahn-Tarqa. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, the prologue to the upcoming novel Turn Over the Moon, is currently available as an e-book. You can keep up with him at his website, www.RyanHarveyWriter.com, and follow him on Twitter.

I think I’ll have to check out this and Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure, even though they may not be great films. Definitely, Mike Henry is incredibly flat as an “actor” but the concepts sound like fun. Looking forward to your Leiber book review. May have to read that book.

Weintraub features in my favorite “now that’s a case of not doing your homework” story. Circa 1979, he paid a BUNDLE of money to the Arthur Conan Doyle Estate for rights to all 60 of the original stories. He was going to make a series (the number varies, but I’m guessing between 12 and 20) of tv movies for the UK and US. Ian Richardson was cast as the great detective.

As he was filming the second film (the Hound of the Baskervilles, which ahd been preceded by The Sign of the Four) the ground fell out from underneath Weibtraub.

The copyright on all of Doyle’s originals expired in the UK in 1980. Weintraub had no idea. Granada Productions did, however, and they had put in motion a series, to be distributed in the UK and US, to star Jeremy Brett as Holmes. Weintraub freaked out and in conjunction with the Doyle Estate, filed suit against Granada.

The Granada production was put on hold for two years (which allowed them to continue preparations, resulting in a stronger series) until an out of court settlement was reached. Weintraub recovered all his costs plus a tidy profit, so he shut down his franchise.

Richardson is a very underappreciated Holmes (one of my favorites) and the two movies were not bad. Brett’s series set the standard and his popularity in the role rivals that of Basil Rathbone’s.

Richardson (best known in America for the “Do you have any gray poupon?” commercial), missed out on the role of the Emperor in ‘Amadeus’ because Weintraub wouldn’t let him go while the legal wrangling went on.

Richardson did go on to play Dr. Joseph Bell (whom Holmes was largely based on) in the BBC series, Murder Rooms.

How Weintraub had no clue that the stories were about to be available free of charge astounds me for a veteran of the business.

Ah, yes, the giant Coke bottle scene. Product placement that hits the spot. Oh, wait a minute. That was Pepsi.

[…] the part needed a younger actor. Mike Henry replaced Mahoney on the next film, the James Bondian Tarzan and the Valley of Gold. Mahoney is a great asset to Tarzan the Magnificent as a villain, but he isn’t one of the great […]

[…] before reading Leiber’s Tarzan and the Valley of Gold, I needed to see the movie Tarzan and the Valley of Gold. It is, after all, the source material. The original. I needed to play […]