Teaching and Fantasy Literature: So I Guess It’s My Blind Spot, Too

Last week I wrote about trying to understand sports writing as if it were a subgenre of sword and sorcery. For my students’ sakes, I’ll read just about anything–and usually when my students entice or implore me to leave my comfort zone as a reader, something good happens.

I said something myopic last week, and I’m actually glad to have said it here, where it drew thoughtful, friendly responses that have not only helped me get further into my students’ favorite reading, but have also helped me understand what it is about genre fiction that turns off some litfic-only readers. I said:

And what monster does the athlete vanquish in most sporting events?No monster, just a fellow athlete. What threat does the fellow athlete pose, to anybody other than the athlete we’re reading about? In most cases, none at all. In a boxing match, two potentially decent guys beat the snot out of each other, with nothing at stake that truly matters. In a football game, dozens of young men bludgeon their brains against the insides of their skulls, and for what? For bragging rights and cash? How much patience would I have for a fictional character who did as much harm for something as trivial? The more a sport resembles sword and sorcery combat in its results, the less interested I am in it. Conflict will only get you so far when the motives are shallow. Am I a prig? Maybe I’m being a prig.

Nobody said, Yes, Sarah, you’re being a prig. So, um, thank you for your patience and forbearance.

What happened instead was a conversation about conflict and its stakes generally, a conversation I’ve continued having with myself all week.

What’s cosmically at stake in the kinetic energy transaction between a ball and a bat? Nothing. What was at stake when Jackie Robinson integrated major league baseball?

I’d always held it against athletic endeavors that they were only interesting as the backdrop or MacGuffin for something else, something that actually did possess intrinsic value–national dignity, personal redemption, uplift from poverty, that sort of thing. If, as in Slumdog Millionaire, the place of the big game can be filled by a quiz show, isn’t that an indictment of the big game per se?

On further reflection, no, it’s not. Because the same thing is true of more universally human behaviors like violence or sex. (Don’t think violence is universal? Spend some time with toddlers. They all hit, and push, and worse. When you were three years old, you hit, too. I would bet five dollars that His Holiness the Dalai Lama was a hitter at age three. Probably also a biter.)

It seems I thought about sport the way most English teachers talk about violence. Ralph Fletcher, in Boy Writers: Reclaiming Their Voices (a book I’ve mentioned at Black Gate before), puts it this way:

It seems I thought about sport the way most English teachers talk about violence. Ralph Fletcher, in Boy Writers: Reclaiming Their Voices (a book I’ve mentioned at Black Gate before), puts it this way:

Consciously or unconsciously, we may fall into the habit of using language that is charged and negative when talking with colleagues about writers and their writing. For instance, I often hear teachers say that they don’t want boys to glorify violence. [G]lorify is a “ramp-up” word. Boys don’t use violence or include violence or experiment with violence in their stories–they glorify violence. That verb pushes violence up another notch or two to emphasize just how unpleasant it is.

Many of us may use ramp-up words or expressions without being aware of it. For example, some teachers told me they don’t like it when boys put “gratuitous violence” in their stories.

“Interesting that we never talk about ‘gratuitous dialogue,'” observes Peter Johnston.

…Words and phrases like these contain an implicit judgment–the kid is guilty simply by the words we use to describe the writing.

I can read with appreciation of technique (both martial and literary) almost all of the gritty scenes in George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, but grimace involuntarily at films I might otherwise enjoy because they include gratuitous sports scenes. The Blind Side almost got me into the theater, but I can’t stand to see football glorified.

Weirdly, the more sympathetic I become with my students’ reading tastes, the more sympathetic I also become with the distaste mainstream critics experience when they consider the books I love. If “gratuitous” is just a mistranslation of “I didn’t like it,” and “glorify” is just a mistranslation of “I disapprove of it,” then we’re down to plain old diversity of tastes, and if even I can chip away at my snobbery, who’s to say what snob can’t?

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

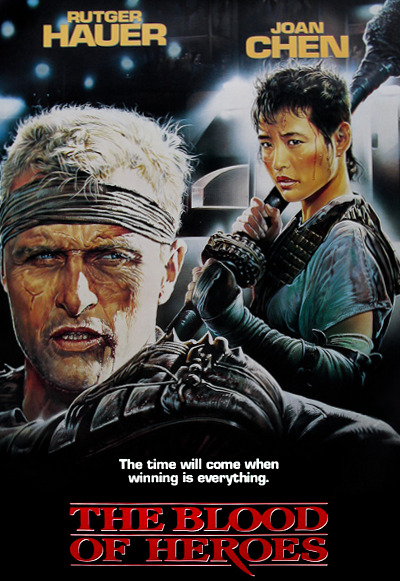

No comment on the verbiage, but I just wanted to comment on Blood of Heroes.

“I’ve broken Juggers in half, smashed their bones, left the ground behind me wet with brains. There’s nothing I wouldn’t do to win. But I never hurt anyone for any reason other than sticking a dog’s skull on a stake.”

Surprisingly good movie.