Teresa Edgerton’s Goblin Moon

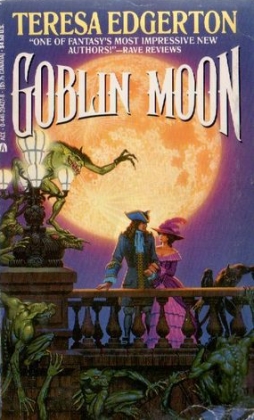

I’ve mentioned before that I’ve an idea that there’s a lot to be learned from some of the overlooked fantasies of the 1980s. Teresa Edgerton’s Goblin Moon was published in 1991, and it’s less obscure than some — in fact, it’s just come out as an ebook (you can find a trailer here) — but it’s still a good example of what I have in mind. And a fine and delightful tale in its own right.

I’ve mentioned before that I’ve an idea that there’s a lot to be learned from some of the overlooked fantasies of the 1980s. Teresa Edgerton’s Goblin Moon was published in 1991, and it’s less obscure than some — in fact, it’s just come out as an ebook (you can find a trailer here) — but it’s still a good example of what I have in mind. And a fine and delightful tale in its own right.

Goblin Moon is the only book I’ve read by Edgerton. From what I’ve found online, she began writing with a series of alchemical fantasies, the Celydonn trilogy: Child of Saturn and The Moon in Hiding in 1989, followed by The Work of the Sun in 1990. Goblin Moon came out in 1991, as did its sequel, The Gnome’s Engine; the two books together make up the “Masks & Daggers” duology. A second Celydonn trilogy followed (The Castle of the Silver Wheel in 1993, The Grail and the Ring in 1994, and The Moon and the Thorn in 1995), but after 2001’s The Queen’s Necklace, the vagaries of the publishing industry led Edgerton to assume a pseudonym. Under the name Madeline Howard, she’s published two books of a projected trilogy — The Hidden Stars and A Dark Sacrifice. Having acquired the electronic rights to her older books, she’s begun re-releasing them as ebooks and print-on-demand paperbacks. Goblin Moon’s now available at her website, with The Gnome’s Engine apparently planned to re-appear in a few months.

Moon’s an intricate and surprising book. The plot follows the fortunes of several characters: river scavengers who make a surprising find, an old used bookman who thinks he knows how to use said find, his granddaughter who is the best friend of an ailing upper-class cousin, and a mysterious nobleman with strange and possibly dreadful secrets. These plot strands run into each other unexpectedly, branch out in surprising directions, and finally more or less dovetail into a conclusion. There are elements in Goblin Moon of romance, mystery, and adventure out of Dumas or Orczy. But what really makes the book stand out is its setting, an elaborate secondary world. Most of the book takes place in and around Thornburg, a pseudo-German city in an eighteenth century filled with magic, fairies, dwarves, gnomes, trolls, and a moon whose orbit brings it visibly closer to the earth at its full. The outlines of Thornburg and the wider world are familiar, evocative of the exploits of Casanova or Cagliostro, but the details are specific, unique, and highly detailed: Edgerton’s imagined her world’s folkways and superstitions, its magic and iconography, its habits of thought and obsessions.

You could call it steampunk, if you’re broadminded. Personally I feel that it’s something in-between steampunk and medieval fantasy; it’s not quite a fantasy of manners, but close. As I said, it’s a fantasy of the eighteenth century, and revels in the weirdness of that specific era. You can find analogues here for the Hell-fire Club and the Freemasons, you can find alchemists and coffee-houses, you can find apothecaries and fairy godmothers out of some salon fairy tale. It’s a brilliant re-imagining of the pre-Romantic era.

You could call it steampunk, if you’re broadminded. Personally I feel that it’s something in-between steampunk and medieval fantasy; it’s not quite a fantasy of manners, but close. As I said, it’s a fantasy of the eighteenth century, and revels in the weirdness of that specific era. You can find analogues here for the Hell-fire Club and the Freemasons, you can find alchemists and coffee-houses, you can find apothecaries and fairy godmothers out of some salon fairy tale. It’s a brilliant re-imagining of the pre-Romantic era.

As a point of comparison, Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell is worth mentioning, though Goblin Moon plays with an era a few decades before Clarke’s terrain. I also don’t think Edgerton’s quite as technically gifted stylistically as Clarke is. The writing’s solid enough, but less a pastiche of its era. Instead, Edgerton’s book stands out through the quality of its sustained imagination and the completeness of its world-building. It vaguely reminds me of Hope Mirrlees’s Lud-in-the-Mist in the way it builds a convincing community, complete with a collective imagined history and set of imagined folk beliefs.

There’s a density and detail of imagination that works to build a world; and it’s the world that sustains the interest, as much or more than the plot. Consider the following description of an inn:

The tavern known as the Antique Squid was a great untidy elephant of a house, built of grey stone and half timber, with dormer windows and cupolas and chimneys starting out of the roof and the upper stories in unexpected places. It was a crazy old house, all curves and odd angles, with shutters hanging loose on broken hinges, doors that regularly jammed (or refused to close at all), and a slate roof carpeted in a patchwork of shaggy green moss and ruddy houseleek.

The taproom at the Squid was long and narrow, rather resembling an attic lumber room for its low, beamed ceiling and the number and variety of its furnishings: scarred oak tables, upholstered armchairs with broken seams and horsehair sticking out in wiry tufts, benches, settles, stools both high and low, trunks, and packing crates. In addition, the taproom boasted two fine fireplaces, each with a cozy inglenook, a dozen or so clocks (some of these even kept time), and a number of dim old paintings done in oils. Perhaps the most striking feature was the many-tentacled sea-creature preserved in formaldehyde in a bottle behind the bar, the antique squid for which the tavern was named.

The tavern had a reputation for solid comfort combined with a convivial atmosphere. Folk came to the Squid for good brown beer and well-aged cheeses, for steaming bowls of purl or mulled wine, for demon fiddlers who could play all night long with scarcely a pause, and for comely, good-natured barmaids.

The bar doesn’t play much of a role in the book. In this particular chapter, it serves as the setting for a conversation. And it’s mentioned another time or two. The description, at first blush, seems out of proportion to the tavern’s relevance to the plot. In a sense it is, but my point is that seeming digressions like this give far more to the story as a whole than merely plot-centered information.

From this description of the inn, we learn what kinds of food and drink are favoured by the none-too-well-off in the city. We learn what kinds of diversions draw them (demon fiddlers). We learn that even a tavern has old paintings up on its walls. We learn also what sort of atmosphere gives “solid comfort” to residents of Thornburg.

From this description of the inn, we learn what kinds of food and drink are favoured by the none-too-well-off in the city. We learn what kinds of diversions draw them (demon fiddlers). We learn that even a tavern has old paintings up on its walls. We learn also what sort of atmosphere gives “solid comfort” to residents of Thornburg.

More than that, the inn comes to seem like a stand-in for the book itself. Bristling with odd extensions, built of unexpected curves, an untidy elephant of a tale. By choosing the tavern of all buildings to describe, the book helps build the world and establish something of the nature of the city; but it also presents an image of itself, and so emphasises that the feel of the setting and the structure of the story have something in common. Which isn’t surprising, really. In a lot of ways the story seems to emerge from the setting.

It’s not just that the characters of the book feel like they could only have emerged from this specific setting — though they do. It’s more that the world-building is so complete, it brings about the story naturally as the characters live their lives and follow their natural paths. The setting shapes the action. As the characters explore their world, just as naturally as anyone living in any world comes to explore their environment, the narrative emerges from their actions.

I should note that occasionally the sense of immersion in the world was broken, at least for me. I don’t know that there was any way around it, though, because it comes back to questions of names and nomenclature. Most of the countries in this world are close parallels to our own (Spagn, Ruska, Ynde) but then at one point someone refers to ‘china’ in the sense of ceramics. There are some places that have the same names as places in this world (there’s mention of the Alps), but you still can’t help but be thrown when there’s an off-hand reference to a (period-accurate) carriage called a ‘berlin.’ Personally, I found myself also noticing names from a distinctive culture of this world (Ezekiel) or deriving from some specific cultural association (Francis, meaning ultimately ‘Frenchman’ by way of the Franks). Different readers will have different reactions, and one can plausibly argue that any apparent similarity of names between that world and this is a case of parallel development — there happens to be someplace or someone named ‘China’ and ‘Berlin’ in that world, and in some way we happen not to know, they bestowed their name on a kind of porcelain and a kind of carriage. But it still feels distracting.

I should note that occasionally the sense of immersion in the world was broken, at least for me. I don’t know that there was any way around it, though, because it comes back to questions of names and nomenclature. Most of the countries in this world are close parallels to our own (Spagn, Ruska, Ynde) but then at one point someone refers to ‘china’ in the sense of ceramics. There are some places that have the same names as places in this world (there’s mention of the Alps), but you still can’t help but be thrown when there’s an off-hand reference to a (period-accurate) carriage called a ‘berlin.’ Personally, I found myself also noticing names from a distinctive culture of this world (Ezekiel) or deriving from some specific cultural association (Francis, meaning ultimately ‘Frenchman’ by way of the Franks). Different readers will have different reactions, and one can plausibly argue that any apparent similarity of names between that world and this is a case of parallel development — there happens to be someplace or someone named ‘China’ and ‘Berlin’ in that world, and in some way we happen not to know, they bestowed their name on a kind of porcelain and a kind of carriage. But it still feels distracting.

And, if the plot emerges from the setting, it still ambles rather more than it accelerates. It proceeds mostly through a series of discussions rather than adventurous incident. If its various strands do come together at the end, it’s still not quite a rousing climax. Still, Edgerton displays a sharp if not ruthless eye for what to leave out of her story, moving things along briskly. The building of the complex tale through the various strands is nicely-handled as well. Ultimately, the conclusion is at least satisfying, while also preparing the way for the second book in the duology.

I’m happy to hear that book will be re-released soon. Edgerton’s characters weren’t especially deep, but they fit their world perfectly, and one feels after Goblin Moon that they still have depths worth exploring in a further story (maybe more than one; Edgerton’s got an excerpt from a third novel featuring one of the characters on her web site). These books are worth finding and reading to see what a world can do.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

This and its sequel are indeed a lot of fun. I haven’t read her two latest books but they’re prequels (by several centuries and a cataclysm) to “Goblin Moon”.

Nice to see one of fantasy’s most-underrated writers receiving some attention here. I absolutely love Theresa Edgerton’s work, particularly Goblin Moon; she is one of the few authors in the genre with the ability to convey a genuine sense of life and beauty to the reader.

[…] David Surridge’s thoughtful review of Goblin Moon last month. You can read the whole thing here, but it was this paragraph that really hooked […]

[…] David Surridge reviewed Teresa Edgerton’s Goblin Moon (1991) here at Black Gate early last year, and here I am to […]