Review of K. Bird Lincoln’s Tiger Lily

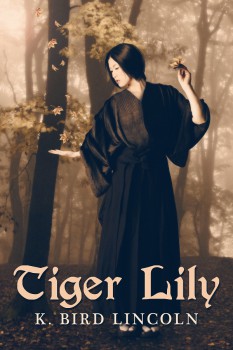

About a month and a half ago on this blog, I solicited submissions of self-published novels for review. I know firsthand how difficult it is to sell fiction on your own, so I wanted to give some attention to books that are often underappreciated, both by the industry and by readers. I received more than a few submissions–not so many that I was completely swamped, thankfully, but enough that I had to sort through the entries and decide on the one that I thought was most promising. That one was Tiger Lily by K. Bird Lincoln.

I selected this novel because the sample chapter was well-written and the premise was unique and intriguing. However, I was going out of my comfort zone in choosing it. Tiger Lily could be best described as a fantasy historical romance taking place in feudal Japan. I’ll readily admit that that is not my normal reading material. Since I am not as familiar with this subgenre, it’s quite possible that common and accepted tropes of it struck me the wrong way, and that I completely missed things that would bother the normal audience. So in this review, I’ll just point out what worked for me and what didn’t, and those with more familiarity with the subgenre can take what I say with a grain of salt.

The title, Tiger Lily, refers to the main character, Lily-of-the-Valley, who was born in the year of the Tiger, which she blames or credits for every stubborn and rebellious decision she makes. She’s unmarriageable, she’s a failure as a dutiful daughter, and worst of all, she keeps the old ways of Jindo, rather than the new Buddhist religion embraced by the Emperor. The author admits that she sharpened the conflict between Buddhism and Jindo in the novel, as compared to the historical competition between the two faiths in Japan. Though it may be more fantasy than history, this conflict is effective as the driving force in the novel. It’s the main motivation for Lily to keep her connection to the spirits, or kami, hidden, and is the ultimate reason behind the war she finds herself embroiled in, between the Buddhist Emperor and the Jindo-following rebels.

At the beginning of the novel, Lily doesn’t consider herself a follower of Jindo so much as of her vanished mother, who was a true practitioner. She merely enjoys walking alone in the forest, singing the forbidden songs that her mother taught her. Until one day she runs into the local lord’s son, Prince Ashikaga, injured in the forest, and she must protect him from the fox spirit rebels. Her songs are what allow the prince to fight and defeat the rebels in the early skirmishes. Soon she’s swept up in the war against the Jindo rebels, where the prince sees her as the key to success, and maybe as something more. But as they become closer, she learns that the prince has his own secrets. I won’t reveal that here, but if you know that he has a secret (which the book description tells you straight out), it’s fairly obvious what it is.

I was disappointed by how little the secrets seemed to matter in this story. Lily is terrified of what would happen if her secret is revealed, so much so that she does her best not to use her songs even when they are desperately needed, but once everyone finds out, there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of consequences. Sure, the intolerant Buddhist Abbot wants to imprison (and possibly execute) her, but Prince Ashikaga protects her and that’s that. And when Lily discovers the prince’s secret, she’s much more concerned about what it means that he revealed it to her, than what the secret itself means.

As for Lily herself, I found her greatest weakness to be her passivity, which is very much at odds with how she views herself. She works so hard not to be the rebellious Tiger she believes herself to be that she behaves more as an observer than an actor, letting others drag her along–whether it’s the prince, her sister, or the kami. We see her thoughts and concerns, but she never seems to share them with anyone else, leading others–the prince especially–to easily avoidable misunderstandings. And when things get too intense, she’s more likely to run than to fight. Even her constant worrying about her Tiger stubbornness seems like it’s an attempt to evade culpability for her own mistakes and bad decisions.

But she does grow in the course of the story. When the climactic moment comes, she finally takes her fate into her own hands. What seemed a monumentally bad decision on her part is revealed to have at least the beginnings of a noble and clever plan–even if it is undercut by poor follow-through and a close call with temptation.

The climax works largely because it subverts many of the expectations which have been built into the story. Up to this point, the conflict between Jindo and Buddhism has been one-sided, where Jindo has all the best arguments (and magic), so much so that it is hard to see why Lily, with her direct connection to the kami, is helping the Buddhist prince. But in the climax, when we finally meet the wise master who could have made the decisive case for Jindo, the purity of his beliefs are undermined by the hypocrisy of his practices, and Ashikaga is, if not eloquent, still persuasive in his belief in the virtues of the Buddhist doctrine. In that moment, Lily siding with the prince is finally believable, rather than a rationalization for the romance plot.

As should be apparent, I enjoyed the ending more than the lead up. There were some rough patches on the way there, where the action dragged and the prose was clipped and unpolished. But I wasn’t disappointed in the payoff.

Tiger Lily is available on Amazon for $3.99, and is part of the Kindle Select program, so Amazon Prime members can read it for free.

If you have a self-published novel that you would like me to review, please see the guidelines here.

Donald S. Crankshaw’s work first appeared in Black Gate in October 2012, in the short novel “A Phoenix in Darkness.” He lives online at www.donaldscrankshaw.com.