Vintage Bits: In Search of the Lost Black Crypt

Some 20 years ago, shortly after I graduated from the University of Illinois, I bought my first home computer. It was an Amiga 2000, essentially the same as the entry-level Amiga 500 but with a hard drive. The hobby computing industry — which is now dead — was booming in the early 90s, and there were thousands of fun things the dedicated hobbyist could do with a decent home computer. Video editing, BASIC programming, ray trace imaging, indexing Chicken Cacciatore recipes… and if you were cutting edge enough to buy a modem, you could even log into BITNET and post on those electronic bulletin boards everyone was talking about. Crazy.

Some 20 years ago, shortly after I graduated from the University of Illinois, I bought my first home computer. It was an Amiga 2000, essentially the same as the entry-level Amiga 500 but with a hard drive. The hobby computing industry — which is now dead — was booming in the early 90s, and there were thousands of fun things the dedicated hobbyist could do with a decent home computer. Video editing, BASIC programming, ray trace imaging, indexing Chicken Cacciatore recipes… and if you were cutting edge enough to buy a modem, you could even log into BITNET and post on those electronic bulletin boards everyone was talking about. Crazy.

All of that was very interesting. But I shelled out my $1,500 bucks for one reason, and one reason only: to play games. And that’s exactly what I did.

I played the role playing games I’d been aching to try out in my last year of grad school, while feverishly finishing my Ph.D. thesis: Pool of Radiance, Bard’s Tale, Dragon Wars, many others. I played late into the night, before dragging my weary butt into work at Amoco Oil the next morning. It was an exhausting and emotionally draining lifestyle but, let’s face it, those dungeons weren’t going to clean themselves out. Countless terrified townspeople in tiny electronic villages were counting on me, and I wasn’t going to let them down.

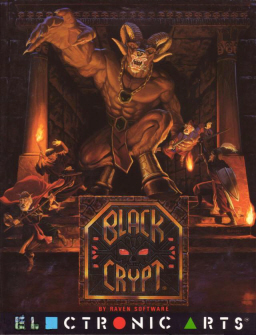

About a year after I bought my Amiga, in March 1992, Electronic Arts published one of the most acclaimed role playing games ever made for that platform: Black Crypt, the first release from Raven Software, future makers of the popular Hexen, Soldier of Fortune, Quake 4, and Call of Duty: Modern Warware 3. Inspired by the legendary game Dungeon Master, another famous Amiga title, Black Crypt was nothing less than a vast trap-filled dungeon crammed with monsters, secret passages, hidden switches, and magical loot. The graphics were gorgeous, and the wonderful sound effects — the distant clanking of trapdoors, odd footsteps, and telltale sounds of the teleporters — immersed players like never before, and made you want to play with the sound cranked up and the lights turned down low.

I played the first few levels and was mesmerized. Then, in November 1992, I got married and moved to Belgium, leaving my beloved Amiga behind. I thought about the game many times in the intervening years, as I returned to the States, got a job at a tiny software company, worked on Internet Explorer 1.0, and was at ground zero of the Internet revolution that transformed the entire country. Some time during those turbulent years, my Amiga was moved to the basement, where it quietly sits today, collecting dust.

In the last few weeks, I’ve been on a quest to find and complete Black Crypt. It’s a quest filled with exactly the kind of twists and turns you’d expect for a man determined to find a long-lost crypt, spoken of only in half-forgotten legend. While critics raved, Black Crypt was released when the Amiga was already in decline, and was never successful enough to be ported to any other platform. It vanished quickly, both from store shelves and collective memory. As I search for the right magical tools that will allow me to open the crypt, I’m well aware that it’s not going to be easy.

But that’s okay. After twenty years, one of the things I’ve learned is that true joy isn’t always in the destination. It’s in the journey.

Our most recent Vintage Bits articles were Sword of Aragon, Lordlings of Yore, and Battletech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception.

Once upon a very suspect time, a human being by the name of Terry Pratchett conjured up a space-traveling sea turtle by the name of A’tuin, and proceeded to make a sizable fortune from the disc-shaped world he emplaced upon her. In Pratchett’s Discworld novels, magic of the most unpredictable kind is the norm, and so it should come as no surprise that, eventually, somebody had to commit his unique brand of literary lunacy to celluloid.

Once upon a very suspect time, a human being by the name of Terry Pratchett conjured up a space-traveling sea turtle by the name of A’tuin, and proceeded to make a sizable fortune from the disc-shaped world he emplaced upon her. In Pratchett’s Discworld novels, magic of the most unpredictable kind is the norm, and so it should come as no surprise that, eventually, somebody had to commit his unique brand of literary lunacy to celluloid.

A little while ago, Fearless Leader John O’Neill

A little while ago, Fearless Leader John O’Neill