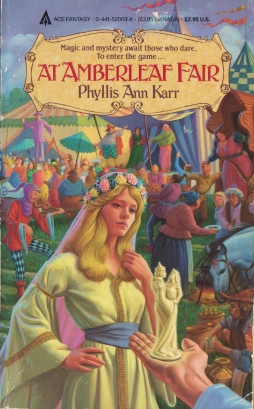

Phyllis Ann Karr’s At Amberleaf Fair

For some time I’ve had the idea that there are unknown treasures yet to be mined in the deep veins of 80s fantasy. That among all the many titles published in those years are overlooked tales that are worth digging up. I don’t necessarily mean neglected masterpieces, though that’s possible. I mean little gems: books offering unexpected or idiosyncratic takes on the genre. Books that to some extent operate by conventions of their own. Books that suggest slightly different ways to do things. I want to write here about an example of what I mean: Phyllis Ann Karr’s At Amberleaf Fair.

For some time I’ve had the idea that there are unknown treasures yet to be mined in the deep veins of 80s fantasy. That among all the many titles published in those years are overlooked tales that are worth digging up. I don’t necessarily mean neglected masterpieces, though that’s possible. I mean little gems: books offering unexpected or idiosyncratic takes on the genre. Books that to some extent operate by conventions of their own. Books that suggest slightly different ways to do things. I want to write here about an example of what I mean: Phyllis Ann Karr’s At Amberleaf Fair.

Karr’s published poetry, essays, and short stories, as well as The Arthurian Companion, are a sort of encyclopedia of Arthuriana I find immensely useful. Her first novels were published in 1980, which saw both the romance My Lady Quixote and the fantasy Frostflower and Thorn. She’s published several other novels since, some under the name Irene Radford; At Amberleaf Fair came out in 1986. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy tells me that several of Karr’s short stories feature Amberleaf Fair’s main character, but that (as of the Encyclopedia’s publication) none have been collected.

Amberleaf Fair is named for the gathering at which its story takes place. It’s an autumn trade fair in the community of East’dek. A toycrafter, Torin, proposes marriage to Sharys, a magician and healer in training; but it looks like she’ll instead choose Torin’s friend, an adventurer named Valdart. Then Torin’s brother, an accomplished ‘magic-monger,’ is struck down with some sort of illness; Valdart’s ceremonial present to Sharys, effectively his marriage proposal, is stolen and the evidence points to Torin. Torin and his friend, the storycrafter Dilys, try to work out what has happened, along with a judge named Alrathe — but the story is less about the mystery and more the tale of the relationships of the various characters as the fair goes on, and their choices in life, and how they balance their desires and their duties to their family or society. It’s understated, quick, and entertaining.

The plot moves forward dextrously and crisply, mostly alternating between the perspectives of Torin, Dilys, and Alrathe, with only the latter really involved in the matter of the stolen marriage present. The mystery’s not that hard to unravel, but makes for a solid frame on which to hang the character-oriented drama. Stylistically, the book’s solid, even terse, with minimal physical description. The prose is workmanlike, with few high-flown passages. But it handles large amounts of exposition easily, making it tell us about character as well as the world. Here’s the start of the second chapter:

At thirty-five years old, one did not often find oneself Senior Storycrafter at any fair larger than thirty-five tents. Amberleaf Fair had forty-nine tents, not counting the animal shelters. Dilys liked to suspect that some of her mentors had made their excuses of minor illness, distance, or desire for rest in order to give her this experience.

She relished it all: choosing a pavilion site at the edge of the grounds, hanging lanterns in the forest to create an artistic play of shadows on the cloth walls, scheduling those adventurers who wanted to sell their tales between herself, Brinda, and Kivin. Four of the adventurers were older than Dilys, and Torin’s friend Valdart was the same age, and that made her job even more enjoyable. Settled storycrafters always held authority over wanderers, who told tales only as a byproduct of their travels.

That’s a nice mix of general information about the world (the habits and hierarchies of storytellers), specific information about Dilys (her age, how she feels about other storytellers, how she feels about her job), and a bit of visual information as well (the image of the lanterns in the forest). It’s all very tight and efficient.

But what I think makes the book interesting are really two things. Firstly, the amount of worldbuilding, the unobtrusively complete imagining of a society. And, secondly, the resolutely small scale of events, combined with a willingness to avoid melodrama in favour of an almost pastoral sensibility.

But what I think makes the book interesting are really two things. Firstly, the amount of worldbuilding, the unobtrusively complete imagining of a society. And, secondly, the resolutely small scale of events, combined with a willingness to avoid melodrama in favour of an almost pastoral sensibility.

In terms of the worldbuilding, the book has a very solid grasp of how magic works, and how it’s worked into the fabric of society. There’s no attempt here to simulate the European Middle Ages. There’s no concern with historical accuracy. There is only the world of the book, a world built from the ground up.

The way that world works fits with the plot of the story. The fact that presents are given as a form of marriage proposal is the springboard for the action. The way semi-independent judges arbitrate disagreements allows a character to take on the role of detective, complete with a final scene in which all accumulated mysteries are neatly explained and all things set in order.

But more than that, individual quirks of the world are mentioned, and then used to help develop character. How names work, for example: one adds syllables to one’s name as one ages and gains status. Most people have three syllables in their full, formal name, and a few have four; old friends will call each other by a shorter two-syllable version of their name, but to use a one-syllable version is an insult. That comes out through the story, the characters using longer or shorter versions of each others’ names in accordance with their emotional state and what they want to express.

But more than that, individual quirks of the world are mentioned, and then used to help develop character. How names work, for example: one adds syllables to one’s name as one ages and gains status. Most people have three syllables in their full, formal name, and a few have four; old friends will call each other by a shorter two-syllable version of their name, but to use a one-syllable version is an insult. That comes out through the story, the characters using longer or shorter versions of each others’ names in accordance with their emotional state and what they want to express.

The magic in the world is mostly small-scale transmutation and animation of inanimate objects, with some telepathy and illusion generation. Its laws are nicely explained, which is good since it’s a loophole in the magic system that leads to the mystery; but it’s not just ‘explained’ in the sense of having its rules laid out. It’s integrated into the world. The culture of East’dek is built out of it.

Karr’s created a whole world, not on the large scale of countries or even cities, not in the development of an extensive history, but on the smaller scale of how the fair operates; how families work and how careers are handed down generation to generation; how men and women relate to each other; how food is made. How trade works. What people expect of their lives.

There’s a certain pleasure in noting the details of the setting; not all of those details are obvious. I have to admit I didn’t at first notice (until it saw it pointed out on the book’s Goodreads page) that Alrathe is apparently genderless, or perhaps hermaphroditic — gender-specific pronouns are not used with reference to the judge, another character at their first meeting is confused about Alrathe’s gender, yet another is taken aback at his first sight of the judge for no specified reason, and once Alrathe reflects that “Like most individuals similarly circumstanced, Alrathe had decided early against trying for life mate and children.” What ‘similarly circumstanced’ means is left ambiguous.

There’s a certain pleasure in noting the details of the setting; not all of those details are obvious. I have to admit I didn’t at first notice (until it saw it pointed out on the book’s Goodreads page) that Alrathe is apparently genderless, or perhaps hermaphroditic — gender-specific pronouns are not used with reference to the judge, another character at their first meeting is confused about Alrathe’s gender, yet another is taken aback at his first sight of the judge for no specified reason, and once Alrathe reflects that “Like most individuals similarly circumstanced, Alrathe had decided early against trying for life mate and children.” What ‘similarly circumstanced’ means is left ambiguous.

But beyond such things, the world of the fair is full of charming details. Money takes the form of carved stones, the smaller being more valuable. Oral storytelling is a valued craft, and audiences sing their applause. Professions and status are indicated by the colour of one’s robes. Children are disciplined by being made to hold their arms out unsupported. At death, one plants a tree in one’s grave — setting up a minor association of death with autumnal imagery, ironically belied by the marriages that close the autumnal Amberleaf Fair.

It’s charming, and all effectively worked into character moments. Character and setting are interwoven, in other words. Personalities derive naturally from the society that fosters them. And the mystery plot helps bring out the details of the world: because the characters are trying to understand what happened, they rehearse in their own minds their memories and what they already know, looking for answers.

But worldbuilding aside, in some ways what may be most remarkable about the book is the way it avoids melodrama and high-stakes conflict. The mystery plot provides little tension; the characters aren’t really worried about the value of the stolen item. It’s important only because of the wedge it drives between Torin and Valdart. And because whether it’s found or not may have a bearing on Sharys’ future. There’s no murder in the book, no impending sense of disaster. It’s a novel of everyday life, in a world where life to us seems fantastic.

But worldbuilding aside, in some ways what may be most remarkable about the book is the way it avoids melodrama and high-stakes conflict. The mystery plot provides little tension; the characters aren’t really worried about the value of the stolen item. It’s important only because of the wedge it drives between Torin and Valdart. And because whether it’s found or not may have a bearing on Sharys’ future. There’s no murder in the book, no impending sense of disaster. It’s a novel of everyday life, in a world where life to us seems fantastic.

I’ve mentioned that the scale of the magic in the book is small, focusing on providing food and crafting goods, not on grand earth-shattering spells. The fair itself, as mentioned in the quote above, isn’t especially large. The book avoids any kind of insistence on the importance of its story; the characters even fear a disease that strikes down boasters and the prideful. The emphasis is on being a solid contributing member of society, not on heroism. Or on melodrama.

Characters worry about their careers, and deciding between jobs, and how to structure their future, and when and whether to have children. You could call it domestic, or pastoral; I came to think of it as a comedy that wasn’t trying to be funny — a serious story that ends well, with the pattern of life restored. By the end of the book, characters are married off and mysteries solved. The detective-novel resolution scene, when riddles are unriddled and enigmas explained, is a symbolic setting-in-order of all things, the final resolution of the world’s pattern.

The result of all this is distinctive. I can’t call it great; I didn’t find the imagery resonant enough, or the prose powerful enough. But it’s a fine read, character-centred in an unusual way. It would be wearying if every book tried to do what At Amberleaf Fair does, but it’s nice to have the book as an example of the variety you can find in genre fantasy novels. And as encouragement to keep looking, in the hope of finding more such distinctive work.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

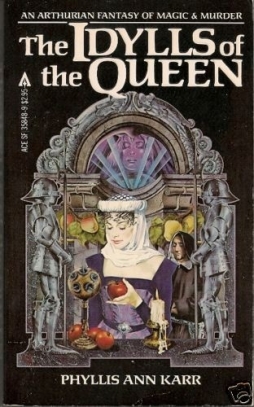

Even though it seems more targeted at women readers, the amazing cover art for ‘At Amberleaf Fair’ has me itching to read it. xD

You know, I’m not honestly sure if it was aimed at women or not. I tend to be lousy at assessing that sort of thing. But it’s a good book, either way. And you’re really right about the cover art — it’s actually a lovely wraparound cover, too. Unfortunately I can’t find a scan online.

[…] on, then find some small detail that throws everything into question. A made-up culture might have details of meaning in its dress or behaviour that only reveals itself gradually. And in both mimetic and fantastic literature, some stories live […]

Good review.

I was amused that it turned out to be a book from the 80s, because when this page loaded in my browser my eyes were immediately drawn to the image of the book cover. I recently spent WEEKS sorting through 10k old books and giving half to charity, and that style of artwork really screams out “1980s fantasy” (the Myth books by Asprin had covers a lot like that).

Only after I started reading the article was I relieved to note that the style had not come back into vogue. 😉

[…] Phyllis Ann Karr’s At Amberleaf Fair […]

[…] I’ve mentioned before that I’ve an idea that there’s a lot to be learned from some of the overlooked fantasies of the 1980s. Teresa Edgerton’s Goblin Moon was published in 1991, and it’s less obscure than some — in fact, it’s just been come out as an ebook (you can find a trailer here) — but it’s still a good example of what I have in mind. And a fine and delightful tale in its own right. […]

[…] mentioned a few times before that I have a fascination with 80s fantasy, and suspect a number of now-overlooked […]

[…] little while ago I wrote here about Phyllis Ann Karr’s 1986 novel At Amberleaf Fair. I thought it was well-written and inventive, quietly doing highly distinctive things with the […]

[…] written here before about my fascination with underexplored elements in 80s fantasy. In this context I have […]