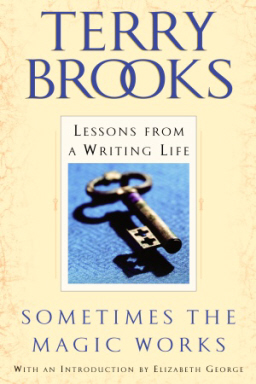

Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Sometimes the Magic Works

After last week’s post on John Gardner’s curmudgeonly classic The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers, it seemed important to look at a writer’s handbook by an unrepentant writer of genre fiction — commercial fiction, even. I wanted a book that was humble where Gardner’s was imperious, practical about the business of publishing where Gardner’s was aloof from it.

After last week’s post on John Gardner’s curmudgeonly classic The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers, it seemed important to look at a writer’s handbook by an unrepentant writer of genre fiction — commercial fiction, even. I wanted a book that was humble where Gardner’s was imperious, practical about the business of publishing where Gardner’s was aloof from it.

Gardner suggests that the young writer read all of Faulkner, and then all of Hemingway to clear Faulkner’s excesses out of her mind. So I turned to Sometimes the Magic Works: Lessons from a Writing Life by Terry Brooks to recover from all that is magisterial in The Art of Fiction.

A confession: Terry Brooks’s novels are not my thing. That is not a judgment on him, just an observation that so far I haven’t really connected with his work. For the record, in the Grand Taxonomy and Hierarchy of Books That Aren’t My Thing, The Sword of Shannara gave me far more reading enjoyment than did James Joyce’s Ulysses.

A confession: Terry Brooks’s novels are not my thing. That is not a judgment on him, just an observation that so far I haven’t really connected with his work. For the record, in the Grand Taxonomy and Hierarchy of Books That Aren’t My Thing, The Sword of Shannara gave me far more reading enjoyment than did James Joyce’s Ulysses.

A lot of people — critics, teachers, readers, other writers — have judged Brooks harshly for one reason and another. But I will go to school on anybody, absolutely anybody, who seems to know something I don’t. Am I on the bestseller lists yet? No? Then Brooks knows something I don’t. I’m hoping that readers who do connect with his books will stop by the comment thread and share their perspectives.

The Brooks manual has two main areas of insight to offer that balance what’s missing in Gardner, and those two areas couldn’t be more different.

In chapters like “I Am Not All Here” and, surprisingly, a chapter on the importance of outlining called “The Dreaded ‘O’ Word,” Brooks talks about the importance of daydreaming. Though Gardner speaks eloquently of fiction as a continuous waking dream for the reader, he stresses that this dreamlike experience is an illusion achieved by the writer by means of titanic conscious effort.

In chapters like “I Am Not All Here” and, surprisingly, a chapter on the importance of outlining called “The Dreaded ‘O’ Word,” Brooks talks about the importance of daydreaming. Though Gardner speaks eloquently of fiction as a continuous waking dream for the reader, he stresses that this dreamlike experience is an illusion achieved by the writer by means of titanic conscious effort.

Often true, yes. But for many writers, myself included, all of that conscious effort must come after a prolonged process of half-conscious reverie. Never outside of Brooks’s outlining chapter have I seen such a cogent explanation of the relationship between reverie and organization.

On the business side, three chapters stand out. “It’s Not About You,” seems at first to be about the ego-bruising side of book signings — and it is about that, and how to cope usefully with it — but the chapter turns out to be a sort of manifesto in favor of authorial humility and personal connection with readers. Right-mindedness is inseparable from the brass tacks practicalities of handselling copies.

On the business side, three chapters stand out. “It’s Not About You,” seems at first to be about the ego-bruising side of book signings — and it is about that, and how to cope usefully with it — but the chapter turns out to be a sort of manifesto in favor of authorial humility and personal connection with readers. Right-mindedness is inseparable from the brass tacks practicalities of handselling copies.

The other two stand-out chapters recount two very different experiences writing tie-in novels for movies. Hollywood temptation would be a great problem to have, and if I ever face it myself, I will measure my opportunity on the continuum between Brooks’s grueling, galling experience writing the tie-in for Spielberg’s Hook and his joyful experience writing the tie-in for Lucas’s The Phantom Menace.

If you are, yourself, a curmudgeonly reader, this book is probably not for you. The introduction by Elizabeth George is riddled with sentence-level grammatical errors and infelicities. In the middle of Brooks’s chapter on his ten rules of good storytelling, he interrupts the rather dreadful story he’s using for an example to say: “I probably could do better if I wanted to spend more time on it, but you get the general idea.” Well, maybe. Sometimes the magic works, and then sometimes Brooks’s prose style runs flat and featureless for paragraphs at a stretch.

If you are, yourself, a curmudgeonly reader, this book is probably not for you. The introduction by Elizabeth George is riddled with sentence-level grammatical errors and infelicities. In the middle of Brooks’s chapter on his ten rules of good storytelling, he interrupts the rather dreadful story he’s using for an example to say: “I probably could do better if I wanted to spend more time on it, but you get the general idea.” Well, maybe. Sometimes the magic works, and then sometimes Brooks’s prose style runs flat and featureless for paragraphs at a stretch.

If you want the best fiction writing manual, you’ll still want Gardner. If you want practical advice on tie-ins, an attitude adjustment when you need to be reminded how lucky you are that you get to write fiction at all, or just a friendly authorial voice that doesn’t demand that you bow to its superiority, maybe you want this book.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

It’s been a few years since I read this book. ‘Sword’ remains one of my all time favorite novels and I’ve read all but a few of the recent Shannara series. I recall this being a shallow, not very helpful book at all. I got very little out of it and didn’t think it useful. It’s buried in a box instead of on my writer’s bookshelf.

Lawrence Block’s ‘Telling Lies for Fun and Profit’, however, is the single best book of its type I have read.

Sherlock, thanks for the recommendation. The Block is one I haven’t read yet.

In matters of craftsmanship, the Brooks book is not helpful. Even if it were, it’s hard to imagine that it could hold its own against John Gardner’s writing books. I remember that when I first read Sometimes the Magic Works, my response was much like yours. I reread it this week with the question, What can I find that this books does well? Honestly, I wasn’t sure going in that I would find anything. It turns out that there is something there, just not what one usually buys a writing book for.

Having read “Sometimes . . .” I can attest that it’s a fun but light weight book about Brooks’s life and his views on writing. For a much better example of a combo bio/writing book I’d recommend Steve King’s “On Writing” which in addition to teaching a good deal about writing is also a sheer pleasure to read.

By the way Lawrence Block is treasure trove of good, solid writing advice. After all Block wrote a monthly fiction column for over 18 years for Writer’s Digest. In addition to “Telling Lies” he’s written several other writing books that are just as good. They include “Write for your life”, “Spider, spin me a web”, “Writing the novel from plot to print”, “The Liar’s Companion”, and “The Liar’s Bible” among others. Plus, while I’m at it I’d also recommend Dean Koontz’s superlative time “How to Write Best Selling Fiction” which is out of print but is easily found via Amazon or ABEBooks.

Randy, I agree about King’s On Writing. That one’s on my docket for a column two or three weeks from now. The Dean Koontz book is one I’d forgotten about. I’ll have to track down a copy. Thanks for the suggestions!

I could not read Brooks. I tried, and failed, on multiple occasions and that was before I understood writing. I can’t imagine trying to read him now. Still, more power to anyone with his amount of success, I say well done!

Scott, I’m with you on Brooks’s novels. Precisely when a writer is Not My Thing, but is The Thing for a lot of other readers, I get curious and hope that I can fill in a blind spot or two. Stephen King is Not My Thing (and maybe that should be the title of a really terrible poem), but On Writing is a book I’m looking forward to talking about here.

[…] Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Sometimes the Magic Works […]