Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Escape as Homecoming

Hurricane Sandy roared and wailed outside our door, shook down trees across the street, pounded our roof so hard my two little sons couldn’t even recognize the sound as rain. “Drum!” insisted my two-year-old. The kids coped fine until the lights went out. Then they panicked.

Hurricane Sandy roared and wailed outside our door, shook down trees across the street, pounded our roof so hard my two little sons couldn’t even recognize the sound as rain. “Drum!” insisted my two-year-old. The kids coped fine until the lights went out. Then they panicked.

Of all the things to fear about a hurricane, darkness is one of the least dangerous. Try telling that to a five-year-old. He can’t wrap his head around why 70 mph winds are worse than wind he’s allowed to play in. He probably could have understood why storm surge is scary if we’d been close to any — fortunately, we’re on high ground and nowhere within sight of a body of water. All the anxiety the boys had detected in the adults around them, all their own anxiety from watching the storm through the windows that day, rushed instantly to compound their longstanding fear of the dark.

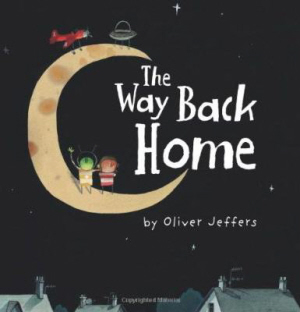

As soon as we had flashlights ready to read by, the kids knew exactly which book they wanted. The Way Back Home is the story of a boy and a Martian who get stranded on the Moon and work together to get themselves and their flying machines back where they belong. Before the boy and the Martian find one another, they huddle in the dark, hearing strange noises, fearing the worst. The boy’s flashlight goes out! My sons wanted that page again and again, because that night the idea of losing the flashlight’s comfort was utterly terrifying.

They had always loved the page on which the characters imagine the worst. “Monster page!” shouts my younger son. On a normal night when we read this book, for every time we make it to the end of the story, we probably backtrack to the monster page half a dozen times–it would be more if the kids got their way. It’s hard to explain to children who are still in very literal-minded stages that the monsters are not real, that the whole point of putting the monsters in the book is that they are imaginary (though in this case the Martian isn’t). The monsters in the dark are perhaps the most real part of the story for my boys, whose dark was monster-infested long before I introduced them to the picture books of Oliver Jeffers.

Why do they ask for this book? Why did they ask for it that night, the first night of a blackout that looks likely to last several more days? And why have they asked for it every night since?

They escape from their room, where their parents insist on dimming the light at bedtime (dastardly!), and flee to the moon, where their fear of the dark seems momentarily vindicated. Older readers give greater weight to endings–we can take comfort and learn lessons from sequences of events, real and imaginary, in ways that young children just can’t. Cautionary tales backfire with kids, Studies Have Shown, because every incident in the story is weighted separately in terms of the child’s interest, with no incident privileged by its position in the sequence. It mattered to me when I bought the book that the fear of the dark was safely overcome. The day has not yet dawned when that matters to my kids. “Monster page! Monster page!” they chant, while my husband and I try to emphasize the triumph of interplanetary teamwork.

They escape from their room, where their parents insist on dimming the light at bedtime (dastardly!), and flee to the moon, where their fear of the dark seems momentarily vindicated. Older readers give greater weight to endings–we can take comfort and learn lessons from sequences of events, real and imaginary, in ways that young children just can’t. Cautionary tales backfire with kids, Studies Have Shown, because every incident in the story is weighted separately in terms of the child’s interest, with no incident privileged by its position in the sequence. It mattered to me when I bought the book that the fear of the dark was safely overcome. The day has not yet dawned when that matters to my kids. “Monster page! Monster page!” they chant, while my husband and I try to emphasize the triumph of interplanetary teamwork.

It’s not just that stories about confronting fear show us how we might win despite it, or that stories about bigger and cooler fears than ours put our fears in perspective, or that they lift us out of our small lives–though all of that does happen. The brain in early childhood is not the brain of adulthood. We’re running different software on different hardware, and the adult memory of having been a child is not a reliable window into what children experience. They’re friendly aliens to us, as we are to them. There’s something about a story’s ability to lead you right into the thick of what you wish you could escape from that is comforting. In a way I haven’t quite figured out, that sometimes is the way back home.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

You’re absolutely right about a child’s inability to sequence a story. The scariest book ever written, THERE’S A NIGHTMARE IN MY CLOSET, is supposed to be reassuring: by the end, the nightmare and the child are friends. It isn’t. What’s scary is the simple fact, readily apparent to any fearful child (read: me), that every single time you open the book’s cover, THERE WILL BE A NIGHTMARE IN THE CLOSET. By presenting a nightmare in the first place, the book validates a child’s actual fear that there MIGHT be nightmares…and conquering them is beside the point.

Glad you avoided the worst of Sandy. Good post!

I brought a flashlight to work just so I could be sure of not facing the choice between going back into the storm or fumbling up the stairs from the garage in the dark.

Mark, you might remember the Ballad of the Lower Case N from the early years of Sesame Street. When I was my older kid’s age, I used to sob my heart out over the Lower Case N’s plight, to the utter bafflement of my parents. “But at the end, there are two of them, and they’re not lonely anymore!” my mother would insist. It didn’t matter–every time that snippet ran on a Sesame Street episode, the n was lonely all over again.

My favorite study on kids not privileging the endings of stories is one in which new readers with younger siblings were given a Berenstain Bears book about how to replace sibling rivalry with sibling harmony. The kids who got the book, in which the older bear sibling learns to stop hitting the younger one, had dramatic increases in violence against their sibs, while the control group kids had no change in sibling conflict. The kids imitated what they read about, without any apparent thought to the consequences of those actions that were illustrated in the story.

Mary, I hope you’re recovering well from the storm. Last night, I had to post from the home of a neighbor who has a generator. Tonight I get to use my own computer in my own house. Electricity is a beautiful thing.