Adventure on Film: The Thief of Baghdad

On a recent Friday night, I sat down with my wife to watch The Thief of Baghdad (the definitive Korda/Powell version, from 1940). Thirty minutes later, my wife was fast asleep. When she woke up, she said, knowing I planned to mention the film to Black Gate’s readership, “What are you going to write about this?” Her notable lack of enthusiasm could, of course, be due to any number of factors, but only three reasonable alternatives present themselves: A) my wife is entirely lacking in taste; B) my wife has been replaced by a cantankerous alien entirely lacking in taste; C) this particular movie might well cause many a discerning viewer to harbor similar sentiments.

On a recent Friday night, I sat down with my wife to watch The Thief of Baghdad (the definitive Korda/Powell version, from 1940). Thirty minutes later, my wife was fast asleep. When she woke up, she said, knowing I planned to mention the film to Black Gate’s readership, “What are you going to write about this?” Her notable lack of enthusiasm could, of course, be due to any number of factors, but only three reasonable alternatives present themselves: A) my wife is entirely lacking in taste; B) my wife has been replaced by a cantankerous alien entirely lacking in taste; C) this particular movie might well cause many a discerning viewer to harbor similar sentiments.

Let’s be clear: The Thief of Baghdad is one of the most universally acclaimed fantasy films ever made. Even my old (well-loved) copy of The Movie Guide gushes. “Perhaps the most splendid fantasy film ever made,” writes James Monaco and his various contributors, ending the review with “Film fantasy just doesn’t get much better than this.” Halliwell’s is equally enthusiastic, and they don’t like anything. Time Out raves. Coppola and Lucas cite it as a significant influence.

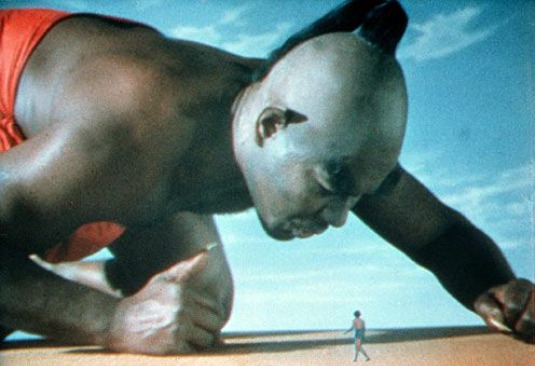

The story is crackerjack from start to finish. (Spoilers here: if you don’t want the plot, skip to the next paragraph.) Ahmed, the king deposed by Jaffar, his own Grand Vizier, falls in love with a princess whom no man can see, and of course vows to see her repeatedly. Ahmed is aided by Abu the thief, but of course Jaffar has designs on the very same princess. When Jaffar kidnaps her, Ahmed and Abu follow, but Jaffar conjures up a storm that separates our two heroes. In order to find Ahmed again, Abu must gain the reluctant help of a fifty-foot genie (the exceptional Rex Ingram), then steal the Eye of the World from a temple guarded by, among other things, a giant spider and giant octopi. Finally, with Ahmed captured and about to be beheaded, Abu swoops in on a flying carpet to save the day.

Given all this, how on earth did my wife (or some random alien) pass out?

The Thief of Baghdad has not aged gracefully. It’s essential viewing, yes, but only for buffs of either fantasy films or Old Guard Hollywood. The inconsistent special effects are the least of its problems; worse by far is what one might call presentational acting, but is in fact mostly just plain bad. Even Sabu, the Indian star who first made it big with Elephant Boy, is revealed to be a truly wooden performer. Conrad Veidt, as the cruel-as-an-adder Jaffar, comes off as a well-oiled villain, but he’s horribly miscast; he’s German through and through.

The lavish production design veers wildly between location photography, sound stage sets, and every trick in the special effects handbook, including painted backdrops, screens within screens, and all manner of superimposed images. The “cast of thousands” approach raises more questions than it was ever designed to. Was Baghdad ever this cosmopolitan? Here, every civilization in the world intermingles, the wealthy ones sporting costumes that defy rational justification. Hollywood’s arms-length, imperialistic fascination with the exotic knows no better exemplar.

The lavish production design veers wildly between location photography, sound stage sets, and every trick in the special effects handbook, including painted backdrops, screens within screens, and all manner of superimposed images. The “cast of thousands” approach raises more questions than it was ever designed to. Was Baghdad ever this cosmopolitan? Here, every civilization in the world intermingles, the wealthy ones sporting costumes that defy rational justification. Hollywood’s arms-length, imperialistic fascination with the exotic knows no better exemplar.

The Thief of Baghdad, then, forces us to ask an uncomfortable question: to whit, what allowances ought to be made for the passage of time? Some seventy-two years on, can we as contemporary viewers be reasonably expected to accept the norms and tropes of a movie so firmly rooted in the stylistic tics of its day? Let’s face it, even Casablanca is beginning to show its age, and who under, say, the age of seventy pays real attention to all but a handful of the films from Hollywood’s first Golden Age, the silent era?

Of course, The Wizard of Oz, completed only one year prior to The Thief of Baghdad, is still fresh as a daisy, easily capable of charming the socks off each succeeding generation. Why exactly it’s such a stalwart survivor is a matter for endless debate, but the bottom line is that Dorothy’s yellow-brick Odyssey is the exception, not the rule. For most art, times change, and taste changes, too.

This conundrum is hardly limited to film. Most books don’t survive for five years, much less fifty, and this is not always a question of quality. It could be bad luck, or something as simple as sentence construction. Try writing today as H.P. Lovecraft did at the peak of his powers, and you’ll have a surefire recipe for remaining unpublished. He made his mark, and deservedly so, but it’s a good thing he came up with Miskatonic U. and Cthulhu, or he’d be just as forgotten as most of his peers.

So we make allowances sometimes, yes. We have to. And we cling to what matters most in a given work’s form. Story, for example. Excellence in story-telling is what keeps Lovecraft readable and The Thief of Baghdad watchable. Superlative stories hook into our psyche in ways that even the most atrocious mistakes of acting, casting, and limited technology cannot entirely subdue.

So we make allowances sometimes, yes. We have to. And we cling to what matters most in a given work’s form. Story, for example. Excellence in story-telling is what keeps Lovecraft readable and The Thief of Baghdad watchable. Superlative stories hook into our psyche in ways that even the most atrocious mistakes of acting, casting, and limited technology cannot entirely subdue.

So despite all my niggling and disappointment, let’s not stick a fork in this particular warhorse just yet. Better to call up Netflix (or hie thee to thy local library) and rustle up a copy of The Thief of Baghdad for yourself. Press play… and see if perhaps this is one magic carpet ride that still tells a tale worth its weight in gold.

Either way, the answer, above, is C (although B, not entirely ruled out, remains under investigation).

Still one of my favorites, warts and all. Along with Fairbanks Jr.’s Sinbad the Sailor, which is currently criminally unavailable on DVD.

Poor Jaffar.

The reason the vizier in all of these movies, from here to Aladdin, always gets named Jaffar is because Jaffar was the vizier’s son, then vizier, during the time of the Golden Age of the Arabian Nights, and was a sometimes character in the tales, along with his caliph, Harun al-Rashid. Jaffar actually stars in what may be the world’s first detective story in one of those Arabian Nights stories.

In real life he seems to have been a pretty decent guy and a very hard worker, dedicated to the welfare of the caliphate. Certainly it prospered under the reins of his family, for the caliph didn’t have that much to do with day-to-day affairs. Yet because of his fame — being the only vizier whose name is actually remembered — he’s always stuck being the bad guy. It was bad enough that the caliph ended up cutting off his head. Now he’s ever and always a villain.

Howard,

I agree, poor Jaffar.

Joe: Glad to hear it passed muster despite all. I imagine the makers of the film are also happy. I met Michael Powell once upon a time…he was very old and very pleasant and a bit drenched from a NYC rainstorm…not quite as severe as what they enjoyed today and yesterday, though.

Howard: In the words of Harrison Ford, “It’s not my fault!” I’m just reporting the facts. Just the facts.

sfteory1: See above. : )

No version of The Thief of Baghdad has ever surprassed the original, silent, Doug Fairbanks version. Even when you have to take into consideration the sort of acting needed to deal with the lack of dialog.

(It’s amazing how much they can do without actually providing dialog cards.)

Yeah, I still enjoy this one. (But not Sinbad the Sailor. Sorry, Joe. Although I believe it is available as an import DVD.)

I do have a copy of Sinbad the Sailor on a DVD of dubious provenance and poor quality; I’d love (and pay money for) a legitimate, remastered release. I realize it’s also a flawed film, but hey, Fairbanks, Jr. flouncing his way across the sets, and Maureen O’Hara.

It’s also and interesting contrast with Thief of Bagdad in that I think it [Sinbad] is the least magical, special-effects-heavy Arabian Nights movie I’ve ever seen.

And yes, thumbs up to the silent version of Thief of Bagdad, although I have to be in a very particular frame of mind to watch a 140 minute silent movie.

“Of course, The Wizard of Oz, completed only one year prior to The Thief of Baghdad, is still fresh as a daisy, easily capable of charming the socks off each succeeding generation.”

Pffffft. I #$!@ing hate the Wizard of Oz. Thief of Baghdad is just fine in my book.

Mary and Joe: One of my goals in a future entry here on BG is to take a long look at the Fairbanks version.

Jeff: My memories of Sinbad (on film) seem to conflate with images of Harryhausen dinosaurs and skeleton men. I suspect that is not a good sign, either for my memory or for the many, many Sinbad adaptations. I believe Tom Baker showed up in one of them…

Andy: Fair enough––but as with Forrest Gump, which I personally loathe, society as a whole has judged otherwise. The Wizard of Oz stands on a singularly exalted pedestal. To quote the ever-bitter Mr. Vonnegut, “So it goes.”

Speaking of the silent version:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Thief-Bagdad-Achmed-Abdullah/dp/0898655234/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1351702555&sr=8-2&keywords=thief+of+bagdad+russell

I believe Tom Baker showed up in one of them…

The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. That’s the one I still watch.

When I rented this film on VHS, back in the Late Cretaceous, I came to the scene in which the benevolent supernatural dude who has the flying carpet compressed into a single sentence both a gentle refusal to lend the carpet and a complete explanation of how to steal it. My husband and I couldn’t believe that little oration. We rewound it and watched it again and again. I wrote the sentence down in my journal and returned to that page any time I needed a good laugh. Wish I knew where that volume of my journal is now.

Golden Voyage of Sinbad — yeah, that one is the best of the three, and I still have a real soft spot for it myself.