Cynthia Ward Reviews The Gods of Opar

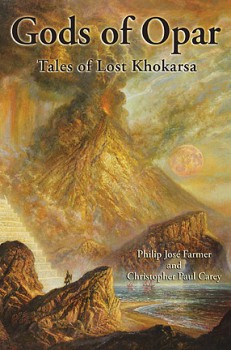

Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa

Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa

Philip José Farmer & Christopher Paul Carey

Subterranean Press (576 pp, $65.00 Limited Edition Hardcover, $45.00 Trade Edition Hardcover)

Reviewed by Cynthia Ward

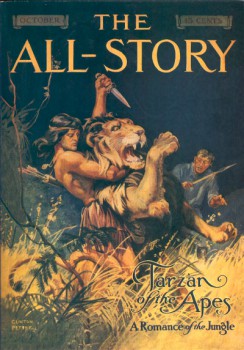

Once upon a time, in a lost civilization known as West Germany, the Kreuzberg Kaserne U.S. Army Base let fifth graders leave school grounds at lunchtime. Every week, I crossed the street to the little base bookstore. In the late winter of 1972, I bought the first DC Comics issue (#207) of “Tarzan of the Apes” because I wanted to learn how the heck a human being ended up living with apes. When the writer/artist, the late, much-lamented Joe Kubert, ended his adaptation with Edgar Rice Burroughs’s original cliffhanger, I read Burroughs’s sequel, The Return of Tarzan, to finish the origin story. Then I found myself devouring every other Burroughs book reprinted in the early 1970s.

I couldn’t have been the decade’s only new Burroughs fan, because by the mid-1970s, his estate had authorized two different Tarzan-related series by other authors: the Bunduki novels by J.T. Edson and the Ancient Opar novels by Philip José Farmer. Both series produced a novel or two and then, as far as I knew, ended. The tie-in titles went out of print, their copyright was probably owned or controlled by the Burroughs estate, and Philip José Farmer died in 2009. I figured none of these books would ever see another reprint.

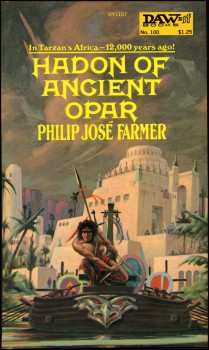

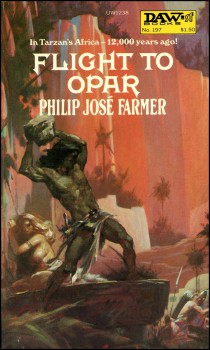

I figured wrong, because Subterranean Press has just released Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa, which is an omnibus of the two Ancient Opar novels by Philip José Farmer – Hadon of Ancient Opar (1974) and Flight to Opar (1976) – together with a third, new novel in the series, The Song of Kwasin, by Philip José Farmer and Christopher Paul Carey (Black Gate recently ran essays from Carey about the history of his remarkable collaboration with Farmer, and his discussion of Farmer’s ambitious creation, the lost civilization of Khokarsa.)

Re-reading Philip José Farmer’s Ancient Opar novels after almost forty years reveals some eye-opening contrasts, not only between the styles and approaches of Farmer and Edgar Rice Burroughs, but between the time periods in which they wrote. Not that there are no similarities. Both Burroughs’s Tarzan books and Farmer’s Ancient Opar books demonstrate no awareness that putting an essentially all-white civilization in equatorial Africa is (at best) odd. Both series feature a tall, agile, sun-bronzed, grey-eyed, black-haired archer with a scarred brow. Both series’ female characters are defined by their relationships to men. And both authors create the larger-than-life characters you expect in pulp fiction.

Re-reading Philip José Farmer’s Ancient Opar novels after almost forty years reveals some eye-opening contrasts, not only between the styles and approaches of Farmer and Edgar Rice Burroughs, but between the time periods in which they wrote. Not that there are no similarities. Both Burroughs’s Tarzan books and Farmer’s Ancient Opar books demonstrate no awareness that putting an essentially all-white civilization in equatorial Africa is (at best) odd. Both series feature a tall, agile, sun-bronzed, grey-eyed, black-haired archer with a scarred brow. Both series’ female characters are defined by their relationships to men. And both authors create the larger-than-life characters you expect in pulp fiction.

But there are significant differences between the creations of Burroughs, product of the Victorian and Edwardian Eras, and the creations of Farmer, writing during the Sexual Revolution he influenced, starting with his controversial story of human-alien love, “The Lovers” (1952). Burroughs clearly put a lot of work into his world-building, but he didn’t pay inordinate attention to contemporary knowledge — a pre-publication draft of Tarzan of the Apes mentioned tigers, a species not found in Africa, and even with that mistake corrected, his continent bears little more resemblance to the real-world Africa of his era than his canal-girdled Mars bears to the planet visited by the Curiosity rover. Meanwhile, Farmer’s two novels about the Burroughs-created civilization of Opar show an erudite knowledge of 1970s sciences, especially anthropology and linguistics. Too, Farmer’s characters are mostly respectful of their deities and belief systems, while Burroughs mercilessly satirized organized religion. And Farmer’s larger-than-life characters are, with one exception, scaled a lot closer to everyday mortals than Burroughs’s almost superheroically strong and resourceful Tarzan.

The most significant difference between the authors may be in their worldviews. Ultimately, Burroughs’s good guys are — however violent and savage–Edwardian gentlemen. They navigate a black-and-white moral universe by the compass of their strict code of honor, which includes pre-marital chastity and the always-successful defense of women’s virtue. The characters in Farmer’s Ancient Opar series inhabit a moral universe filtered through so many post-Sixties shades of gray, it’s almost misleading to label them “good guys.” Protagonist Hadon and his associates casually enjoy the premarital sex that would have been unthinkable to Edwardian readers. Hadon throws off his samurai-like warrior code when all it will do is get him killed. He and his allies fail to prevent rape. And one of his kinsmen, in Farmer’s blunt prose, “raped a priestess and killed some temple guards defending her,” then followed it up by ravaging black women (but of this, more anon).

In Burroughs’s Tarzan series, Opar is an ancient, ruined, but inhabited city in the African “jungle,” and the last surviving colony of a long-lost civilization which Tarzan suspects is Atlantean. Decades later, Farmer’s tie-in novels Hadon of Ancient Opar and Flight to Opar explore the final days of that fictional prehistoric civilization, while ditching the discredited “lost continent” of Atlantis. Instead, Farmer names this fictional civilization “Khokarsa” and locates it upon the inland seas and fertile savannahs of 10,000 BCE Africa, in what are now the Congo Basin and Sahara Desert.

You know it’s not your grandfather’s Opar from the opening of Farmer’s first tie-in novel, Hadon of Ancient Opar. For, as the eponymous protagonist departs the titular colony — the beloved home city he may never see again — he is weeping. It’s behavior unthinkable for a Burroughs hero; but do not assume Farmer’s nineteen-year-old protagonist isn’t brave, or tough, or larger-than-life. Hadon is traveling willingly to the distant Khokarsan capitol to participate in the Great Games of Klakor, which are like our Olympic Games, except the winner gets the queen along with the gold, and all the other participants end up as dead as the also-rans in The Hunger Games. Hadon employs a combination of fencing skill, wiry strength, and flexible intelligence to win both the Great Games and the hand of Awineth, High Priestess of the fertility goddess Kho and queen of the matriarchal Khokarsan Empire. However, outgoing husband Minruth, High Priest of the sun-god Resu, has no interest in giving up power; instead, he’s secretly plotting to overthrow the ancient matriarchy and become sole ruler. In service to his nefarious goal, he sends Hadon to find a woman lost somewhere in the Wild Lands of Africa — a needle-in-the-haystack quest that will take years if it succeeds, but is much more likely to get Hadon conveniently killed.

You know it’s not your grandfather’s Opar from the opening of Farmer’s first tie-in novel, Hadon of Ancient Opar. For, as the eponymous protagonist departs the titular colony — the beloved home city he may never see again — he is weeping. It’s behavior unthinkable for a Burroughs hero; but do not assume Farmer’s nineteen-year-old protagonist isn’t brave, or tough, or larger-than-life. Hadon is traveling willingly to the distant Khokarsan capitol to participate in the Great Games of Klakor, which are like our Olympic Games, except the winner gets the queen along with the gold, and all the other participants end up as dead as the also-rans in The Hunger Games. Hadon employs a combination of fencing skill, wiry strength, and flexible intelligence to win both the Great Games and the hand of Awineth, High Priestess of the fertility goddess Kho and queen of the matriarchal Khokarsan Empire. However, outgoing husband Minruth, High Priest of the sun-god Resu, has no interest in giving up power; instead, he’s secretly plotting to overthrow the ancient matriarchy and become sole ruler. In service to his nefarious goal, he sends Hadon to find a woman lost somewhere in the Wild Lands of Africa — a needle-in-the-haystack quest that will take years if it succeeds, but is much more likely to get Hadon conveniently killed.

Nowadays, such a quest is an excuse to generate somewhere between three and a dozen fantasy novels, in which the characters wander a decreasingly-interesting imaginary landscape wracked by seemingly-endless dynastic struggles. And you may be forgiven for conjuring this expectation when the excitement of the Great Games becomes enervated by the need to rush through the deaths of so many players. However, the pace picks up smartly once Hadon sets out. In fact, the pace picks up so smartly that Farmer wraps the quest up well before the end of his first book, leaving room for Hadon and his allies — who now include Hadon’s new love, Lalila; the scorned and angry queen, Aniweth; and his hated cousin, Kwasin — to undergo an enthralling series of hair-raising adventures involving prison escapes, civil war, a major volcanic eruption, and a death toll that must be in the thousands.

Hadon and company’s attempts to elude the army of the increasingly despotic and insane usurper, King Minruth, continue in the exciting sequel, Flight From Opar. In a somewhat episodic manner reminiscent of many Burroughs plots, Hadon and his allies visit a variety of increasingly desperate colonies and increasingly dangerous regions, until their much-reduced party arrives at last in Opar, and Hadon’s destiny in 10,000 BCE connects explicitly with the fate of Opar in Tarzan’s early twentieth century.

At this point, it must sound like Farmer’s Ancient Opar novels have no need for a sequel. Actually, there are enough loose ends involving secondary characters and the civil war to justify a third volume. Unfortunately, the new sequel — The Song of Kwasin, begun before Farmer’s death and completed (and largely written) by Christopher Paul Carey — is not focused on Hadon or another more-or-less admirable character. Instead, it’s centered on Kwasin, who in the earlier books served dual roles: as a larger-than-life trickster, and as a morally flexible sidekick conveniently willing to perform acts the hero can’t or won’t. However, Kwasin — who is justly hated by his cousin Hadon and the others in their party — goes beyond these well-established fictional roles. He supplements his larger-than-life warrior exploits, which would daunt even Tarzan and Conan, to engage in behavior which would have caused Conan or Tarzan to kill Kwasin. Specifically, Kwasin is a bully and a serial rapist.

At this point, it must sound like Farmer’s Ancient Opar novels have no need for a sequel. Actually, there are enough loose ends involving secondary characters and the civil war to justify a third volume. Unfortunately, the new sequel — The Song of Kwasin, begun before Farmer’s death and completed (and largely written) by Christopher Paul Carey — is not focused on Hadon or another more-or-less admirable character. Instead, it’s centered on Kwasin, who in the earlier books served dual roles: as a larger-than-life trickster, and as a morally flexible sidekick conveniently willing to perform acts the hero can’t or won’t. However, Kwasin — who is justly hated by his cousin Hadon and the others in their party — goes beyond these well-established fictional roles. He supplements his larger-than-life warrior exploits, which would daunt even Tarzan and Conan, to engage in behavior which would have caused Conan or Tarzan to kill Kwasin. Specifically, Kwasin is a bully and a serial rapist.

Of course, antiheroic traits don’t automatically make a character like Kwasin an unacceptable protagonist. However, The Song of Kwasin complicates matters by attempting to redeem Kwasin. Even the most insightful literary novel ever penned would have a hard time redeeming a bully/rapist; but this is pulp adventure fiction, a form ill-suited to such redemption. And, while Farmer and Carey wisely drop Kwasin’s racism, the collaborators regrettably uphold Kwasin’s claim (in the first Opar novel) that he never raped the “holy priestess of Kho…a teasing bitch…[who] urged me on, and then, when I had bared myself, became terrified, though I suppose I shouldn’t blame her for that.” This is the sort of blame-the-victim claim made by real-life rapists in prisons everywhere, so there’s little reason to believe Kwasin; but he undermines any remaining scrap of credibility with his description (in Hadon of Ancient Opar) of kidnapping and ravaging black women to take the edge off his horniness. So, despite the coauthors’ considerable talents and herculean efforts, I reached the end of The Song of Kwasin as I began: wishing the Khokarsans had ignored their oracle and fulfilled their law by castrating Kwasin and flinging him to the hogs.

The rapist-redemption aspect aside, Christopher Paul Carey (who apparently co-plotted with Farmer but handled the writing solo) does a fine job of extending the Burroughs/Farmer Opar franchise. He performs heroic work in simultaneously working within and expanding upon Farmer’s extensive world-building notes (a small but still-impressive number of which are appended to Gods of Opar). Carey’s prose is solid and moves the plot right along, taking as many unexpected turns as Farmer’s solo Opar novels. Carey makes the civil war and Kwasin’s experiences even more horrific than Farmer’s civil war and Hadon’s experiences. Carey even beats Farmer in his ability to create exciting combat scenes. Further, Carey (like Farmer) doesn’t fall into the Gorean trap of confusing rape with acceptable behavior. In short, it’s clear why Farmer anointed Carey to continue the Opar series. Leave Kwasin out of it and I’m willing to read more of Carey’s fiction. He’s got the talent and skills to become a Big Name.

Cynthia Ward has published fiction in Asimov’s SF Magazine and Pirates & Swashbucklers, among other anthologies and magazines. She has published nonfiction in Weird Tales and Locus Online, among other webzines and magazines. Her story “Norms,” published in Triangulation: Last Contact, made the Tangent Online Recommended Reading List for 2011. With Nisi Shawl, she coauthored Writing the Other: A Practical Approach (Aqueduct Press), which is based on their diversity writing workshop, Writing the Other: Bridging Cultural Differences for Successful Fiction.

First off, thank you, Cynthia, for your insightful review!

I have a general policy of not commenting on reviews of my work, but I feel it’s important as the coauthor of the third novel to reinforce your views on Kwasin, who indeed is an antihero and Not a Good Person. He certainly should not be regarded as someone to be admired or who has paid for his sins, despite changing as a character as the story progresses. Perhaps an afterword would have served well to explain that Phil, in his characteristically unique style, set up the character to meet his just deserts in H. Rider Haggard’s novel SHE AND ALLAN, where he is meant (by Farmer) to appear in the guise of the character Rezu, who now believes he is the sun god incarnate (the story of Haggard’s Rezu is alluded to in Minruth’s vision toward the end of THE SONG OF KWASIN). Kwasin-as-Rezu, who has become immortal by the same means as Haggard’s Ayesha, ultimately faces off against the Zulu warrior Umslopogaas and is slain by his own ax. There was a good reason Phil often referred to the character as “the ill-fated Kwasin.”

Cynthia, this morning I was lazily perusing the net when I came upon your review at Black Gate and I almost fell out of my chair upon reading the first paragraph. It brought back a lot of good memories about Burroughs and Tarzan, along with a lot of other things. Like you I spent a good portion of my childhood at that same base in Zweibrucken, West Germany.

My dad, along with me and the rest of my family, were stationed there from 1971-1974. In 1972 I was in the third grade and I pretty much haunted that same bookstore. Unlike a lot of the other bases we were stationed at, this one had the the bookstore in a separate building from the PX. I remember that it had a great comics section as well as a great selection of paperbacks. One of the first things I discovered was that Tuesday was the day that the new comics and magazines were put out. Unfortunately, since I was in the third grade at the time I couldn’t get there until after school and by then they had been picked over by the GI’s who seemed to have a huge appetite for comics. So most the cooler Marvel’s and DC’s were gone by the time I staggered in after school.

Fortunately, a friend of my Mom got a job there for awhile and she would set aside comics for me to pick up later. And along the way I discovered science fiction books and the first paperback I ever bought with my own money (Foundation by Isaac Asimov) was from that bookstore. Burroughs, Howard, Heinlein, and Tolkien soon followed. All in all I can’t help but think about that time and place without a good deal of affection and nostalgia. So thanks for a lot the review. – Randy

[…] Cynthia Ward Reviews The Gods of Opar […]

[…] Christopher Paul Carey made excellent cases here for why I should pay a lot more attention to his Gods of Opar and Tales of the Wold Newton Universe series, for […]