Spiritualism during the American Civil War

Spiritualism was well established by the time the Civil War started. As the death toll mounted — a new estimate puts the body count at 750,000 — spiritualists enjoyed ever-greater demand for their “services.”

Spiritualism was well established by the time the Civil War started. As the death toll mounted — a new estimate puts the body count at 750,000 — spiritualists enjoyed ever-greater demand for their “services.”

When you consider that the 1860 census showed only 31 million people living in the U.S., pretty much everyone had a reason to go to one. The Banner of Light newspaper ran a column with messages from dead soldiers of both armies channeled through a Mrs. J.H. Conant. One such message said,

As a favor of you today, that you will inform my father, Nathaniel Thompson of Montgomery, Alabama, if possible, of my decease. Tell him I died… eight days ago, happy and resigned.

Séances became popular with all social classes and even Abraham Lincoln attended a few hosted by the medium Nettie Colburn, a society favorite in Washington, D.C. The details of these meetings are hazy, but from what we know he went with his wife Mary Todd Lincoln, who grieved over the deaths of two of her young sons. The President may have gone along just to humor her. Apparently he found séances entertaining, once reportedly sitting on a piano with several soldiers as it levitated into the air.

It might seem strange that the President of the United States would engage in such activities, but his experiences were more the rule than the exception. Spiritualism was hugely popular with upper and middle class whites. Less is known about the working class or black experience with the Spiritualist movement during the Civil War, as there is little written record.

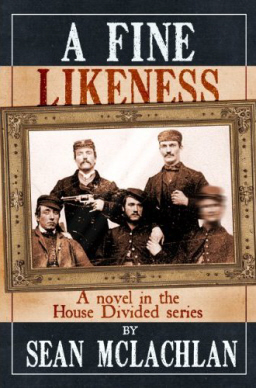

In my Civil War novel, A Fine Likeness, Union Captain Richard Addison visits a medium in order to speak to his son, who was killed at Vicksburg.

The medium’s body convulsed. His eyes rolled up, the whites glistening sickly before clenching shut. He grew stiff and lay like a board diagonally across the chair, every inch of him shaking with little tremors. Addison started leaning over to help him, but froze as Blackwood keened in a soft, plaintive voice, “Father? Are you there, Father? I can’t see you.”

Addison sank back in his chair, heart pounding. This couldn’t be… no, impossible.

“Father, is Mother there?”

The voice didn’t sound like Blackwood’s. It sounded clearer, higher, like that of a youth. And there was no trace of an English accent. He talked like a Missouri boy.

“Father? Can you hear me?”

“Mother isn’t here. She’s in St. Louis,” Addison replied with a mixture of hope and embarrassment. Who was he talking to?

“Don’t mourn me, father. I’m at peace.”

“Nathan?”

Blackwood couldn’t be faking this, could he?

“Freespirit is with me,” the voice said, and Addison’s throat clenched. “Remember how we used to go riding together? He was killed by that same cannon ball.”

“Nathan! Oh God, my son!”

“It didn’t hurt, Father. We’re together in the afterworld. Don’t mourn us. We will wait for you and we’ll race and jump again.”

Through eyes blurred with tears Addison noticed a hazy light appear above Blackwood’s head. He wiped his eyes and blinked, and his body went cold.

Wavering in the air was Nathan. He looked all gray and white, blurry and distorted, but there was no mistaking. Nathan stared straight ahead, wearing his cavalryman’s uniform.

“Nathan!” Addison gasped. “I see you! Can you see me?”

“Yes, Father. You look well. I have a message for Mother.”

Addison didn’t respond. He stared at Nathan’s shade, a memory nagging at his mind as he tried to make out something that rested on his son’s left shoulder, something pale and flat that curved over the collar. The vision was so blurry and distorted he couldn’t quite make it out, but it looked like. . .

… a hand.

His hand.

Addison leapt from his seat and the chair clattered across the floor. Nathan’s image blotted out. Blackwood jerked and opened one eye. Addison’s gazed flicked to every corner of the room.

Right behind him, a light shone through a hole in the crêpe.

Addison tore down the gauze and behind it saw a curved mirror affixed to the wall. Beneath it stood an oil lamp, and beside it, half covered with black cloth, lay a tintype of Nathan. He yanked the cloth away and saw his own image. It was a photograph taken just before Nathan’s regiment headed east, father and son posing in Jameson’s Photographic Studio not five blocks from where he stood. The photograph Mary thought she’d lost.

He spun around. Blackwood shrank back in his seat, hands outstretched before him.

“Wait, I can explain!”

Addison strode across the room and rammed his fist into the Englishman’s face, knocking him to the floor. He drew his pistol, planted a knee on Blackwood’s chest, and shoved the barrel against his forehead.

While this séance ended badly for the medium, his profession saw good times during the Civil War. Spiritualism emerged in the late 1840s, finding its first stars in the Fox sisters, three young women who “talked” to disembodied spirits through rapping noises. They became hugely popular and encouraged a small army of imitators. The Fox sisters’ first audience was among the Quaker community, where they had many friends, so from the start spiritualism was connected with progressive ideas such as abolition, temperance, and women’s rights. Spiritualist philosophy stated that the cosmos was so interconnected that serious injustices were an injury to all.

While the movement was most popular in the New England and mid-Atlantic states, mediums could be found in all parts of the country. Newspapers such as the Spiritual Telegraph and Banner of Light gained national circulation.

Visitors to a séance could expect quite a show. Spirits would announce themselves with rapping and clicking noises, answering questions through code. Sometimes trumpets and drums would float through the room and play themselves, and ghostly images of the spirits themselves would appear. Spiritualists would also engage in automatic writing and painting to transmit messages and images from the Other Side.

It’s difficult to estimate how many people believed in these performances. Some scoffed at them or went purely for their entertainment value, while others became true believers. Perhaps most of the audience lay somewhere in between, unsure what they were seeing, but wanting to believe in the reassuring messages they heard from dead relatives.

The majority of mediums were women. Spiritualism was, in fact, the first American religious movement to encourage women to be religious leaders, giving them a rare chance to have a voice in society. The Spiritualist movement was individualistic, there was no hierarchy or official canon, and this allowed women a chance to express their opinions through the spirits. They could even give public lectures to mixed audiences, something that had been all but unheard of before this time.

During the war, a new tool was added to the medium’s bag of tricks. A photographer named William Mumler began to create “spirit photographs” that showed people with ghostly figures of the dead.

While they are obvious double exposures to the modern eye, photography was still in its early days and many were fooled. Mumler’s most famous photograph was actually taken after the war and shows Mary Todd Lincoln with the spirit of Abraham Lincoln hovering over her.

Mumler’s photographs were very lucrative and other photographers were soon following his lead. As the Illustrated Photographer magazine quipped in 1869, “who could expect spirits to be called ‘from the vasty deep’ for less than ten dollars per head?” This at a time when a private in the Union army earned $13 per month!

Some were skeptical, including P.T. Barnum. Despite having coined the term “there’s a sucker born every minute,” Barnum had his limits and felt Mumler had gone too far.

In 1869 Mumler was brought to trial for fraud. He was also accused of breaking into people’s homes to steal photos of dead relatives, which he would then use for his “spirit photographs.”

To prove how easy it was to create one of these ghostly images, Barnum had himself photographed with the spirit of the dead president. The charges were eventually dropped, but Mumler was ruined by the scandal and died in poverty.

After the war, the boom in spiritualism continued. Stable conditions and a rapidly expanding railway system helped famous mediums do nationwide tours. The massive numbers of war dead left millions of people desperate for a message from beyond.

It was not to last. In 1888, the New York World paid Margaret Fox $1,500 to reveal how she faked the rapping noises. The Fox sisters died a few years later in poverty. The Spiritualist movement began to fade, although it never completely died out.

Sean worked for ten years as an archaeologist in Israel, Cyprus, Bulgaria, and the U.S. before becoming a full-time writer specializing in history and travel. He’s the author of numerous history books on the Middle Ages, the Civil War, and the Wild West. He is also the author of A Fine Likeness, a horror novel set in Civil War Missouri, and The Night the Nazis Came to Dinner and other dark tales. Visit him online at Civil War Horror.

There was a big resurgence in Spiritualism in London during the Second World War, especially right after the Battle of Britain, for a lot of the same reasons it took off in the US during the Civil War. In a long-ago other life–okay, the 1990s–I wrote a dissertation chapter about a major poet’s unpublished and unpublishable Spiritualist novels, most of which were the result of spending the awful nights of the Blitz huddled around a seance table.

Your book sounds intriguing. Thank you for a wonderful post.

[…] Spiritualism During the American Civil War […]