Genre 2012: the Ghetto Remains the Same?

Pssst. Hey, buddy. Yeah, you. Come over here a sec. Listen. Did you know that by virtue of reading this, by virtue of even cruising this site, you live in a ghetto?

Pssst. Hey, buddy. Yeah, you. Come over here a sec. Listen. Did you know that by virtue of reading this, by virtue of even cruising this site, you live in a ghetto?

It’s true.

Let me explain.

Once upon a distressingly long time ago, when I worked in retail bookstores, life was peaceful. Organized. Every book had its place. Each, by its nature, described in advance its own prized spot on the shelf. Controversy in the rarefied field of what we bibliophiles archly referred to as Incoming Tome Location had been all but eradicated.

There was, of course, one pesky exception. Genre. Or, to be exact, Genre Fiction. The breakouts for Romance and Mystery/Suspense were generally simple enough, a Maginot Line easily upheld, but woe betided Fantasy and Science Fiction (not to mention everyone’s favorite red-headed stepchild, Horror, the shelves for which invariably faced into an out-of-the-way corner, as if they attracted only trench-coated perverts and budding psychopaths). Garcia Marquez and Italo Calvino were literature, and clearly so, by virtue of being international in stature. But then, what of Stanislaw Lem? How had he become marooned in Sci-Fi? Maybe, we clerks said, speaking in clandestine whispers lest our overlords hear us, Lem’s titles could be cross-shelved. Shelved, God forbid, in more than one place.

Cross-shelving: the very idea hinted of radicalism too profane to countenance. For merely thinking it, we could be fired. For actually implementing it, on the sly, we could be branded, tarred and feathered, then sentenced to read (for eternity) only Idiot’s Guides and self-help dieting books.

In the end, we let management win. The books stayed where they were, where they were “supposed to be.” Michael Moorcock in fantasy, and Wilkie Collins in literature. The ghosts of Toni Morrison would never have to suffer the ignominy of sitting with Mssrs. King and Lumley on the Horror shelves, although they might, depending on the bookshop, have to haunt the shelves of African-American Fiction.

And then a strange thing happened. The chain bookstores, victims of digital portability and our ongoing national experiment in adult Attention Deficit Disorder, imploded. Crown closed. So did Little Professor and B. Dalton. Waldenbooks and Brentano’s merged with Borders, which in forgetting it had been birthed as an exotic special event, tried to go worldwide and went belly-up instead. Commerce, too, suffers mass extinctions.

Thrillingly, a few stalwart independents remain (along with a depressingly streamlined version of Barnes and Noble), and in these local, cramped, labor-of-love shops, a glorious slippage rears its head. Books, in certain quarters, are shelved according to personal taste.

Great Scott, bring on the firing squads.

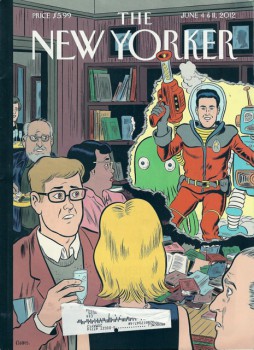

Twenty years ago, The New York Times review of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars felt almost obligated to write that the book contained “characters as richly drawn as any in conventional fiction,” as if that were somehow entirely beyond the pale and possibly against the law (Red Mars went on to win the ’93 Nebula). But times change. This past June, the Times’s cross-town partner in cultural watch-dogism, The New Yorker, released “The Science Fiction Issue,” in which some eighty percent of the magazine was devoted to writings on the state of Sci-Fi. Contributors included Ursula K. Le Guin, China Miéville, Karen Russell, and Ray Bradbury (although the latter sadly did not live to see the issue reach print). Jonathan Lethem, whose work deliberately slides between fictional forms––and very likely cross-shelves his own titles whenever he enters a bookstore––pops up with an essay, and Jennifer (Pulitzer) Egan adds to A Visit From the Goon Squad with a futuristic tale of high-tech, low-sex espionage, “Black Box,” a story constructed (and initially broadcast) as a series of tweets.

Twenty years ago, The New York Times review of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Red Mars felt almost obligated to write that the book contained “characters as richly drawn as any in conventional fiction,” as if that were somehow entirely beyond the pale and possibly against the law (Red Mars went on to win the ’93 Nebula). But times change. This past June, the Times’s cross-town partner in cultural watch-dogism, The New Yorker, released “The Science Fiction Issue,” in which some eighty percent of the magazine was devoted to writings on the state of Sci-Fi. Contributors included Ursula K. Le Guin, China Miéville, Karen Russell, and Ray Bradbury (although the latter sadly did not live to see the issue reach print). Jonathan Lethem, whose work deliberately slides between fictional forms––and very likely cross-shelves his own titles whenever he enters a bookstore––pops up with an essay, and Jennifer (Pulitzer) Egan adds to A Visit From the Goon Squad with a futuristic tale of high-tech, low-sex espionage, “Black Box,” a story constructed (and initially broadcast) as a series of tweets.

“The Science Fiction Issue,” at least between the confines of its papery covers, comes across as a fabulous example of cross-shelving in and of itself. In book form, William Gibson may never be filed under anything but Science Fiction, but in these pages, he sits alongside Anthony Burgess, whose philosophical 1973 reprint manages to cover a large chunk of Catholic Church doctrine while detailing his disgust at the fate of his Clockwork Orange anti-hero, Alex. Did the box-style bookstores ever file Burgess under anything other than literature? Never. Nor would they now, were they still alive today.

The New Yorker’s late but welcome embrace of Science Fiction does not come free of hazards. The very fact that the issue had to be titled “The Science Fiction Issue” is itself troubling; surely true acceptance would imply that prose pieces devoted to technological “what ifs” could slip neatly, naturally, into any of The New Yorker’s fifty-some annual issues. But perhaps that time is now not so far away.

Le Guin’s entry takes that exact if optimistic position. She writes that over the last century or so, critics and academicians tended to stick Science Fiction writers (and readers) in a literary “ghetto.” She further claims that Sci-Fi writers were complicit in accepting this ghetto, and did so because ghettos, “like all gated communities, give the illusion of safety.” Two-thirds of her article, however, indulges in what she labels “ghetto nostalgia”––arch gossip from the fifties, heady reportage on genre’s best insider skirmishes––and she’s free to do so because, she claims, the ghetto is now largely gone.

Le Guin’s entry takes that exact if optimistic position. She writes that over the last century or so, critics and academicians tended to stick Science Fiction writers (and readers) in a literary “ghetto.” She further claims that Sci-Fi writers were complicit in accepting this ghetto, and did so because ghettos, “like all gated communities, give the illusion of safety.” Two-thirds of her article, however, indulges in what she labels “ghetto nostalgia”––arch gossip from the fifties, heady reportage on genre’s best insider skirmishes––and she’s free to do so because, she claims, the ghetto is now largely gone.

But can Le Guin possibly be serious? Digital culture, which plays its ongoing part to demolish the barricades of literary difference, does perhaps add some shine to her argument. To shop Amazon or similar on-line retailers is not to shop by genre, but by association. In selecting Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness on Amazon, one quickly discovers that customers who purchased that title also bought Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother, and (surprised drumroll, please) Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. By clicking on the Gilman title, Amazon links to Marge Piercy, and from Piercy it’s only a hop, skip and a jump to the New Age tropes of Starhawk. New Age, of course, lives in its own bookstore ghetto and rarely if ever escapes, although Richard Bach (Jonathan Livingston Seagull), who was once in a writing group with Bradbury, soars onward as an obvious exception.

Ryan Britt, writing for Tor.com, notes that the actual fiction contained in The New Yorker’s Sci-Fi outing is drawn from writers whose flag is planted chiefly in the literary camp: Egan, Lethem, Junot Diaz, and Sam Lipsyte. (Lethem would likely argue the point; he was up for a Nebula Award in 2001.) Britt’s observation is correct enough, but surely if the ghetto walls have really been thrown down, then should this matter? Britt proceeds to ask why The New Yorker didn’t solicit fiction, instead of an essay, from Miéville. Not a bad question, but he might equally well ask its opposite, to whit, what if the ever iconoclastic Miéville hopped the ghetto himself (as he metaphorically does in The City and the City) and sent a story bereft of all speculative elements to, say, Granta or The Iowa Review? Better yet, what if he submitted under a pseudonym, so no associations with his name could be made? What if his story were then published, and hailed for its remarkable, idiosyncratic style? Would Miéville then be “taken seriously” as a writer? Would he at last be annointed as appropriate New Yorker fare?

Le Guin may or may not side with Pollyanna in her assessment of where Science Fiction now sits at the table, but clearly outright Fantasy (or worse, Fantasy Adventure) is not welcome at all––unless, perhaps, it’s under the table, where it might usefully gnaw up scraps. Or in Young Adult, where lightning thieves, Quidditch practitioners, and Sword & Sorcery are now well and truly entrenched. Of course youth, as we know, is wasted on the young. Surely the titles filed therein (alongside Lord Of the Flies and The Pigman) can’t be serious books?

Le Guin may or may not side with Pollyanna in her assessment of where Science Fiction now sits at the table, but clearly outright Fantasy (or worse, Fantasy Adventure) is not welcome at all––unless, perhaps, it’s under the table, where it might usefully gnaw up scraps. Or in Young Adult, where lightning thieves, Quidditch practitioners, and Sword & Sorcery are now well and truly entrenched. Of course youth, as we know, is wasted on the young. Surely the titles filed therein (alongside Lord Of the Flies and The Pigman) can’t be serious books?

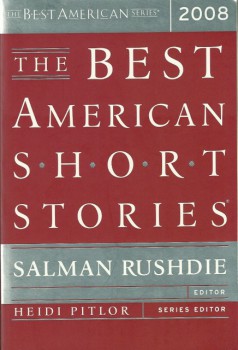

Karen Russell, for one, isn’t buying that argument. Her New Yorker entry cheerfully claims that Terry Brooks’ Swords of Shannara is a better book than Pride and Prejudice. “In the dead of night,” Russell advises, “keep reading Terry Brooks until you’re out of books.” But one of Russell’s great successes was a short first printed in Zoetrope, “Vampires in the Lemon Grove,” a story anthologized the next year in both Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror Volume XXI and, more “importantly,” in Best American Short Stories 2008. Who would she rather have as an ideal reader, Terry Brooks or Jane Austen? Perhaps more to the point, all hail Zoetrope for seeing through the forest of labels and flak and simply taking the story on its own merits: as a good piece of writing.

Forbes’ latest list of top-grossing authors suggests the book-buying public is on Zoetrope‘s side (either that, or a sizable chunk of those still literate enough to read books are fantasy enthusiasts). In the top fifteen grossing authors of 2011, we find Stephen King, J.K. Rowling, Suzanne Collins, Dean Koontz, Stephanie Meyer, Rick Riordan, and (gasp) George R.R. Martin.

Adventure Fiction, Fantasy, Science Fiction, Literary Fiction––these are all legitimately descriptive labels, but they are also self-limiting, appended after a work’s creation in order to sub-divide and classify published writing for the sake of one thing: marketing. Supposedly, fiction’s various divisions promote sales. They also prevent publication. In 2009, I won the First Coast Novel contest with A Most Unruly Gnome, a “literary fantasy” featuring ambient statuary, outright adventure, and an exploration of nationalism. Neither of the final judges, novelists Lenore Hart and David Poyer, are fantasists themselves; their work appears in the Literature section of your local shop. Happily, A Most Unruly Gnome did win me an agent, but selling my manuscript has proven to be an uphill climb. Nobody, my agent reports, knows where such a work ought to sit on the bookstore shelves.

My old bookstore mates and I hear such stories and we sadly shake our heads. We know the truth: that genre labels are a fine starting place both for choosing what to read and for allocating space on a bookshelf, but they are only a start, and reading, the event of a lifetime, is a long-distance race. We must dare, in our minds and in our reading choices, to cross-shelve continually, to endlessly mix and match, and we must do so with the same fierce attention we give to all those other essential life pursuits, including but not limited to dating, sex, raising children, and tending to those who, through no fault of their own, have grown old.

New walls will always be built, of course. But it’s up to us, savvy and courageous readers that we are, to hack our way out of the ghetto, and to throw those great walls down wherever we may find them.

Excellent – but I feel compelled to let you know that my local bookstore shelved A Clockwork Orange in the science fiction and fantasy section of the store – and that was back in the early 70s.

Considering that the manager introduced me to a lot of good SF, I think this incident represents an outlier – the “exception that proves your rule”, rather than a chink in the armor of your thesis. I strongly suspect that the manager was a clandestine inhabitant of the ghetto and used her privileged position to try and breech the walls a bit.

Pre-internet (pre cellphone and ubiquitous cable) it was a lot harder for your average citizen to report such malfeasance to corporate headquarters….

Stealth cross-shelving seems to be an increasingly common customer behavior. It’s not unusual to see Neo-Pagans moving Starhawk’s books from the New Age section to the Religion section.

I’ve also seen patrons of B&N reorganize a shelf so that a book by an author they favor can face cover-out. I myself moved one of the copies of James Enge’s A Guile of Dragons from the alphabetical shelves in the SF/F section to the New Releases shelf. There was a big empty spot nobody was using, so it harmed no one.

Sarah: Yes, I’ve seen customers rearrange shelves to their taste, as well––and good for you for doing it yourself, as I have, too––anarchy has its place, yes? But what I have never seen are customers toting books from one aisle to another, from one shelf to another. I didn’t write this piece to inspire such behavior, but one wonders if that might be the logical upshot.

Also: A friend who edits a literary magazine read this essay and sent me a comment (over Facebook, no less, proving not only that I dabble in the arcane and suspect, but so do the editors of literary magazines). His view is that once all things print have been reduced to eBooks, the ghetto will vanish for good, since no one, at a glance, will be able to tell what anyone else is reading. Austen or Disch, to use his examples: who can tell the difference from the far side of a Kindle?

Another friend (over email, this time), noted that “new release” tables in bookstores host all manner of genres all together. He is correct, of course, but here’s how those tables work: they are purchased space. Publishers BUY those spots to promote new titles, or, occasionally, anything else they think is on the boil. The system works, too––or at least that’s what I learned at Borders. Books on those tables sell better than books in their proper shelf sections. Seems to me that this suggests cross-shelving and shopping/reading by association is actually desirable and effective.

Not that it would ever work store (or library) wide. That would be chaos.

Anarchy.

Bad?

: )

I’m sure that what I say is not very original. What about trying to promote a new “genre” called something like “crossover literary fiction”? (it’s probably been tried?). Perhaps the reason that it’s difficult to find a genre, or even an audience for some works is that one has to tell the reading or watching public up front what they’re getting. Maybe if the TV series “Firefly” had spent more time promoting itself as a crossover western/sci-fi epic, people would have had different expectations when they watched? I think a lot of people read books like a lot of people eat, they want comfort food, without surprises. So if you tell them up front what’s in it, by giving it a label that tells readers it’s a fantasy/thriller maybe that would that help? Could on-line book sellers be convinced to start a new genre label, called “mash ups” or the above “crossover literary fiction” and have a short explanation of what it is?

I really think this approach would work, which probably means it’s doomed. More and more crossovers are happening in visual media. Look at “Life on Mars” the time travel policy story set in the 70s, and even MIB. And “Grimm” and “Once Upon a Time”. Dr. Who (not that I watch that) just had a crossover western with a cyborg bounty hunter. In books, look at the Dan Brown books or Preston-Child stuff; these got placed in the Thriller genre, but to me, they are mash-ups with a detective like foundation mixed with fantasy, horror, and science fiction. Or all the Vampire/teen romance stuff- which has become it’s own genre almost.

Wasn’t there a book out a few years ago about an animate teddy bear that could make everyone feel their deepest childhood desires? Didn’t that one have a SWAT team scene in it? What about a new genre section, oh, wait, what about a literary prize section? Surely that would entice readers. One still has to be carefull to explain that these books are not “comfort food” and can’t be easily categorized. “Rigney’s work, which defies categorization, uses a fantasy setting to explore terrorism and nationalism, seen through the eyes of what are normally inanimate objects, but because we created them, may themselves reflect the human condition”. How about something like that? Or is that too “book-jackety”?

I think publishing houses and editors are missing some obvious trends, so perhaps those of us who like more of a mash-up genre need to lead it into internet publishing, and get it popular enough that the established publishing houses want in. There’s got to be some opportunity or way to do this.

By being so conservative, publishing houses are missing opportunities. Where’s the proverbial “stealth operations” side of a publishing house that’s trying to find/generate the latest trends in literary works? Just sitting around waiting for people to write things that fit into established genres is a business strategy that easily risks being upended by someone. Everything is about innovation these days. Just making more police procedurals, for example, isn’t going to last as a way to sell books. We’ve all read the Swedish police procedurals now, what are we to do, move on to the next country? Boring. I know nothing of this industry so I merely muse in the dark, with oven mitts.

After the novelty wore off, I’m not sure I’d like a bookstore without genres. If everything was on shelves by author name in alphabetical order and that’s it, well, I’m sure I’d read some things I wouldn’t normally. But, sometimes I just want a science fiction story with space battles, and I don’t want to search through an entire book store to find it. Genres provide some sort of needed foundation, but have become straight-jackets.

Science fiction is breaking out of its genre prison more quickly than fantasy simply because we are starting to live in the worlds dreamed up by science fiction writers.

[…] Genre 2012: The Ghetto Remains the Same […]

[…] Possibly yes, possibly no, but clearly that equation is messy at best, since both Shimmer and Black Gate are nominally genre markets. (For more musings of mine about the divides between literary and genre fictions, please visit my previous Black Gate post, “The Ghetto Remains the Same.”) […]