Romanticism and Fantasy: William Wordsworth, Part Two — The Prelude

This post is part of an ongoing series about fantasy and the literary movement called Romanticism, specifically, English Romanticism in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The series began with this introductory post, continued with an overview of the neo-classical eighteenth century that the Romantics revolted against, considered the Romantic themes in English writing from 1760 to about 1790, then looked at elements of fantasy and Romanticism in France and Germany before returning to England to consider the Gothic. I wrote about the work of William Blake here, and last time I began a consideration of fantasy elements in the work of William Wordsworth.

This post is part of an ongoing series about fantasy and the literary movement called Romanticism, specifically, English Romanticism in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The series began with this introductory post, continued with an overview of the neo-classical eighteenth century that the Romantics revolted against, considered the Romantic themes in English writing from 1760 to about 1790, then looked at elements of fantasy and Romanticism in France and Germany before returning to England to consider the Gothic. I wrote about the work of William Blake here, and last time I began a consideration of fantasy elements in the work of William Wordsworth.

As I said then, Wordsworth is not a writer with many overt fantastic elements in his major works. Still, I find there’s a fantastic feel that emerges from the use of certain structures and imagery. Comparing his work to the motifs of fantasy fiction in Clute and Grant’s Encyclopedia of Fantasy, I found parallels between his use of nature and the way “the Land” has been imagined in secondary-world fantasy. The notion of “thinning,” the fading of enchantment and meaning, seems to resonate with Wordsworth’s poetry as well.

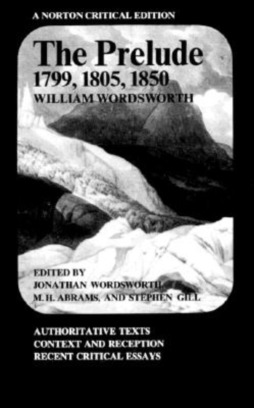

Bearing all this in mind, I want to look here at perhaps Wordsworth’s greatest accomplishment, The Prelude, his epic poem on the growth of his own mind. Before doing that, though, I want to introduce some more concepts from the Encyclopedia of Fantasy, and then bring in some ideas from M.H. Abrams’ excellent critical study of Romanticism, Natural Supernaturalism. And with all that will come some ideas from J.R.R. Tolkien.

Clute and Grant, in their definition of “fantasy,” argue that “the greatest fantasy writers … almost invariably engage deeply with the transformative potentials of fantasy.” More specifically: “A fantasy text may be described as the story of an earned passage from bondage — via a central recognition of what has been revealed and of what is about to happen, and which may involve a profound metamorphosis of protagonist or world (or both) — into the eucatastrophe, where marriages may occur, just governance fertilize the barren land, and there is a healing.”

Clute and Grant, in their definition of “fantasy,” argue that “the greatest fantasy writers … almost invariably engage deeply with the transformative potentials of fantasy.” More specifically: “A fantasy text may be described as the story of an earned passage from bondage — via a central recognition of what has been revealed and of what is about to happen, and which may involve a profound metamorphosis of protagonist or world (or both) — into the eucatastrophe, where marriages may occur, just governance fertilize the barren land, and there is a healing.”

I think this sequence is, as a structure, not unique to fantasy. Imagine it as a pattern of (implied) Golden Age, then Fall, then Redemption and/or Apocalypse; phrased that way, it’s the pattern of the Christian Bible, from Genesis to Revelations. You can see it as well in the round of the seasons (starting with summer and ending with spring); you can see it in the pattern of human aging, from juvenile innocence, to adolescent or post-adolescent alienated experience, to a mature harmonising of both. You can see it as Beginning, Middle, and End. The point is that it’s a primal, mythic pattern. And it seems to me that it’s also a structure to a large extent implicitly present in Wordsworth, especially in The Prelude.

M.H. Abrams, in Natural Supernaturalism, suggested that the Romantics generally, with Wordsworth a prominent example, displaced or secularized “inherited theological ideas and ways of thinking.” For Abrams, in fact, many Romantics “undertook, either in epic or some other major genre — in drama, in prose romance, or in the visionary ‘greater Ode’ — radically to recast, into terms appropriate to the historical and intellectual circumstances of their own age, the Christian pattern of the fall, the redemption, and the emergence of a new earth which will constitute a restored paradise.” That pattern of fall, redemption, and apocalypse is at the very least close to the pattern Clute and Grant identify in fantasy; I note that Abrams finds a symbolic marriage frequently used as an image of the renewal brought by apocalypse, just as Clute and Grant identify marriage as an often-used element of the conclusion of fantasy stories, when the world has been healed.

In the Book of Revelations — the last book of the Bible — the making of a new heaven and a new earth are prophesied. For Abrams, many major Romantic works conclude with a similar radical remaking of the world. All things become new. Sometimes that apocalypse is literal and external, sometimes internal and spiritual. In both cases, it often follows from some kind of literal or metaphorical quest, yet it also may be sudden, even unearned; Abrams describes the Christian interpretation of history as “right-angled,” by which he means “the key events are abrupt, cataclysmic, and make a drastic, even an absolute, difference.” The advent of the apocalypse is one such event. It is an unexpected happy ending. In terms of fantasy, or fairy-story, it is Tolkien’s eucatastrophe.

In the Book of Revelations — the last book of the Bible — the making of a new heaven and a new earth are prophesied. For Abrams, many major Romantic works conclude with a similar radical remaking of the world. All things become new. Sometimes that apocalypse is literal and external, sometimes internal and spiritual. In both cases, it often follows from some kind of literal or metaphorical quest, yet it also may be sudden, even unearned; Abrams describes the Christian interpretation of history as “right-angled,” by which he means “the key events are abrupt, cataclysmic, and make a drastic, even an absolute, difference.” The advent of the apocalypse is one such event. It is an unexpected happy ending. In terms of fantasy, or fairy-story, it is Tolkien’s eucatastrophe.

One must be careful here. Tolkien identified the birth of Christ as “the eucatastrophe of Man’s history.” And: “The Resurrection is the eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation.” To the extent that I understand his term, it seems to me that the apocalypse is the eucatastrophe of the Christian Bible as a whole unit. Tolkien said (in his essay “On Fairy-Stories”) of the eucatastrophe that it “is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur … it denies … universal final defeat and in so far is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.” The Christian Apocalypse depicted in the Book of Revelations would of course be something more permanent than this; what I want to argue is that when the apocalypse is displaced onto the natural world, as the Romantics frequently did, apocalypse becomes eucatastrophe — the conclusion, as Clute describes it, of much fantasy.

In that context, it’s interesting to me that Tolkien uses the word “Joy” so prominently in his definition of ‘eucatastrophe.’ That word Joy returns us to the Romantics. For Abrams, joy, whether in Wordsworth or in, for example, Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” (used as the lyrics for Beehoven’s Ninth Symphony), is to the Romantics “the sign in our consciousness of the free play of our vital powers.” It is what one feels when one’s visionary capabilities are at their height. If one associates it with the eucatastrophic, or apocalyptic, emotion that Tolkien describes, then it’s no surprise to read that, for example, Blake’s Orc, so very different from Tolkien’s creatures, seeks “the renewal of fiery joy.” It may be a coincidence, in that Tolkien almost certainly was not thinking of Blake or the Romantics when he used the word, but it also might be a sign that he is in fact talking about the same feeling.

(Tolkien, so far as I know, had no particular interest in the Romantics. They were well after the periods of literature that held the most fascination for him. But it is interesting, after reading the Immortality Ode, to find Tolkien speaking of the eucatastrophe reflecting “a glory backward.” Given Wordsworth’s use of the image, it’s another resonant verbal coincidence.)

(Tolkien, so far as I know, had no particular interest in the Romantics. They were well after the periods of literature that held the most fascination for him. But it is interesting, after reading the Immortality Ode, to find Tolkien speaking of the eucatastrophe reflecting “a glory backward.” Given Wordsworth’s use of the image, it’s another resonant verbal coincidence.)

Now, Clute and Grant have an entry on “apocalypse,” but describe it mainly as a source of imagery deriving from the Biblical text, or as something to be averted so a secondary world can be saved. What I want to establish here is that an apocalypse is often the way by which a world is transformed. If, as Clute and Grant suggest, many fantasy narratives are about averting that complete transformation, still it is also true that radical fantasy, the fantasy of the Romantics, embraces the reinvention of the world — whether in a literal form or not.

An apocalypse is not necessarily an external event. Abrams describes a tradition of Christian writing, starting with Augustine’s Confessions, which displace the shape of Christian history onto the events of a single life. For Abrams, Wordsworth’s “Prospectus” to The Recluse (the greater never-written epic to which The Prelude was to be, literally, the prelude), written after The Prelude was largely completed, follows in that tradition, firmly shifting the apocalypse which Wordsworth will depict to the inward realm. It certainly explicitly shuns the overtly fantastic or spectacular:

Jehovah — with his thunder, and the choir

Of shouting Angels, and the empyreal thrones,

I pass them, unalarmed. Not Chaos, not

The darkest pit of lowest Erebus,

Nor aught of blinder vacancy — scooped out

By help of dreams, can breed such fear and awe

As fall upon us often when we look

Into our Minds, into the Mind of Man,

My haunt, and the main region of my Song.

— Beauty — a living Presence of the earth,

Surpassing the most fair ideal Forms

Which craft of delicate Spirits hath composed

From earth’s materials — waits upon my steps ;

Pitches her tents before me as I move,

An hourly neighbour. Paradise, and groves

Elysian, Fortunate Fields — like those of old

Sought in the Atlantic Main, why should they be

A history only of departed things,

Or a mere fiction of what never was?

For the discerning intellect of Man,

When wedded to this goodly universe

In love and holy passion, shall find these

A simple produce of the common day.

— I, long before the blissful hour arrives.

Would chaunt, in lonely peace, the spousal verse

Of this great consummation : — and, by words

Which speak of nothing more than what we are.

Would I arouse the sensual from their sleep

Of Death, and win the vacant and the vain

To noble raptures[.]

So: Wordsworth will pass by traditional ideas of God, will pass by pagan myth, and will locate real awe in “the mind of Man.” Utopia will be built in this world; this world, the “simple produce of the common day,” will have the joy of an otherworldly afterlife. This will be a “spousal verse,” a marriage song; again, marriage symbolism is associated with apocalypse. And so the sensual will be awoken from their sleep of death by this great song.

William Blake, who generally respected Wordsworth as one of the greatest living poets, claimed to a friend that reading the “Prospectus” gave him “a bowel complaint that nearly killed him.” Personally I find it an odd mixture of rhetoric, combining the traditional epic poet’s invocation of the muse, the stance of a prophet promising an awakening to come, and a realist writer’s praise of the common day. How does it all cohere? How could Wordsworth think that his promise to depict reality, however heightened, could plausibly lead to the sort of apocalypse that will “arouse the sensual from their sleep / Of Death”?

William Blake, who generally respected Wordsworth as one of the greatest living poets, claimed to a friend that reading the “Prospectus” gave him “a bowel complaint that nearly killed him.” Personally I find it an odd mixture of rhetoric, combining the traditional epic poet’s invocation of the muse, the stance of a prophet promising an awakening to come, and a realist writer’s praise of the common day. How does it all cohere? How could Wordsworth think that his promise to depict reality, however heightened, could plausibly lead to the sort of apocalypse that will “arouse the sensual from their sleep / Of Death”?

Abrams argues that Wordsworth’s claim here fits, perhaps unknowingly, into a specific philosophical tradition. This tradition identifies God as the source of creation, and the Fall as a collapse into multiplicity; it runs from Neoplatonism through Hermetic philosophers up to the German mystic Jacob Boehme and beyond. Boehme was a significant influence on Blake, and an even greater influence on the post-Kantian idealist philosophers that Coleridge and Wordsworth went to Germany to study in 1798. Wordsworth ultimately did not in fact study them as Coleridge did, but for Abrams their work suggests “a general tendency of thought” during the age.

The tradition, or myth, suggests that there was a primal all-creative unity, which by its nature created multiplicity, its own contraries — thus establishing a Fall into the division of subject and object. That process continues, elements multiply, the world expands, and conscious thought reflecting on the world helps sharpen that original divide of subject and object, self and other. Our own reasoning emphasises our division from the world around us, causing greater fragmentation. But, by the nature of the process, eventually the whole thing reaches an apex of generation, at which point it turns again toward reunification. That is the nature of nature: it will lead back, not to the same unity with which all things began, but a greater, more mature unity in which all the multiple terms that make up the diverse world have been integrated into a whole. That final reunification is the symbolic apocalypse Wordsworth promises to bring, if only in the minds of his readers. Schelling, one of the philosophers who presented this myth, seems to have believed that a poet-prophet might appear to heal the division of man and nature: “Perhaps he will yet come who is to sing the greatest heroic poem, comprehending in spirit what was, what is, what will be, the kind of poem attributed to the seers of yore.” So Wordsworth, who will awaken the sensual from the sleep of death. The structure of this Neoplatonist myth underlies the Immortality Ode and “Tintern Abbey,” and the “Prospectus” suggests it is what would have come in The Recluse. The whole thing was never written, but it still informs the portion he did write, The Prelude.

Fall, redemption, apocalypse; and all things are made new. As Abrams points out, Romantic philosophy and poetry have isolated a mythic structure, and are retelling it in new terms, without reference to Christian mythic ideas. Rather than Christ or God stepping in to turn the Fall around and lead ultimately to a divinely-ordained re-imagining of the world, nature itself through its own inevitable development leads to that re-imagining, a unity more profound than the unity that existed before the Fall into time. What I want to suggest is that even though Wordsworth does not use the supernatural in presenting this myth, the myth itself and the terms in which it is told — the images and motifs of his writing — are similar to what one finds in much fantasy. Nature, transformations, healing. Wordsworth’s work, specifically The Prelude, therefore has an intimate but unusual relationship to fantasy; from one point of view, it’s what fantasy would be if it weren’t fantastic.

Fall, redemption, apocalypse; and all things are made new. As Abrams points out, Romantic philosophy and poetry have isolated a mythic structure, and are retelling it in new terms, without reference to Christian mythic ideas. Rather than Christ or God stepping in to turn the Fall around and lead ultimately to a divinely-ordained re-imagining of the world, nature itself through its own inevitable development leads to that re-imagining, a unity more profound than the unity that existed before the Fall into time. What I want to suggest is that even though Wordsworth does not use the supernatural in presenting this myth, the myth itself and the terms in which it is told — the images and motifs of his writing — are similar to what one finds in much fantasy. Nature, transformations, healing. Wordsworth’s work, specifically The Prelude, therefore has an intimate but unusual relationship to fantasy; from one point of view, it’s what fantasy would be if it weren’t fantastic.

Abrams observes that the plot structure of the Neoplatonist myth is enacted in Romantic literature in both mimetic and ‘mythic’ forms, as realist biography, and as märchen, or constructed folk-tale — again, a fantasy. I think that Wordsworth, in a number of ways, brings together both approaches. While aiming at realism, and in the case of The Prelude aiming at autobiography, his displacement of the Christian myth anticipates, in its structure and symbols, the form of fantasy.

Having said all of that, I now want to look at The Prelude itself. Because, in addition to the above, I think there’s another level of complexity to Wordsworth’s approach to the fantastic in that poem. And that is Wordsworth’s own conscious use of fiction, and especially fantasy stories, as a symbol; as one element in the highly symbolic story of his own development as a poet.

The Prelude is a kind of dreamlike autobiography. It gives a version of Wordsworth’s life, but one with details changed, and events out of order. In doing this, it creates a structure of its own, leading, as you might imagine, to a moment of revelatory apocalypse. The point is not to retell facts faithfully, nor is it to create narrative tension or traditional characters. It is a recounting by Wordsworth of his own memories, accounting for his development as a poet. What is important is not matters of fact, but what made an impression on his mind and creative powers. Nature and his experience of nature. Human society. And books; his reaction to story and literature. I feel the poem braids these various themes together, leading to its final apocalypse, the eucatastrophe out of which Wordsworth was created as a poet. In talking about the poem, for the sake of clarity I’m going to refrain from using phrases like ‘the poet’ to refer to the main character, and simply call him ‘Wordsworth.’ It still should not be forgotten that there is a distinction between Wordsworth the writer, and Wordsworth who is the subject of the poem.

The Prelude is a kind of dreamlike autobiography. It gives a version of Wordsworth’s life, but one with details changed, and events out of order. In doing this, it creates a structure of its own, leading, as you might imagine, to a moment of revelatory apocalypse. The point is not to retell facts faithfully, nor is it to create narrative tension or traditional characters. It is a recounting by Wordsworth of his own memories, accounting for his development as a poet. What is important is not matters of fact, but what made an impression on his mind and creative powers. Nature and his experience of nature. Human society. And books; his reaction to story and literature. I feel the poem braids these various themes together, leading to its final apocalypse, the eucatastrophe out of which Wordsworth was created as a poet. In talking about the poem, for the sake of clarity I’m going to refrain from using phrases like ‘the poet’ to refer to the main character, and simply call him ‘Wordsworth.’ It still should not be forgotten that there is a distinction between Wordsworth the writer, and Wordsworth who is the subject of the poem.

The Prelude’s written in the form of an extended recollection, a kind of verse letter to Coleridge. In its final form, published in 1850, the poem’s divided into fourteen books. The first introduces us to Wordsworth’s theme, then describes his childhood and early school-years. The second and third books also describe his schooling, and the fourth describes a vacation. The fifth reflects on his experience of reading books, and describes a notably strange dream. The sixth book describes his walking-tour of 1790, and specifically the mix of sublimity and anti-climax he found in crossing the Alps. The seventh book recalls time he spent in London. The eighth book looks back over the poem up to this point, preparing us for the next three books, which describe his time in France and his experience of the Revolution. He is at first intoxicated by Revolutionary ideals — “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” as he famously wrote, “but to be young was very heaven” — but later disappointed by the bloody and undemocratic turn events took. This precipitates a spiritual crisis, and books twelve and thirteen describe the slow resolution of this crisis, returning to memory and nature to renew the visionary sensibility. Finally, in book fourteen, Wordsworth recalls climbing Mount Snowdon, in Wales, and at the mountain’s peak finds an image of imagination and creativity that resolves for him the tension between nature and imagination, between reason and poetry, and brings us full circle back to the point at which Wordsworth began writing the poem. That vision is his apocalypse, his eucatastrophe.

The poem is a poem of imagination; that is its theme. It frequently expresses this theme, as Abrams observes, through images of journeys. Of quests. Across the Alps, or into London, or up Mount Snowdon. The external quests become images of the internal search for inspiration; interior and externals dissolve into each other. Wordsworth’s life becomes a dream, an epic, a myth or a fantasy — or becomes such, at least, in writing; for one of the other recurrent image-systems of the poem is writing, and fiction, and the contrast between nature and the written evocation of nature.

The poem opens with the image of a breeze that seems to imaginatively liberate Wordsworth; then he breaks off, and reveals that what we have been reading isn’t really The Prelude, but only a draft of a possible beginning to The Prelude:

Thus far, O Friend! did I, not used to make

A present joy the matter of a song,

Pour forth that day my soul in measured strains

That would not be forgotten, and are here

Recorded: to the open fields I told

A prophecy: poetic numbers came

Spontaneously to clothe in priestly robe

A renovated spirit singled out,

Such hope was mine, for holy services.

My own voice cheered me, and, far more, the mind’s

Internal echo of the imperfect sound;

To both I listened, drawing from them both

A cheerful confidence in things to come.

The ‘Friend’ is Coleridge, to whom he is ostensibly writing the poem. But the ‘false’ start emphasises the poem as a text; as a thing being written. It is “the mind’s / Internal echo of the imperfect sound” — so not only is the poet’s voice imperfect, but the recollection of the spontaneous poetry is only an echo of the original inspired prophecy.

The poet walks to a tree, where he rests for a time and ponders his next move; he decides then to walk to his home, which he calls before him in memory: “and while upon the fancied scene / I gazed with growing love, a higher power / Than Fancy gave assurance of some work / Of glory there forthwith to be begun”. Coleridge (in his 1817 book of criticism, Biographia Literaria) identifies Fancy as a lesser kind of imagination, linked to memory and not as truly creative. It looks as if Wordsworth is following that distinction here; the memory of his home is a “fancied scene.” If so, then it is presumably the imagination that is the higher power than Fancy, promising the work that will be done. And the work that will follow will illustrate how the imagination works, how it is to be cultivated and how it gives rise to poetry.

The poet walks home, but doesn’t immediately start his work, preoccupied by the necessities of daily life. But he is not sure of his theme; will it be an “old / Romantic Tale by Milton left unsung” (perhaps the story of Arthur, which Milton rejected as a theme for his epic because he felt it to be too limited) or will it be a Spenserian fantasy of chivalry —

grave reports

Of dire enchantments faced and overcome

By the strong mind, and tales of warlike feats,

Where spear encountered spear, and sword with sword

Fought, as if conscious of the blazonry

That the shield bore, so glorious was the strife;

Whence inspiration for a song that winds

Through ever-changing scenes of votive quest

Wrongs to redress, harmonious tribute paid

To patient courage and unblemished truth,

To firm devotion, zeal unquenchable,

And Christian meekness hallowing faithful loves.

Wordsworth is evoking two great English epic writers, effectively promising to do something new, unlike and perhaps greater than either. But there are other options, he goes on to say. He could write about history, presenting an epic of some hero of old time fighting tyranny. Sometimes, he says, he prefers to write a story of his own, “but the unsubstantial Structure melts / Before the very sun that brightens it, / Mist into air dissolving!” He thinks then of a “more philosophic Song / Of Truth that cherishes our daily life” — but feels he is not yet ready, not old enough. Still, he concludes, better to ponder these things than wander aimlessly without “zeal or just ambition.” Nevertheless, he is too conscious of his own inadequacy, leaving him “Unprofitably travelling toward the grave” with no epic accomplishment.

And now, finally, with this crisis of indecision, the poem really begins, as he bursts out with a question to himself:

Was it for this

That one, the fairest of all rivers, loved

To blend his murmurs with my nurse’s song,

And, from his alder shades and rocky falls,

And from his fords and shallows, sent a voice

That flowed along my dreams?

The river is the Derwent, which he lived near as a child and which, as Wordsworth goes on to explain, served to introduce him to the world of nature. Wordsworth describes his infancy and young childhood, and now his story’s off and running: he’s found his theme, unburdened by fears of his poetical predecessors. He has chosen not to match the immediate extravagance of their imaginations, of their narratives and fantasies; he’s writing the story of his mind, how his own imagination was developed to the point where he could see himself joining their company.

But life, as he tells it, is not without a sense of myth to match Milton or Spenser. Consider a story he tells to illustrate how nature will use “Severer interventions” when necessary to foster “The calm existence that is mine when I / Am worthy of myself!” One evening when he was a boy, he found a boat tied to a tree by a rocky cave. He takes the boat; “it was an act of stealth,” he recalls, akin to theft. The boat handles well — “She was an elfin Pinnace” — and he is rowing vigorously when an optical illusion causes a mountain to appear to rise up into his view:

a huge peak, black and huge,

As if with voluntary power instinct,

Upreared its head. I struck and struck again,

And growing still in stature the grim shape

Towered up between me and the stars, and still,

For so it seemed, with purpose of its own

And measured motion like a living thing,

Strode after me. With trembling oars I turned,

And through the silent water stole my way

Back to the covert of the willow tree;

There in her mooring-place I left my bark,—

And through the meadows homeward went, in grave

And serious mood; but after I had seen

That spectacle, for many days, my brain

Worked with a dim and undetermined sense

Of unknown modes of being; o’er my thoughts

There hung a darkness, call it solitude

Or blank desertion. No familiar shapes

Remained, no pleasant images of trees,

Of sea or sky, no colours of green fields;

But huge and mighty forms, that do not live

Like living men, moved slowly through the mind

By day, and were a trouble to my dreams.

I love this passage; and I have to admit, it’s impossible for me to read it without thinking, however irrelevantly, of H.P. Lovecraft. It’s a false association; the “huge and mighty forms” are still, I think, part of the natural world in a way that Lovecraftian powers aren’t. A better connection might be to Blake’s giant forms, his Urizen and Tharmas. In any event, it reads as an incursion of myth into the developing life of the poet. The poem insists here, as it does elsewhere, on the perception of things beyond the merely real. Wordsworth’s visions, his sense of “unknown modes of being,” have imaginative reality of their own.

Much of the rest of the first book describes the poet’s experience of childhood, and playing childhood games. What might have been mundane becomes mythologised:

Ye Presences of Nature in the sky

And on the earth! Ye Visions of the hills!

And Souls of lonely places! can I think

A vulgar hope was yours when ye employed

Such ministry, when ye, through many a year

Haunting me thus among my boyish sports,

On caves and trees, upon the woods and hills,

Impressed, upon all forms, the characters

Of danger or desire; and thus did make

The surface of the universal earth,

With triumph and delight, with hope and fear,

Work like a sea?

Wordsworth is close to animism here, but I also find his mention of “characters,” letters (though also implicitly personalities), impressed upon natural surroundings to be most striking. It’s a mixture of myth, of writing, and of nature. To an extent, the rest of the poem is a falling away from this unity, and its slow recovery.

He goes on, writing of card games like mock-epics with a cast of kings and knaves, or times when “With crosses and with cyphers scribbled o’er, / We schemed and puzzled”. He recalls “Gleams like the flashing of a shield” when the earth spoke to him “sometimes, ‘tis true, / By chance collisions and quaint accidents / (Like those ill-sorted unions, work supposed / Of evil-minded fairies)”. By remembering all these things, he tells Coleridge, he has found a source of strength, and so he decides he will continue on this theme. Thus the first book ends.

The second book recalls schooldays, still happy though more constrained. His knowledge grows, but now he is skeptical of science and reason, “that false secondary power / By which we multiply distinctions”. The reasoning mind alters the world by classifying it, he argues, even as it pretends to only enumerate what’s there. Still, he continued to “drink the visionary power” of Nature:

I would stand,

If the night blackened with a coming storm,

Beneath some rock, listening to notes that are

The ghostly language of the ancient earth,

Or make their dim abode in distant winds.

Language in nature is music; conversely, he ends the book asserting that

I speak, unapprehensive of contempt,

The insinuated scoff of coward tongues,

And all that silent language which so oft

In conversation between man and man

Blots from the human countenance all trace

Of beauty and of love.

Human language and natural language are, then, not the same. One is connective and imaginative. The other is a negation.

Wordsworth moves on to Cambridge in Book Three, where, as though in the wave of “some Fairy’s wand,” he is outfitted as a young gentleman. But he is out of place in the competition for academic achievement, and has “a strangeness in the mind, / A feeling that I was not for that hour, / Nor for that place.” His mind was developing in unusual ways. “Let me dare to speak / A higher language,” he says, describing his still-active perception of the world around him. “To every natural form, rock, fruit or flower … I gave a moral life” he says; “all / That I beheld respired with inward meaning.” This was inherently creative: “I had a world about me — ‘twas my own; / I made it, for it only lived to me, / And to the God who sees into the heart.” To me, Wordsworth is here describing not only a creative act, but a cosmological one. As I read this passage, it seems as though for Wordsworth the making of the world around him out of his sense-perceptions was a kind of ‘sub-creation’ exactly parallel to, if not the same as, the creative act Tolkien describes whereby a writer imagines a world. This implication will recur several times in the poem.

Wordsworth moves on to Cambridge in Book Three, where, as though in the wave of “some Fairy’s wand,” he is outfitted as a young gentleman. But he is out of place in the competition for academic achievement, and has “a strangeness in the mind, / A feeling that I was not for that hour, / Nor for that place.” His mind was developing in unusual ways. “Let me dare to speak / A higher language,” he says, describing his still-active perception of the world around him. “To every natural form, rock, fruit or flower … I gave a moral life” he says; “all / That I beheld respired with inward meaning.” This was inherently creative: “I had a world about me — ‘twas my own; / I made it, for it only lived to me, / And to the God who sees into the heart.” To me, Wordsworth is here describing not only a creative act, but a cosmological one. As I read this passage, it seems as though for Wordsworth the making of the world around him out of his sense-perceptions was a kind of ‘sub-creation’ exactly parallel to, if not the same as, the creative act Tolkien describes whereby a writer imagines a world. This implication will recur several times in the poem.

At the moment, though, “Some called it madness —” he says, and it was, “If prophecy be madness; if things viewed / By poets in old time, and higher up / By the first men, earth’s first inhabitants, / May in these untutored days no more be seen / With undisordered sight.” It’s a defence in mythical language of the urge to art, of the uniqueness of vision. Insofar as it is also a defence of world-building, of the making of an individual sub-creation, it’s also a justification of the fantastic.

But society, and “the bodily eye” which showed him mere physical things, led him away from this creative perspective: “spells seemed on me when I was alone, / Yet could I only cleave to solitude / In lonely places; if a throng was near / That way I leaned by nature; for my heart / Was social, and loved idleness and joy.” So months go on, and he recalls his past, including men now “into phantoms passed / Of texture midway between life and books.” University is a model of the world, “A tournament of blows, some hardly dealt / Though short of mortal combat” — an image out of a chivalric romance, some story of knights and wizards. I think Wordsworth means the associations of the unreal that come with the image, just as the old men he now remembers are unreal ghosts, not only book-like but also like puppets “For entertainment of the gaping crowd / At wake or fair.” We’ll revisit the image of the fair, but for the moment I want to highlight the fact that Wordsworth uses books and language as an image of the meretricious, the disposable, as well as of what is important (as he describes Chaucer, Spenser, and Milton). Slighting books “were to lack / All sense”, but sense is what leads him away from his personal vision. Still, “strong book-mindedness” is a positive value that brings “A healthy sound simplicity”.

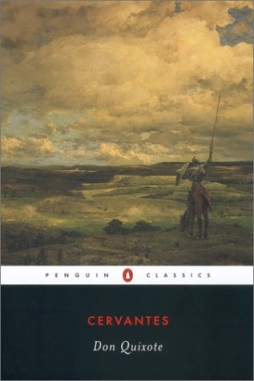

I am going to skip quickly over the fourth book, describing a summer’s vacation, to get to the fifth, where Wordsworth effectively abandons the sense of a chronological story to reflect on books. Meditating on the perishability of books and texts, he describes a strange dream that came upon him once after reading Don Quixote. In this dream, Wordsworth finds himself on a wide featureless plain; an Arab on a dromedary rides up to him bearing a lance, under one arm a stone, and in the other hand a shell filled with light. Wordsworth takes the Arab for a guide. The Arab explains that the stone is Euclid’s Elements, a mathematics textbook, but the shell is more valuable. He holds it out to Wordsworth, and commands the poet to put it to his ear; he does, and hears a prophetic Ode predicting a deluge. The Arab explains that he’s going to bury the books (because stone and shell are also, in the dream, books) to save them from the coming flood. Wordsworth wants to go with him, but the Arab hurries away, and when Wordsworth follows, he realises that the Arab has also become Don Quixote. Behind them the flood comes, and the Arab Quixote hurries away from Wordsworth, who wakes.

I am going to skip quickly over the fourth book, describing a summer’s vacation, to get to the fifth, where Wordsworth effectively abandons the sense of a chronological story to reflect on books. Meditating on the perishability of books and texts, he describes a strange dream that came upon him once after reading Don Quixote. In this dream, Wordsworth finds himself on a wide featureless plain; an Arab on a dromedary rides up to him bearing a lance, under one arm a stone, and in the other hand a shell filled with light. Wordsworth takes the Arab for a guide. The Arab explains that the stone is Euclid’s Elements, a mathematics textbook, but the shell is more valuable. He holds it out to Wordsworth, and commands the poet to put it to his ear; he does, and hears a prophetic Ode predicting a deluge. The Arab explains that he’s going to bury the books (because stone and shell are also, in the dream, books) to save them from the coming flood. Wordsworth wants to go with him, but the Arab hurries away, and when Wordsworth follows, he realises that the Arab has also become Don Quixote. Behind them the flood comes, and the Arab Quixote hurries away from Wordsworth, who wakes.

In an early draft of The Prelude, Wordsworth had presented the dream as something that happened to a friend; in the final draft, he wrote it as though it had been his own, making the experience more direct. In fact, some of it seems to have been based on a dream described by Descartes. So there has been much speculation about whether the dream actually was Wordsworth’s own or not; but either way it has the feel of a real dream, in its illogic and in the way that what should be a single thing is actually two things at once.

What does it mean? The passage has been said to be about Wordsworth’s fear of his own poetic achievement being wiped out, but there seems to be a greater resonance to it than that. Some of that comes from ambiguity; Wordsworth never specifies, for example, what the shell represents, exactly. It’s often assumed to be a symbol of imaginative poetry, but then it’s also perhaps the prophetic spirit — it predicts the deluge. It’s filled with light, the key to vision, and is said to be more valuable than a book symbolising science.

What about the Arab? Later in Book V, Wordsworth will reminisce about the importance of the Arabian Nights to him when he was a child; and Don Quixote, as well as being a story that begins with the destruction of books, is the story of a man who dreams that he is a knight out of romance (a ‘romance’ here is an adventurous story of knight-errants, mostly from the Middle Ages; in Wordsworth’s time, they were regarded as simplistic and trite). So the Arab Quixote seems to be a figure of fantasy, then, one on an impossible quest. I wonder if he’s not even a broader symbol than that — there was a theory around Wordsworth’s time that romances, wonder-stories, had come into Europe from Arabic sources.

What about the Arab? Later in Book V, Wordsworth will reminisce about the importance of the Arabian Nights to him when he was a child; and Don Quixote, as well as being a story that begins with the destruction of books, is the story of a man who dreams that he is a knight out of romance (a ‘romance’ here is an adventurous story of knight-errants, mostly from the Middle Ages; in Wordsworth’s time, they were regarded as simplistic and trite). So the Arab Quixote seems to be a figure of fantasy, then, one on an impossible quest. I wonder if he’s not even a broader symbol than that — there was a theory around Wordsworth’s time that romances, wonder-stories, had come into Europe from Arabic sources.

The Arab then is a symbol of romance, of wonder, bearing with him science on the one hand and visionary poetry on the other. His quest is ambiguous, worthy but impossible, literally Quixotic; and yet the nature of the dream undercuts that Quixotic madness. Quixote saw windmills as giants, the Arab has a stone and shell that are books — but they are books, as much as they are stone and shell, and more than single books, as well. Perhaps the windmill really is a giant, as well as a windmill. Quixote was mad and yet perhaps also in his way a visionary (which is why his story has lasted), and so the Arab is misguided but in some way valuable: “A gentle dweller in the desert, crazed / By love and feeling, and internal thought / Protracted among endless solitudes;” but “Nor have I pitied him; but rather felt / Reverence was due to a being thus employed; / And thought that, in the blind and awful lair / Of such a madness, reason did lie couched.”

I think it’s significant that the Arab Quixote seems to become a symbol of liberation — for Wordsworth, in the dream, sees him as the way out of the waste land around him. I think that perspective on books and literature, on fiction and on fantasy, informs much of the rest of Wordsworth’s discussion of books in Book V. Consider how he then goes on to compare the power of nature and fiction, “other guides / And dearest helpers” — he says that in his time of “prattling childhood,” his first careless years of language use, in a natural scene “It might have well beseemed me to repeat / Some simply fashioned tale, to tell again, / In slender accents of sweet verse, some tale / That did bewitch me then, and soothes me now.” So the tale bewitches, ensorcells, catches by magic like the work of a wizard in a romance; it soothes; and it is important, for it ought to be associated with the joy of nature.

Wordsworth then breaks into an assertion of the importance of poets, all poets from Homer down to the humblest ballad-maker, “in the memory of all books which lay / Their sure foundation in the heart of man.” As he says:

from those loftiest notes

Down to the low and wren-like warblings, made

For cottagers and spinners at the wheel,

And sun-burnt travellers resting their tired limbs,

Stretched under wayside hedge-rows, ballad tunes,

Food for the hungry ears of little ones,

And of old men who have survived their joys

What I want to emphasise here is Wordsworth’s depiction of poetry as consolation, as something as important as food for old and young alike. Ballads were popular verse, and typically intensely narrative, often fantastic or legendary. Wordsworth is affirming not carefully refined literary art, I think, so much as he is the importance of storytelling; the ability of story to provide something psychologically important.

Storytellers and their stories, he says, are “only less, / For what we are and what we may become, / Than Nature’s self, which is the breath of God, / Or His pure Word by miracle revealed.” In fact, he says in this passage that he is pronouncing their “benediction,” that they are “for ever to be hallowed”; I can’t help but notice the religious language, and think that he intends to associate storytellers with God, and perhaps by implication Nature.

As a contrast to the above, he tries to imagine what he and Coleridge would have been like if they had not been exposed to stories as children:

Where had we been, we two, beloved Friend!

If in the season of unperilous choice,

In lieu of wandering, as we did, through vales

Rich with indigenous produce, open ground

Of Fancy, happy pastures ranged at will,

We had been followed, hourly watched, and noosed,

Each in his several melancholy walk

Stringed like a poor man’s heifer at its feed,

Led through the lanes in forlorn servitude;

Or rather like a stalled ox debarred

From touch of growing grass, that may not taste

A flower till it have yielded up its sweets

A prelibation to the mower’s scythe.

Wordsworth is presenting here perfect images of storytelling as escapism in the best sense: storytelling as liberation. Again, I think this echoes his image of the Arab Quixote; the hope of freedom a story provides, the intimation of an escape from coming doom. As a contrast to all this, Wordsworth tries to imagine a child instructed in perfect rationality, and concludes that such a creature would be cut off from nature:

Meanwhile old grandame earth is grieved to find

The playthings, which her love designed for him,

Unthought of: in their woodland beds the flowers

Weep, and the river sides are all forlorn.

Oh! give us once again the wishing cap

Of Fortunatus, and the invisible coat

Of Jack the Giant-killer, Robin Hood,

And Sabra in the forest with Saint George!

The child whose love is here, at least, doth reap

One precious gain, that he forgets himself.

So nature and stories, fairy stories, are alike important to youth; and are somehow related. It seems that through the use of fiction, of legends, one comes to nature. For Wordsworth, fairy stories prepare one for later life; as he says, when he sees a corpse, he is not afraid,

for my inner eye had seen

Such sights before, among the shining streams

Of faery land, the forest of romance.

Their spirit hallowed the sad spectacle

With decoration of ideal grace;

A dignity, a smoothness, like the words

Of Grecian art, and purest poesy.

There’s obviously irony there, but I think the point is truly felt as well.

After describing his desire, when he was young, for a four-volume set of the Arabian Nights, Wordsworth stresses the importance of romances:

A gracious spirit o’er this earth presides,

And o’er the heart of man; invisibly

It comes, to works of unreproved delight,

And tendency benign, directing those

Who care not, know not, think not, what they do.

The tales that charm away the wakeful night

In Araby, romances; legends penned

For solace by dim light of monkish lamps;

Fictions, for ladies of their love, devised

By youthful squires; adventures endless, spun

By the dismantled warrior in old age,

Out of the bowels of those very schemes

In which his youth did first extravagate;

These spread like day, and something in the shape

Of these will live till man shall be no more.

Dumb yearnings, hidden appetites, are ours,

And they must have their food. Our childhood sits,

Our simple childhood, sits upon a throne

That hath more power than all the elements.

I think that last point about childhood is vital. Romances in this book are consistently associated with childhood. Wordsworth’s returning here to something like the myth of the ‘Intimations’ Ode; the child who brings glory from a spirit-realm that precedes existence in this world, a glory which fades as one ages. Here, though, the child has a power above Nature, “more power than all the elements.” It’s a power that fades, but is not wholly lost in “the long probation that ensues, / The time of trial, ere we learn to live / In reconcilement with our stinted powers;” which probation Wordsworth still sees as a necessity. But during one’s visionary youth, romance is a vital consolation as one comes to deal with a bleaker, less visionary world:

Ye dreamers, then,

Forgers of daring tales! we bless you then,

Impostors, drivellers, dotards, as the ape

Philosophy will call you: then we feel

With what, and how great might ye are in league,

Who make our wish, our power, our thought a deed,

An empire, a possession,—ye whom time

And seasons serve; all Faculties to whom

Earth crouches, the elements are potter’s clay,

Space like a heaven filled up with northern lights,

Here, nowhere, there, and everywhere at once.

The romancer, the fantasist, can reshape reality. If we are destined to live in a bleak world, perhaps even the waste land from which the Arab Quixote promised escape, romance is a hint of a way out. The romancer is in league with ‘great might’ — nature and imagination. Rational philosophy, itself merely imitative (an ape), can view fantasy only as an imposture or as madness. It does not partake of the visionary nature of youth. For if these romances are associated with childhood, childhood itself is associated by Wordsworth with visionary power. The romance therefore partakes of the quality of the vision. If viewed rationally, it is drivel. If viewed with the eye of a visionary or of a child, it has wonder to it, and the ability to remake the world.

Wordsworth then passes to “ground, though humbler, not the less a tract / Of the same isthmus,” in which

craving for the marvellous gives way

To strengthening love for things that we have seen;

When sober truth and steady sympathies,

Offered to notice by less daring pens,

Take firmer hold of us, and words themselves

Move us with conscious pleasure.

I note here that he emphasises, not the difference between fantasy and mimetic fiction, but the similarity. They’re effectively the same thing. And, ultimately, what matters at this point is not so much the story but “words themselves”. He recalls the time, at about ten years of age, when he began to respond to poetic phrasing, and he and a friend would wander about chanting favourite lines “Lifted above the ground by airy fancies, / More bright than madness or the dreams of wine;” they were driven, he says, by “no vulgar power” but “That wish for something loftier, more adorned, / Than is the common aspect, daily garb, / Of human life” — the love of romance, then, transformed into the love of poetry and language. Language, at its best, has that power of romance, of fantasy.

So, Wordsworth says, one who knows nature, has experienced it as a youth, gains a greater appreciation of poetry, by being better able to understand nature as it’s depicted in words. Nature and language come together at the conclusion of Book V, and:

Visionary power

Attends the motions of the viewless winds,

Embodied in the mystery of words:

There, darkness makes abode, and all the host

Of shadowy things work endless changes,—there,

As in a mansion like their proper home,

Even forms and substances are circumfused

By that transparent veil with light divine,

And, through the turnings intricate of verse,

Present themselves as objects recognised,

In flashes, and with glory not their own.

Winds in The Prelude are a constant symbol of the creative imagination, of inspiration; here we see why, as they are both an element of nature and the carriers of sound. The winds are the airs from the lungs of the chanting poets. The winds are embodied in words, which are both shadows of the actual world of Nature, and also veils bearing visionary glory.

Unlike much of the rest of The Prelude, Book V doesn’t even pretend to give a chronological recounting of experience. But I think it’s important that it be situated right where it is, as it sets up a fair amount of what follows. In its depiction of the intermingling of language, fiction, and nature, I think it prepares the way for what happens in the following books; and specifically in the way it describes the imagination playing with nature, being blessed or sanctified by taking part in an almost divine process of creation.

So in Book VI, Wordsworth returns to his more-nearly-chronological structure, describing his return to Cambridge and later walking-trip through the Alps. He aspires to authorship, and recalls a certain tree:

Often have I stood

Foot-bound uplooking at this lovely tree

Beneath a frosty moon. The hemisphere

Of magic fiction, verse of mine perchance

May never tread; but scarcely Spenser’s self

Could have more tranquil visions in his youth,

Or could more bright appearances create

Of human forms with superhuman powers,

Than I beheld, loitering on calm clear nights

Alone, beneath this fairy work of earth.

Nature and imagination are joined in him. If Wordsworth acknowledges turning away from “magic fiction,” still he claims the experience of envisioning heroic fictions to match his great predecessor Spenser.

Wordsworth then describes his joy in abstract science, and does so in what at first appears an odd way. He recalls a story of a mariner who was shipwrecked with several other people, and saved a geometry textbook (another voyager, and inevitably recalling the Arab Quixote by his rescue from a deluge with a geometry book); that mariner often went off on his own and drew geometrical designs in the sand to distract himself from his present situation. On the one hand, the “stormy” shipwreck and “long staff” used to mark out abstruse, mysterious designs may recall The Tempest; but on the other, the mariner there is using science much as Wordsworth has described the use of romance: a distraction from a painful world. “So was it then with me, and so will be/ With Poets ever”, says Wordsworth, imagining a link between poetry and science that hasn’t really continued. But for him, “Mighty is the charm / Of those abstractions to a mind beset / With images and haunted by herself,” specifically because what they create is “an independent world, / Created out of pure intelligence.” So science, like romance, plays with nature so as to create a world.

Elsewhere in Book VI, Wordsworth returns to the joy of concrete experience of Nature, a joy that now seems mediated by the experience of books and stories. For example, he describes a castle once supposedly visited by Sir Philip Sidney, an Elizabethan soldier-courtier-poet-spy who wrote a famous romance called Arcadia; and then describes visiting this castle with his sister, how

having clomb

The darksome windings of a broken stair,

And crept along a ridge of fractured wall,

Not without trembling, we in safety looked

Forth, through some Gothic window’s open space,

And gathered with one mind a rich reward

From the far-stretching landscape, by the light

Of morning beautified, or purple eve[.]

The use of the word “Gothic” seems pointed; the anecdote describes a ruined castle, a woman (Dorothy Wordsworth) within it, an atmosphere of fear, and the sublimity of landscape — all elements of the literary Gothic. The mention of Sidney seems especially relevant, at once an insistence on the castle’s antiquity and also an evocation of the romance. The emotional tenor of the passage is clear: a dangerous, frightful journey, which eventually pays off in the “rich reward” of landscape beautified by dawn light. A hard road and the visionary experience of nature.

I mention it here because it seems to me to contrast intriguingly with later passages of the book. Wordsworth describes (in passages which set up his later experiences in France in Books IX and X) his passage through a France bursting with revolutionary promise and springlike optimism: “Enchanting show / Those woods and farms and orchards did present,” he declares. That enchantment will later be dismissed, but for the moment, it’s his perception of the world around him; he is moving through a land that is like something of a utopian romance — out of Sidney’s Arcadia, perhaps. Only a major anticlimax is in store on this trip, which perhaps could be a warning for what will come.

I mention it here because it seems to me to contrast intriguingly with later passages of the book. Wordsworth describes (in passages which set up his later experiences in France in Books IX and X) his passage through a France bursting with revolutionary promise and springlike optimism: “Enchanting show / Those woods and farms and orchards did present,” he declares. That enchantment will later be dismissed, but for the moment, it’s his perception of the world around him; he is moving through a land that is like something of a utopian romance — out of Sidney’s Arcadia, perhaps. Only a major anticlimax is in store on this trip, which perhaps could be a warning for what will come.

First, reaching the Alps, he sees from the distance the highest of the Alpine peaks, Mont Blanc, “and grieved / To have a soulless image on the eye / That had usurped upon a living thought / That never more could be.” Mont Blanc would develop into a major Romantic symbol, but the point here is that the actual experience of the mountain ‘usurps’ the imaginary sense of the mountain Wordsworth had previously had. Reality dethrones fantasy. Still, as he says, he and the friend with whom he was travelling could not “fail to abound / In dreams and fictions, pensively composed:” the natural scenery around them was too powerful. It forced them into visionary experience, into creativity.

But, as Wordsworth describes, they later crossed the Alps without realising when the pass they had taken had reached its highest point. Unknowing, he had passed the apex of experience. Thinking back on that point, he feels stronger now, has recovered his imaginative poise, knows that “Our destiny, our being’s heart and home, / Is with infinitude, and only there; / With hope it is, hope that can never die, / Effort, and expectation, and desire, / And something evermore about to be.” At the time, though, the descent through sublime natural scenery was dizzying. The sights around him

Were all like workings of one mind, the features

Of the same face, blossoms upon one tree;

Characters of the great Apocalypse,

The types and symbols of Eternity,

Of first, and last, and midst, and without end.

Nature has become literally overwritten — “Characters of the great Apocalypse”. That shock creates the later harmony Wordsworth has already described; nature will give the poet the ability to overcome its own disappointment. The ability to see the apocalypse in the natural world around him comes from the imaginative upheaval of crossing the Alps unawares. The world creates the ability to later remake the world. As the poem presents things, though, it seems that at the time of that journey across the Alps, Wordsworth only overcomes this shock through the beautiful scenes he sees elsewhere in the mountains, notably around Locarno and Como. At any rate, with the recovery of that stability, the book ends.

Book VII recalls Wordsworth’s time spent living in London. It’s highly ambiguous. The city’s cut off from nature, and home to terrifying scenes of poverty. But it’s also a place of marvels. Like Mont Blanc, it meant a considerable about to Wordsworth imaginatively before he ever saw it:

There was a time when whatsoe’er is feigned

Of airy palaces, and gardens built

By Genii of romance; or hath in grave

Authentic history been set forth of Rome,

Alcairo, Babylon, or Persepolis;

Or given upon report by pilgrim friars,

Of golden cities ten months’ journey deep

Among Tartarian wilds—fell short, far short,

Of what my fond simplicity believed

And thought of London—held me by a chain

Less strong of wonder and obscure delight.

So London is associated with wonder, and with romance. As we’ll see, the experience of London didn’t displace these fantasies as the reality of Mont Blanc displaced the imagined mountain. When he goes to the “monstrous ant-hill,” he sees shops identified by “symbols, blazoned names,” and the fronts of pubs “like a title-page, / With letters huge inscribed from top to toe” and covered with “allegoric shapes”.

A raree-show is here,

With children gathered round; another street

Presents a company of dancing dogs,

Or dromedary, with an antic pair

Of monkeys on his back; a minstrel band

Of Savoyards; or, single and alone,

An English ballad-singer.

Again the eye for the marvellous; the notice also of ballad-singers and minstrels, poets and storytellers. Among the “labyrinths” of the city, “files of ballads dangle from dead walls;” this is a place of language. It is in fact multilingual and multicultural, as he sees “every character of form and face”, among them Swedes and Russians and American Indians and Malays and Chinese “And Negro Ladies in white muslin gowns.”

Mainly, though, there are “spectacles” in art galleries and especially theatres. He watches on stage “giants and dwarfs, / Clowns, conjurors, posture-masters, harlequins, / Amid the uproar of the rabblement, / Perform their feats.” Recalling Book V’s list of childhood heroes, he sees an invisible Jack the Giant-killer — “The garb he wears is black as death, the word / ‘Invisible’ flames forth upon his chest.” And as in Book V, he goes on to describe more realistic stories: “dramas of living men, / And recent things yet warm with life; a sea-fight, / Shipwreck, or some domestic incident / Divulged by Truth and magnified by Fame”.

The paradox Wordsworth goes on to describe is that the stage was “Outweighed, or put to flight,” by reality; but it had a fascination for him nevertheless, occasionally overwhelming reality. “Yet was the theatre my dear delight; / The very gilding, lamps and painted scrolls, / And all the mean upholstery of the place, / Wanted not animation” he claims, and describes scenes like things out of romance: women wandering in forests, kings in their pomp, manacled prisoners, and so forth. The audience is itself part of the show; “Enchanting age and sweet! / Romantic almost, looked at through a space, / How small, of intervening years!” The whole experience recalls visionary childhood: “something of a girlish child-like gloss / Of novelty survived for scenes like these;” and Wordsworth recalls when he was younger watching a play in a country playhouse when

the bare thought of where I was

Gladdened me more than if I had been led

Into a dazzling cavern of romance,

Crowded with Genii busy among works

Not to be looked at by the common sun.

Paradoxically, the feeling isn’t just caused by the story; it’s caused by being jarred out of the story, by being returned to oneself and aware of the play as a play.

From the theatre, Wordsworth goes to describe his pleasure at watching lawyers and politicians, “tongue-favoured men,” dispute. With fine irony, he describes a politician “like a hero in romance” who “winds away his never-ending horn;” that’s a specific allusion to Roland, Charlemagne’s knight, and so again this is foreshadowing of and contrast to the political strife Wordsworth will find in France (and specifically in Book X the death of Madame Roland) — something made even more pointed by a late insertion of a long passage in which Wordsworth praises Edmond Burke, the orator and Tory politician whose 1790 Reflections on the Revolution in France was a best-selling counter-Revolutionary pamphlet.

From the theatre, Wordsworth goes to describe his pleasure at watching lawyers and politicians, “tongue-favoured men,” dispute. With fine irony, he describes a politician “like a hero in romance” who “winds away his never-ending horn;” that’s a specific allusion to Roland, Charlemagne’s knight, and so again this is foreshadowing of and contrast to the political strife Wordsworth will find in France (and specifically in Book X the death of Madame Roland) — something made even more pointed by a late insertion of a long passage in which Wordsworth praises Edmond Burke, the orator and Tory politician whose 1790 Reflections on the Revolution in France was a best-selling counter-Revolutionary pamphlet.

Wordsworth describes being dizzied by the sheer number of people in the city, the mystery each one of them represented to him “Until the shapes before my eyes became / A second-sight procession, such as glides / Over still mountains, or appears in dreams;” so that once, when he saw a blind beggar, “upon his chest / Wearing a written paper, to explain / His story” the man seemed a symbol “of the utmost we can know, / Both of ourselves and of the universe”. Again, language distinct from a thing.

The whirl of the city, of all its spectacles, of the speeches and the romantic wonders, as well as its terrifying dizzying labyrinths, is summed up by a description of Saint Bartholomew’s Fair. It was a five-day fair that drew all sorts of merchants and entertainers —

All moveables of wonder, from all parts,

Are here—Albinos, painted Indians, Dwarfs,

The Horse of knowledge, and the learned Pig,

The Stone-eater, the man that swallows fire,

Giants, Ventriloquists, the Invisible Girl,

The Bust that speaks and moves its goggling eyes,

The Wax-work, Clock-work, all the marvellous craft

Of modern Merlins, Wild Beasts, Puppet-shows,

All out-o’-the-way, far-fetched, perverted things,

All freaks of nature, all Promethean thoughts

Of man, his dulness, madness, and their feats

All jumbled up together, to compose

A Parliament of Monsters.

Language is no use:

the midway region, and above,

Is thronged with staring pictures and huge scrolls,

Dumb proclamations of the Prodigies;

With chattering monkeys dangling from their poles

So, “dumb” on the one hand and “chattering” on the other, it is “blank confusion! true epitome / Of what the mighty City is herself,” at least to most people. But to some, “to him who looks / In steadiness, who hath among least things / An under-sense of greatest” — to someone who has an experience of nature, the “changeful language” of “ancient hills”, or indeed “what pregnant show / Of beauty, meets the sun-burnt Arab’s eye” — still the city has value. Wordsworth therefore concludes the book by saying that

The soul of Beauty and enduring Life

Vouchsafed her inspiration, and diffused,

Through meagre lines and colours, and the press

Of self-destroying, transitory things,

Composure, and ennobling Harmony.

Book VIII then opens with an immediate contrast between Bartholomew Fair and a rural country fair. This book is intended as a retrospective and summation of the poem so far, and much of it, extending a theme from the previous book, is to do with the contrast between fiction and reality. Between, for example, the shepherds of traditional pastorals and romances, and the actual shepherds Wordsworth knew from his real life.

His essential argument is that the real shepherds are also paradoxically “more of an imaginative form” — more useful, perhaps, for visionary purposes. He remembers, for example, seeing a shepherd “In size a giant, stalking through thick fog, / His sheep like Greenland bears”; through such visionary moments the human form became ennobled for him. To “ye who pore / On the dead letter,” this will be delusion, but Wordsworth insists this is not so.

The problem came when he tried to cast this understanding into verse, which brought “Among the simple shapes of human life / A wilfulness of fancy and conceit”. This led to a desire to fictionalise everything, often to a ludicrous extent:

From touch of this new power

Nothing was safe: the elder-tree that grew

Beside the well-known charnel-house had then

A dismal look: the yew-tree had its ghost,

That took his station there for ornament:

The dignities of plain occurrence then

Were tasteless, and truth’s golden mean, a point

Where no sufficient pleasure could be found.

This was a negative romanticising, a lurching into melodrama unredeemed by vision. It is specially connected with old romances as well, as when a rock shining in the sun became

for me a burnished silver shield

Suspended over a knight’s tomb, who lay

Inglorious, buried in the dusky wood:

An entrance now into some magic cave

Or palace built by fairies of the rock;

Nor could I have been bribed to disenchant

The spectacle, by visiting the spot.

Thus wilful Fancy, in no hurtful mood,

Engrafted far-fetched shapes on feelings bred

By pure Imagination: busy Power

She was, and with her ready pupil turned

Instinctively to human passions, then

Least understood.

So like Mont Blanc, like London, the physical reality of a place could disenchant it. But the enchantment here comes only from Fancy, not Imagination. He’s regurgitating other peoples’ fantasies, not working with his own feelings. Sometimes, as he makes clear, his higher imaginative powers did break through; but he was still, at this time, young. He looks back over his life, his youth at university and time in London; he imagines a traveller passing into a cave or “the Den / In old time haunted by that Danish Witch, / Yordas” (who was said to have lived in a cave in Yorkshire). He imagines weak light playing across the rock of the cave:

Substance and shadow, light and darkness, all

Commingled, making up a canopy

Of shapes and forms and tendencies to shape

That shift and vanish, change and interchange

Like spectres,—ferment silent and sublime!

[…]

Till the whole cave, so late a senseless mass,

Busies the eye with images and forms

Boldly assembled,—here is shadowed forth

From the projections, wrinkles, cavities,

A variegated landscape,—there the shape

Of some gigantic warrior clad in mail,

The ghostly semblance of a hooded monk,

Veiled nun, or pilgrim resting on his staff:

Strange congregation! yet not slow to meet

Eyes that perceive through minds that can inspire.

Figures of romance again, created by mind and eye: “Even in such sort had I at first been moved,” Wordsworth says, as he explored London. So “the place / Was thronged with impregnations like the Wilds / In which my early feelings had been nursed”, and so Wordsworth came to greater understanding of the importance of human beings. The misery he saw in the city failed to “induce belief / That I was ignorant, had been falsely taught, / A solitary, who with vain conceits / Had been inspired, and walked about in dreams.” Thus the book ends. I want to emphasise that image of the cave, though, which recalls the famous Platonic allegory of prisoners in a cave seeing shadows on the wall, the closest they can come to reality. Wordsworth inverts that idea. His cave is made to live, to be filled with clerics and armoured warriors, by the inspired mind. The cave, an image of London, has value through the power of the visionary sight working upon its shadows.

Book IX sees Wordsworth return to France, to the Revolution. He writes of the turmoil, “Hawkers and Haranguers, hubbub wild! / And hissing Factionists with ardent eyes, / In knots, or pairs, or single.” France is “a theatre, whose stage was filled / And busy with an action far advanced.” He has read the “master pamphlets of the day”, pieces for and against the Revolution, but the pamphlets and newspapers aren’t able to really show what’s happening — again, the gap between word and reality.

Wordsworth says that at this time he valued history like poetry, “as it made the heart / Beat high, and filled the fancy with fair forms, / Old heroes and their sufferings and their deeds”; so he presents at first the Revolution as romance. He argues with “defenders of the Crown”, finding their words easily turned back against them. But his Revolutionary friend Beaupuis “through the events / Of that great change wandered in perfect faith, / As through a book, an old romance, or tale / Of Fairy, or some dream of actions wrought / Behind the summer clouds.” Wordsworth describes their idealism in tremendously moving terms; to the point where he felt himself to be walking through an epic by Ariosto or Boiardo:

Sometimes methought I saw a pair of knights

Joust underneath the trees, that as in storm

Rocked high above their heads; anon, the din

Of boisterous merriment, and music’s roar,

In sudden proclamation, burst from haunt

Of Satyrs in some viewless glade, with dance

Rejoicing o’er a female in the midst,

A mortal beauty, their unhappy thrall.

He even regrets the anti-clerical aspect of the Revolution, insofar as it deprives the woods in which he walks of the image of the holy hermits of romance. In fact, Wordsworth finds himself caught between sympathy for the Revolution and his imaginative sympathy with the knights and kings of romance:

Imagination, potent to inflame

At times with virtuous wrath and noble scorn,

Did also often mitigate the force

Of civic prejudice, the bigotry,

So call it, of a youthful patriot’s mind;

And on these spots with many gleams I looked

Of chivalrous delight.

This is another paradox. The Revolution, he hopes, will bring “better days / To all mankind.” But it is opposed to poetry; it is driven by Reason.

In his first draft of the end of Book IX, Wordsworth ended with a kind of versified romance, a tale taken from the writings of Helen Maria Williams about a pair of young lovers named Vaudracour and Julia; in his final draft he removed it, perhaps because it cut too close to his own experiences with Annette Vallon. In any event, Book X begins with terror and confusion. Wordsworth returns to Paris, where he

gazed

On this and other spots, as doth a man

Upon a volume whose contents he knows

Are memorable, but from him locked up,

Being written in a tongue he cannot read,

So that he questions the mute leaves with pain,

And half upbraids their silence.

That night “the fear gone by / Pressed on me almost like a fear to come.” He is caught in a nightmarish vision like something out of Macbeth “Until I seemed to hear a voice that cried, / To the whole city, ‘Sleep no more.’” Robespierre is denounced in print, but it does no good. Things grow worse, Wordsworth returns dispirited to England, England and France go to war. Wordsworth is afflicted by “ghastly visions” of torture; of himself pleading “Before unjust tribunals.” Finally, the book ends with a partial salvation, the death of Robespierre; Wordsworth describes the great event as it was reported to him, while he stood mourning by the grave of a teacher who had first had him write poetry. So the world-historical importance of the fall of Robespierre is associated with the personal experience of Wordsworth — and specifically with the experience of growing into poetry. For the news of the death of Robespierre makes the world seem a happy place, and Wordsworth spontaneously composes “a hymn of triumph.”

Book XI opens with a rumination on the errors of youth and enthusiasm, one summed up, again, by an image out of a romance:

I had approached, like other youths, the shield

Of human nature from the golden side,

And would have fought, even to the death, to attest

The quality of the metal which I saw.

The idea is that the shield has different colours on either side, so that a knight seeing it from one side would swear it was one colour and another knight coming from another side would swear it was something completely different. Once again romance is associated with youth. Wordsworth then describes himself attempting, early on during the Revolution, to work out from books of political science the best way to regulate a country:

O pleasant exercise of hope and joy!

For mighty were the auxiliars which then stood

Upon our side, us who were strong in love!

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very Heaven! O times,

In which the meagre, stale, forbidding ways

Of custom, law, and statute, took at once

The attraction of a country in romance!

When Reason seemed the most to assert her rights

When most intent on making of herself

A prime enchantress—to assist the work,

Which then was going forward in her name!

In context, this encomium of the Revolution is intensely ironic, but it’s another example of the fallibility of books. And of Wordsworth depicting the world around him as something out of a fantasy. Reason becomes an enchantress. And so

the meek and lofty

Did both find, helpers to their hearts’ desire,

And stuff at hand, plastic as they could wish,—

Were called upon to exercise their skill,

Not in Utopia,—subterranean fields,—

Or some secreted island, Heaven knows where!

But in the very world, which is the world

Of all of us,—the place where, in the end,

We find our happiness, or not at all!

This recalls the lines from the “Prospectus:”

Paradise, and groves

Elysian, Fortunate Fields — like those of old

Sought in the Atlantic Main, why should they be

A history only of departed things,

Or a mere fiction of what never was?

As we’ll see, between this point in The Prelude and the writing of the “Prospectus,” Wordsworth has come to realise that Utopia isn’t something one builds in the objective world of society. It’s something one sees, and creates in art; something one builds in one’s own subjective perception of things. You don’t need an external Revolution, only visionary awareness.