Christopher Paul Carey on Philip José Farmer’s World of Khokarsa

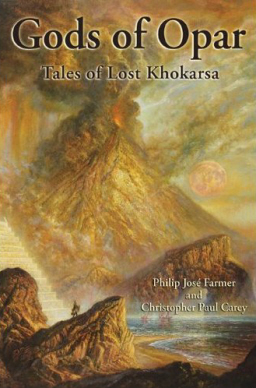

With the publication of Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa, I thought I’d take the opportunity to give Black Gate readers a taste of the world of Khokarsa, which serves as the setting for Philip José Farmer’s epic series of adventure and historical fantasy. It’s a world I’ve been immersed in for the past several years as I worked to complete The Song of Kwasin, the concluding book in the Khokarsa trilogy, as well as other related projects set in Farmer’s prehistoric empire.

With the publication of Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa, I thought I’d take the opportunity to give Black Gate readers a taste of the world of Khokarsa, which serves as the setting for Philip José Farmer’s epic series of adventure and historical fantasy. It’s a world I’ve been immersed in for the past several years as I worked to complete The Song of Kwasin, the concluding book in the Khokarsa trilogy, as well as other related projects set in Farmer’s prehistoric empire.

Farmer’s achievement in the first two Khokarsa novels — written and first published in the 1970s, and now available in the Gods of Opar omnibus — is impressive. And part of the reason these thirty-some-year-old books hold up so well is the lengths to which the author went to carefully construct a believable world for his prehistoric heroes, heroines, and villains.

The rich level of cultural and descriptive detail in both Hadon of Ancient Opar and its sequel Flight to Opar make them prime examples of fantastic world building. Set twelve thousand years ago in ancient Africa against the backdrop of a civil war between the priestesses and the priests in the empire of Khokarsa, the books unveil a complex pantheon of gods and goddesses.

First and foremost is Kho, known also as the Mother Goddess, the White Goddess, and the Mother of All. She is the central deity of the Khokarsan people. Carefully balanced against Kho is her son Resu, god of the sun, rain, and war. While Resu has been declared the equal of his mother, most Khokarsans still regard Resu as secondary to Kho.

At the time Hadon of Ancient Opar begins, the priests of Resu have been locked in a delicate struggle for supremacy with the priestesses of Kho for over eight hundred years.

Many other intriguing deities, both lesser and greater, intimately influence everyday life in Khokarsa. There is Adeneth, goddess of sexual passion; Besbesbes, goddess of bees and mead; Bukhla, the goddess of war before she was usurped by Resu; Kasukwa, the river godling; Khuklaqo, the Shapeless Shaper; Khukly, the heron goddess; Lahla, “Kho’s fairest daughter,” goddess of the moon and patroness of music and poetry; Piqabes, “the green-eyed daughter of Kho,” goddess of the sea; the dread Sisisken, “grim ruler of the shadow world”; and Tesemines, goddess of the night.

Many other intriguing deities, both lesser and greater, intimately influence everyday life in Khokarsa. There is Adeneth, goddess of sexual passion; Besbesbes, goddess of bees and mead; Bukhla, the goddess of war before she was usurped by Resu; Kasukwa, the river godling; Khuklaqo, the Shapeless Shaper; Khukly, the heron goddess; Lahla, “Kho’s fairest daughter,” goddess of the moon and patroness of music and poetry; Piqabes, “the green-eyed daughter of Kho,” goddess of the sea; the dread Sisisken, “grim ruler of the shadow world”; and Tesemines, goddess of the night.

But perhaps none of these Khokarsan deities is as intriguing as Sahhindar, the Gray-Eyed Archer God, and also the god of plants, of bronze, and of Time. Legend has it that he was doomed to wander in exile at the edge of the world after he stole Time from his mother Kho.

A note in Farmer’s “Chronology of Khokarsa” (included in Gods of Opar) indicates that Sahhindar is undoubtedly the time-traveling character John Gribardsun from Farmer’s novel Time’s Last Gift (a new edition of this classic novel, which includes my afterword explaining how the book relates to both the Khokarsa series and Farmer’s Wold Newton Family, is now available from Titan Books).

Many other aspects of Khokarsan society are revealed in the novels. For example, the reader learns that the empire is held together with totemic glue. Hadon is a member of the Fish-Eagle Totem, while other characters belong to such clans as the Ant Totem, the Leopard Totem, or the Pig Totem. These totems are local organizations with widely varied customs.

All Khokarsans, however, observe a nine-year cycle, represented by “a fish-eagle, a hippopotamus, a green parrot, the hero Gahete, a sea-otter, a horned fish, a honeybee, a millet plant, and the hero Wenquath.” Bards are considered to be universally sacred, as are the oracles who inhabit the temples of Kho. And while the queen and high priestess is considered the most wise and powerful, it is the king who has direct control over the military.

The empire of Khokarsa is vast, spanning the two inland seas of ancient Africa (it cannot truly be called prehistoric Africa, as Khokarsa has written history). There are thirty queendoms in the empire, each ruled by its own high priestess. These cities bear outlandish names such as Dythbeth, Miklemres, Qethruth, Sakawuru, and Wentisuh.

Some of the cities along the inland seas, such as Kethna, border on the rebellious. Then there is the pirate stronghold of Mikawuru, which is outright defiant. Thus exists a complex system of interdependent trade, as well as a bountiful variety of localized customs.

Beyond the coasts, in regions seldom visited by the Khokarsans, lie the Wild Lands, filled with savage beasts and exotic peoples, including groups of paranthropoids, Neanderthals, and human-Neanderthal hybrids. On the edge of the empire, in a region known as the Western Lands, the aboriginal tribes have had limited contact with the Khokarsans over the centuries, but play an increasingly important role as the series progresses.

The Khokarsans themselves, Farmer explains in an addendum, are a people of mixed origins whose ancient ancestors lived as far away as Siberia, one ethnicity among them being distantly related to the Ainu of Japan.

It is against the carefully embroidered backdrop described above that Hadon of Ancient Opar begins. Hadon, the son of a disgraced numatenu (or honored swordsman), sets off in a galley from his home city of Opar, bound for the island of Khokarsa, located thousands of miles away on the north shore of one of ancient Africa’s inland seas.

There he is to compete in the Great Games, the winner of which will marry the queen and be declared king of the mighty empire. Hadon, though noble blood runs in his veins, is the common man.

It is only through his own resources and resiliency that he may hope to rise above the misfortunes of his family and become something greater. Together with his good-natured friend Taro and his powerfully-muscled nemesis Hewako, Hadon competes in athletic contests and bloodthirsty battles against the empire’s bravest heroes.

After competing in racing, the high jump, the high dive, boxing, wrestling, and tightrope walking over ravenous crocodiles, Hadon faces off with wild gorillas, bulls, and leopards. The barbaric spectacle in the coliseum of the Great Games rivals any of the gory blood sports we know from ancient Rome.

After competing in racing, the high jump, the high dive, boxing, wrestling, and tightrope walking over ravenous crocodiles, Hadon faces off with wild gorillas, bulls, and leopards. The barbaric spectacle in the coliseum of the Great Games rivals any of the gory blood sports we know from ancient Rome.

As Hadon sees his friends and fellow contestants die, he hears whispers that all is not well in the empire and slowly begins to wake up to the fact that the world is a more complex place than he could have imagined. Hadon of Ancient Opar is as much a tale of maturing youth as Farmer’s depiction of the sixteen-year-old Doc Savage in his novel Escape from Loki.

But Hadon learns quickly. He has not forgotten that it was plotting and politics that crippled his father and forced him to serve as a lowly sweeper of floors in the temple of Kho. The rumblings of King Minruth’s ambition to place Resu over Kho disturb the young hero. Still, Hadon’s youthful exuberance urges him on. After all, what nineteen-year-old male wouldn’t want to be king of an empire and husband to a beautiful queen?

Hadon of Ancient Opar is an epic in the true sense of the word. It is the beginning of the Hero’s Journey, the Campbellian mythological archetype. Our hero leaves his home, full of hope and testosterone, ready to conquer the world. When this exuberance begins to wear off, he would like nothing more than to refuse the call to adventure. But the oracle has decreed it.

Begrudgingly, Hadon accepts the task and crosses the threshold into the dangerous realm of the unknown. In the Wild Lands, he tests himself and finds his allies in the fair Lalila, her daughter Abeth, the manling Paga, the bard Kebiwabes, the guide Hinokly, and, most unlikely of all, his giant cousin Kwasin, exiled ravager of a priestess of Kho.

But that’s only the very beginning of the adventure, the rest of which can be found in Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa. I encourage readers interested in further exploring the world of Khokarsa to visit the Lost Khokarsa website, which features a wealth of information on the series, including exclusive material from Philip José Farmer’s literary papers.

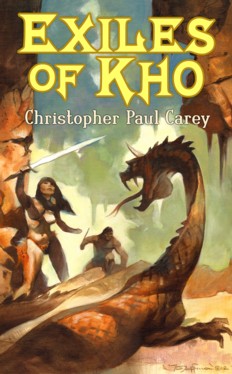

Readers of the trilogy may also be interested in a prequel story I wrote titled Exiles of Kho, due out later this year in a signed limited edition novella from Meteor House.

Readers of the trilogy may also be interested in a prequel story I wrote titled Exiles of Kho, due out later this year in a signed limited edition novella from Meteor House.

Two other authorized short stories set in Khokarsa I’ve written — “A Kick in the Side” and “Kwasin and the Bear God” (the latter based on an outline by Farmer) — are available, respectively, in the anthologies The Worlds of Philip José Farmer 1: Protean Dimensions (Meteor House, 2010) and The Worlds of Philip José Farmer 2: Of Dust and Soul (Meteor House, 2011).

Christopher Paul Carey is the coauthor with Philip José Farmer of Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa. He is an editor with Paizo Publishing and the award-winning Pathfinder Roleplaying Game, and the editor of three collections of Philip José Farmer’s work: Up from the Bottomless Pit and Other Stories, Venus on the Half-Shell and Others, and The Other in the Mirror.

His short fiction may be found in such anthologies as The Worlds of Philip José Farmer, Tales of the Shadowmen, and The Avenger: The Justice, Inc. Files. Visit him online at www.cpcarey.com.

[…] I figured wrong, because Subterranean Press has just released Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa, which is an omnibus of the two Ancient Opar novels by Philip José Farmer – Hadon of Ancient Opar (1974) and Flight to Opar (1976) – together with a third, new novel in the series, The Song of Kwasin, by Philip José Farmer and Christopher Paul Carey (Black Gate recently ran essays from Carey about the history of his remarkable collaboration with Farmer, and his discussion of Farmer’s ambitious creation, the lost civilization of Khokarsa.) […]

[…] I figured wrong, because Subterranean Press has just released Gods of Opar: Tales of Lost Khokarsa, which is an omnibus of the two Ancient Opar novels by Philip José Farmer – Hadon of Ancient Opar (1974) and Flight to Opar (1976) – together with a third, new novel in the series, The Song of Kwasin, by Philip José Farmer and Christopher Paul Carey (Black Gate recently ran essays from Carey about the history of his remarkable collaboration with Farmer, and his discussion of Farmer’s ambitious creation, the lost civilization of Khokarsa.) […]