Of Red Moon and Black Mountain and the Anxiety of Tolkien’s Influence

Red Moon and Black Mountain

Red Moon and Black Mountain

Joy Chant

Ballantine Books (268 pages, $0.95, 1971)

The shadow of The Lord of the Rings is long, indeed. In the 1960s Frodo lived and the reading public was hungry for more, and derivative works like The Sword of Shannara met that demand. This pattern continued into the 1980s with the publication of works like Dennis McKiernan’s Iron Tower trilogy, the series showing the clearest Tolkien “influence” of them all and one that literally provided more of the same. Now, this stuff wasn’t all bad; it filled a need and offered a safe, enjoyable formula. I willingly read many of these works back in the day and occasionally still do. But decades later many of the Tolkien clones haven’t aged all that well. I seem to have a lot less patience for them these days, even though I understand the environment in which they were written, and can appreciate that avoiding the influence of The Lord of the Rings 30-40 years ago must have been very difficult, if not impossible.

Take Joy Chant’s Red Moon and Black Mountain (1970). It’s well-written, not hackwork by any stretch. In 1972 the Mythopoeic Society bestowed its Fantasy Award upon the novel, denoting it as a work that best exemplified “the spirit of the Inklings.” Red Moon and Black Mountain has an unquestionable Tolkien-Lewis quality about it, if by spirit one means rewriting The Lord of the Rings with the framing device of The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe tacked on. After a solid start it descends into full-on Tolkien-clone, which probably explains why it’s largely forgotten today.

So what are the similarities between Chant’s novel and The Lord of the Rings? The names may look different, but the characters, races, events, and even the underpinnings of Chant’s world—the themes, the cosmological order of the gods, etc.—are largely identical to Middle-Earth. These include:

The Borderer, a combination of Strider with a dash of Bombadil. He’s a seeming lord among men in the wilderness and a remarkable tracker and forester. Men know him by many names; he is an exception to many rules. In him runs the blood of Garinna, a Starborn, who married a mortal man.

The Nihaimurh, a youthful, slender race of immortal wood-folk whose numbers have dwindled. In face and form they are youthful but their eyes are a thousand years old. They live in a wood called Nelimhon, banned to men, “fair but perilous,” an ageless place where time does not seem to pass.

The Nihaimurh, a youthful, slender race of immortal wood-folk whose numbers have dwindled. In face and form they are youthful but their eyes are a thousand years old. They live in a wood called Nelimhon, banned to men, “fair but perilous,” an ageless place where time does not seem to pass.

The Princess In’serinna , an amalgamation of Galadriel with a dash of Lúthien and Arwen. She is a member of the Children of the Stars; like Tolkien’s Elves a strange, proud, high race that requires little food and sleep, long-lived but sad beneath their outer gaiety. The Princess is one with tragedy: She wields the Star Magic in exchange for forsaking warmth forever.

Fendarl Kendrethon, onetime King of Bannoth, fallen Enchanter of the Star Magic and evil servant of the dark lord Ranid the Thrice Accurst. In Chant’s universe evil cannot create, but can only corrupt; Ranid and his evil servants are never destroyed, but can only be temporarily defeated. Ranid was one of seven loyal servants created to serve the One, the greatest of them, but was cast down and driven out after revolting against his Lord. See Sauron/Morgoth for more details.

A final battle that includes a lengthy mustering of the forces of good in the White City. A sample of Chant’s description of the event: “so the Swan of the Sea Kings was borne again into the north; and on the right of it went the Sea-horse banner of the Khentors, and on the left the nine-starred standard of the Enchanters. Close behind rode the Venduath, forty men and their captain, grey-clad and cloaked in royal green as shining dark as the holly of their banner.” And so on and so forth for two more pages. See the muster of Minas Tirith.

The White City itself, which is practically Minas Tirith with the serial numbers chiseled off the mortarwork. Chant describes it thusly: “And so Nicholas was the first to reach the White City. Just after dawn on the second day they sighted her, crowning the cliffs, catching the first light of the young sun, with clouds flying like banners of gray and gold above her. There were sea-swans rising from the waves and beating in before them, and the white towers shone, and he came at last to the fortress of Emneron the White, city of the Kirontin of old; the Pearl of the North, H’ara Tunij of the Sea Kings.” The only difference I can see is that Chant’s White City is ringed by four walls, not seven.

Probably the most blatant example of this Tolkien-ian influence is the presence of the entire Eowyn vs. the Nazgul scene, lifted out of The Lord of the Rings and placed whole and entire at the final battle of Red Moon and Black Mountain. Li’vanh (the boy Oliver) meets Fendarl on the field in front of the armies and drives his sword into his opponent’s ribs, only to be greeted with a sneer from the dark lord:

“Fools!” he cried. “Fools! Did you not know, had you not remembered that I cannot be hurt by any creature of this world? And though you send against me this foundling boy, yet what is bronze, or what is hammered iron, if not a creature of this world?”

Of course Li’vanh remembers Pippin’s Blade of Westernesse/aka his brother’s knife, which is of course not of this world, and thus Fendarl is vulnerable. You know the rest. Li’vanh is even struck with a “black sickness” after landing the fatal blow. I’m willing to write this scene off as good-natured homage; it shows less in the way of influence than a near 1:1 rewrite of the entire exchange on the Pelennor Fields.

Of course Li’vanh remembers Pippin’s Blade of Westernesse/aka his brother’s knife, which is of course not of this world, and thus Fendarl is vulnerable. You know the rest. Li’vanh is even struck with a “black sickness” after landing the fatal blow. I’m willing to write this scene off as good-natured homage; it shows less in the way of influence than a near 1:1 rewrite of the entire exchange on the Pelennor Fields.

Despite its lack of originality Red Moon and Black Mountain contains some worthy bits that make it an enjoyable read. For example, Chant does the high fantasy “tone” very well; if you like your fantasy with dialogue that sounds like this:

“Ah, by the Swans, my Lord Horenon,” she sighed, “I know not whether it is a mood of prophecy on me, or I am craven, but I feel a dread of this night’s work greater than any I have known before.”

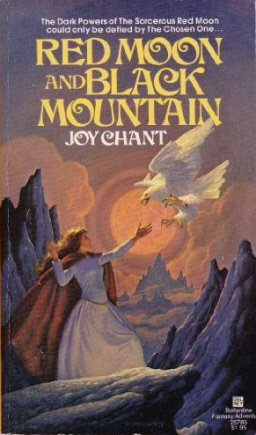

… then you may like Red Moon and Black Mountain. In addition, the sense of displacement—of entering and inhabiting a well-developed secondary world—is heady, and well done. The book opens with the siblings Oliver, Penny, and Nick Powell spirited away to the land of Vandarei in convincing fashion. In the ensuing chapters the children witness a stirring battle of black vs. white Eagles set against an otherwordly landscape (a second moon, blood red, rises against a charcoal black mountain). A mysterious Princess watches the swirling combat, poised on the precipice of a cliff, a metaphor for the importance of the battle in the skies and the knife-edge upon which its outcome rests.

But the originality of the work soon fades. We never actually learn the significance of this epic struggle of predatory birds, and the princess, seemingly set up to be a major figure, does not figure into the denoument of the story. Nor do the eagles. These elements take a backseat to Oliver, the chosen one who will decide the fate of Vandarei and deliver it from the clutches of the dark lord. Returning again to Tolkien Oliver can be viewed as a Frodo figure; in a moment of warring internal forces of fate and free will he offers his life to a greater cause, though not as a Ringbearer but a warrior who will meet Fendarl in single combat (though he does not know the way). Oliver’s fateful decision reads an awful lot like Frodo at the Council of Elrond:

But he had heard, and he knew, and he was alone in a moment grown deep and ringing, as if echoing to a great gong-note. He did not see the Council; he did not hear the voices. He saw only the choice before him, and heard only the unmistakable summons.

He stood up.

“Kirion!” he said loudly, interrupting in a voice hardly his own. “I am no creature of Khendiol, and men call me the Young Tiger. I think,” he said, his throat grown tight and dry, “that this fight is mine.”

In short, it’s as though Chant had the kernel of a good story with Red Moon and Black Mountain, but lost her way and returned to the safe and familiar confines of The Lord of the Rings.

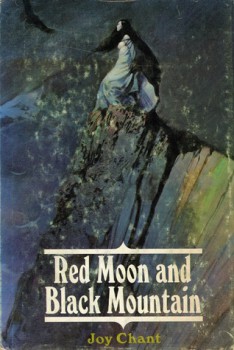

An outstanding quality of my particular copy of Red Moon and Black Mountain is its striking dust jacket, painted by arguably the greatest fantasy artist of all time, Frank Frazetta. As a full-blown Robert E. Howard fan who cut his teeth on The Savage Sword of Conan, I was sold on any book adorned with Frazetta artwork in the 1980s. Alas, the contents didn’t quite live up to the promise of its cover. Red Moon and Black Mountain isn’t a bad book, but it could have been so much more. While some will argue that it’s a good book in its own right, I view it as a casualty of the irresisitable pull of the immediate wake of Tolkien’s magnum opus.

I remember that book — I picked it up when I started collecting the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. Have you read any of her others? She wrote two more in the same world — When Voilha Wakes and The Gray Mane of Morning — and one Arthurian — The High Kings. I think Red Moon is the only one I’ve read myself.

Hi Joe, I’ve only read this one.

Then came Grey Mane of Morning, which is not like this at all, though it features the same children. It was wonderful.

It’s the best by far of the novel this author published. It packs the true mytic power of what it means to be the blood sacrifice.

Thanks for the comment, C-Foxessa. I have not read the others in the series and I’m glad to hear it sheds some of the heavy-handed Tolkien influence. To stress it here again, I think Red Moon and Black Mountain is quite well-written, just too derivative of The Lord of the Rings for my tastes. You can clearly see that Chant is a talented author.