The Borribles

The Borribles

The Borribles

Michael de Larrabeiti

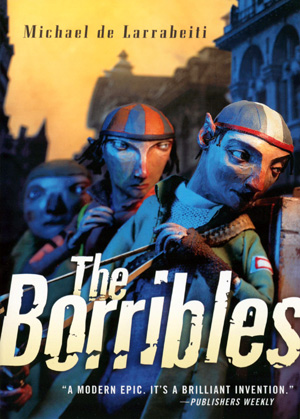

Tor (214 pp, $6.99, July 2005)

While on patrol one night in London’s Battersea Park, Knocker and his buddy Lightfinger discover a Rumble trespassing on their home turf. The two Borribles quickly capture the Rumble and then —

Wait. What’s a Borrible? What’s a Rumble?

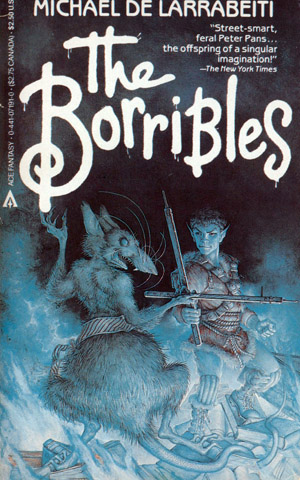

Borribles, in Michael de Larrabeiti’s razor-sharp novel, are “feral Peter Pans,” to cadge a phrase from the New York Times, pointy-eared children who never grow up:

Normal kids are turned into Borribles very slowly, almost without being aware of it; but one day they wake up and there it is. It doesn’t matter where they come from as long as they’ve had what is called a bad start. A child disappears and the word goes round that he was ‘unmanageable’; the chances are he’s off managing by himself. Sometimes it’s given out that a kid down the street has been put into care: the truth is that he’s been Borribled and is caring for himself someplace.

They are urchins gone elf, living in loose neighborhood tribes, squatting in abandoned buildings and shoplifting their food; they have no leaders or laws beyond a collection of proverbs (“Don’t get caught”), which they frequently cite in their arguments. Borribles are anarchist lawyers, “outcasts, but unlike most outcasts they enjoy themselves and wouldn’t be anything else.”

Their sworn enemies are the Rumbles, intelligent rodents resembling “a giant rat, a huge mole or a deformed rabbit” that walk on hind legs and even drive cars. The Rumbles dwell in a massive (and very posh) underground bunker in Rumbledom; a native Londoner might better recognize the area as Wimbledon Common. They’re also parodies of The Wombles, a series of children’s books, TV shows, and films which I’ve never read or seen.

The discovery of a Rumble rooting around in their territory incites suspicion of a Rumble invasion of Battersea and beyond. A Borrible council is quickly called, whereupon it’s decided each of the Borrible tribes of London will furnish a warrior to participate in the Great Rumble Hunt. The goal of this expedition: to infiltrate Rumbledom and assassinate the eight members of the Rumble High Command, thereby decapitating Rumble society. And, so that the Rumbles may have a sporting chance, the Borribles release the Rumble prisoner with a message for the High Command, explaining the entire plan.

Thus ends Chapter One.

It is difficult to express how much I love The Borribles. Originally published in 1976, I first read it in the mid-80s. Some thirty years later, I stumbled upon the Tor Teen reprint series and recently read it to my sons. Its fast pacing and anti-authoritarianism (the Borrible culture only runs into trouble once it begins deferring to bosses) reverberate with me still. Bookstores had no Young Adult genre in days of yore; you had Narnia in one dusty back corner and the grown-up sci-fi/fantasy section in the other. This is where The Borribles was solidly shelved. It’s very much a Cold War novel — there’s some John le Carré moral equivalency that I failed to fully appreciate before — and in the Year of Our Lord 2012 the very Englishness of it refreshes: the Rumble prisoner taunts his captors as “street Arabs;” Knocker responds by calling him a “twat.” And what my tween self had interpreted as a cliffhanger ending — for years I searched for the sequel The Borribles Go For Broke to learn what happened — I now see was a Pyrrhic finish. The Borribles is a complete novel in itself, a Londonized Nordic saga: there is a sea voyage and a raid and a skaldic ethos but also, ultimately, a Ragnarok.

It is difficult to express how much I love The Borribles. Originally published in 1976, I first read it in the mid-80s. Some thirty years later, I stumbled upon the Tor Teen reprint series and recently read it to my sons. Its fast pacing and anti-authoritarianism (the Borrible culture only runs into trouble once it begins deferring to bosses) reverberate with me still. Bookstores had no Young Adult genre in days of yore; you had Narnia in one dusty back corner and the grown-up sci-fi/fantasy section in the other. This is where The Borribles was solidly shelved. It’s very much a Cold War novel — there’s some John le Carré moral equivalency that I failed to fully appreciate before — and in the Year of Our Lord 2012 the very Englishness of it refreshes: the Rumble prisoner taunts his captors as “street Arabs;” Knocker responds by calling him a “twat.” And what my tween self had interpreted as a cliffhanger ending — for years I searched for the sequel The Borribles Go For Broke to learn what happened — I now see was a Pyrrhic finish. The Borribles is a complete novel in itself, a Londonized Nordic saga: there is a sea voyage and a raid and a skaldic ethos but also, ultimately, a Ragnarok.

It’s this philosophical depth that bowls me over. The book is nonstop action, but occasionally the characters pause to reflect. With no interest in money (maybe) or romantic love (maybe) and eternity spread like a clean tablecloth before them, Borribles are obsessed with doing stuff, with having adventures they can endlessly retell later. Every Borrible must have an adventure before receiving his or her name and so the eight volunteers for the Great Rumble Hunt are nameless. They are temporarily given the names of their assigned victims on the High Command, which will only become permanent if their work is successful. Knocker — eager to earn a second name — ostensibly accompanies the expedition as its historian. Borribles don’t fear death nor do they seem to believe in a next world; and this optimism, this drive to burn their candles brightly in this lifetime, produces wonderful exchanges like this:

“It’s funny in a way, isn’t it?” said Stonks. He stopped crawling and faced his companion. “Going after a bloke with the same name. It’s like going after yourself. I mean, the names we’ve got aren’t our names, they’re really theirs; but when we’ve eliminated them, the names will be ours for ever, and the adventure we’ve had, even if we’ve been killed, can never be taken away.”

“It’ll be taken away if we’re all killed and nobody gets back to tell the story. If it’s never written down, then it’s gone for ever. The story’s the thing; have you thought of that?”

“Yeah, maybe Knocker shouldn’t have come this far. He can’t be Historian if he’s captured or killed… You know, I hadn’t realized Historians were so important.”

Torreycanyon held Stonks by the arm for a moment.

“Ah,” he said, “but if he hadn’t come this far he would have had no story to tell. Historians have to go where the history is, I s’pose.”

De Larrabeiti died in 2008 but like Knocker his stories will long survive him. His wit — cynical toward authority and hierarchy, sentimental toward persons and friendship — and individualist message should be shared as widely as possible, like a Borrible adventure told on a cold night around a drum-barrel fire. Read this book.

And, oh — don’t get caught.

I’ve heard about this one for a long while, but now i must hunt it down. Good stuff, Jackson.