The Big Barbarian Theory

Conan, King Kull, Cormac, Bran Mak Morn — characters often imitated, never duplicated. These creations of Robert E. Howard started the sword-and-sorcery boom of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Conan, King Kull, Cormac, Bran Mak Morn — characters often imitated, never duplicated. These creations of Robert E. Howard started the sword-and-sorcery boom of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Then there are the barbarian warriors inspired by Howard — Clonans, as one writer recently referred to these sword-slinging, muscle-bound characters.

A fair observation, but in some cases, not so true.

We prefer to think of these tales of wandering barbarian heroes as “Solo Sword and Sorcery” because the majority of these characters are lone wolves, without sidekicks or even recurring companions. This is a big part of their appeal, in fact.

We’ve read many, if not most, of the Conan pastiches, including the novels based on Howard’s other creations. Karl Edward Wagner’s, Poul Anderson’s, and Andy Offutt’s portrayals of the Cimmerian come within a sword’s stroke of Howard’s vision.

L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter, in commodifying the character, arranged the long, informal saga of Conan in chronological order and, by extenuating these adventures with dozens more, made of Howard’s original vision a long-form series similar to the episodic success of a television show on a prolonged run of diminishing returns.

For some readers, however, the advantage of this development is that it provided a sort of character arc as Conan grows from a youth to an older man.

That said, however, it is better to read the Conan tales in the order in which Howard wrote them.

By doing this, we gain at least two things: the sense of an adventurer’s life being recounted in the same haphazard way that it was lived, and — perhaps more importantly — we witness Howard’s own developing arc as a writer — his growth, his maturity, his mastery of the art of storytelling.

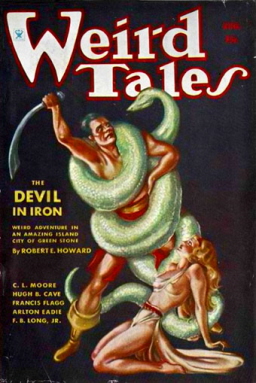

We also get to watch as Howard becomes more sharply attuned to his markets, as Conan the commercial property evolves from the regal lion of “The Phoenix on the Sword” and the dangerous young buck of “The Tower of the Elephant” to his later portrayals as a lusty roustabout and badass, soldiering and womanizing, carousing and drinking, fighting and fighting some more — and, more often than not, attaining that month’s Weird Tales cover with a Margaret Brundage beauty in bondage.

We also get to watch as Howard becomes more sharply attuned to his markets, as Conan the commercial property evolves from the regal lion of “The Phoenix on the Sword” and the dangerous young buck of “The Tower of the Elephant” to his later portrayals as a lusty roustabout and badass, soldiering and womanizing, carousing and drinking, fighting and fighting some more — and, more often than not, attaining that month’s Weird Tales cover with a Margaret Brundage beauty in bondage.

But the endless parade of pastiches shares much of the blame for the death of the Big Barbarian Solo craze of the late 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s.

In addition, in a period of historic social change, many of these tales betrayed an attitude that was falling out of favor. The limitations apparent in this go-round of sword-and-sorcery fiction were not challenged, and most of the pastiches predictably moved along a preordained path with a one-dimensional, exaggeratedly masculine character going through rote episodes no more compelling than the umpteenth rerun of a grade C Western movie.

Furthermore, the audience for these stories grew older and turned to other distractions — video games, primarily, because the technology had reached an advanced level of sophistication, as well as comic books and summer blockbuster movies, which were available for rewatching on VHS and, later on, DVD.

The demise of the one-dimensional big barbarian lunkhead at that historical moment was deserved.

In 1970, Joe wrote a letter to Lin Carter, who was then the editor of Ballantine Books’ Adult Fantasy Series. Joe asked how to go about submitting a Conan novel he had written.

In 1970, Joe wrote a letter to Lin Carter, who was then the editor of Ballantine Books’ Adult Fantasy Series. Joe asked how to go about submitting a Conan novel he had written.

Lin Carter was nice enough to reply quickly, telling Joe that only he and L. Sprague deCamp were licensed to write Conan stories.

He suggested, however, that Joe change the name of Conan to one of Joe’s own choosing and change any other names borrowed from Howard, then submit the novel to a publisher as his own original creation.

In other words, Joe was advised to write a Clonan novel.

It was this disgraceful attitude that Conan was interchangeable with other barbarian heroes that Joe didn’t care for. (A Conan-clone by any other name is still Conan?)

Oddly enough, it was shortly after this response from Lin Carter that Bjorn Nyberg’s Conan pastiche appeared on the scene. Then, as we know, other writers were brought in as “hired guns” to continue the Conan saga — and, so often happens in the wake of hired guns, there was trouble: we saw the slow death of the Barbarian Solo brand of sword and sorcery.

Thankfully, Howard’s Conan did not fall victim to these troubles and vanish from the scene. This is a tribute to Howard’s brilliance and strength as a writer as well as to his devoted audience, who know that there is much more to Howard, and to Conan, than beefsteak and sword point.

These fans and editors championed Howard’s work to keep him in print, ultimately in revised, corrected editions.

The first wave of the Barbarian Solo sword-and-sorcery boom was actually rather short-lived. It lasted from roughly the mid 1960s to around the early 1980s.

But it gave us a roster of wonderful writers such as Richard L. Tierney, Ted (T. C.) Rypel, David Drake, the late David Madison, Charles Saunders, Tanith Lee, and Diana L. Paxson.

But it gave us a roster of wonderful writers such as Richard L. Tierney, Ted (T. C.) Rypel, David Drake, the late David Madison, Charles Saunders, Tanith Lee, and Diana L. Paxson.

(Joe would add David C. Smith to this group, as well.)

After that, as the popularity and success of epic fantasy spawned numerous series of multivolume sagas, the old-school brand of sword and sorcery all but disappeared. Many publishers shied away from the “barbarian thing.”

There are several reasons for this, and not all of them due to the one-dimensionality of many of the characters promoted in sword-and-sorcery novels. David G. Hartwell explained it best in Age of Wonders (originally published in 1984, revised and reprinted in 1996).

In Age of Wonders, Hartwell discusses the business of publishing science and fantasy during this period. In Appendix V, “Dollars and Dragons: The Truth About Fantasy,” which originally appeared in The New York Times Review of Books, Hartwell discusses how unfashionable fantasy fiction became in the postwar years compared with the first half of the twentieth century, when it was commonplace (think of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, by James Thurber, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, by R. A. Dick [Josephine Aimee Leslie] and the Mr. Ed stories by Walter R. Brooks).

In the 1950s and early 1960s, fantasy was regarded as young adult fiction (consider A Wizard of Earthsea, for example). This attitude changed, Hartwell notes, “in terms of category publishing, with J. R. R. Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings trilogy.”

As we know, LOTR became an astounding cult classic in the late 1960s into the 1970s. Its success encouraged Ian Ballantine to launch the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series in the late 1960s, bringing back into print George MacDonald, William Morris, Evangeline Walton, E. R. R. Eddison, and Mervyn Peake, among others.

To the “consternation” of the champions of this type of Old World, high art fantasy, however,

To the “consternation” of the champions of this type of Old World, high art fantasy, however,

Only the Conan the Barbarian series from Lancer Books caught on… Associated series, such as Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series and Michael Moorcock’s Elric series, rode the crest, too. Barbarian fantasy sold, and it was the conventional wisdom that it sold to teenage readers, not to the wider Tolkien audience.

Ballantine found a way to reach the Tolkien readers when Lester del Rey, then a consulting editor for the publisher, read the manuscript of The Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks.

The strategy, Hartwell explains, was this:

They would take this slavish imitation of Tolkien by an unknown author and create a best-seller using mass-marketing techniques, and so satisfy the hunger in the marketplace for more Tolkien.

Following the success of The Sword of Shannara, del Rey founded his own fantasy imprint and moved forward with his line of written-to-order, mass-marketed, Tolkienesque/Shannaraesque fiction:

The books would be original novels set in invented worlds in which magic works. Each would have a male central character who triumphed over evil (usually associated with technical knowledge of some variety) by innate virtue, and with the help of a tutor or tutelary spirits. Mr. del Rey had codified a children’s literature that could be sold as adult. It was nostalgic, conservative, pastoral, and optimistic. One critic, Kathryn Cramer, seeking an explanation for why an American audience would adopt and support such a body of fiction, has remarked that it was essentially a revival of the form of the utopian novel of the old South, the plantation novel, in which life is rich and good, the lower classes are happy in their place and sing a lot, and evil resides in the technological North. The plot is the Civil War run backward. The South wins. That pattern seems to fit a majority of recent fantasy works well.

By the late seventies, the success of the del Rey formula was so confirmed that many other publishers began to publish in imitation. Dragons and unicorns began to appear all over the mass-market racks, and packaging codes with proper subliminal and overt signals developed. A whole new mass-market genre had been established. One can understand it best in comparison to the toy market’s discovery that you can sell dolls to boys if you call them action figures and make them hypermasculine.

In this way, “barbarian” sword-and-sorcery fiction, which has its roots in the masculine adventure of the early twentieth-century pulps, combined with the Gothic and horror elements that had become so popular in fiction magazines of the late 1920s into the Depression, was succeeded commercially — and very profitably — by juvenilia promoted as adult fiction.

At the same time, some of the old guard who had written Golden Age (1930s and 1940s) and Silver Age (1970s and 1980s) old-school sword and sorcery passed away, retired, or just moved on to new territory — John Jakes, for example, and even Michael Moorcock, who became involved with the British band, Hawkwind.

These writers, as well as Fritz Leiber and Jack Vance, to name a few, in fact had written, not Big Barbarian Solo sword and sorcery, but literate adventure-fantasy fiction that helped develop and expand the genre.

One of the elements that often bothered us about sword and sorcery was its frequent lack of complex or developed characters, engaging dialogue that propelled the story and brought the characters to life, and the lack of real human drama and tragedy — the kind of plotting and drama we find in all good storytellers, from Shakespeare to Dickens and other great novelists.

Dramatis gravitas — that’s what the Big Barbarian Solo tales lacked. They were simple, straightforward action/adventure tales.

Most of them were not meant to be more than that, of course, and that is in the grand tradition of some of the best pulp fiction. And yet… the possibilities are there.

Most of them were not meant to be more than that, of course, and that is in the grand tradition of some of the best pulp fiction. And yet… the possibilities are there.

Thankfully, a new sword-and-sorcery boom has been underway for quite some years now. With a growing female audience, dedicated publishers, and an influx of daring young writers — including many gifted women who are bringing something new to the genre — the sword-and-sorcery genre is at last growing and flourishing.

Thanks to such venues as Black Gate magazine, Rogue Blades Entertainment, Pyr Books, and the whole gladiatorial arena of self-publishing houses… thanks to such writers as Howard A. Jones, Milton J. Davis, Cynthia Ward, Jon Sprunk, Kate Martin, Bruce Durham, Christopher Heath, and a legion of others… sword-and-sorcery is alive and well and growing up at last.

The Big Barbarian may be wearing new clothes and have a more cultured attitude, but he’s still out there — and she’s still out there — continuing to fight the good fight, slaying demons and wizards and monsters and plain old-fashioned nasty villains.

And if there are any other writers out there we have failed to mention, we apologize… in the name of Crom!

Thanks, John! Once again, a splendid job in setting up our article and posting it in such elegant fashion. Always a thrill and a real pleasure to contribute to Black Gate’s website.

— Joe Bonadonna, author of MAD SHADOWS: THE WEIRD TALES OF DORGO THE DOWSER

NIce theory: plenty of insight, concisely put! 🙂

Thank you, carlaz!

You’re welcome Joe (and Dave).

A splendid article all around. Exactly the kind of thing I like to see on the BG website.

“Exactly the kind of thing I like to see on the BG website.” Me too — Let’s see more of it everywhere!

Thanks, Jason!

Interesting post. I particularly like the way you phrased this:

“In this way, “barbarian” sword-and-sorcery fiction, which has its roots in the masculine adventure of the early twentieth-century pulps, combined with the Gothic and horror elements that had become so popular in fiction magazines of the late 1920s into the Depression, was succeeded commercially — and very profitably — by juvenilia promoted as adult fiction.”

I’d say that this trend has continued, except that the pretenses have been dropped….Harry Potter, Twilight, etc.

Today we see far too much emphasis on characterization in the genre. A character’s sock preference isn’t interesting and I certainly don’t want my barbarian heroes to be feminized 21st Century Western men. There is still a huge market out there for masculine adventure stories and the success of reprints of early 20th Century adventure stories from the likes of REH is telling (thank you Mr. Jones for helping bringing Harold Lamb back into print!).

Thanks, everyone! Dave and I are proud of this article, and proud that it’s up on BG’s website. We were hoping to add a little insight to the genre, look at it from a historical perspective, and trace its roots. We had been away from the genre for some years, and we returned almost at the same point in time. It was a delight to find the Sacred Genre alive and well and thriving — something that was not always reflected by the books I saw on the shelves of Borders, and Barnes&Noble. So I spent my time at used bookstores. Now I know better, and the selection is wide open.

Giga-Rad article. Thrilled to see something so starkly Sword + Sorcery posted.

I like your idea about Leibers’ contributions, though I have always maintained Leiber is the first ‘true’ Sword + Sorcery writer.

Leiber analysed (thus ‘corrected’) the works of Howard before him and consciously methodically set out to make his ( Leibers’ own not Howards’ ) vision a reality in print.

In that sense Leiber as a respectful, though individual writer knowingly followed Howard down a previously unseen path.

I don’t think Howard really saw the path he was walking.

Vance I think is more like Howard in spirit than Leiber.

Howard didn’t know he was a lightning flash of manic originality and sheer unconscious pioneering. He was too busy serving his own ends to ‘think’ about his greater impact, not unlike Conan himself, Howard is an anti-hero.

Sheenan’s tits! You should be sorry for not mentioning KEW.

You make valid points, Radiant Abyss. I agree. But we did mention KEW.

Karl Edward Wagner is the second author mentioned — right after REH.

And that’s why your the Editor and Chief, Chief.

Irregardless of my blinding loyalty to KEW spiked by insomnia induced dyslexia I am a bit taken aback that my opinion on Sword + Sorcery didn’t get more of a stir.

Oh well bonus points from me Bonadonna + Smith for mentioning Vance and ( Clark Ashton )Smith.

I deducted points from myself because I’m just seeing these Comments now, as I prepare to share this article again on Facebook. Either I missed or never received the “pingbacks.”

Very illuminating. I’d never heard of that Hartwell piece–thank you especially for discussing the business history behind all these shifts in the genre.

I think the idea of apologizing in the name of Crom would move Conan to gigantic mirth. It certainly did me.

Great stuff. You’ve given me more names and titles to add to my personal Sword and Sorcery Syllabus.

Thank you, Sarah!

“Vance I think is more like Howard in spirit than Leiber.”

Hmmm, can’t really agree that Vance is much like Howard. The swashbuckling, heavily-muscled barbarian is not a Vance hero. Vance’s central characters are usually young men who triumph over evil thanks to brains and competence, not brawn.

“Vance I think is more like Howard in spirit than Leiber.”

In spirit. Not flesh/substance/surface.

Nigh unkillable, nearly seven foot, death-dealing, mighty thewed wildmen, is not the spirit/underworld/hidden/shadow of Howards’ Conan series.

That is surface.

Both Howard and Vance had no idea they were going to be held up as sages showing the unseen path to new sub-types of adventure fiction.

They just wrote adventure fiction ( cause they liked it, and they could sell it ). Vance and Howard were just mercs, that happened to be made of better stuff than the folks selling themselves as ‘more than writers for fun and profit.’

Everything Vance and Howard did/does has a sub layer of…ADVENTURE! For it’s own sake.

No one reads Vance or Howard for the mighty thewed plotting.

It’s the mighty thewed ADVENTURE! That is the goal.

They had/have both said so several times.

And both didn’t/don’t give a shit if anyone thought/thinks their characters or plots were anemic. Not only did/do they know that’s probably the popular opinion, that’s not the their personal goal with the work, beyond selling it to the highest bidder that could give them the widest audience.

Clear things up any?

No, you have obscured things more than clarified them.

I don’t agree that “ADVENTURE for it’s own sake” is the best way to characterize Vance. A great many of his books are better described as mysteries, even if they are in a science fiction or fantasy setting. Solve a crime or conundrum, find something missing, hunt down and punish a malefactor — these are the persistent themes in (for example) the Cadwal Chronicles, the Lyonesse series, the Demon Princes series, the Alastor series, the Durdane Series, Night Lamp, The Last Castle, The Languages of Pao, among others (not to mention in short stories like The Moon Moth and Chateau D’If). It is no coincidence that Vance wrote a dozen or so crime/thriller novels in addition to his fantasy / SF works!

In Vance’s novels, the excitement and physical danger is not the central theme as in Conan-esque “adventure” novels; often, the protagonists seek to avoid excitement and physical danger! The central theme is solving a problem, more often than not through the use of intelligence, logic, and competent action.

Needless to say, none of Vance’s books have an “anemic” plot, and if that is the characteristic of “adventure” novels, then Vance is certainly not an adventure novelist.

Howard’s plots are only ‘anemic’ compared to the bloated monstrosities on the market today. Howard was able to put together a coherent, satisfying, and conclusive plot in just a few pages. Some living fantasy writers (popular ones) can’t accomplish the same in a few books.

Thank you, sirs, for the sharp look at where S&S has been, where it went and where it’s going. Fascinating look at the field from someone on the 70’s frontlines.

Thank you, the wasp!

Lugo –

Vance wrote adventure fiction, if we can say that such a type of fiction exists and Vance wrote anything classifiable.

Dude has series HE titled; Planet of Adventure.

Vance had said about the Demon Princes series that he didn’t really care to explore the motive of revenge, but to use revenge as an excuse to explore the stars. ADVENTURE!

Admittedly Vance will tack something onto the surface of his adventure fiction so that folks think there is some ‘purpose.’

There really isn’t often with Vance, other than a single pointed direction of energy towards new experience. Adventure?

Howard was often less than this polite, but there again this single pointed direction of energy to NEW experience, is underneath most of both writers works.

Tyr –

I hope you don’t believe I think that Howards’ plots are ‘anemic’ myself.

I quite like Howards’ sparse, focused, need-to-know, plotting.

Howards’ characterization is bar far the least understood aspect of his works.

Someone should do a series of blogs on how REH maybe doesn’t bite that hard in the character dept.

Oh well…

Characterization is key in any genre. REH was subtle and very effective in his characterization of Conan. Many people don’t see or discuss that. I’ve always felt that only REH could write Conan – although a few writers did come close. The big difference between Conan and the likes of Thongor, Kothar, Brak and company is that they were only shadows of Conan.

[…] and Joe’s last collaboration for us was The Big Barbarian Theory, one of the most popular articles on the Black Gate blog last year. We featured David’s The […]

[…] The Big Barbarian Theory […]