Lost Classics of Pulp: Guy Boothby’s Dr. Nikola and Pharos the Egyptian

One doesn’t have to dig very far to discover my devotion to the works of Sax Rohmer. Peter Haining was, I believe, the first commentator to propose that Australian writer Guy Boothby’s works were a likely influence on Rohmer in the excellent survey, The Art of Mystery and Detective Stories. I first stumbled upon Boothby’s name and that of his most famous creation, Dr. Nikola courtesy of Larry Knapp’s brilliant Page of Fu Manchu website. Finally, it was a very informative piece written by that eminent Sherlockian, Charles Prepolec that convinced me I had to read the Nikola series for myself.

One doesn’t have to dig very far to discover my devotion to the works of Sax Rohmer. Peter Haining was, I believe, the first commentator to propose that Australian writer Guy Boothby’s works were a likely influence on Rohmer in the excellent survey, The Art of Mystery and Detective Stories. I first stumbled upon Boothby’s name and that of his most famous creation, Dr. Nikola courtesy of Larry Knapp’s brilliant Page of Fu Manchu website. Finally, it was a very informative piece written by that eminent Sherlockian, Charles Prepolec that convinced me I had to read the Nikola series for myself.

Five Nikola books were published between 1895 and 1901. The best editions available today are in the two-volume The Complete Dr. Nikola published by Leonaur Press. Dr. Nikola is a criminal mastermind with an occult twist. Think Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarty (introduced only one year before Nikola) eerily anticipating Aleister Crowley and you have a pretty good idea of Boothby’s ambitions.

Like much fantastic fiction of the Victorian era, the books are more about how others fall into Nikola’s web than they are about the sinister doctor himself. This was the same approach taken by Bram Stoker with Dracula and Rohmer with his Fu Manchu series. The Nikola books are also globe-trotting adventures that move rapidly from Australia to Europe to Egypt to London to Africa to Tibet. The sense of mystery that pervades these exotic settings in those imperialist days of empire-building is part of the books’ nostalgic appeal today.

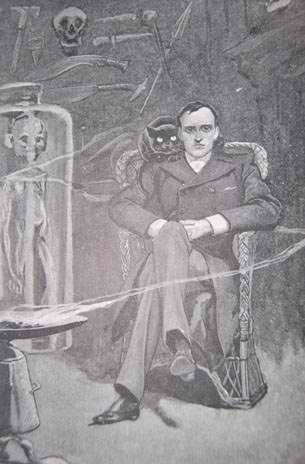

Boothby was not a cautious writer and his narratives are littered with inconsistencies in dates or ages of characters. Nikola himself is so compelling whenever he takes center stage in each book that one easily forgives such flaws. The brilliant, but decidedly amoral scientist is a man of small stature and slight build with an intense look. The description of his features, the near psychic power that compels characters to hold his gaze, and the ever-present black cat that rests upon his shoulder certainly evoke both Dr. Fu Manchu and Ian Fleming’s Ernst Stavro Blofeld. A younger generation weaned on Austin Powers will likely never fully appreciate how this remained a potent image of perverse villainy as recently as the 1960s.

Nikola’s laboratory with its many exotic insects and strange creatures suggesting genetic experimentation also reads as a near match to the very words Rohmer would use to describe Fu Manchu’s laboratory in several entries in the longrunning series written in the 1930s. Of course, Fu Manchu would never bother with a cat, but his pet marmoset is frequently described as perching on the Devil Doctor’s shoulder in the same fashion as Nikola’s black cat.

Nikola’s laboratory with its many exotic insects and strange creatures suggesting genetic experimentation also reads as a near match to the very words Rohmer would use to describe Fu Manchu’s laboratory in several entries in the longrunning series written in the 1930s. Of course, Fu Manchu would never bother with a cat, but his pet marmoset is frequently described as perching on the Devil Doctor’s shoulder in the same fashion as Nikola’s black cat.

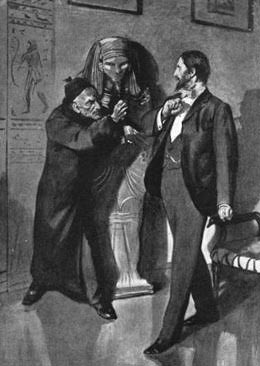

What I was completely unaware of until recently (thanks, once again, to the erudite Mr. Prepolec) was that Boothby created a second literary villain who likewise reinforces the theory that Rohmer was an avid reader of Boothby’s work. The secondary figure is the title character in Boothby’s 1899 novel, Pharos the Egyptian. Pharos is a wizened old Egyptian with an ever-present pet monkey called Ptahmes. Like Nikola, Pharos is of slight build but possessed of an uncanny charisma and psychic powers more advanced than Nikola himself.

The thrust of the first part of the book involves Pharos’ efforts to retrieve the mummy of Ptahmes (whom his pet monkey is named after) from the narrator who inherited the sarcophagus from his late father, a renowned Egyptologist. The historical Ptahmes is the magician that Pharoah pitted against Moses in the Book of Exodus. Ptahmes was defeated by Moses and blamed for the subsequent curses of Pharaoh visited upon Egypt (and ripe for exploitation by William Goldstein’s Dr. Phibes a few thousand years later). Ptahmes was buried alive and cursed to walk the earth as an immortal. Unsurprisingly, it transpires that Pharos is not a servant of or even the reincarnation of the legendary magician, but rather the immortal Ptahmes himself. The monkey apparently functions as some sort of familiar for Pharos’ occult powers in the same fashion as Nikola’s black cat.

Much of the thrust of the narrative involves the narrator, Cyril Forrester, a renowned artist in his obsessive pursuit of the beautiful and strangely exotic figure of the gifted musician, Valeric de Vocxqual, Pharos’ ward. Of course, Pharos’ hold on his beautiful and tragic young ward is far from normal. Readers of Sax Rohmer’s earliest Fu Manchu thrillers will be reminded of Dr. Petrie’s pursuit of Karamaneh who was similarly held enslaved to Fu Manchu’s irresistible will.

Much of the thrust of the narrative involves the narrator, Cyril Forrester, a renowned artist in his obsessive pursuit of the beautiful and strangely exotic figure of the gifted musician, Valeric de Vocxqual, Pharos’ ward. Of course, Pharos’ hold on his beautiful and tragic young ward is far from normal. Readers of Sax Rohmer’s earliest Fu Manchu thrillers will be reminded of Dr. Petrie’s pursuit of Karamaneh who was similarly held enslaved to Fu Manchu’s irresistible will.

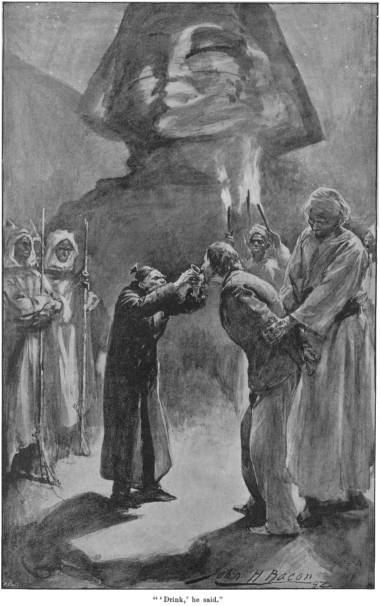

The character of Pharos is at his finest when he delights in the ruination of others that he has carefully cultivated. A truly Satanic figure, he first appears chuckling while one of his unfortunate victims drowns himself in the depths of despair. At its most outré, the book offers the sight of Pharos cowering in his preternatural fear of storms while on water or of Forrester or Valeric time-slipping (literally traveling to centuries past under Pharos’ direction via a dream-state).

Pharos’ main plot involves unleashing a deadly virus that decimates the Western world for its defilement of Egyptian burial sites. It takes Forrester an inordinate amount of time to work out that he is the carrier of the disease as he travels the world marveling as others fall dead around him. It takes even longer for him to work out that he holds the key to the antidote. Boothby frustrates the reader during these passages and in his dissatisfying failure to tie up all of the loose ends at the end of the book apart from suitably dispatching his villain. Even more confusing is the fact that Boothby apparently loses sight of his prologue which promises a rather different ending than the one he delivers.

Still, such weaknesses aside, this is a compelling reading and thanks are due to Wildside Press for making this rare gem available once more. The book is highly recommended to Sax Rohmer fans, lovers of pulp fiction, and those interested in the development of occult fiction or the criminal mastermind thriller sub-genre. Here’s hoping that some enterprising publisher gets his hands on Boothby’s 1902 occult thriller, The Curse of the Snake and makes it available once more. For all his failings, Boothby’s compelling villains, exotic settings, and critical view of British imperialism make his fiction readable more a century after his works passed into obscurity.

William Patrick Maynard was authorized to continue Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu thrillers beginning with The Terror of Fu Manchu (2009; Black Coat Press). A sequel, The Destiny of Fu Manchu will be published April 2 by Black Coat Press. Also forthcoming is a collection of short stories featuring an original Edwardian detective, The Occult Case Book of Shankar Hardwicke and an original hardboiled detective novel, Lawhead. To see additional articles by William, visit his blog at SetiSays.blogspot.com

Good on Wildside Press. I can only hope that many years hence, when I’m long gone and my work is in the public domain, there’s a publishing outfit that can connect it with a new generation of readers–in whatever medium people use then.

[…] the pulp fiction at the turn of the century I discovered that there was a villain called Doctor Nikola. I hope in this century that I (Father Nikola) make a more positive impact on the Church and the […]