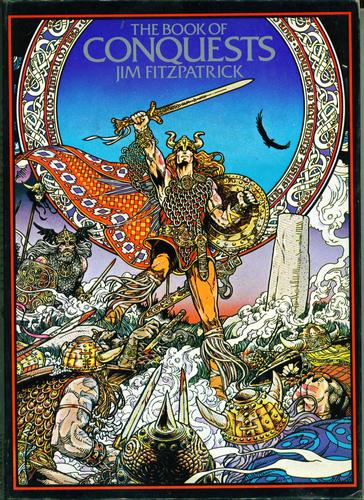

INVADING FANTASY

CONQUER THIS

Lebor Gabála Érenn — it just rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it? Literally: “The Book of the Taking of Ireland” or, as it’s usually rendered in English: “The Book of Invasions”, or even, “The Book of Conquests”. It’s a medieval history in case you hadn’t guessed. A full and not very frank account of every event that ever happened on the island of my birth.

People love to visit Ireland, apparently, and it’s even more fun when you bring an army with you. They’ve all done it, every horde and its crazy gods: Patholonians, Fomorians, Nemedians, Belly Men, The People of the Goddess Danú (who later fled underground to become the Sidhe) and *finally* — drum roll — The Gaels.

I say “finally”, because that’s where The Book of Invasions ends, but just as WWI didn’t quite live up to “the War to end all wars”, and the unification of Germany failed utterly to “end history”… well, Ireland’s attraction for blood-thirsty tourists only got stronger after that.

A PERSONAL INTERLUDE WITH SOME NUDITY

I took a cycle today. Up the twisty road, past the scary dog and all the way to the ruins of a church shattered by Cromwellian soldiers. Under the soil of a nearby field, lie the foundations of the rebellious castle that had attracted the English invaders in the first place.

Down the hill again I went, and after, while undressing my fabulous body in front of the open window of my bedroom, I could see a magnificent Round Tower that the supposed final Conquerors had built to protect their treasures from invading vikings. Sometimes the defences worked, but where the Danes failed, the next invaders — the Normans — saw more success. They attached a church to the tower, and the surrounding cemetary has been so crowded with conqueror and conquered alike that the level of the soil in which all are buried has risen and risen until it has swallowed most of the lower windows entirely.

YOU ALREADY KNOW BIT AND WILL RESENT BEING TOLD

History, as you already know, comes in layers, and all of them are still with us, all of the time and all at once. Now, if you’re a writer of fantasy, right here’s the point where you’ll expect me to harrangue you about how you should fill your stories with these layers — just like the boys at the top of the class did: JRRT and GRRM. And you probably should. It will make your world feel more “lived in”, rather than a construct that came into being just so your Dwarves have somewhere to dig and your bears had some woods to urgently visit.

Layering adds mystery and magic for very little cost. I don’t know about you, but I can never pass a ruin in real life, or even in a book, without wondering who lived there and what became of them. The bored farm-boy*, stabling his cows in the castle, is walking on the graves of warriors and queens — his own ancestors. The walls hold the bones of the slaves who built them, themselves former royalty, former conquerors, and their blood too, runs in the boy’s veins.

He’s no different from any of the rest of us. I myself have an Irish version, of an English version of an Irish version of a Viking name. I’m a product, genetically as well as culturally, of every invasion my country has ever known. So far. Of economic migrations. Of Spaniards washed up on Irish coasts after storms. Of one German engineer exiled here during the First World War.

A DEEP CONCLUSION

Invasions made every one of us the way we are. They shaped the architecture of our homes and the borders of our fields. Our language, our pronunciation are formed around ancient battle lines. As is the food we eat and the music we make. It’s all there if you care to look, but more importantly, it’s there where you can’t look, deep, deep inside.

So fundamental is this to us, that I suspect the lack of it can make fantasy worldbuilding feel very thin. In other words, every book we write needs to be, at some level, a Book of Invasions.

*Not that again!

I trust the “The Book of Invasions” mentions that the Normans came to Ireland at the request of Dermot MacMurrough, who sought their help to recover his kingdom? From his point of view it was not an invasion but a liberation. But he was neither the first nor the last ruler to discover that when you invite foreign armies into the realm, they have a pesky habit of not going away.

The first version of the book was compiled from earlier sources *before* the Norman invasion. The anonymous scholar was probably long dead before they came over. Mind you, he certainly knew about the Vikings and didn’t include them.

Absolutely! This is the sort of thing we overlook a lot on my side of the pond, seeing as how what came before us is mostly obliterated and had not really been assimilated beyond distinctive place names. Most of us live sadly outside of history.

But our very language itself is practically a roadmap of invasions of your neighboring isle, Peadar — the celtic ‘useless do’ that survived a germanic invasion, the simplified grammar that evolved as the two similar languages of old norse and old english rubbed against each other and dropped their case endings (I thank the vikings everyday that I don’t have to ascribe gender to inanimate objects!), and the influx of french vocabulary (and frenchified norse) in the wake of the norman conquest that infused english even further. Dial it forward a bit, and you have the stuff of cultural ‘invasions,’ further latinate influences during the renaissance and enlightenment.

A writer of other worlds would always do well to study our own.

Thanks, Bill, it’s fascinating stuff. I never knew it was the Vikings that wore away the English case-endings 🙂

I saw an amazing documentary years ago about a tribe in a jungle in Borneo — somewhere like that. They looked a little different from the tribes around them and when their language was analyzed, it was found to contain words from medieval China, and Vietnamese words from a century later than that etc. The linguists were able to trace that group’s whole, centuries-long journey from the loan words they had picked up along the way.