Richard Carpenter and Robin of Sherwood

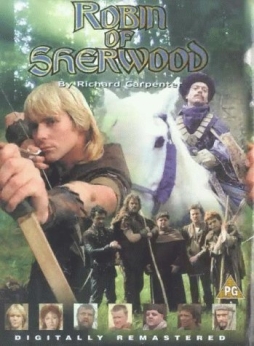

I read some bad news earlier this week: Richard Carpenter died. Carpenter, 78 at the time of his death on February 26, was an actor and television writer. He created several shows; he’s probably best known for his children’s series Catweazle, the animated Dr. Snuggles, and the show that I want to talk about here, the ITV-broadcast series Robin of Sherwood. It’s easily my favourite interpretation of the Robin Hood story, and perhaps my favourite filmed piece of sword-and-sorcery.

I read some bad news earlier this week: Richard Carpenter died. Carpenter, 78 at the time of his death on February 26, was an actor and television writer. He created several shows; he’s probably best known for his children’s series Catweazle, the animated Dr. Snuggles, and the show that I want to talk about here, the ITV-broadcast series Robin of Sherwood. It’s easily my favourite interpretation of the Robin Hood story, and perhaps my favourite filmed piece of sword-and-sorcery.

Robin of Sherwood ran from 1984 to 1986. Carpenter reimagined the story of Robin Hood from top to bottom, infusing it with magic, myth, and the politicised anger of youth. He also created a show that unobtrusively captured the late twelfth century with remarkable fidelity, both in its visual aspects like props and costumes, and also in its social hierarchies and habits of thought. The series ran for three seasons before its production company ran into financial problems. Some plot threads were ended prematurely, without resolution or real development. Carpenter’s observed that the ending as it is works well enough, and I can see his point. Still, I can’t help but wish that the show had gone a bit further.

As it is, Robin of Sherwood’s one of the best examples I can think of in any medium of how to reinterpret a legend. The fact that the re-interpretation was specifically as a fantasy drew me when I first saw it as a teen, but I think the fantasy wouldn’t have mattered if it weren’t for the way Carpenter made the fantasy elements harmonise with themes and elements already present in the Robin Hood tales. Carpenter’s Robin is the spiritual son of Herne the Hunter; Herne’s a god of the ancient and fearsome forest of Sherwood incarnated in a hermit-like shaman. Robin bears a magic sword called Albion, one of the Seven Swords of Wayland. He and his Merry Men (never called that in the show) encounter Templars, Kabbalists, a cursed village populated by ghosts, Satanists, and, in the first episode, an evil wizard. The famous silver arrow is a symbol of Saxon rebellion, a magical item representing freedom.

Not every one of the show’s twenty-two episodes involved explicit magic, but the atmosphere of the show was almost always profoundly magical. In part that comes from the use of elements of neo-pagan lore. The show uses the conceit of the survival of pagan beliefs quite well; one can quibble with the history involved, but dramatically it works.

Not every one of the show’s twenty-two episodes involved explicit magic, but the atmosphere of the show was almost always profoundly magical. In part that comes from the use of elements of neo-pagan lore. The show uses the conceit of the survival of pagan beliefs quite well; one can quibble with the history involved, but dramatically it works.

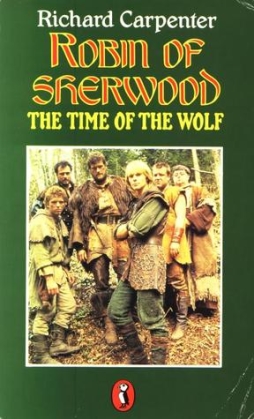

Robin and his Merry Men were all young, seeming to be in their twenties or, in the case of Much the Miller’s Son, even younger. There was a punk energy to their rebellion, a self-conscious anti-authoritarianism. These were the sort of outlaws you thought really would rob from the rich to give to the poor.

The acting in the show was uniformly excellent. There were two Robins in the show’s three years. Michael Praed was the first, Robin of Loxley, a poor man and a rebel’s son, forced into outlawry to save his foster-brother Much. Praed played Robin as an intense, charismatic visionary. It was a compelling lead performance, but he left the show after two seasons, and was replaced by Jason Connery. Connery’s Robin was originally the well-born Robert of Huntingdon; Carpenter was able to use the change of actors to play about with a different interpretation of Robin, going back to versions of the story that had Robin Hood as a dispossessed nobleman.

Judi Trott’s Marion of Leaford was a young noblewoman who escaped a life as a pawn of the church to live with Robin in Sherwood; her high-status background gave her a distinct role among the outlaws, particularly in the first two seasons. Clive Mantle (Lord Greatjon Umber in HBO’s A Game of Thrones) played a Little John rescued by Robin from the control of an evil sorceror after a brutal quarterstaff battle on a narrow log bridge. Phil Rose portrayed a clever, literate Friar Tuck. Peter Llewellyn Williams’ Much the Miller’s Son was what would have been called “simple” at the time in which the show was set, a gentle naïf who made for an interesting contrast with the rest of the cast.

Judi Trott’s Marion of Leaford was a young noblewoman who escaped a life as a pawn of the church to live with Robin in Sherwood; her high-status background gave her a distinct role among the outlaws, particularly in the first two seasons. Clive Mantle (Lord Greatjon Umber in HBO’s A Game of Thrones) played a Little John rescued by Robin from the control of an evil sorceror after a brutal quarterstaff battle on a narrow log bridge. Phil Rose portrayed a clever, literate Friar Tuck. Peter Llewellyn Williams’ Much the Miller’s Son was what would have been called “simple” at the time in which the show was set, a gentle naïf who made for an interesting contrast with the rest of the cast.

Particular notice, I feel, has to go to Ray Winstone’s Will Scarlet. Scarlet’s something of a generic Merry Man in most retellings, not Robin’s best friend like Little John nor the devout man of the cloth like Friar Tuck. Winstone made Scarlet unique and almost terrifying. His character is always angry; scarlet with rage, if you like. Robin meets him in the dungeons of the Sheriff of Nottingham. Scarlet’s name was originally Scathlock. Then three Norman mercenaries raped and killed his wife. Scarlet killed them, and his rage and thirst for violence haven’t left him since.

Even more interesting, though, was an addition to the Robin Hood legend that began with this show. Robin of Sherwood was the first retelling of the legend in something like five hundred years to create a Merry Man. What happened was this: in the first episode, Robin battled an evil sorceror, Simon de Belleme. Belleme had a bodyguard, a Saracen named Nasir, played by Mark Ryan, who was originally planned to fall in battle with Robin. Ryan’s portrayal of Nasir caught Carpenter’s imagination, and he rewrote the script so that Nasir had a change of heart and joined the outlaws in Sherwood.

Even more interesting, though, was an addition to the Robin Hood legend that began with this show. Robin of Sherwood was the first retelling of the legend in something like five hundred years to create a Merry Man. What happened was this: in the first episode, Robin battled an evil sorceror, Simon de Belleme. Belleme had a bodyguard, a Saracen named Nasir, played by Mark Ryan, who was originally planned to fall in battle with Robin. Ryan’s portrayal of Nasir caught Carpenter’s imagination, and he rewrote the script so that Nasir had a change of heart and joined the outlaws in Sherwood.

As far as I can see, every major portrayal of Robin Hood on screen since has had a Saracen Merry Man. You can see why the idea has a certain appeal for multicultural audiences today. The addition of Nasir to the Sherwood gang came about not directly because of a desire for multiculturalism, so far as I know, but because of what multiculturalism gives a creator — new story elements, new spins on old ideas, in this case a new character to become a piece of an old legend. Ryan’s Nasir was a fascinating, fully-rounded figure; not entirely fluent in English, understanding the language better than he spoke it, he was a silent, watchful man, stern and menacing except when he’d suddenly break into a wide smile.

The show was well-directed, with a strong visual sense. Some of the special effects and audio effects are very much of their time, but the photography (shot on location at various castles and woods in Britain) is powerfully effective.

The show was well-directed, with a strong visual sense. Some of the special effects and audio effects are very much of their time, but the photography (shot on location at various castles and woods in Britain) is powerfully effective.

Above all, the costumes and set design create a strong sense of place and time. That’s in keeping with the way the show seemed to make use of the actual social structure of the time; the way the spiteful-yet-cunning Sheriff of Nottingham viewed his serfs as subhuman, for example, or the way Marion and Tuck were more at ease dealing with nobles than any of the lowborn characters. A heated discussion between the Sheriff and his brother, Abbot Hugo, about the ownership of a fish pond seems like it could have come out of an actual historical annal (I mean that in the best way; there’s real drama in such annals, which Carpenter understood). When I first saw the show, and for many years after, the fantastical and magical aspects of it were what struck me most powerfully. Now I see how, in an understated way, it used the reality of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries to find powerful story elements. For a show that was consciously concerned with Englishness, that use of history seemed to fit in naturally.

Any extended discussion of the show would of course be incomplete without mention of the soundtrack. Written and performed by the Irish folk band Clannad, the show has some of the best music of any TV show I’ve ever seen. It’s haunting, memorable, and fits the story perfectly. You can find a fair number of clips on YouTube.

Overall, the show created an inimitable feel, a mix of sword-and-sorcery, historical drama, and Hammer horror (that last most notable in the two-part “The Swords of Wayland,” with its Satan-worshipping nuns in skin masks). Somehow all the pieces and elements came together. The show could go big (as I said: Satan-worshipping nuns in skin masks), and could also focus in on quiet, personal moments. It used realism as a base for fantasy.

Overall, the show created an inimitable feel, a mix of sword-and-sorcery, historical drama, and Hammer horror (that last most notable in the two-part “The Swords of Wayland,” with its Satan-worshipping nuns in skin masks). Somehow all the pieces and elements came together. The show could go big (as I said: Satan-worshipping nuns in skin masks), and could also focus in on quiet, personal moments. It used realism as a base for fantasy.

One of my favourite scenes came in the first episode. Robin, in the midst of a daring escape from the Sheriff’s castle, flees into the bedchamber of Lady Marion; it’s their first encounter. The way the two actors play it, the way it’s written and shot, I find myself aware both that I’m watching two young people meeting each other and feeling a powerful undeniable attraction, and at the same time watching the acting-out of a myth: Robin Hood and Maid Marion meeting and falling in love. For me, it’s a powerful kind of double-vision; a legend given real and specific form. Robin of Sherwood, at its frequent best, managed to hit that difficult target as well as anything I’ve ever seen.

In the words of the show: “Nothing is forgotten. Nothing is ever forgotten.”

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I enjoyed much of Carpenter’s vision for “Robin”, though felt it went off the rails to an extent when Praed left and Connery took over – he just didn’t work for me. It certainly took some interesting directons with the traditions, though left others faithfully alone. And it made Ray Winstone’s career, no doubt of that.

And the one addition he made – Nasir – was a masterful one, and very well (and subtly) played. Interesting how many post-Carpenter renditions of Robin Hood have seemed to take that idea on board (Morgan Freeman in “Prince of Thieves”, and the recent BBC series which went in some very anachronistic directions with its post-Gulf War sensibility).

I haven’t seen this series since it aired, gotta look for it now. And I never realized Winstone was in it!

I thought one of the things the show did really well was its portrayal of the way the Christian church might have been if it had existed in a world where verifiable magic actually worked. Particularly Abbot Hugo’s “let’s just ignore them and hope they go away” attitude toward the pagan celebrations in “Lord of the Trees”. Also Friar Tuck’s in-depth knowledge of demonology and the way he described it as something that everyone at seminary would have been taught; my guess is that wouldn’t have been the case in real life, but in a world where you might wind up with Satan-worshipping nuns in your basement, it makes sense to make it part of the core curriculum.

I just want to comment on the Series.