Atomic Fury: The Original Godzilla on Criterion Collection Blu-ray

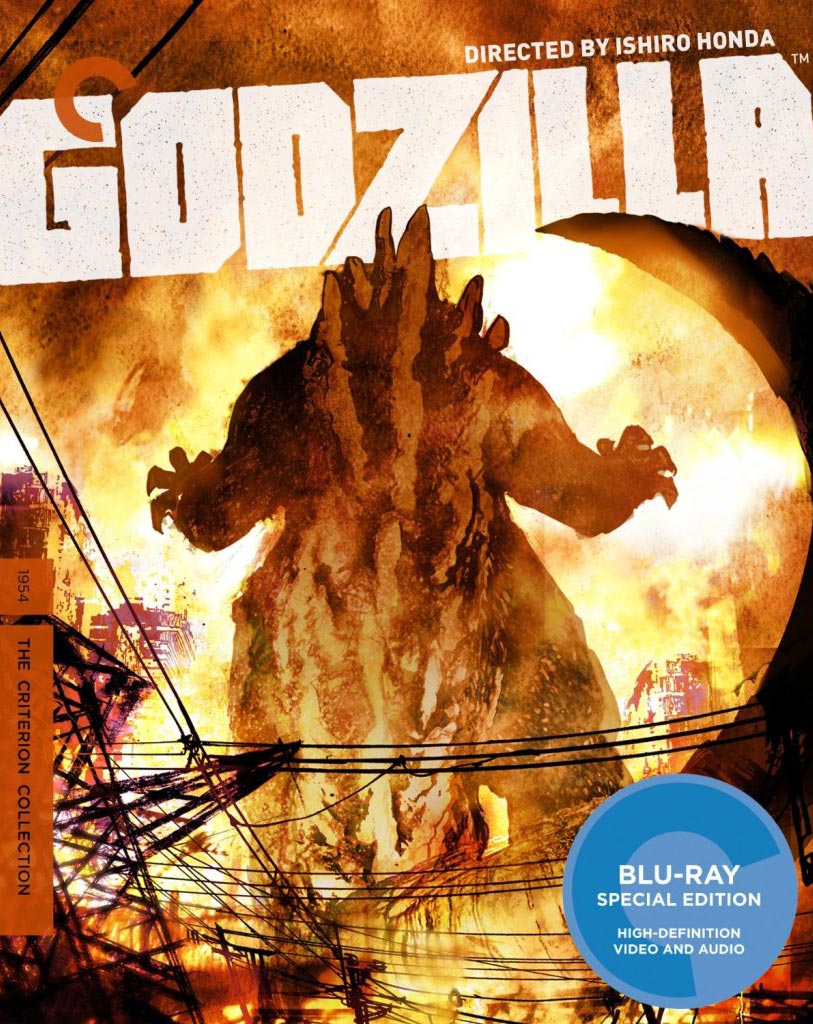

This week’s release of the original 1954 Japanese Godzilla (Gojira) on Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection is a major step in recognition for the film in the US. Yes, that’s the Criterion Collection, the premiere quality home video release company, acknowledging that Godzilla is a world cinema classic.

As a life-long Godzilla and giant monster fanatic, I can tell you what a long journey we’ve taken to get to this point. When I became feverishly interested in Japanese fantasy cinema, beyond the boyhood love, in my early twenties, Godzilla and its brethren had almost zero respect in North America. And zero quality home video releases. Even as the awful Roland Emmerich Godzilla hit screens to howls of hatred, there was no corresponding move to get the real films out to North American viewers in editions with subtitles and decent widescreen presentations.

In the mid-2000s, the shift started. The original Godzilla, not the Americanized version with Raymond Burr, got a theatrical stateside release, and then a DVD from Classic Media. G-Fans such as myself were finally freed from having to see the movie on bootleg VHS tapes and could recommend it easily to friends, promising them that the Japanese original would blow their mind with its quality. Now, we’re getting into the big-time cineaste world with Hi-Def and the Criterion Collection.

However, I’d like to temper my enthusiasm for 1954’s Godzilla with this statement: although a great film, it is not my favorite Godzilla movie, nor is it representative of the series.

The Japanese science-fiction films that boomed in the late ‘50s because of the success of Godzilla at first followed the U.S. “atomic horror” formula: a semi-documentary style, focus on scientists and the military working to stop the threat, messages about the abuse of radioactive energy/science. Godzilla follows the U.S. model of films like The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and Them!, although infuses its story with Japanese concerns — this is, after all, the only country in history to suffer from an atomic attack. It wasn’t until 1960 and Mothra that the Japanese fantasy film broke away from its Western counterparts and developed a unique identity. The Godzilla films from this era, particularly the wonderful Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964) are the films that gave us Godzilla as a personality, whether as destructor or superhero. Mothra vs. Godzilla (released theatrically in the U.S. as Godzilla vs. The Thing and later given the video title of Godzilla vs. Mothra) is my pick for the best movie in the series, mixing some of the seriousness of the original Godzilla with the new colorful Japanese style. The films of the 1960s are much more “fun” and re-watchable than the 1954 film, which is, frankly, an extreme downer.

But what a brilliant downer! Godzilla ’54 is the finest of the atomic monster films of its decade, made with ingenuity and sincerity rarely seen in the American movies of this same genre and period. The creative personnel filled the movie with Japan’s own deep fear of the A-Bomb and the way it affected their society. No other nation could have produced a story of the dangers of the atomic era better than Japan, the first country to feel the devastating effects of that power. Godzilla is a gut-wrenching film because viewers feel the terrors of a whole country made real, visualized with special effects that sear the brain with images of an unstoppable horror.

Godzilla began life as a co-production between the Japanese studio Toho and Indonesia. The planned war film In the Shadow of Honor collapsed, however, when the Indonesia investors backed out. Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka faced a dilemma: half a budget and no film. He needed something new to pitch to executive producer Iwao Mori at Toho.

On the flight back to Tokyo, or so the legend goes, Tanaka had his brainstorm: make a film about an atomic monster rampaging through Japan. A combination of forces pushed Tanaka toward this idea. One was the recent “Lucky Dragon #5 Incident.” A Japanese fishing boat was caught in the radiation blast from the U.S. atomic test on Bikini Atoll. The fisherman returned to port, dying from radiation sickness, and some of the contaminated tuna made it to market. The Japanese press ran with the story, and it incensed the public at what was touted as “The Second American Bombing of Japan.” Hyperbole aside, the fate of The Lucky Dragon #5 drew attention back to the nuclear issues that the Japanese government tried to keep away from the public in the immediate post-war years. After almost a decade of silence, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were major topics again and at the forefront of policymaking.

But there was a basic financial trigger to Tanaka’s choice to have a big monster batter around Tokyo’s buildings: the recent box-office success in Japan of King Kong (never shown in the country until 1952) and The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. Tanaka pitched Godzilla as Toho’s take on the latter. It seems Tanaka wanted to incorporate elements of King Kong into the movie as well, since he originally suggested a monster that was a sort of “aquatic gorilla.” Thus, the monster’s Japanese name: “Gojira,” a portmanteau of the words gorira (“gorilla”) and kujira (“whale”).

(Rumor has long held that the name “Gojira” came from a nickname for an immensely fat man in Toho’s publicity department — or maybe he was a stagehand. The more years pass, the more it seems this was invented after the character’s success. Director Ishiro Honda’s widow said her husband and Tanaka deliberated over the name, and that tall tales were common among Toho’s backstage boys.)

Many talented people contributed to Godzilla’s success, but unless I plan to write a volume as thick as a Robert Jordan novel, I have to telescope this overview down to the two men who are the big stars of the movie: director Ishiro Honda and visual effects supervisor Eiji Tsubaraya. The two men represent the human and monster side of the story.

Ishiro Honda (1911–1993) is Japan’s greatest science-fiction and fantasy director, but he only started to receive his due as an artist in the years after his death. Originally an assistant director for Akira Kurosawa — with whom he remained a close friend and collaborator until his death — Honda directed his first film in 1951, a drama about pearl divers. His 1953 war film Eagle of the Pacific, with visual effects by Tsubaraya, was a big hit, and landed Honda the job to direct Gojira when Tomoyuki Tanaka’s original choice was unavailable. Producer Tanaka could not have selected a better director. Honda served in the military during World War II and visited the site of Hiroshima not long after its devastation. It was a pivotal moment in his life, and it forever haunted him. In Honda’s own words:

Most of the visual images I got were from my war experience. After the war, all of Japan, as well as Tokyo, was left in ashes. The atomic bomb had emerged and completely destroyed Hiroshima … If Godzilla had been a big ancient dinosaur or some other animal, he would have been killed by just one cannonball. But if he were equal to an atomic bomb, we wouldn’t know what to do. So, I took the characteristics of an atomic bomb and applied them to Godzilla.

Honda tackled the film with the conviction — admirable if a bit naive — that it might bring an end to nuclear testing. His treatment of the central character of Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), a scientist wounded in World War II who has perfected a device that might kill Godzilla, is central to his anti-nuclear message. Dr. Serizawa fears that his new invention, “the oxygen destroyer,” could turn out to be an even worse weapon than the H-bomb, and initially refuses to use it on Godzilla because he fears its long-term consequences in government hands. Honda invests tremendous power into the scene where Serizawa’s fiancée Emiko (Momoko Kochi) and her new love Ogata (Akira Takarada) confront Serizawa in his lab about saving Tokyo from the monster. What is at stake between these three characters, now in the wake of the worst disaster to fall Tokyo since the fire-bombing, is enormous, and Honda’s handling of the scene makes it a crucible of tension. Dr. Serizawa lays out to Ogata exactly why he refuses to release the oxygen destroyer against Godzilla:

Ogata, if the Oxygen Destroyer is used even once, the politicians of the world won’t stand idly by. They’ll inevitably turn it into a weapon. A-bombs against A-bombs. H-bombs against H-bombs … As a scientist — no, as a human being — adding another terrifying weapon to humanity’s arsenal is something I cannot allow.

Of course, Serizawa ultimately gives in — a requiem over the radio sung by Japanese school children praying for peace makes him realize he has a responsibility to act. But Serizawa makes a sacrifice to ensure that his weapon will never be used again. The tragedy of Dr. Serizawa is the film’s best dramatic through line, and — after the imagery of Godzilla itself — what leaves the greatest impression on viewers.

Honda always paid attention to the human aspects of his fantasy films, even if the script and spectacle almost overwhelmed them. But with Godzilla he had a great amount of personal drama to work with, and did amazing things with the many “quiet” moments in the film. Close friends of Honda have often commented that the director wanted more than anything to make films similar to those of Yasujiro Ozu, a famous director of small-scale dramas. I see this leaning strongest in Godzilla, where Honda can make a moment as simple as Emiko kneeling down to take off her shoes after she has returned from Serizawa’s lab into something that can wring tears from an audience. The moments inside the house of Emiko’s father, Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura, who starred in The Seven Samurai the same year) right before Godzilla’s attacks are filled with silent, unbearable tension.

One scene in particular (cut from the U.S. version) that astonishes me for what Honda is able to say in it occurs on a commuter train. Three passengers, who appear nowhere else in the film, discuss the newspaper headlines about Godzilla possibly making landfall. Honda captures the essence of post-war Japanese lifes with the short scene:

Female Passenger: This is awful. Atomic tuna, radioactive fallout, and now this Godzilla to top it off! What if it shows up in Tokyo Bay?

Male Passenger #1: It will probably go straight for you first.

Female Passenger: You’re horrible! [pause] I barely escaped the atomic bomb in Nagasaki — and now this!

Male Passenger #2: I’ll have to find a place to evacuate to.

Female Passenger: Find me one too.

Male Passenger #1: Evacuate again? I’ve had enough.

The conversation is so … resigned. The last line is spoken with a sense of futility and surrender. These people lived through World War II, and now can only shrug that their nightmare is not over. (Notice the reference to the Lucky Dragon #5 regarding atomic tuna.)

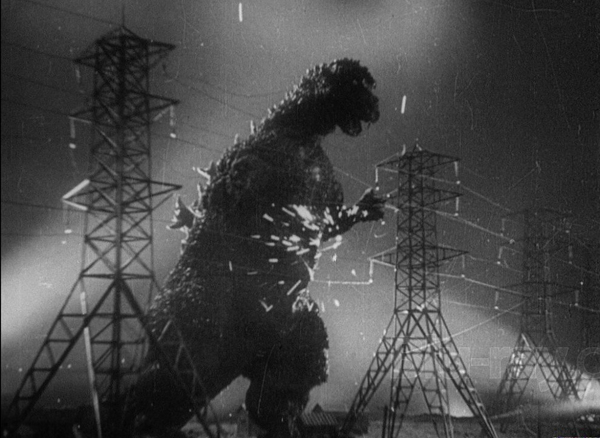

Honda’s direction gives Godzilla its human quality. But effects genius Eiji Tsubaraya gives us its star, the fifty-meter-tall radioactive beast that transformed into one of cinema’s greatest icons. Tsubaraya also produced the stunning images of destruction, a Tokyo turned into a sea of flames, that haunt viewers. Honda brings us the story and the people; Tsubaraya brings us the terror and fury.

Eiji Tsubaraya (1901–1970) is one of VFX’s great superheroes, along with Willis O’Brien and Ray Harryhausen. He originally did special effects for Toho’s many war pictures. Because Japan no longer had a military, it was up to Tsubaraya to create miniature tanks and planes to stage the battle scenes. He was already talented with models, but he had never handled anything of the scope of Godzilla, and crafting the large monster suit for stuntman Haruo Nakajima was a trial-and-error task.

Tsubaraya’s effects in Godzilla aren’t strictly “realistic.” But they are almost all completely “effective.” There are a few spots where the models look a bit wonky (a scene of a helicopter falling over in a wind storm isn’t one of the finer moments), but the creativity and size of the work is breathtaking. Viewers who dismiss “suitmation” as cheap should take a close look at the scenes of destruction in Godzilla: an immense amount of time and effort went into detailing the miniatures, lighting the sets, rigging explosions, and choreographing all the elements together. This was an enormous project, and nobody at Toho Studios had seen anything like it before.

Godzilla’s first appearance, breaching over a ridge on Odo Island while villagers and reporters turn to flee down a path, is a stunning entrance and one of the great moments in monster movie history. Earlier scenes of destruction that leave the monster unseen — boats wrecked from beneath, island huts smashed apart — create the sense of a creature of unimaginable power. The revealed beast does not disappoint.

Godzilla has two urban destruction sequences. The first has him briefly come ashore and derail a train. The second is the film’s centerpiece: a long rampage through Tokyo that turns the middle of the city into ashes. Tsubaraya pulls out every trick — including a brief moment of stop-motion animation — to make this a steam-roller of a scene. Some clever opticals mix humans seamlessly with the monster, such as a close-up of people fleeing along a street as Godzilla’s feet crash onto the foreground. The music from Akira Ifukube adds a funeral dirge feeling as Godzilla makes the skyline of Tokyo into a wall of fire; some of the most upsetting images in the movie are Tsubaraya’s compositions of the burning city against the night sky, with the spiky shadow of the monster moving slowly across it.

Later Godzilla films shy away from showing the human toll of these monster rampages; they were more science-fiction adventure stories than horror tales. But Tsubaraya shows citizens dying from radioactive fire in masses, buildings collapsing on people, and a crying woman holding her children and telling them they will soon be joining their father right before Godzilla brings down a wall on them. This is VFX as an art form, delivering not only spectacle, but grueling emotional impact. The first time I saw the Japanese version of Godzilla in a theater in the US, no one laughed at a single effect, nobody giggled at any of the model work. The packed theater sat in stunned silence watching a city die. This is the reaction Tsubaraya wanted, and he got it — even fifty years later.

Not long after the grimness of Godzilla, Tsubaraya got to unleash his inner child and have crazy fun with movies like Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster and his superhero television show Ultraman. We got the best of both worlds from the man.

Godzilla ’54 concludes with a message directed straight at the controversy of nuclear testing. Dr. Yamane (in a line cut from the U.S. version) ponders Godzilla’s apparent destruction: “I can’t believe that Godzilla was the last of its species. If nuclear testing continues, then someday, somewhere in the world … another Godzilla may appear.”

The line has important metaphoric resonance, especially for director Honda and his hope that nuclear testing might end. “Another Godzilla” is the threat of another great nuclear horror that humanity may unleash on itself — and not survive. But Dr. Yamane’s prediction ended up a literal truth as well: Sequels! Many of them! A glorious franchise flying from the thrills of Mothra vs. Godzilla and Destroy All Monsters; to oddball head-trips like Godzilla vs. Hedorah (a.k.a. Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster); to low-rent junk like Godzilla vs. Megalon and Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla.

Godzilla became a sensation and a star through the global success of the movie — but not in its original form. It was the Americanized version, 1956’s Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, that proliferated across the world. This version, which was overseen by director and editor Terry Morse, re-worked the Japanese film with new footage of actor Raymond Burr (on the cusp of fame with Perry Mason) to create something accessible for 1950s U.S. audiences. It was this version that spread to theaters across North America and Europe, and because of its importance to Godzilla’s history, the Criterion Collection includes it on the new Blu-ray as a bonus feature.

Godzilla, King of the Monsters! is absolutely worth watching as a follow-up to Godzilla. Those of us who grew up on Godzilla films on TV have strong memories of watching Raymond Burr comment on the monster’s destruction with Murrow-like gravitas. But it isn’t merely nostalgia that makes Godzilla, King of the Monsters! worth re-visiting after watching the uncut Japanese version. The US creative team did an excellent job with the re-cut, and although the result lacks the power of the original, it is respectful of the movie and maintains its grim tone. The characterizations of the Japanese cast suffer the most, since the principals have less screen time in order to accommodate Raymond Burr’s scenes. But Eiji Tsubaraya’s effects remain intact and have the same wrenching quality.

Plus, it’s educational to watch how Terry Morse and his team worked with the Japanese footage to create the U.S. version. There’s some clever “work-around” solutions, and a few that don’t quite make it. (Where did they get that double for the back of Dr. Yamane’s head?) Raymond Burr treats the assignment with the same seriousness as any role he took, and he adds great authority to the US side of the film.

The transfer on the Criterion Collection Blu-ray is great, but that’s no surprise. The Criterion Collection has made a name for itself because of its quality transfers that keep the film true to its source. The print shows some minor damage such as white flecks, but nothing distracting, and a heavy digital clean-up would have erased the natural film grain. Godzilla has certainly never looked this good since its premiere in Tokyo in 1954.

I will close with the words of director Honda in the 1980s, where he explains why Godzilla remains powerful so many years after it first stomped into movie theaters:

It is sad that the number of atomic bombs hasn’t been reduced by one since [1954]. We’d really like to demand abolition of nuclear weapons to both America and Russia. That is where Godzilla’s origin is. No matter how many Godzilla movies are produced, it is never enough to explain the theme of Godzilla.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Great write-up for a fantastic movie. While my heart is with the lighter, more anti-heroic Godzilla of the 60s and 70s, the original film is in a class by itself and it’s largely because of the knowledge that scenes like the radiation-burnt people clogging the hospitals weren’t mere fantasy but fresh memory for the Japanese at the time.

Too bad that was lost on Roger Ebert, who went out of his way to mock the film when the restored version was screened in the U.S. a few years back.

Ebert hates Godzilla because Godzilla has a more slender waistline than him.

[…] Black Gate (Ryan Harvey) on Atomic Fury: The Original Godzilla on Criterion Collection Blu-ray. […]

[…] before but doesn’t mind that it can’t. Showing reverence to the underwater finale of the 1956 Godzilla, Guillermo del Toro stages a sequence around the rift in the Pacific floor that pays off […]

[…] not have noticed it, because I’ve only had a few opportunities to discuss it at Black Gate (here and here), but Godzilla is sort of a huge big damn bloody deal to […]

[…] already written extensively on Godzilla’s origin tale in my review of the Blu-ray of the original. Here is the “on-the-go” […]