Mark Rigney Reviews Ivy’s Ever After

Ivy’s Ever After

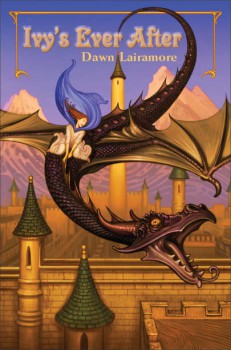

Ivy’s Ever After

Dawn Lairamore

Holiday House, Inc., (311 pp, $16.95, 2010)

Reviewed by Mark Rigney

There is a land where children go, to fill their minds with castles and kings and queens and rescues and, well, you know. All that stuff. For some, that land comes equipped with polyhedron dice. For seasoned readers ready to dispense with their dice, one can always fall back on Tolkien, Sir Walter Scott, or Le Morte d’Arthur. But what if you happen to be, say, nine years old, and a veteran of second-hand My Pretty Ponies and half-remembered episodes of TV’s greatest fantasia, Sesame Street? The Babysitter’s Club won’t be for you, no, and Swallows and Amazons might be a little dated. Time, then, to sample the gentle charms of Ivy’s Ever After.

Dawn Lairamore has two things on her mind from the get-go. First, she sets out to tell a quite traditional tale set (of course) in a distant, unknown realm where a crisis of succession will soon vault young Princess Ivy into being the only one in the entire kingdom who can save the kingdom entire. Second, she wants to upend the genre just enough to ensure that Ivy actually will be a heroine worthy of a post-Sigourney Weaver world, a heroine who will rely not at all on the hapless men in her life (including her father, the king), and, indeed, not by any male aside from the rather large, winged exception of the dragon set to guard Ivy’s tower.

You see, Ivy has to let herself get locked into Ardendale’s special treaty-determined tower on her fourteenth birthday in order for a prince to slay the dragon that guards the door, rescue her, marry, and keep the country both laden with heirs and free from marauding dragons. (The treaty must be upheld, at all costs.) But of course Ivy, being both plucky and smart (not to mention adolescent), has no desire to hole up in a tower, and worse – or so thinks her nurse – she has taken a rampant dislike to the Prince, a dastard named Romil who couldn’t be any more evil if it were imprinted with ink on his eyeballs. Of course nobody else seems to notice, but then, they are not adolescent, plucky or smart, like Ivy.

The truth is, this concoction works disarmingly well, and suffers far more from my summation than it does in the hand. Ivy’s Ever After swims along with a gliding pace, a useful cliffhanger or two, and a pair of spirited servant-girl friends. Ivy, you see, is not only a model for empowering young female readers, she also demonstrates an admirable willingness to ignore class and social boundaries. She is, in the end, an idealized Democrat, a girl not bound so much by the world of faerie and legend (where responsibility and loyalty would surely trump even Kim Possible) but to our own modern time of equality for all – at least on paper. The equality, that is. Just how many people, gentle reader, do you socialize with who are not within the bounds your own economic class?

The dragon doesn’t arrive until (like clockwork) the second third of the narrative, but this delay is handled skillfully. Ivy dreads the tower, and the dragon, and Prince Romil; her despair, anger, and various attempts to foil fate are the engine that keep us reading, and happily so, right up to the moment Ivy steps into the tower’s sturdy walls. And of course the dragon, Elridge, has an agenda and a personality of his own, one that echoes somewhat oral storyteller Jay O’Callahan’s The Little Dragon. O’Callahan’s scaly hero, just like amiable Elridge, isn’t much of a fire-breather, and is picked on for it.

Several other beasties crop up, including the requisite trolls and massive spiders, here re-named cave crawlers. On the plus side, the troll chief isn’t just a chief, he is a guamp, and he sits resplendent on his boulder throne in a truly revolting headdress made of cave crawler; imagine Russian winter fashion, circa 1800, but enlarged enormously, and with spider’s legs encircling the wearer’s cheeks.

The odds are great, the tasks many. That Ivy will persevere is never in doubt – this is middle-grade fiction, after all, not The Blair Dragon Project – but it remains one of the basic and resurgent pleasures of fiction to root for a determined heroine. If the narrative seems tidy to a fault, and if the many leave-takings post-climax lack punch, the book as a whole is clear, well-spun, and never talks down to its readership. Best of all, it throws in regular doses of good humor and sly asides as if perhaps Lairamore’s next outing might contain a shade less Blyton and a touch more Austen. The land of faerie ever-after wouldn’t mind at all.

__________

A slightly different version of this review originally appeared in Black Gate Magazine #15

Mark Rigney is the author of the play Acts of God (Playscripts, Inc., 2008) and the non-fiction book Deaf Side Story: Deaf Sharks, Hearing Jets and a Classic American Musical (Gallaudet University Press, 2003). His short fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and appears in The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review, Talebones, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, among many others, and an upcoming trilogy in Black Gate. His website, with links to many of his original stories, stage plays and the dreaded Anti-Blog, is www.markrigney.net.