Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars, Part 2: The Gods of Mars

I played a bit rough with A Princess of Mars last week in my first installment of this eleven part mega-series on the Martian novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs. That book knocked me out when I first read it as a junior high school kid, but it was also the first ERB book I ever picked up. Now that I’ve read most of Burroughs’s canon, the flaws of his first book seem more obvious. For all that is wonderful about A Princess of Mars, it looks like a runt compared to the book I knew was snapping at its heels: The Gods of Mars. Also known as: “Edgar Rice Burroughs gets the knack.”

I played a bit rough with A Princess of Mars last week in my first installment of this eleven part mega-series on the Martian novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs. That book knocked me out when I first read it as a junior high school kid, but it was also the first ERB book I ever picked up. Now that I’ve read most of Burroughs’s canon, the flaws of his first book seem more obvious. For all that is wonderful about A Princess of Mars, it looks like a runt compared to the book I knew was snapping at its heels: The Gods of Mars. Also known as: “Edgar Rice Burroughs gets the knack.”

Our Saga: The adventures of Earthman John Carter, his progeny, and sundry other visitors and natives, on the planet Mars. A dry and slowly dying world, the planet known to its inhabitants as “Barsoom” contains four different human civilizations, one non-human one, a scattering of science among swashbuckling, and a plethora of religions, mystery cities, and strange beasts. The series spans 1912 to 1964 with eleven books: nine novels, a book of linked novellas, and a volume collecting two unrelated novellas.

Today’s Installment: The Gods of Mars (1913)

Previous Installment: A Princess of Mars (1912)

The Backstory

In his original proposal to editor Thomas Newell Metcalf at Munsey’s Magazines regarding a novel of Martian adventure, Edgar Rice Burroughs suggested he could write three books from the concept. But he apparently wasn’t certain about the content of the second and third volumes to follow A Princess of Mars, since it was Metcalf who gave him the idea of where to start the next book. After Metcalf rejected Burroughs’s second novel, The Outlaw of Torn, he urged the author to return to Mars and send John Carter into the Valley of Dor, the mysterious paradise mentioned a number of times in the first book. Burroughs ran with the concept, and finished the novel in the beginning of October 1912.

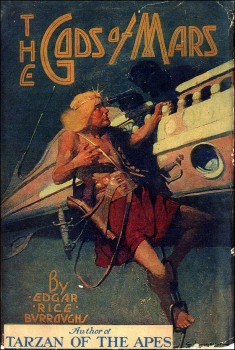

The serialized version appeared in All-Story in January-May 1913 and was an even greater success than A Princess of Mars. It helped that Burroughs’s fame had skyrocketed from the popularity of something called Tarzan of the Apes published in October 1912, and his name on the cover of a magazine was a money-printing press. A. C. McClurg published the first hardback of The Gods of Mars in 1918.

By the way, I own a 1924 hardback edition from Grossett & Dunlap. The dust jacket is in horrendous shape, but it’s still a prize among my collectible classics and the oldest copy of any Burroughs book in my extensive library of his work. Re-reading the novel for this review, I read primarily from this edition, which gave the book an extra pulp punch.

The Story

In the prologue, the fictional version of Edgar Rice Burroughs visits John Carter’s tomb and recalls his uncle’s previous adventures on Mars (for the benefit of those who came in late). But then he receives a summons to meet with the man supposedly entombed there. John Carter, looking no older than when ERB last saw him, delivers a manuscript about the remainder of his Martian odyssey before vanishing into his “tomb,” never to be seen on Earth again.

The manuscript opens in 1886, twenty years after John Carter first traveled to the Red Planet, and ten after his forced return. While dreaming of Mars and raising his hands to the red spot in the night sky, Carter teleported (?) to the planet once more … although he ends up in a dangerous part of it.

The story proper can be divided in three “acts.” Act I takes place in the Valley of Dor, the supposed paradise of Mars that its inhabitants seek at the end of their lives. When John Carter materalized there, he finds it is anything but a paradise. The valley is a nightmare of murderous plant men, white apes, and the tyrants known as the therns, white-skinned men who rule the valley and eat the flesh of the pilgrims who follow the lie that the valley is Heaven. The greatest among them, the Holy Therns, perpetuate the false promise of the valley. Carter vows to escape and bring the truth of the horrors of the Valley of Dor to the rest of the planet — even if other Martians try to kill him for blasphemy.

The story proper can be divided in three “acts.” Act I takes place in the Valley of Dor, the supposed paradise of Mars that its inhabitants seek at the end of their lives. When John Carter materalized there, he finds it is anything but a paradise. The valley is a nightmare of murderous plant men, white apes, and the tyrants known as the therns, white-skinned men who rule the valley and eat the flesh of the pilgrims who follow the lie that the valley is Heaven. The greatest among them, the Holy Therns, perpetuate the false promise of the valley. Carter vows to escape and bring the truth of the horrors of the Valley of Dor to the rest of the planet — even if other Martians try to kill him for blasphemy.

Carter finds his old ally, the green Martian Tars Tarkas, searching the valley for him. The two fight together against the grotesques of the valley and rescue a red Martian woman, Thuvia, from the prisons of the Holy Therns.

In Act II, John Carter is a prisoner aboard a pirate vessels of the First Born, the black Martians who are at war with the Therns. As the therns dupe the rest of Mars with their religion, so do the First Born dupe the therns with theirs. The pirates take Carter and Phaidor, the beautiful and cruel daughter of the Leader of the Holy Therns, to the underground Ocean of Omean. There rules Issus, a shriveled crone who pretends to be a beautiful goddess. Issus condemns John Carter to a prison isle, along with Xodar, a black warrior John Carter defeated and humiliated. Among the other red Martian prisoners, Carter finds a brave young warrior with incredible physical prowess much like his own, and discovers the boy is his son, Carthoris.

Act III covers John Carter returning to the more familiar wastelands of Mars to expose the Valley of Dor and the goddess Issus. This leads to a massive invasion force heading to attack the First Born and John Carter in a battle to save Dejah Thoris from the clutches of the wicked false goddess.

And then… nope, you don’t get to find out! The book concludes with cliffhanger that must have driven readers crazy in 1913. Fortunately, in 2012 we can just pick up the next book, The Warlord of Mars, and drive onward.

The Positives

I’ve read all the Barsoom saga before, but a few of the later volumes I haven’t returned to in years. Because I’m writing this series as I read through the books in publication order, it is difficult to make overall statements of where a single book stands in the scale of quality. I can use some blurry memories for judgments, but I’m not yet comfortable making any definite statements about a “best” or “worst” installment in the series. That will have to wait until Part 11, when I close the cover on John Carter of Mars.

That said, if I don’t declare The Gods of Mars the best book in the series in the final wrap-up for these reviews, I for one will be extremely surprised. The Gods of Mars is Edgar Rice Burroughs at his most imaginative and exciting. It is a quintessential work of pulp, a textbook definition of the style of the story magazines, and has the bonus of satire and weird subtexts that are astonishing for the time. This is great stuff.

I plan to do a blog-through of Tarzan of the Apes later this year, tackling two chapters per post to get to grips with a complex work. While reading The Gods of Mars I realized I could easily have given it the same treatment; there is so much going on here that is begging for discussion that I need to force restraint on myself to prevent this review from turning into something as long as The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

The first chapter shows how much Burroughs evolved as a writer over only a year: the Valley of Dor comes to life in vivid prose, and the description of John Carter’s first encounter with a plant man as it walks past his hiding place is filled with sickening details that vault off the page and engage all the senses. When the action starts, the tension and rhythm are superior to anything that happened in A Princess of Mars. On every level, Burroughs displays a new confidence as a storyteller and stylist.

And he keeps it up through the rest of the book. Right at the quarter mark, where it feels as if the story will have to run out of energy because of the frantic pace, the Black Pirates of Barsoom sweep down and ignite a battle with the therns. Bam! The action goes up another notch, and a fresh conflict appears within an already intricate situation. Adventure storytelling at its best. And it never flags. New ideas come at a steady pace, so that every few chapters the stakes increase, and new characters and dangers pull the reader deeper into the story. There is no better example of the phrase “never a dull moment.”

And he keeps it up through the rest of the book. Right at the quarter mark, where it feels as if the story will have to run out of energy because of the frantic pace, the Black Pirates of Barsoom sweep down and ignite a battle with the therns. Bam! The action goes up another notch, and a fresh conflict appears within an already intricate situation. Adventure storytelling at its best. And it never flags. New ideas come at a steady pace, so that every few chapters the stakes increase, and new characters and dangers pull the reader deeper into the story. There is no better example of the phrase “never a dull moment.”

The finale doesn’t let down reader expectations, with a four-way epic sky war between two different factions of red Martians, the therns, and the First Born, with the green Martians taking up a ground offensive. In comparison, the action in A Princess of Mars feels, well, kind of puny.

Burroughs avoids repeating himself with the setting. Instead of the desert wastelands of the previous book, the story pulls a major switch and occurs in the phantasmagoria of the Valley of Dor and then the underworld of the Ocean of Omean. These new locations fit with the Barsoomian whole, but give the action imaginative new avenues. The Gods of Mars is the perfect way to do a sequel: up the ante of the first, enhance its mythology, offer enough differences without wrecking the formula. This is exactly how a follow-up to A Princess of Mars should have gone, and it is amazing that we got it.

Critics who dismiss Burroughs as a teller of simplistic, juvenile adventure stories miss how layered he could be. A Princess of Mars is a straightforward tale, but in The Gods of Mars Burroughs begins to show a talent for weaving subtext and satire into the action. Religion is one of the main themes of the novel, and ERB’s view of it — at least here — is far from a favorable one, to put it mildly. He includes not one, but two fake cults that are oppressing the planet with their lies, and sets up his heroes as people willing to risk everything to destroy the “Gods” of the title.

Burroughs pulls no punches, putting some startling statements in the mouths of the characters: “[Y]ou have seen today with what pitiful futility man yearns toward a material hereafter,” John Carter tells Tar Tarkas. “There is no hope, there is no hope; the dead return not, the dead return not; nor is there any resurrection,” shouts a priest of Issus. The biggest moment comes from the warrior Xodar as he ponders that the goddess Issus is not a deity, but only an aged cannibal:

The whole fabric of our religion is based on superstitious belief in lies that have been foisted upon us for ages by those directly above us, to whose personal profit and aggrandizement it was to have us continue to believe as they wished us to believe.

There’s plenty more where that came from, but I don’t want to suggest that Burroughs does nothing but harp on superstition and religion as “opiates of the masses” the whole time. (Oh, Burroughs might come back from the dead and pound me for bringing a Karl Marx paraphrase in as a comparison! Plus, ERB doesn’t portray religion as an “opiate” here: it is a means to get the masses served as a main course at a cannibal feast.) The Gods of Mars isn’t a tract or a nonfiction book, and this use of religion comes in the service of crafting a grand adventure tale; it never threatens to derail the momentum of the story with dull anti-sermonizing. The horrors of the Valley of Dor and the cruelty of the Holy Therns give John Carter a larger goal, one that expands beyond simply rescuing Dejah Thoris, the drive of the previous book. A Princess of Mars only introduced a total Martian threat in its penultimate chapter; The Gods of Mars has one laid out in Chapter IV, and John Carter and his companions are ready to fight to save the planet from the tyranny of the therns, to which they later add the tyranny of Issus:

Our own mortal senses will not be offended if we succeed, for we know that the fabled life of love and peace in the blessed Valley of Dor is a rank and wicked deception. We know that the valley is not sacred; we know that the Holy Therns are not holy; that they are a race of cruel and heartless mortals, knowing no more of the real life to come than we do.

Not only is it our right to bend every effort to escape — it is a solemn duty which we should not shirk even though we knew that we should be revile and tortured by our own people when we returned to them.

After a novel where almost half the length was spent on set-up, this is a huge change: The Gods of Mars opens on action, and then grabs the reader with huge stakes for its hero and its world.

(If you wish to read an academic look into ERB’s use of religion in his fiction, as well as his personal views, I recommend this detailed article from Dr. Robert B. Zeuschner.)

Parallel to the religious satire is the positive theme about the cooperation of races. More of Mars’s biologic history is revealed. The planet originally had three human races of different colors: white, black, and yellow. (The yellow men have not shown up in the series yet, but they’re on the way.) Out of the intermingling of the three arose the red Martians, who became the strongest race. Yes, the story views the mixing of races as a beneficial development — something uncommon in 1913.

Parallel to the religious satire is the positive theme about the cooperation of races. More of Mars’s biologic history is revealed. The planet originally had three human races of different colors: white, black, and yellow. (The yellow men have not shown up in the series yet, but they’re on the way.) Out of the intermingling of the three arose the red Martians, who became the strongest race. Yes, the story views the mixing of races as a beneficial development — something uncommon in 1913.

The racial harmony theme is made explicit during the last third of the book, when John Carter’s assembled party of heroes is fleeing from the Warhoons and racing to get to Helium. This group consists of a white Earthman (Carter), a male green Martian (Tars Tarkas), a female red Martian (Thuvia), a male black Martian (Xodar), and a biracial male from a marriage of a white Earthman and a red Martian woman (Carthoris). “In that little party there was no one who would desert another;” John Carter said, “yet we were of different countries, different colors, different races, different religions — and one of us was of a different world.”

The therns are intriguing for pulp villains: a race of white-skinned murderers who wear blond wigs to recall a time when they were even more “beautiful.” No positive thern character appears in the book; they are thoroughly despicable. Carter has a greater admiration for the black First Born, whom he repeatedly calls “beautiful” and “handsome,” and Xodar becomes his closest ally in the story, even more so than Tar Tarkas. There’s an entire book to be written about the strange nature of race in this novel, which veers between standard pulp stereotypes and the flat-out subversive. How much of this did Burroughs intend, aside from making clear the theme of racial cooperation, and how much of it arose naturally from how he constructed Barsoom? I don’t know, and I’ve mentioned before that ERB is a tricky man to understand; perhaps it’s better to avoid going to deep looking into what an author “intended” and instead stick with what I took away from his words.

The supporting cast is great. Dejah Thoris only appears in a single chapter, and the two female leads who step in, Thuvia and Phaidor, are fantastic. Phaidor is the most memorable new character, a mixture of naivety and femme fatale who expresses the villainy of the therns and their arrogance. Carthoris and Xodar are both excellent as secondary heroes, with Carthoris adding to Carter’s own drama and Xodar giving depth to the First Born.

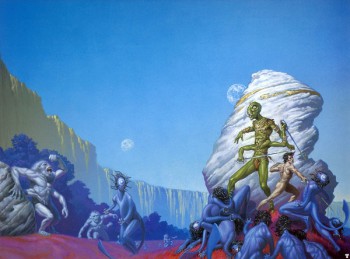

Although this has nothing to do with Burroughs’s writing, the Michael Whelan cover (the one with the blue background two pictures above) for this book is one of my favorite illustrations ever for any ERB novel. Perfect plant men!

The Negatives

The problems of The Gods of Mars are the standard problems of most ERB books: simple chase mechanics, some clunky language, outlandish plot coincidences. Readers who don’t like Edgar Rice Burroughs won’t have a change of mind from reading this. For everybody else, these problems hardly seem worth the effort to mention. Of course a princess will need rescuing. Of course John Carter will hack through ludicrous numbers of enemies. Of course outrageous coincidences sometimes push the plot along. The book’s primary flaw is that it’s an exemplum of its author’s style. If you don’t like his style, you won’t like it when it is at its purest.

The problems of The Gods of Mars are the standard problems of most ERB books: simple chase mechanics, some clunky language, outlandish plot coincidences. Readers who don’t like Edgar Rice Burroughs won’t have a change of mind from reading this. For everybody else, these problems hardly seem worth the effort to mention. Of course a princess will need rescuing. Of course John Carter will hack through ludicrous numbers of enemies. Of course outrageous coincidences sometimes push the plot along. The book’s primary flaw is that it’s an exemplum of its author’s style. If you don’t like his style, you won’t like it when it is at its purest.

By the way, those telepathic powers that John Carter used occasionally in A Princess of Mars? Gone. Never mentioned here.

Let’s see, what else? The method of getting John Carter back to Mars is not that inventive; it only repeats what the first novel did. Sometimes Carter’s bragging gets overwrought. The attempt to disguise Carthoris’s identity for a big reveal is clumsy. The action scenes at places feel a bit too big, too outrageous. There’s some lag in the middle of the Act III.

But none of this matters much. I needed to fill out this section and pretend to have some objectivity. Seriously, I got nothing else. I love this damn book.

Craziest bit of Burroughsian Writing: “The plant man was well muscled, heavy, and powerful, but my earthly sinews and greater agility, in conjunction with the deathly strangle hold I had upon him, would have given me, I think, an eventual victory had we had time to discuss the merits of our relative prowess uninterrupted.”

Best Moment of Heroic Arrogance: John Carter and Carthoris fight side by side to cut down hundreds of First Born and white apes in an arena.

Times a “Princess” (Female Lead) Gets Kidnapped: 6 (counting the cliffhanger)

Best Creature: The plant men, one of the most hideous of Burroughs’s creations.

Most Imaginative Idea: A tie between the culture of the Valley of Dor and the culture of the Sea of Omean. Both could carry an entire book on their own.

Who’s Missing? Woola! What happened to Woola?

Should ERB Have Continued the Series? Absolutely. This is great, and it ends on a cliffhanger.

Next: The Warlord of Mars

Ryan Harvey is a veteran blogger for Black Gate and an award-winning science-fiction and fantasy author. He received the Writers of the Future Award in 2011 for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and has two stories forthcoming in Black Gate, as well as a currently available e-book in the same setting. He also knows Godzilla personally. You can keep up with him at his website, www.RyanHarveyWriter.com, and follow him on Twitter.

Great review Ryan, I need to put this back in re-read queue. It’s been way too long. Looking forward to The Warlord of Mars.

I’m the happy owner of a Doubleday hardback two-fer with the Gods of Mars and the Warlord of Mars.

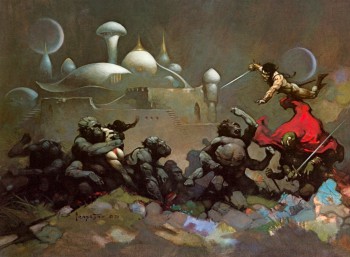

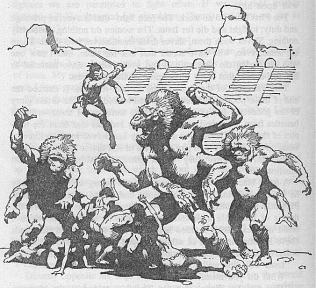

It has the Frazetta black and white illustrations too! (like shown above)

It’s no where near as old or awesome as what you describe having (I can’t imagine) but it was one of the first “grown-up” books I ever got … although I can’t recall for sure who gave it to me. Probably my Uncle Joe.

It’s been ages since I read it though, might be time for a revisiting.

Looking forward to the next installment as well!

I don’t own the that Doubleday combo of The Gods of Mars and The Warlord of Mars, but I have fond memories of it, because the first time I read these two novels was in that edition, which I borrowed from the Santa Monica library. I have my combos (Book Club Editions) for the rest of the series. I also bought the recent Book Club combos, which put three books in each, so the John Carter “trilogy” sits together nicely in a single volume titled Under the Moons of Mars, so the original title of A Princess of Mars gets to live again.

Just a heads up, the next installment won’t be this coming Tuesday, but the one after that, since I have a different topic slotted for this week.

[…] only a few chapters until they are defeated, or else they eventually switch allegiances; Phaidor in The Gods of Mars and The Warlord of Mars is the best example of the latter. But at his finest, Burroughs doesn’t […]

[…] Maybe that cult following is going to happen after all. As for whether this means we’ll see The Gods of Mars on screen… chances still not high on […]

[…] could one day triple the value of the book.” This makes me feel stronger about the 1924 copy of The Gods of Mars that I own, which has a dust jacket in horrible condition… but it does have the dust […]