Special Fiction Feature: “The Moonstones of Sor Lunarum” by Joe Bonadonna

Back on August 9, 2011, I wrote an article entitled “Dorgo the Dowser and Me,” which John O’Neill graciously posted on the Black Gate website here.

Back on August 9, 2011, I wrote an article entitled “Dorgo the Dowser and Me,” which John O’Neill graciously posted on the Black Gate website here.

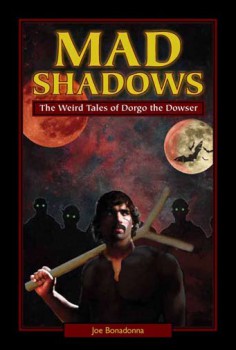

It was all about my first published novel of swords and sorcery, Mad Shadows: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser, the influences that inspired the book, plus some teaser “trailers” about each story. Mad Shadows is really a picaresque novel — a collection of six stories linked together by a main character, and a cast of recurring characters. While the first three stories are somewhat humorous in tone, they contain all the ingredients of sword and sorcery fiction: magic, mayhem, monsters, and murder. The final three stories are darker, grimmer, and deal with loss and tragedy.

Mad Shadows: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser can be purchased online at Amazon.com, Barnesandnoble.com, or directly from the publisher, at iuniverse.com. It’s available in hardcover, trade paperback, and as an eBook for both Nook and Kindle.

The story I’ve chosen for the Black Gate website is “The Moonstones of Sor Lunarum.” This is the third story in the book, and the only one not told in first person. While it contains its share of humorous scenes and amusing characters, the theme is one of loss. And of course, the shadow of death is constantly lurking in the shadows…

The Moonstones of Sor Lunarum

By Joe Bonadonna

This is a Special Presentation of a complete work of fiction which originally appeared in Mad Shadows: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser. It appears with the permission of Joe Bonadonna, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Copyright 2010 by Joe Bonadonna.

1: Night in a Cemetery

Long before the legendary cities of Cush and Erusabad were destroyed by war, the graveyard was old. Long before the fabled land of Attluma sank beneath the sea, it was old. And it was old before the halflings came to this land from another world. No one knew how old the graveyard truly was, for the carvings on its headstones and markers had been long worn away by the hands of time, wind, and weather. The cemetery crouched with its dead in a hidden vale in the dark heart of Khanya-Toth, land of shadows, black magic, and creatures of the night.

Urlak Blunker spat on a forgotten grave, and then glanced nervously at his brother Ollo. A graveyard at night was the last place either of them wanted to be.

The shadows of crumbling headstones danced like a troupe of drunken demons under the ice-white arc of a crescent moon.

They were sitting on one side of a small campfire in a clearing at the edge of the cemetery, near a cluster of ancient willows. A tall, slim woman sat on the opposite side of the fire, close to the entrance to her bamboo hut. She wore a black robe, her face partially hidden within its hood. A red velvet pouch hung from her black leather belt.

“You’ve come a long way from Valdar to see me,” she said. Her name was Zomandra Chuvai, and she was a witch, one of the Kha Jitah. She lived alone in that ancient graveyard, with only ghosts and memories to keep her company.

“Indeed we have,” Urlak said. He was a bald, rotund man with a pockmarked face and scraggly beard. “Deto Lepyr sent you word of our coming, I believe.”

“We’re the Blunker boys,” Ollo said. He was all skin and bone, with a sickly yellow pallor.

Urlak silenced him with an angry look. He smiled at the woman. “You’ll have to pardon my baby brother, Kha Zomandra. He’s all tongue and no ears.”

Behind them, three horses stood tethered to a tree, where a third man who had a wooden leg, a man named Klor Lugo, kept them company.

“I’m well aware of who you are,” Zomandra said. “Shall we talk business?”

“That’s why we’re here,” Urlak replied.

The witch lowered the cowl of her robe, revealing her face. She would have been pretty if not for the hole where her left eye should have been. Her other eye was as yellow as a cat’s… a tiny sun burning in a bony cave.

The Blunkers cringed at the sight of her. Klor Lugo never saw her face.

“Can we see the moonstones?” Ollo asked the witch.

“Shut up, Ollo! I’m older than you. I do the talking here.” Urlak shook his head and spat into the fire. “We’d like to see the moonstones first, if you don’t mind, Kha Zomandra.”

The one-eyed witch smiled. “Of course you would.” She stood and reached into the red velvet pouch with first her left hand, and then her right. In each she held what looked like a turquoise diamond about the size of a hen’s egg. Each had a crimson core, as if a single drop of blood had been encased within.

The brothers gaped at the sight of the gems, and grinned at each other.

“How do we know they’re the real thing?” Urlak asked the witch.

“Perhaps this will convince you,” she said, tossing the jewels into the fire.

The Blunkers cried out in alarm.

The jewels writhed and wailed as if they were unearthly creatures suffering great pain.

The horses reared and neighed in fright and tried to bolt. Klor fought to control them. He and Urlak exchanged quick glances.

Ollo covered his ears and whimpered like a frightened child. “Enough!” he yelled.

“We’re convinced,” Urlak said.

Zomandra rolled up her sleeves and reached into the fire to remove the moonstones. Neither her flesh nor the jewels were harmed. The unearthly wailing ceased, the horses settled themselves, and the night grew quiet again. Only the crackling of the flames could be heard, a chorus of laughing devils frolicking in the night.

Hiding the moonstones in the pouch again, Zomandra studied the night sky, the crescent moon, and the scattering of stars. She toyed with a silver pendant that hung from her neck: a pair of crossed lightning bolts, bisected by a trident. Finally, she returned her attention to the Blunkers.

“I’ll have nothing to sell until the next full moon,” she told them.

“How — how much for the two you have?” Ollo asked timidly. He looked at his brother, expecting to be chastised again. But Urlak nodded rare approval.

The witch laughed. “The demon Lunari that provided the moonstones asked for one of my eyes in exchange.” She glared at the two brothers with her cat’s eye. “Are you willing to replace what I lost, with one of your own?”

The gulp that erupted from Ollo’s throat was a blasphemous sound in the graveyard.

Urlak barked a laugh of false bravado. “And which color would you like to have, woman? The baby blue of my brother’s? Or the green of my own?”

“Look at the color of my eye. Do you think I care?” Zomandra asked. “No matter. These two moonstones are not for sale. Not at any price.”

Urlak nodded to Klor, who took a knotted leather cord from his pocket. He wrapped the ends around each hand.

“That’s fine by us,’ Urlak said. “We don’t have any money.”

Klor lurched forward without warning, wrapped the leather cord around Zomandra’s neck, and snapped it tight. She looked surprised as her legs kicked and her arms flailed in a futile struggle.

Urlak pushed his brother toward the witch. “We’re in this together, Ollo. It’s your turn.”

Almost reluctantly, Ollo drew his sword.

“Don’t be afraid,” Urlak said. “I’m right behind you.”

Zomandra looked Ollo straight in the eye as he plunged his sword deep into her bowels.

Klor loosened the leather garrote, and Zomandra fell to her knees. She choked on her own blood, but she didn’t scream, not even when Urlak used his brother’s sword to cut her throat. Before she died, she whispered strange words in her native tongue.

“Let’s ride!” Klor said.

Urlak tossed his brother’s sword back to him, but Ollo failed to catch it. “Clumsy idiot! Wipe it clean before you sheathe it — and put out that fire!”

While Klor untethered the horses, and Ollo put out the campfire and took care of his sword, Urlak relieved Zomandra’s corpse of the red velvet bag.

“Never trust a Blunker,” he sneered, kicking the dead witch. He didn’t take her silver pendant, however; he feared it would only bring bad luck, all splattered with her blood as it was.

2: Morning in a Mortuary

In the House of the Dead, only Dorgo and Captain Cham Mazo were still breathing.

Barely awake, belly growling, pockets all but empty, Dorgo’s mood was about as sweet as a rotten apple. But the Captain of the Purple Hand had need of his services, and being a pillar of the community, the Dowser could hardly refuse his summons to the Beggar’s Field mortuary.

On the other hand, Captain Mazo was in an unusually good humor because his only daughter had come back home after the troubadour she’d run off with abandoned her in a gambling house a few weeks earlier. Not even the dead man lying on the stone slab could sour his mood.

“I can’t understand it,” Mazo said. “There was a little blood on the cobbles where the body was found, but barely a drop left in him. Looks like something fed on the poor bastard.”

The victim was a middle-aged man, well dressed, well manicured, and obviously well off. If not for the fact that his throat had been completely shredded and his chest ripped open from breast to navel, he would have been just another corpse found lying on a street in Valdar.

“Unlike the bell ringer who used his head, this man’s face doesn’t ring a bell,” Dorgo said. “Any idea who he is? Or used to be?”

“His name was Deto Lepyr,” Mazo said. “He was from Khanya-Toth. Thief. Smuggler. Assassin. You name it, he did it. Lately, he’d been peddling Venom.”

Dorgo whistled in that graveyard house. “Interesting.”

Venom, milked from the fangs of an egg-bearing white cobra, then diluted with wine, made a powerful narcotic and aphrodisiac. It was very popular among both commoner and aristocrat.

“Aren’t you going to use that witchbone of yours?” Mazo sounded like a little boy asking a clown to perform some tired old trick.

Removing the Y-shaped yew branch from the quiver on his back, Dorgo gripped its bottom stem, and pointed the other two forks at the corpse. He felt only a slight vibration; no burst of heat or energy, no ectoplasmic residue. The dowsing rod was cold to the touch, which meant that whatever had killed this man was either human or something . . . unknown.

Dorgo replaced the rod in its weathered old quiver. “There are no demonic traces, no odylic echoes. Nothing to suggest that magic played a role in his death. If there’s something supernatural involved, then it’s something the rod can’t detect. Something I’ve never encountered before.”

“But his heart, Dowser!” Mazo said.

Dorgo’s stomach groaned at the thought of the force that had been used to rip open the man’s chest and tear out his heart. “So I’ve noticed. It’s as if some rabid beast had attacked him.”

“Beast? You mean — like a werewolf?”

“There was no full moon last night, Cham.”

“A ghoul?”

Dorgo smirked. “Ghouls like their meat dead and rotting.”

“Zombies?”

“They’d have stripped the flesh from his bones and eaten his brain.”

“And the loss of blood… are we talking vampire?”

The Dowser shuddered over that possibility and wiped the sweat from his brow; the mortuary was stifling hot, its stench composed of exotic spices, stale air and… well… dead bodies.

“A vampire is a very fastidious killer,” he said. “Three tiny puncture wounds, in a triangular pattern, is the mark of the vampire. Blood is sacred to them. They don’t spill or waste a drop. They rarely drain their victims dry, and they don’t run off with the hearts.”

Mazo sucked air through his teeth and let it out in a slow exhalation. “Then tell me what you think we have here.”

“Just what it looks like. A brutal murder. A robbery gone bad.”

“But Deto wasn’t robbed.” Mazo tossed a small, leather purse to Dorgo.

Catching it in one hand, Dorgo noticed that it was still wet and sticky with blood.

“I removed it from his belt before you got here,” Mazo explained. “Didn’t want it to turn up missing. Clues and all that, you know.”

Dorgo threw the dead man’s purse back to Mazo, and then wiped his hands on his trousers.

“Could be an assassination or a revenge killing,” Mazo suggested.

“I’ll go along with that,” Dorgo agreed. “This man was in a dangerous line of work. I’m sure he’d made a few enemies at one time or another.”

Mazo began tossing the purse into the air and catching it like some theatrical crook flipping a coin. The blood didn’t appear to bother him. “Maybe we’ve got ourselves a thrill killer. A real sick bastard. Remember that one madman who liked to rearrange his victim’s faces, sewing the eyes to replace the nose, using the lips for ears and the ears for lips?”

“I was hoping to forget that one,” Dorgo said.

Both men had known killers who collected the heads of their victims, crazed butchers who ate their victims after hacking them to pieces, or made clothing from their skins. The city of Valdar was a cesspool where all manner of deviates, maniacs, and lunatics gathered. Death by misadventure or design was all part of daily life in Valdar. Murder was a constant, whether for pleasure, profit, love, or revenge.

Dorgo plucked a stray thread from his shirt. “I’m afraid you may be right.”

Mazo shook his head. “You really need to find some clothes that aren’t so worn and out of fashion. Here.” He tossed the dead man’s purse back to the Dowser.

“What other suggestions do you have?” Dorgo asked.

“Keep your eyes and ears sharp. Stick your nose where it doesn’t belong.”

Dorgo jiggled the purse. “I’ll have this cleaned and returned to you.”

3: At Home with the Blunkers

The Blunker boys were neither the smartest nor most successful rogues in Valdar. They were just another pair of petty crooks in a city where honest men were almost as rare as two heads on a three-legged monkey. Ordinarily, Dorgo would have had nothing to do with them. But he had to learn what they were up to when they asked to meet with him regarding some exotic jewels.

Urlak poured himself a cup of wine, then filled a second cup and slid it across the greasy table. He gulped his wine and emitted a belch that sounded like a dragon breaking wind.

“What do you know about moonstones?” he asked.

Dorgo toyed with his wine; he didn’t want any on an empty stomach. “I know they’re extremely rare and worth a virgin’s ransom. Legend has it that there’s some magical element to them. But no one seems to know their origins or how they’re mined.”

With a smile a snake would envy, Urlak leaned across the table. “Now, you know that I know that you know some wealthy people who collect such valuables. Folks who might be willing to pay a fair price for a moonstone or two. That’s why you were invited to our humble home.”

Humble indeed! Dorgo thought.

The Blunker home was an old cottage built of log, stone, and mortar. It might have been quaint and cozy, once upon a time. But now it was a field of battle where piles of dirty clothes and layers of dust waged war against cobwebs, various insects, and foul-smelling refuse. The stench alone was enough to make Dorgo retch; it was worse than the mortuary. The place could be called a pigsty, but calling it that would be an insult to all pigs.

“What you propose sounds interesting,” he said. “But I’ll need to see the moonstones. I’ll have to test them in order to determine their authenticity.” Having never seen a moonstone, he wouldn’t know one from a coconut. But if it was true that the jewels did possess some magical properties, his dowsing rod would pick up on that.

Urlak sat back and stared at Dorgo for several heartbeats. “Back in a moment.”

He got up and headed downstairs through a rickety door at the back of the room.

While he waited, Dorgo looked out a filthy window.

The Blunkers’ cottage sat on a flat rise high in the Knuckleback Hills, a few hours ride south of Valdar. To the north, Skullcap Mountain rose like a waking god from the heart of Marl Valley. To the south, the main road from Valdar cut through the hills and angled west through the Backbone Mountains. A narrow trail branched off from the road and wound its way to the stony yard in front of the cottage. A tall, lonesome cactus stood sentry duty in the front yard.

Urlak returned a moment later, carrying a red velvet pouch in one hand and a sheathed sword in the other. Setting the sword on the table, he opened the pouch and dumped its contents next to it. He belched loudly, grinned proudly, and folded his arms across his chest.

Dorgo studied the two jewels on the table. About as large as hens’ eggs, they looked like turquoise diamonds. But at the core of each was a blood-red speck, like a heart in miniature.

“These could be made of glass or crystal,” Dorgo said.

With a gruff laugh, Urlak unsheathed the sword and said, “Think so? Then watch this.”

Raising the sword high above his head, he brought the blade down hard and fast on one of the moonstones. Several things then happened in rapid succession.

The moonstone wailed like a castrated coyote and flew off the table. The sword snapped in two, and the upper half sailed across the room. Footsteps pounded up the stairs behind the back door. Voices shouted and cursed as the door crashed open. Ollo barged into the room. The flying moonstone hit him on the forehead, and down he went. The broken half of the sword missed cutting him by the width of a gnat’s hairy leg and buried itself in the door. A moment later, a woman charged through the open door, hands tied in front of her.

“I’ll poke your eyes out!” she shouted. “I’ll bite your ears off!”

Then she tripped over Ollo and fell flat on her face.

Dorgo leapt to his feet, ready to draw steel.

Urlak retrieved the moonstone and kicked his brother savagely. “Dumb ox! I told you to gag the wench and put a hobble on her.”

“Sorry, Urlak.” Ollo rose shakily to his feet, rubbing his bruised brow. He looked around, as if in a daze. “Oh, hello, Dowser.”

“Shut up, Ollo!” Urlak yelled. “Now tie and gag that girl properly.” He hauled the woman to her feet and threw her into a chair. Then he set the jagged end of the broken sword against her throat. “One little peep out of you, girl, and you’ll never peep again,” he warned.

Ollo quickly tied the woman’s legs together and gagged her with his dirty kerchief.

Dorgo watched all this with a hand on his own sword, having no idea what he should do. The Blunkers may be idiots, but they could be as dangerous as two cornered goblins. So he remained silent… and almost forgot about the moonstones when he realized he knew the woman.

She looked younger than her twenty and nine years. She was tall and willowy, with small breasts and narrow hips. She had long red hair, bright green eyes, and lips that should be kissed at least once a day. Dressed in black leather, she looked like an assassin or a cat burglar. When she glanced at Dorgo, recognition and hope lit her eyes — eyes that pleaded for help.

When Ollo finished securing his captive’s bonds, Urlak tossed the broken sword on the table. “Take her back down to the cave,” he told his brother. “Stay with her. If she gets loose again, I’m not going to be so forgiving.”

“No!” Skinny and sickly-looking as he was, Ollo’s voice shook the room. “You’re not going to hurt her and you can’t force me to do to her what you made me do to that —”

Urlak slapped Ollo into silence.

The woman shot Dorgo a worried look.

“You didn’t have to hit me,” Ollo told Urlak, rubbing his cheek.

“Your mouth is too big for your brains, little brother.”

“It’s bad luck to kill her. She didn’t do nothing.”

“She tried to rob us, you moron!”

“So let’s make her our slave, Urlak. She can cook and clean for us. And she can’t eat all that much. I mean, look how skinny she is.”

Urlak let out a long sigh of frustration. “Please, just take her downstairs so’s I can finish my talk with Dorgo. Can you do that for me without mucking it up?”

Ollo then noticed the broken sword lying on the table. “That’s my sword!”

“You won’t need it — not if that girl behaves herself. Now go do what I told you to do.”

“Don’t I always do what you tell me to do?” Ollo picked up the girl, tossed her over a shoulder like a sack of flour, and left through the rear door.

Urlak slammed the door shut. “You’ll have to forgive my little brother,” he told Dorgo. “He was kicked in the head by a drunken unicorn when he was a baby.” He set the moonstone back on the table, next to its twin. “Now… where were we?”

“I was about to inspect the moonstones,” Dorgo said.

“Be my guest. That hoodoo branch of yours can’t hurt ’em none.”

Dorgo slipped the dowsing rod free of the quiver on his back. Then, just as he’d done at the mortuary, he gripped the rod by its bottom stem, and pointed the two shorter tines at the moonstones. He wasn’t at all surprised to feel the heat, the energy, and the vibrations emanating from the jewels. They were definitely not ordinary diamonds. In fact, the moonstones were not of earthly origin at all, from what he could tell, and they did possess some inherent magical properties. But the truly odd thing about the stones was that they were more organic than some form of crystalline mineral. It was as if they had once been part of a living thing, the same way a severed hand was once part of a human body.

Satisfied, Dorgo replaced the dowsing rod in its quiver.

“Did you get your reading?” Urlak asked.

“Indeed I did,” Dorgo said. “Tell me, how did you get your hands on the moonstones?”

“That, my friend, is a family secret. Don’t want no competition, see?” Urlak grinned. “Think you can find us a buyer among all them rich folks you know? We’ll cut you in fair and square.”

“I do know some people. I’ll have to talk to them.” Dorgo finally tasted the wine; he needed the false bravado. “So, tell me about the girl,” he added, setting the cup on the table.

Urlak frowned suspiciously. “Why? What’s she to you?”

“Nothing. Not a thing.”

“Well… she broke in here last night. Woke us up, too. I think she was looking for the moonstones. My brother’s got a big mouth. I was all for, you know —” Urlak traced his thumb across his throat. “But Ollo stopped me. He says he’s seen her around Valdar. I think he’s smitten with her, though he wouldn’t know which end is which, if you get my drift.”

“You want to kill her, but you don’t want to break your brother’s heart. And you certainly don’t want any blood on your hands.”

“I—n-no, no,” Urlak stuttered. “Wouldn’t want that at all. Besides, someone could be looking for her. If I kill her —”

“They might find out you did it.”

“Ah, you understand everything, Dowser. So that’s the predicament I’m in. If I let her go, she might blab about the moonstones, and then I’ll have every thief and cutthroat in Valdar sniffing around out here. You know, you just can’t trust people these days.”

“Amen to that,” Dorgo said. “Well, it’s a dilemma, to be sure. But there are ways of making the wench disappear, without resorting to murder.”

“Disappear? You mean — like by magic?”

Dorgo shook his head. “What I mean is, you can always sell her.”

“You ain’t thinking of buying her, are you?”

“Who? Me? No. She’s too skinny.”

“Then who we going to sell her off to?”

With a nod and a wink, Dorgo said, “I know a gentleman. His name is Vedun. Gonj Vedun. He procures harem girls for the sultan of Salukadia. He pays off in gold, too. No questions asked. No tales told. All very discreet.”

“Is he honest?”

“Why, he’d let his own family starve to death before he’d even consider stealing a loaf of bread to feed them. He’s in Valdar right now, as a matter of fact. I’ll speak with him as soon as I get back. How much will you take for the girl?”

“I’m not a greedy man, as you might think, Dowser.” Urlak plucked a nose hair. “How’s three thousand crowns sound to you?”

“Not loud enough. Make it five thousand. I want a bigger cut.”

Urlak laughed. “I like the way you think! How soon can you set this up?”

“Oh, let’s say sunfall, tomorrow. We’ll meet here. You approve?”

“Fine. That’s just fine. But don’t you go forgetting about the moonstones.”

“Come now, my fine fellow! If I’m in for a penny, then I’m in for the whole hog. You might as well set your asking price right now.”

“Ten thousand crowns, for the pair.”

Dorgo whistled. “That’s steep, but I think I can turn a deal.”

“Good. But I won’t sell them until after the next full moon.”

“That’s almost a week off. Why the wait?”

Urlak picked up the moonstones and replaced them in the red velvet bag. “Let’s just say that I’m superstitious when it comes to making certain deals before a full moon.”

“But we’ll do the girl tomorrow night, right?”

“Oh, that’s as good as done.” Urlak held out a hand. “Is it a bargain?”

“Indeed it is, it is indeed.” Dorgo clasped Urlak’s hand, and they tested each other’s grip.

Urlak picked up the broken sword and pressed the edge of it against Dorgo’s throat. “But if you cross me up, I won’t like you no more.” Urlak grinned and released Dorgo’s hand.

Wondering what he’d just gotten mixed up in for the sake of a pair of pleading eyes, Dorgo wiped his hand on his trousers.

4: The Big Dwarf

The Crimson Sand was a massive, three-sided coliseum built of red stone, just beyond Valdar’s city limits. Often referred to as the Triangle or the Sand, the hippodrome was the home of unicat, horse and chariot races, bullfights, and gladiatorial contests. But what made the Sand truly unique was that on a weekly basis, spectators could thrill to such events as unicorn fencing, satyr boxing, centaur racing, cyclops acrobatics, and the ever-popular minotaur wrestling.

The events were over for the day and the crowds long gone by the time Dorgo entered the Crimson Sand, but the arena was far from empty. Human gladiators worked out on the sand. Muscular satyrs wearing knee-length leather breeks pummeled each other with fists and cloven hooves. A trio of centaurs ran laps around the circular track, while a couple of statuesque unicorns engaged in a practice duel, using their horns as lances and fencing foils. Heading toward the entrance to the stadium’s hypogeum, Dorgo stopped to watch two minotaurs in loincloths rehearse their wrestling routine. The small minotaur used a fancy hornlock on the larger, then twisted his body, flooring his opponent and pinning him to the sand.

The hypogeum beneath the Crimson Sand was a world unto itself, a labyrinth of tunnels and chambers: offices and armory, apothecary and infirmary, kitchen and dining hall, gymnasium and stables, baths and chapel. Dorgo paused a moment to watch a trio of physicians tend to a lavender unicorn with a nasty slash on his left haunch. Amber blood stained the beast’s hide, and his bone-colored horn was broken off near the base of his skull.

“Hello, Jeke,” Dorgo said. “Something tells me I won again.”

The unicorn neighed menacingly. “Keep walking, Dowser,” he growled. “You’re a bloody jinx, that’s what you are. When my horn grows back I swear — I’m going to shove it up your ass until it comes out of your mouth!”

“Don’t blame me for your bad luck, Jeke. You were born jinxed.” Dorgo grinned. “But I hope we can still be friends.”

“Kiss my hindquarters, Dowser!”

The unicorn started yelling at the physicians, cursing their lack of competence. Dorgo laughed, shook his head, and continued on his way.

Turning down a lamplit corridor, he wondered how he was going to tell the Big Dwarf what he had discovered at the Blunker house.

A tall, young minotaur with short horns and red fur, and dressed like a gladiator, guarded the entrance to a private chamber. The halfling recognized Dorgo, nodded, and opened the heavy door for him. Dorgo nodded his thanks and went inside.

It was a quiet, comfortable room, softly lit with candles. A few chairs, a table, two chests, and a large cabinet took up space. The aromatic scent of eucalyptus oil and wisps of sweet-smelling tobacco smoke drifted in the air like fragrant ghosts.

Stretched out on a massage table was a huge, muscular minotaur, well over seven boots tall. His horns were long and as white as pearl, his bull’s head was as black as endless night. A gold ring glittered in his right nostril; in his left ear he wore a silver ring. The minotaur was smoking a pipe while a powerful centaur massaged his back and shoulders. The human half of the centaur was strong and handsome, and garbed in a leather apron. His lower body was that of a chestnut stallion. Both halflings looked up and grinned when Dorgo entered and bowed to them.

“Greetings, Vadid Simoth,” he said to the centaur. “How’s the leg?”

Vadid the centaur shrugged his massive shoulders. “On occasion, it will cause me some little discomfort. I thank you for asking, Dorgo.”

“You’re welcome.” Dorgo winked at the minotaur. “What’s news, bullman?”

The minotaur blew a trio of smoke rings. “I have new wrestling name, Dorgo. I am now Torok the Terrible. Was father’s name. How you like?”

“Very cute. Is that your brother guarding the door?”

“Young brother Shem, yes. In training at gladiator school.”

“How is trade these days, Dorgo?” Vadid asked.

“I was expecting something to turn up — and it did,” Dorgo replied. “Has the Weasel been around at all today?”

“Don’t call me that, Dorgo. You know I’m sensitive.”

Dorgo turned as the owner of that voice strolled into the room in a grand, theatrical manner, swatting the air with a gleaming rapier.

He stood just over four boots tall, had a bushy mane of curly brown hair, bright blue eyes, and a left ear missing its lobe. Though short in stature, he was perfectly proportioned and well muscled, and one of the best swordsmen in Valdar. He was also the manager of Torok the Terrible. His name was Heegy Wezzle, otherwise known as the Big Dwarf.

“Where’s my winnings, you spawn of an elf?” Dorgo asked him.

“Elves are mythical beings, you cretin,” Heegy said. “You may be taller than me, but I can cut you down to my size without breaking a sweat.” And with that, he lashed out with his rapier, slicing the top button off of Dorgo’s shirt.

“Bug you, Weasel! This is my best shirt!”

Heegy tossed a five-crown gold piece to Dorgo. “Go buy yourself a new one.” He hung the rapier on a wall hook. “Old Jeke Teuqaj took quite a beating today. Got his horn broke, too.”

Dorgo stashed the coin in the blood-stained purse. “I just had words with Jeke. Is he going to be all right?”

“He’ll be fine, if he listens to the physicians. His horn should grow back in two, three months. But he’s getting too old for the arena.”

“I don’t think he likes me anymore,” Dorgo said.

“You always bet against him, that is why,” Vadid explained. “He is very proud, and you must remember that for many years, he never lost a duel.”

“So what brings you to our cozy little lair?” Heegy asked.

“Do any of you know anything about moonstones?” Dorgo asked his friends.

Torok and Vadid exchanged glances. Dorgo noted it but said nothing. Heegy scratched his damaged ear and remained silent.

“From Khanya-Toth, they come,” Vadid said in a quiet voice. “Magical things, so it is believed by all our Kindred.”

Torok snorted in agreement. “We come from Khanya-Toth. Among our herds, many say witches make them. With magic. Use demons and unholy acts.”

“I had business once in Khanya-Toth,” Heegy said. He shivered as if a sudden chill had swept into the room. “Strange things can happen there.”

“It is not a land most humans find to their liking,” Vadid said.

Dorgo found these tidbits of information appetizing.

South of Valdar and the kingdom of Rojahndria, Khanya-Toth was a land of eldritch forests, vast deserts, hidden vales, and lost canyons. It was not a land of towns and cities, but an ancient wilderness where halflings and a small number of humans lived in clans, herds, and tribes. Khanya-Toth was a region where even the shadows feared what lurked in the darkness of night.

“Who sell moonstones?” Torok asked.

“A couple of shiftless rogues named Urlak and Ollo Blunker,” Dorgo told him. “They hired me to act as their agent. To find them a buyer.”

“I know who they are,” Heegy said. “Have you seen the jewels?”

“Saw them and tested them. They’re unlike any jewels I’ve ever seen. There is definitely something unusual about them. They seemed almost alive.”

Again, Torok and Vadid shared meaningful looks but said nothing.

“Wrestling and gambling, these are my passions, Dorgo,” Heegy said. “You know that. I don’t traffic in jewels of any kind.”

It was time to lower the boom, Dorgo told himself. He looked Heegy square in the eye, then hit him with just two words: “Elema’s back.”

The Big Dwarf went perfectly still. “Torok. Vadid. Please, leave us.”

Without a word, Torok the Terrible got off the table and wrapped a towel around his waist. The minotaur towered over Dorgo as he bowed, turned, and left the room. Vadid the centaur nodded farewell and limped after Torok, closing the door gently behind him.

The tension in the room was palpable. Heegy said nothing as he walked over to the cabinet, took down two glasses and a bottle of brandy, and motioned for Dorgo to sit at the table. After pouring brandy slowly into each glass, the Big Dwarf seated himself across from Dorgo.

“She’s a strange, wonderful girl,” he said wistfully. “When did you see her?”

“A few hours ago. At the Blunker residence.”

“What in Hell was she doing there?”

“Being held captive. Apparently, she was caught in the act of trying to rob them. My guess is she was after the moonstones.”

“That figures. There was always a touch of larceny in her soul.” Heegy took a long, thoughtful sip of brandy. His eyes burned like flames behind blue-colored glass. “Last I heard she took up with a knave named Deto Lepyr. He smuggles Venom up from Khanya-Toth.”

“Deto Lepyr is dead. Murdered. I examined his body this morning.”

“You think Elema could’ve done it?”

Dorgo shook his head. “Not the way he was butchered.”

“Did you speak with her?”

“No. I didn’t want the Blunkers to know that I know her. But she saw me.”

Heegy toyed with his brandy. “Did those monkey buggers hurt her?”

“No. I think they’re afraid of her.”

A gentle smiled played across Heegy’s lips. He tapped his left ear with a finger, the ear without a lobe. “I didn’t lose this in a duel, Dorgo. I lied about that. Truth is — Elema and I had a minor disagreement, the night she walked out on me. She… well, she bit off my bloody earlobe. That girl has one nasty temper.”

Dorgo raised his glass. “In Valdar, women are more dangerous than crossbows.”

Heegy touched his glass to Dorgo’s, and they drained their glasses dry. “Do you know what those two halfwits plan to do with her?”

“Urlak was all for killing her. But Ollo wouldn’t stand for it. Said it would be bad luck to kill her. I think there’s a lot more to this whole moonstone affair than I know right now. But I did manage to convince Urlak that the smart thing to do would be to sell Elema.”

“Are you crazy? She’s a skinny little thing. Who’d want to buy her?”

Dorgo winked. “Gonj Vedun.”

The Big Dwarf sat there with a look of amused disbelief on his face that Dorgo found most satisfying. “Think it’ll play well?” Heegy asked.

“I hope so. But I’m going to need your help with this, Weasel. And I have to go see Marlia. I’m going to need her help, as well.”

“Oh, I’m certain she’ll be interested in what you’ve got cooking. She and Elema… you see, there’s a bit of history between them two girls.”

“This I did not know. I thought you and Elema were — I mean, I wouldn’t have guessed that she sailed her boat without a mast.”

“Elema drops anchor in any port that can provide shelter for her.” Heegy sighed, a look of fondness and nostalgia softening his eyes.

Dorgo didn’t need his dowsing rod to pick up on his friend’s melancholy turn and conflicting emotions. “You still love her, don’t you?”

“She broke my heart, Dorgo.”

“She’s a woman. That’s what they do.”

5: Interlude at the Hoof and Horn Club

After leaving the Crimson Sand, Dorgo headed back to the city, his head filled with plans he had to make, plans he needed to make.

Walking the main road back to Valdar, he could see a magnificent white villa gleaming in the sun as he approached the turn-off leading to the city. The late-morning sun graced the white stone walls and ocher roof tiles of this sprawling estate. Surrounded by fur and pine trees, with two massive iron gates set in its main wall, it was an ode to rural tranquility.

Vadid Simoth was leaning against the wall next to the gates.

“Something tells me this is no chance encounter,” Dorgo said.

The centaur bowed gracefully. “That it is not. Your presence is required in the club. Jeke Teuqaj asks to share words with you.”

“I hope his horn hasn’t grown back already,” Dorgo said. He let out a long, weary sigh. “Lead on, Vadid. Lead on.”

He followed the limping centaur through the gates of the villa, past a great stone fountain in the likeness of a cyclops urinating into the pool of water. It was a cyclops of Clan Titantos who first brought the halfling games to the Crimson Sand, a century or so ago. This was Dorgo’s first visit to the club since the cyclops Urzool Lairo, was brutally murdered. Seeing that statue was a painful reminder of the night Urzool had died in his arms and how much he missed his friend.

The Hoof and Horn was a private club for the halflings of Khanya-Toth. It was also a rest home for retired or disabled veterans of the arena, as well as a hospice for the sick and dying. Other than gladiators, physicians, and nurses, few humans ever saw the inside of the villa. It was owned by Praxus Odetti, the satyr and retired pugilist who often posed as a blind beggar.

The common room was a massive chamber with various-sized chairs and tables, as well as three different counters to accommodate centaurs, satyrs, and minotaurs. Special troughs along one wall were designed to provide food and drink for the unicorns. There were also private stalls floored with straw and palm leaves where both the centaurs and unicorns could lounge in comfort. Lamps made of red, blue, orange, and green glass provided soft illumination.

The club was all but empty as Dorgo followed Vadid toward the stalls at the rear of the common room. A sultry faun in a purple robe served drinks to a pair of elderly satyrs playing chess at a table in one corner. At the smallest of the three counters, a human physician wearing a white smock flirted with a pretty dryad dressed in a green one. The aging minotaur tending bar looked bored as he yawned and lazily wiped the counter clean.

Vadid led Dorgo toward a private stall where Jeke Teuqaj, the lavender unicorn with the broken horn, reclined on a bed of fresh straw. Dorgo bowed and sat on a stool facing Jeke. Vadid leaned against the wall, hands in the pockets of his apron.

“Thank you for coming, Dowser,” the unicorn said.

“You hurt my feelings today, Jeke,” Dorgo said. “You were very rude to threaten me. I thought we were friends. Nevertheless, I’m glad you’ll soon be up and about.”

The unicorn stretched his left leg and winced with pain; there was a line of stitches on his haunch. “How do you think I feel whenever I hear word that you, my old friend, have bet against me? We unicorns are a very superstitious breed, you know.”

“There’s a lot of that going around today.”

“Why do you bet against me? Every time you do, I lose.”

“If I put my money on you to win, then I lose. I’m somewhat superstitious myself.”

Jeke whinnied in amusement. “Well, I shouldn’t blame you. Maybe I’m getting too old for the arena.” He sighed wearily. “Will you do me a favor?”

“Let me hear what it is, first.”

“Stop betting against me!”

Vadid laughed and stomped the floor with one hoof.

“I can do that,” Dorgo said with a grin.

“Splendid!” Jeke said. “Now, the reason I asked Vadid to bring you here is because he told me that you were asking about moonstones.”

Dorgo glanced at Vadid. “I thought centaurs minded their own business.”

“Then it is Jeke you should have first asked about moonstones,” the centaur told him. “Things he knows, you may need to know.”

“All right, Jeke,” Dorgo said. “Talk to me.”

“Did you know that ages ago, the unicorns taught humans the ways of magic?” Jeke asked.

“So I’ve heard. What’s that have to do with moonstones?”

“By my father’s hooves!” Vadid said. “Listen and learn, Dorgo.”

Jeke nodded his great head. “You see, when the Kha Jitah rose to power, they turned against the unicorns. The Kha Jitah cast a spell that wiped knowledge of the occult from their minds. When it was over, my ancestors remembered nothing of magic — except to fear and to shun it.”

Dorgo had heard of the Kha Jitah. They were a secret order of witches: the Sisterhood of the Cowl. And witchcraft had its origins in the dark, primeval realm of Khanya-Toth.

“Does the Kha Jitah hold the secret of the moonstones?” Dorgo asked.

“One among many secrets,” Jeke said. “Though they stopped us from using magic, they could not take away all we know. Bits and pieces of our lost knowledge still remain to us, like flotsam and jetsam in our memories.”

“I know that moonstones don’t come from this world,” Dorgo said. “And I know they possess some kind of odylic power. What I want to know is—what are they and where do they come from? How would the Kha Jitah use that power?”

Jeke gave Dorgo a long, penetrating look. “Moonstones are actually the testicles of demons called the Vah Lunari.”

“Tell me you’re joking.”

“I swear by the horns of my forefathers, I am not.”

Dorgo had some knowledge, some experience with the entities of the Vahjna Sorai—the demonic realms of the multi-dimensional cosmos known as the Echoverse. But this was something new to him, something he’d never heard of.

“That explains the power I sensed through my dowsing rod,” he said.

“The Lunari are from the demonic Otherworld called Sor Lunarum,” Jeke explained. “As with any invocation, blood is required to summon these demons. But they demand a body part from anyone who calls them from their world. In exchange, the demons perform self-castration.”

“Incredible!” Dorgo said. “Why would these demons agree to such mutilation?”

“Because human flesh, human blood, and bone are a rare, magical delicacy in their world.”

Dorgo shook his head, amazed by what he’d been told. “Whatever power these demon scrotums possess . . . can it really be worth the loss of an arm or leg?”

“Only the Kha Jitah can answer that,” Jeke said.

“They must know how to harness that power, whatever it is. How to use it,” Vadid said. “They are a most dangerous breed, the Kha Jitah.”

“I know,” Dorgo agreed. “And unsuspecting people think that moonstones are just some rare form of jewel. They’ll pay a fortune to own a pair.”

“Maybe they are safe, not knowing what power the moonstones possess,” Vadid said.

“I can only hope that’s true.”

“We ask no questions, Dowser,” Jeke said. “Just be careful. There may be more to moonstones than what little we know and have told you . . . more than we can guess.”

“You’ve been most kind and very helpful, Jeke,” Dorgo said. “Thank you.”

“I wish I knew more,” the unicorn said. “Just remember this: what is spawned in the shadows of Khanya-Toth lives only in the night ever after.”

Something crawled up the back of Dorgo’s neck. He reached to slap it and then realized it was only the ghostly chill conjured by Jeke’s words.

6: An Afternoon at the Theater

The Glass Wolf was Valdar’s most successful and critically acclaimed theater. It boasted a troupe of accomplished thespians who had come from all across the continent of Aerlothia to audition for the Wolf’s talent manager, hoping to win a spot in the theater’s repertory company.

There was no matinee that afternoon when Dorgo entered the theater. But a handful of actors and actresses were on stage, rehearsing a scene from The Thief of Souls, a new play by the noted playwright, Quiversword. Dorgo paused to watch the bald director throw a tantrum, insult everyone on stage, then collapse in a chair to sulk. It brought back fond memories of the brief time when Dorgo had basked in the glow of the footlamps.

Heading backstage, Dorgo knocked on the door to the manager’s office.

Marlia Hivalna opened the door a few heartbeats later. She removed her eyepieces, took a long look at Dorgo, and shook her head in amused disgust.

“Wipe your feet and don’t touch anything,” she said.

“You sound like my mother.”

“I thought you were an orphan.” She stepped aside to let him in.

Dorgo grinned, pinched her cheek, and sat in a chair facing her desk.

The desk was cluttered with an abacus and ledgers, quills and inkpots, a pot of tea and a half-empty cup. On one corner sat a handbow: a small crossbow that could be held and fired with one hand. It was locked and loaded with two bolts, each with its own trigger. Hanging on one wall was a target. Dorgo picked up the handbow and took aim at the bull’s eye.

“That is not a toy,” Marlia said as she snatched the weapon from his hand. She put it back where it belonged and sat down behind her desk.

She was a small, lusciously plump brunette, and she exuded a sexuality that took Dorgo’s breath away. The plain, blue dress she wore accented her ample bosom and matched the color of her eyes, which revealed an intelligence he found attractive as well as intimidating.

“You owe me five crowns, Mikawber,” she said.

“Don’t tell me that flea-ridden Trollchaser actually won?”

“By a whisker in the fifth race at Triangle.” Marlia donned her eyepieces. “So pay up, or I’ll be forced to exact my pound of flesh.”

Cursing his ill luck, Dorgo opened the blood-stained purse and gave her the five-crown piece he’d won from Heegy.

“That reminds me of the time I played Shay in your very first production of The Merchant of Valdar,” he said. “I was quite good, wouldn’t you say?”

“You were terrible. And the play closed after three performances.” Marlia laughed and sipped her tea. “Well, don’t just sit there like a bit player who can’t remember his next line. Speak up so they can hear you in the balcony.”

“I need your help, Marlia.”

“An old plot device. But let’s see how it plays to the crowd, anyway.”

“When was the last time you saw Elema Jorn?”

Marlia regarded him thoughtfully. “About a month ago. We talked about getting back together, but then she ran off with some bastard named Deto Lepyr.”

“Well, Deto’s as dead as my dream of being a great actor. He was murdered.”

“My God! You don’t think that she —”

“No, I don’t,” Dorgo said. “She probably doesn’t even know he’s dead.” He then told her everything he knew thus far regarding the moonstones, the Blunkers, Deto Lepyr, and Elema Jorn.

When he finished talking, Marlia sat there, shaking her head. “Elema never said anything about moonstones. I thought they were just a myth.”

“They’re real, all right. What else can you tell me about Deto and Elema?”

“She and I had an understanding,” she explained. “When she went off with Heegy, I wasn’t upset. It was just something she felt was right for her at the time. We stayed friends. But I warned her about getting involved with that Deto again. Damn her!”

Marlia picked up the small handbow, unlocked the safety, and fired both bolts in rapid succession at the target on the wall. There was a hissing sound as the bolts sliced through the air, followed by two thuds as both landed dead-center in the bull’s eye.

Setting the weapon back on the desk, she pushed her tea cup aside and leaned forward, elbows on the desk. Anger and worry were two shadows warring across her face.

“Elema and Deto were involved in smuggling Venom, you know,” she said.

“I know, and that’s a thread that leads back to Khanya-Toth,” Dorgo said. “Venom comes from there. So do moonstones. Now, Deto was found dead this morning. Then Urlak tells me he’s selling moonstones. And then I find out that Elema was caught in the act of robbing the Blunkers.” He sighed and rubbed his crooked nose. “It’s been one Hell of a day, so far.”

“You’ve had worse, I’m sure. So either Deto was killed because of a Venom deal gone wrong or because of the moonstones.”

“One thing’s for sure, the Blunkers have nothing else worth stealing.”

“Except moonstones.”

Dorgo nodded. “Exactly.”

“How did Elema find out about them?”

“Take a guess.”

The look in Marlia’s eyes told Dorgo that the plot lines were turning inside her head. “My money’s on Deto Lepyr,” she said. “I think he was the leading man in this mystery.”

“That’s what I’m thinking. But we won’t know for sure until we get Elema safely away from the Blunker boys.”

Marlia’s fingers tapped her desktop. “Is this the scene where I make my entrance?”

“Blazes, woman! I swear — you have greasepaint for blood.”

“Call it a minor affectation. I’m a frustrated thespian with no talent for treading the boards.” Marlia chewed a fingernail. “Seriously, Mikawber. I’m worried. The Blunkers may be idiots, but don’t turn your back on them. Especially Urlak. He’s an animal.”

“He makes me nervous, too,” Dorgo admitted. “And he may decide it’s a much safer bet to just silence Elema. Permanently.”

“Please — don’t even suggest such a thing.”

“I’m sorry, love. But that’s the cold, hard fact of it.” Dorgo took note of the worried look in her eyes. “You really love her, don’t you?”

“It shows, does it?”

“Like too much kohl under the eyes.”

“What about Heegy?”

Dorgo scratched the scar on his cheek. “He has his own role to play.”

“I mean, is the Big Dwarf still in love with her?”

“What do you think?”

“And what about you?”

Dorgo sat back and smiled. “One night, shortly after I first came to Valdar, I got very drunk at Kortono’s Cave, and someone picked my pocket.” He laughed at the memory. “Later that night, two rogues dragged me into an alley and were about to cut my throat because I had nothing for them to steal, except my boots, my sword, and my dowsing rod. Then someone came along and chased the would-be cutthroats away.”

“Would that someone who saved your neck be our own little Elema?”

“She’s real good with a knife and she can kick like a satyr.”

“That’s my girl! So . . . what part do you want me to play?”

Dorgo grinned. “Do you still have that chest of iron pyrite coins? The one that was used in last season’s production of The Treasure of Colossus?”

“The fool’s gold? Yes, it’s in storage with all the other props.”

“Good. I’ll need it. You probably won’t see it again.”

“It won’t be missed. Now tell me — what’s the plot?”

“Let’s not raise the curtain just yet. I need to look at your wardrobe, first.”

Marlia looked at Dorgo as if he had suddenly grown a pair of antlers. “Sometimes I worry about you, Mikawber. You want to borrow some of my clothes?”

“What I want is to look through the theater’s wardrobe department.”

7: Another Day, Another Corpse

Dorgo had just sat down at his table in the Hungry Hyena when a customer came in and announced that there was a body lying in the alley out back. As the owner of the eating house rushed off to fetch the constables, Dorgo went out through the kitchen and into the alley.

The neighborhood was quiet, the streets deserted as he knelt to examine the body. He had a feeling that the corpse might have been left there for him to find. Maybe the killer or killers knew where he ate breakfast almost every morning.

The man had been murdered in the same fashion as had Deto Lepyr: chest ripped open, heart torn out, blood almost completely drained. The dead man also had a wooden leg, which had been torn loose and was lying beside him. From the looks of it, and the condition of his skull, the wooden leg had been used to bash in his head. Dorgo knew who the dead man was: Klor Lugo, a petty thief, quick with a garrote; he’d also been strangled with his own knotted cord. Lugo had been known to associate with the Blunker boys.

On closer examination, Dorgo saw that Klor held something clutched in his left hand. He pried open the clenched fist and found a silver pendant on a broken chain: a pair of crossed lightning bolts bisected by a trident. It looked vaguely familiar, though he couldn’t place it. Holding that pendant sent a chill through his bones; it reminded him of a pewter Alacrux and a mummified body he’d found lying on the roof of the old caravansary.

No human had killed Deto Lepyr and Klor Lugo, of that he was fairly sure. And he was dead certain that the Blunkers were somehow at the heart of it . . . and that it all trailed back to the moonstones and something that had happened in Khanya-Toth.

That strange realm had a long, dark history. No foreign power had ever conquered her. Five hundred years ago, the Estaerine Church in Dasheeria, which borders Khanya-Toth to the east, declared jihana—a holy war against that shadowed land of mystery. It was the last time an outside force attacked Khanya-Toth. It was also the last anyone had ever heard of the Army of the Jihana.

As Captain Mazo guided his growling unicat into the alley behind the Hungry Hyena, Dorgo slipped the pendant into a pocket. He rose slowly to his feet.

“This is getting to be a bad habit,” Mazo told him.

“I’m not very fond of this routine myself,” Dorgo replied.

The Captain of the Purple Hand dismounted, holding his unicat’s reins in one hand. The huge feline hissed at Dorgo, its long horn like a deadly lance. Mazo laughed at that. The Dowser had about as much love for the temperamental beasts as he did for boils on the buttocks.

Mazo gave the corpse a quick looking over. “As dead as Deto Lepyr. Killed the same way, too. You know him?”

“Never saw him before.” Dorgo lied. He wasn’t about to tip the captain to what he was working on. If he showed his hand, he might lose the game. Mazo usually gave Dorgo a free rein and let him play things his own way; it didn’t matter whether he knew the Dowser was lying or not. That’s the way it worked between them . . . and it often worked out quite well, too.

“I thought you knew every hooligan and harridan in Valdar?” Mazo asked.

“You think too highly of me, Cham.”

“Well, it looks to me as if he might have been an associate of Deto’s. The way they were both killed, that possibly ties them together. He probably crossed some very bad people and made them very, very angry. The crushed skull is a nice touch though, wouldn’t you say?”

“I’d say that this is definitely a revenge killing.”

“Remember, Dowser—you’re still on my payroll. I want this thing wrapped neatly and tied with a bow. These men may not have been models of virtue, but they were killed in my city. If their murders aren’t connected, than I’m close kin to a muledog.”

“My thoughts, exactly.”

“If I didn’t know you better, I might take that as an insult. But I’ll take it as proof that your brain is working. Now what about your eyes and ears? I want to know everything you see, everything you hear. Even what you smell. Make sure you don’t miss a trick.”

“Sounds like you don’t trust me.”

“About as far as you trust me.” Mazo grinned. “But I’ll give you plenty of rope. Try not to hang yourself with it.”

8: The Man from Salukadia

It was shortly before sunfall, and night’s shadows were already creeping up on the Knuckleback Hills and the Blunker house. It was rather cool for a summer’s night, especially so late in the month of Juvai. A soft breeze blew in from the north, carrying with it the smell of the sea.

The Blunker boys had settled down for a quiet evening at home. Urlak was reading a novel by Divad Mithos, the mad playwright, though he could never grasp the author’s subtle use of metaphor. Ollo sat at the table, struggling with a puzzle a child could have solved in an hour.

Seeing that it was growing dark, Urlak lit a pair of lamps. “Do you have any idea where Klor might be?” he asked his brother. “Haven’t seen him since he went into Valdar yesterday.”

Ollo looked up from the puzzle, scratched his buttocks, and then farted. “No, Urlak. Is he supposed to be here tonight?”

“Of course he’s supposed to be here tonight, you buffoon! We’re expecting Dowser and that friend of his. We’re selling the girl, remember?”

“Oh, yes. I forgot.” Ollo smelled the hand he’d used to scratch his rear end. “Why can’t we keep her? She’s pretty, and she smells good, too.”

“That’s it! Enough!” Urlak shook his head in frustration. “Either we sell the wench or I open her pretty little throat.” He tossed the book to the floor, jumped to his feet, and pulled a dagger from inside his shirt. “Your call. What’ll it be?”

Ollo leapt to his feet, knocking over the table and spilling the puzzle on the floor. “No! No more killing, Urlak. It’s bad luck, I tell you. You made me kill that poor witch and—”

“That poor witch would have cursed us with a nasty spell if we’d let her live after robbing her. And that would have been some real bad luck.”

Ollo paused to consider his brother’s words. “I guess you’re right.”

“Damn right I’m right. What would you ever do without me to do your thinking for you?”

“Don’t know. I never thought about it.”

The front door shook and rattled under a solid pounding.

“Who’s that?” Ollo asked.

“How the bloody Hell should I know?” Urlak stomped over to the door and opened it, dagger still clutched in his fist. “Who the devil are you?” he demanded of his visitor.

The stranger wore a black robe and a red skullcap. His hair hung in braids to his shoulders. He had dark skin and a beard that fell to his waist.

With a nod, the stranger bowed in a courtly manner.

“I am being here to talk business with one Urlak Blunker, goodly sirrah.” He spoke with a lilting, sing-song accent.

Urlak seized the man by the front of his robe and set the dagger against his throat. “How do you know my name? Who sent you?”

“I am most humbly, one Gonj Vedun of Salukadia. I am being sent here by that most illustrious of gentlemen, Dorgo Mikawber.”

“Is that so? Where is he? He’s supposed to be here.”

“I am regretting to say that Master Mikawber will not be joining us. He is asking me to be informing you that he is meeting with personages of great wealth who shall be buying very soon some very special jewels from your most excellent self.”

“Why didn’t you say all that in the first place?” Urlak grinned and looked the man over. “Say, haven’t I seen you around Valdar?”

“Have you ever been to knowing to be frequenting an establishment so named the Satin Cat?” Gonj Vedun asked.

“Yes, yes. That’s it.” Urlak didn’t want to look foolish by letting his visitor know that he was familiar with that bordello by name and reputation only.”

“Now please, most honorable sirrah, the presence of your weapon is causing me to a very big nervousness. I am begging you to be putting it away, for if you intend to be doing me hurt, then kindly be looking outside.”

As Vedun stepped aside and whistled, Urlak looked past him and frowned.

There, in the front yard, stood a large, black carriage; the driver holding the horses’ reins was a small figure wearing a hooded robe. Two huge figures stood at attention on either side of the carriage; they wore full suits of ancient armor, with great horned helmets that resembled the heads of dragons. Massive broadswords hung from their hips.

Urlak swallowed the lump in his throat in one loud gulp. “You’re much smarter than you look,” he said to Vedun.

“And you, my goodly man, judging by your most beautiless physiognomy, do appear to be exceedingly more cognizant than you truly are,” Vedun replied.

“That’s… uh, oh — right you are!” Urlak stammered. “And don’t you ever forget that, either.” He tossed the dagger onto a table in one corner, then stepped back and bumped into Ollo.

“Look, Urlak. Giants!”

Urlak pushed his brother out of his way. “Don’t stand there gawking like an imbecile! Fetch the girl — and make sure she’s bound and gagged real tight.” He nodded to Vedun. “Come in.”

The man from Salukadia entered the house as Ollo headed out through the back door. Urlak glanced back at the two giants and left the front door open.

“This sultan of yours must be a very rich man,” he said.

“He is wealthy beyond even the grandiose dreamings of wealthy men,” Gonj Vedun told him. “He is being most powerful sultan of all sultans.”

“Nice,” Urlak said.

Ollo returned a moment later, carrying their captive over a shoulder. He set her gently on her feet but did not remove her gag or her bonds.

Vedun approached her. “If you do promise not to be biting and shouting, I will take to be removing your gag,” he said.

The woman looked at him, showing no fear. She nodded, and Vedun removed her gag. He looked her over, walking a slow circle around her.

“How are you called, girl?” he asked.

“Elema. Elema Jorn,” she said. “Who are you?”

“Vedun. Gonj Vedun. From Salukadia.”

Elema’s eyes went wide with amazement.

Ollo nudged his brother. “Where’s Salukadia?”

“Do I look like a cartographer?” said Urlak.

“What’s that?”

“A mapmaker, stupid. Now shut up and be quiet!”

Gonj Vedun continued to inspect Elema. But he never touched her.

“Aren’t you going to look at her teeth?” Urlak asked.

The Salukadian glanced at Urlak, and shrugged. He turned to Elema. “Let me be seeing your teeth,” he said. She opened her mouth and he examined her teeth.

“Well? What do you think?” Urlak asked.

“Her teeth are in most excellent condition, very strong and very sharp, you see. She is being somewhat most skinny for my personal taste, but the sultan is liking his women in such a way,” Vedun said. “If you will be going outside, my men will be giving to you the five thousand in golden crowns that you have requested in exchange for this young woman.”

“You heard the man, Ollo,” Urlak said. “Go get it.”

Keeping quiet as he had been told, Ollo went outside. A few moments later he dragged a large wooden chest into the room, and Urlak flung open the lid. Inside, a mountain of gold coins glittered like the gates of Heaven. Urlak knelt and shoved his hands into the chest, feeling the coins, weighing them, grabbing handfuls and letting them slip through his fingers. When he was done, he stood and smiled at his brother.

“Are you not bothering to count?” Gonj Vedun asked.

Urlak barked a laugh. “There’s more gold in that chest than I’ve seen in my entire life,” he said. “Dorgo claims you’re an honest man. If we’re short a few crowns, I won’t lose sleep over it.”

Gonj Vedun bowed. “Then the girl and I shall be taking our leaving. It has been very most pleasurable, giving you the business.”

With a smile and a bow, he took Elema by the arm, and they left.

Slamming the front door shut, Urlak howled with glee. “We’re rich, little brother! Now we can buy that pig farm in Londoria.”

“But I wanted rabbits, Urlak. What about the rabbits?”

“We’ll be able to buy those, too, you lunkhead.”

Ollo grinned and clapped his hands. “Too bad Klor missed all the fun,” he said. Then he dropped to his knees in front of the chest and began washing his face with gold coins.

“To Hell with Klor!” Urlak knelt beside his brother and buried his head in the chest of gold.

9: Something About Moonstones

Dorgo sat in front of the mirror at Marlia’s vanity table. He removed the skullcap and wig, and then peeled off the beard. “That was too easy,” he said. “I worry when things are too easy.”

“Don’t be so superstitious,” Heegy told him.

Dressed in their ancient suits of armor, helmets tucked under their arms, two huge minotaurs stood in the doorway as if they were soldiers standing at attention.

“Thank you, Torok. Thank you, Shem,” said Elema, clasping hands with each brother in turn. “You’ll be well rewarded for your help.”

“Brother and me want no reward. We most happy to help,” said Torok the Terrible. “We go now. Be safe, friends.”

The minotaurs bowed, turned, and marched away like gladiators entering the arena.

Elema closed the door to Marlia’s office. “It’s not that I’m ungrateful . . . but five thousand crowns? Is that all I’m worth?”

“In today’s economy, that’s a fair price for a skinny little wench like you,” Heegy said with a laugh. He leaned against the wall, rubbing his lobeless ear and mooning over Elema.

“So who came up with a name like Gonj Vedun?” Marlia asked. She was sitting at her desk, pouring herself a cup of tea.

“Ask Elema,” Dorgo said, wiping off the dark greasepaint that hid the scar on his cheek.

“It’s the name of a character in an obscure little play called Deathwind of Akkad,” Elema said. “The only play Heegy ever wrote.”

Marlia shrugged. “Never heard of it.”

“She told you it was obscure,” the Big Dwarf said.

Dorgo finished removing his disguise and then turned from the mirror to face Elema. “I think it’s time you told us about Deto and the moonstones.”

Elema sat down on a divan. Heegy walked over to Marlia’s desk, poured a cup of tea from her pot, and handed it to Elema. She smiled at him, and then turned to Marlia.

“Don’t you have anything stronger?” she asked. When Marlia shook her head, Elema sipped her tea and told her story. “Deto and the Blunkers are old friends. I didn’t know those two dog humpers until they caught me trying to rob them. Anyway, Deto tipped them to this woman in Khanya-Toth who trafficked in moonstones. He said she’d sell them a pair at a fair price.”

“So the Blunkers went to Khanya-Toth and Deto told you what they were up to,” Dorgo said. “Do you know this woman?”

Elema shook her head. “All I know is, she and Deto were lovers, a few years ago. Her name was Zomandra Chuvai. She was some sort of witch.”

Something went click in Dorgo’s brain. “One of the Kha Jitah?”

“Why, yes. How did you know?”

“Just a hunch.”

“I’d hate to cross paths with one of them on a dark night,” Heegy said.

“So would I, Weasel,” Dorgo said. “So would I.” He patted the pocket where he kept the silver pendant he’d found clutched in the cold, dead fingers of Klor Lugo.

“Deto and I parted company shortly before the Blunkers returned from Khanya-Toth,” Elema said. “I don’t know where he got off to, and I don’t care. It was all over between us for good this time. He isn’t a very nice man.”

Dorgo let the comment slide; he wasn’t interested in Elema’s love life. “So you decided to steal the moonstones from the Blunkers, once they returned from Khanya-Toth?”

“Yes. At night, while they slept. But I bungled the job. Their place is a mess and I tripped over a stool. Urlak woke up and caught me. He wanted to kill me. Ollo wanted me for his pet. They kept me locked in a cave beneath their house.”

Giving her a long, hard look, Dorgo said, “Deto’s dead, Elema. So is another rogue by the name of Klor Lugo. He ran with the Blunker boys.”

It took a moment for Elema to absorb this news. Dorgo watched her face, tried to study her emotions. She was a cool one, he knew. Other than the look of surprise, the news didn’t seem to bother her all that much. After her comment about Deto Lepyr, he didn’t think it would.

“You think I snuffed them both?” she asked.

Dorgo shook his head. “You were a guest of the Blunkers on the nights they were killed.”

“Then who did them in?” Heegy asked. “The Blunkers?”

“No,” Dorgo said. “But I think they’re responsible, in some way.” He wagged a finger at Elema. “Something bad happened, girl. I think it happened in Khanya-Toth. And I think you know how it happened. You spoke of this Zomandra Chuvai in the past tense. Why did you do that?”

Tasting her tea, Elema turned to Marlia. “I know you don’t indulge, dear. But you really should keep something stronger on hand for your guests.”

“Next time,” Marlia promised.

Elema set her cup down and looked directly at Dorgo. “I heard the Blunkers talking about it. They never intended to buy the moonstones. They went to Khanya-Toth to steal them. Urlak, Ollo, and Klor. They robbed Zomandra. But first they murdered her.”

The ominous words of Jeke Teuqaj came back to haunt Dorgo: What is spawned in the shadows of Khanya-Toth lives only in the night ever after. He had a fairly good idea what had crawled out of that shadowy region, bent on revenge. But he kept that to himself, for now. Instead, he told the others what he knew about the origins of the moonstones, about the Otherworld of Sor Lunarum, the demonic Vah Lunari, and what they demanded in return for their act of self-castration.

“That must have hurt like all bloody Hell,” Heegy said, his face white.

“Don’t be silly,” Dorgo told him. “We’re talking about demons here. For all we know, they can grow another pair as easily as you and I grow new fingernails.”

“This is just all too much,” Marlia said. “Demonic testicles? Really.”

“It’s true,” Elema said. “Deto told me.”

“Why would anyone trade a piece of themselves in exchange for a pair of some demon’s chestnuts?” Heegy wanted to know.

Dorgo looked at Elema. “Did Deto tell you what price Zomandra paid?”

“It cost her one of her eyes.”

“Then why would she sell them? No amount of gold can replace the loss of an eye. There must be something about these moonstones we don’t know.”

“What Zomandra was selling were copies of the moonstones, not the originals,” Elema said.

“Copies?” Heegy said. “You mean fake moonstones?”

“Exactly. You see, when the original moonstones, the Lunari’s actual testicles, are exposed to the light of a full moon, they reproduce. Each moonstone makes a copy of itself once every full moon, for nine moths.”

“It’s like they’re making babies,” Heegy said, smiling at Elema.

Dorgo and Marlia exchanged glances. He rolled his eyes. She feigned having to vomit. Elema seemed oblivious to the Big Dwarf’s adoration.

“Can anyone tell they’re fakes?” Marlia asked.

“No, that’s the beauty of it,” Elema said. “But the copies do not multiply.”

“The Blunkers knew that, of course,” Dorgo said. “That’s why they killed Zomandra.”

“Let’s see,” Marlia said, using her abacus. “That’s eighteen copies of moonstones at ten thousand crowns a pair —”

“Ninety thousand crowns for Urlak and Ollo to share,” Elema said, staring at her.

“That’s a mighty big hill of beans,” Heegy said.

“What happens to the original moonstones afterward?” Dorgo asked.

“Nothing,” Elema replied. “They just never reproduce again.”

“If you sell those, then that’s another ten thousand crowns,” Marlia said.

A moment of dead silence descended upon the room. Only the rats could be heard, scurrying about inside the walls of the theater.

“Tell me, Dorgo,” Elema said, resurrecting the moment. “Who did you think would shell out some pretty serious coin for a pair of moonstones?”

Dorgo sighed. “I was counting on Gonj Vedun and that pirate treasure,” he said. “But they’ve both been written out of this play.”

“Don’t steal my lines, Mikawber,” Marlia said with a grin.

“Is anybody thinking what I’m thinking?” Elema asked.

The Big Dwarf smiled hopefully. “What are you thinking, my little crumpet?”

“Not what you’re thinking, that’s for sure,” Elema told him. “I think we should pay a call on the Blunkers and relieve them of the real moonstones.”

Dorgo’s left eyebrow curled upward. “Tonight?”

“Do you have a plan?” Marlia asked. “Or do we just storm the castle?”

“There’s a tunnel in the hills that leads to the cave where those pig pokers kept me chained,” said Elema. “I can slip in the back while the rest of you keep them busy out front. Who wants in?”

Heegy shrugged. “I guess I’m game.”

“You know I’ll play along,” Marlia said.

“What about you, Dorgo?” Elema asked.

Dorgo didn’t even have to think about it. “Urlak stuck a blade under my chin. Twice.”

Elema winked at Marlia. “Looks like we’re all going out for the night.”

Marlia stood up. “I’m sure you’d like to wash up and change into some clean clothes before we do this thing,” she told Elema.

“I would. Thanks.”

Heegy’s face lit up when Elema patted his cheek in passing as she followed Marlia from the room. Dorgo just shook his head.

“You know, the Blunkers are in for another surprise when they try to spend that fool’s gold,” Heegy said when he and Dorgo were alone.

“I know,” Dorgo said. “But I don’t think they’ll ever get the chance.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out the silver pendant. “This is the sigil of the Kha Jitah.”

The Big Dwarf’s eyes bulged. “Where did you get that?”

“Klor Lugo had it in his hand when I examined his body. I’m quite certain it belonged to that witch, Zomandra Chuvai.”

“He probably took it off her corpse.”

“I don’t think so, Weasel.”

“But—Elema said that Klor and the Blunkers killed her.”

“Maybe they didn’t kill her enough.”

10: Under A Gibbous Moon

Midnight but a few hours away, Dorgo and his three cohorts rode quietly through the Knuckleback Hills toward the cottage of Urlak and Ollo Blunker. A gibbous moon floated in a sky as black as sin and sprinkled with starlight.

Elema reined in her horse and called a halt. The others drew up alongside her. Dorgo and Marlia were mounted on the other two horses; the Big Dwarf rode the pony. They were all armed: Dorgo with his saber, Elema with a carving knife, Heegy with his rapier, and Marlia with a pair of handbows dangling from her saddle horn.

“This is where I leave you,” Elema said. “Stick to the plan and—good luck!”

Leaping down from her horse, she tossed the reins to Marlia and took off into the night. Marlia tied the extra reins to her saddle horn and nodded to Dorgo. Quietly, he led the way.

Lamplight shone in the windows of the cottage when they reached the stony front yard with the lonesome cactus. Dismounting quietly, Dorgo tethered his horse to the tree and walked up to the house. Heegy slid from his pony and tethered it next to Dorgo’s mount. Marlia stayed in her saddle and reached for one of the handbows.

Dorgo knocked soundly on the cottage door.

A few heartbeats later, the door flew open. Urlak stood there, looking surprised.

“Dowser!” he said. Then he noticed Heegy and Marlia. “And you’ve brought along the Dwarf and that clamlicker who thinks she’s a man —”

Something whooshed in the air — and a bolt from a handbow buried itself in the door frame, right next to Urlak’s head.

“More man than you’ll ever be, you swish,” Marlia told Urlak.

“What the hell’s going on here, Dowser?” Urlak demanded.

“So you thought to pull a twist and dodge,” Dorgo said. He grabbed Urlak by his shirt and threw him to the ground. “Call your brother out here. Tell him to bring the moonstones.”

“But I told you, Dowser. I won’t sell until after the full moon.”

“We’re not here to buy them. Now call your brother!”

Urlak caught the angry look in Dorgo’s eyes, saw Heegy draw his rapier, and saw Marlia pointing the handbow at him; it still held a second bolt. He did not get up.

“Ollo!” he yelled. “Ollo! Get the —”

Elema suddenly pushed Ollo through the open door. She had one arm wrapped around his neck. Her free hand held the knife to his throat. His eyes bulged in fear. He sweated and sputtered.

“Dowser!” Ollo cried. Then his eyes lit up as it all hit him. “You—you were that man from Salukadia. You’re that — that Vedun person!”

“I’m impressed, Ollo,” Dorgo said. “You actually figured that out without your brother’s help. By the way, boys — that chest of gold? It’s not real gold.”

“What the devil?” Urlak growled. “You played us!” He tried to get up.

Dorgo shoved him back down with his boot. “Where are the moonstones?”

“I’d rather die than give them up to the likes of you.”

“You ain’t that brave.” Dorgo turned to Elema. “What about the genius there?”

“Ollo says he doesn’t know where Urlak stashed them,” she said. “But I think he’s lying. He knows. Don’t you, Ollo?”

“Honest, I don’t,” he said. “I swear on Mother Blunker!”

“Maybe this will inspire you to start telling the truth.” Elema said, and then she bit down on the lobe of his right ear.

Ollo screamed insanely as Elema chewed and gnawed, then ripped the earlobe free. She let go of him and he collapsed, crying and clutching at his damaged and bleeding ear.

“Urlak! Look what she done to me!” he cried.

“That’s heartless, girl. Oh, that’s cruel,” Urlak said, slowly rising to his knees.

Elema walked over to Urlak and spat Ollo’s earlobe in his face. “Shut up, you catamite. This is for wanting to kill me.” She punched Urlak on the jaw. “And this is for trying to sell me into slavery.” She kicked him square in the testicles. He shrieked, toppled over and vomited. “Let’s see you grow a new pair of those by moonlight!”

She was about to kick Urlak again, but Dorgo stopped her.

“Enough,” he said. “Ollo, stop crying. Where are the moonstones?”

“Urlak’s pocket,” he said, holding a dirty kerchief to his ruined ear.

Elema stuck the knife in her belt and searched Urlak’s pockets until she found the red velvet bag. Quick inspection proved that it contained the moonstones. Tying the bag to her belt, she walked over to Marlia, who handed back the reins to her horse, as well as the spare handbow.

Dorgo watched in amazement as Elema mounted her horse and then pointed the small but deadly crossbow at Heegy.

“Toss the rapier aside, love,” she told the Big Dwarf. “Then give me the reins to your mounts, if you would be so kind.”

Dorgo sneered at Heegy. “So I’m too superstitious, am I?”

Heegy stood there, mouth hanging open.

“Sorry, boys,” Elema said. “This party is just for us girls.”