Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, and The Fantastic Four

There are two different stories about how it began.

There are two different stories about how it began.

In one story, there’s a writer-editor of boys’ adventure comics, who’s told by his boss — also his uncle — to create a new team of superheroes, a knock-off of the competition’s high-selling Justice League of America title. This isn’t what the writer really wants to do. But he talks it over with his wife. And he decides: I’m going to write the book the way I want to, without worrying about making perfect heroes. Maybe one of the leads will actually be a monster. Maybe another’ll be a teenager, the kind of character who in other books would just be a sidekick. They’ll bicker among themselves, and fight. They’ll be real people. And, in this story, that’s what the writer did; and it worked.

The other story has a veteran comics artist coming in to the studio of the second-rate company he’s working for. He finds the young writer-editor of the comics line crying because they’re moving the furniture out; the company’s about to close down. No problem, says the artist; you tell your uncle, the owner, to hold off folding the business. The artist, a veteran storyteller, knows how to make grab an audience. He starts cranking out the books, new title after new title. Superheroes are back in, so he starts doing superheroes like nobody ever did them, throwing everything he sees around him into his stories, everything he reads in newspapers and magazines, everything he ever found in history books and myths. Scientists. Mutants. Gods and monsters. In this story, that’s what the artist did; and it worked.

Human memory is fallible, especially when, as in this case, the two people closest to the case become estranged. What can be said for sure is this: starting in 1961, Marvel Comics, a formerly undistinguished publisher, began producing a wave of brilliant superhero comics. Most of them were written by Stan Lee, and most of the best were drawn by artist Jack Kirby — with another artist, Steve Ditko, producing two other remarkable books with Lee’s involvement. Of all the Kirby-Lee collaborations, perhaps the best was the original flagship book of the Marvel line, the first title that came in many ways to define Marvel Comics as a whole: The Fantastic Four.

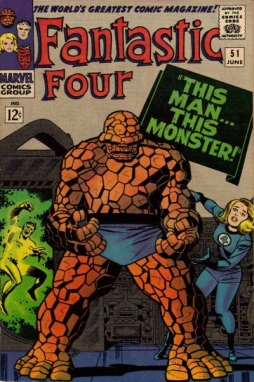

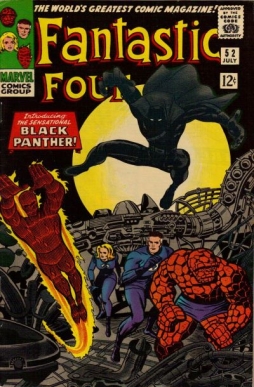

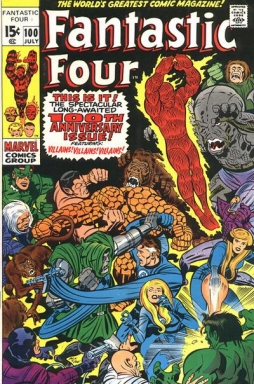

The two men produced 102 issues of that title together, plus a few giant-sized annuals (and another issue half-drawn by Kirby, heavily re-conceived by Lee and completed by another artist, John Buscema). That’s an incredible record of longevity; few runs of North American comics have gone on so long. Kirby’s productivity was herculean. The typical comics artist today has difficulty doing one 22-page book a month. Kirby routinely wrote and drew seventy-five pages a month at Marvel. And yet rather than fall back into repetition his stories exploded with new ideas, new concepts, new characters and new approaches to character. Fantastic Four was perhaps his best book, the home to many of his best ideas; omnipotent cosmic gods, truly alien races, the single greatest villain ever to appear in superhero comics.

The two men produced 102 issues of that title together, plus a few giant-sized annuals (and another issue half-drawn by Kirby, heavily re-conceived by Lee and completed by another artist, John Buscema). That’s an incredible record of longevity; few runs of North American comics have gone on so long. Kirby’s productivity was herculean. The typical comics artist today has difficulty doing one 22-page book a month. Kirby routinely wrote and drew seventy-five pages a month at Marvel. And yet rather than fall back into repetition his stories exploded with new ideas, new concepts, new characters and new approaches to character. Fantastic Four was perhaps his best book, the home to many of his best ideas; omnipotent cosmic gods, truly alien races, the single greatest villain ever to appear in superhero comics.

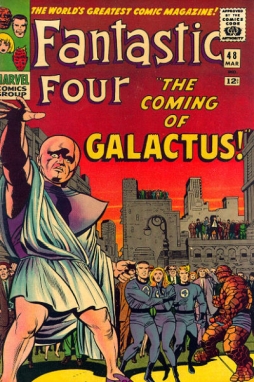

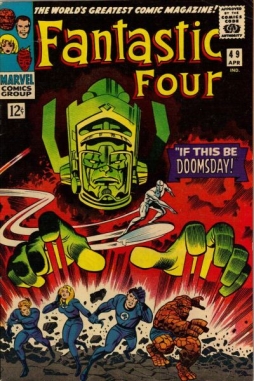

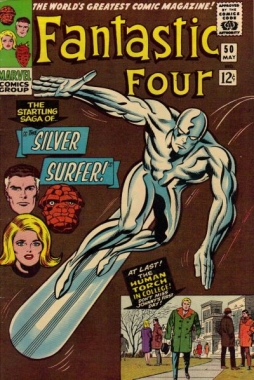

Wait, though, you may be saying. Wasn’t Lee the writer on the book? Well, yes, but. Conflicting memories again make things unsure. What can be said is this: with most of his artists, and particularly with Kirby, Lee would typically have a story conference, possibly over the phone, and based on the conference might then type up a synopsis. The artist would draw the book based on the conference and synopsis, and Lee would write dialogue and captions based on the completed art. Which meant the artist got to determine the length of scenes, got to decide how to lay out a page to emphasise certain moments — got to determine a story’s pace and structure. But more than that: it has been asserted, especially by Kirby, that the story discussions with Lee were often perfunctory, and might only have consisted of the artist telling Lee how the story would go. Notes on Kirby’s original art boards seem to outline plot points and suggest dialogue. There’s a rumour I’ve heard that Lee’s plot suggestion for one of the most famous FF stories of all consisted of telling Kirby “Have them fight God.” Kirby supposedly then took that four-word phrase and turned it into a three-issue saga (FF 48-50, the original Galactus trilogy), perhaps one of the greatest tales in the history of Marvel Comics.

It is possible that Lee’s contribution was significant. Certainly he provided the final script for the book, and created a specific tone that became characteristic of Marvel — breathless adventure along with rueful self-aware irony, bombast and humour and melodrama mixed together. He probably defined the voices of the main characters of the book, a quartet of adventurers who, mutated by cosmic rays during an illicit spaceflight, become super-powered adventurers.

You can find some interesting themes in the book, and at this point it’s impossible to be sure if they were conscious creations of Lee, or Kirby, or whether either were aware of them. One of the characteristics of the Fantastic Four is that they’re not just a team; they’re a family. Reed Richards, the super-stretchable Mister Fantastic, woos and marries Sue Storm, the Invisible Girl, during the course of the Lee/Kirby run. Sue’s brother Johnny, the Human Torch, has a complex interaction with Ben Grimm, the super-strong but monstrous-looking Thing; as the book goes on, the relationship goes from combative to avuncular, even as Ben becomes more and more of a character, an identifiable, relateable person — one often said to be based on Kirby himself. I don’t know how much of these family matters were intended by Kirby, how much by Lee, and how much they came out of the natural situation of the characters.

You can find some interesting themes in the book, and at this point it’s impossible to be sure if they were conscious creations of Lee, or Kirby, or whether either were aware of them. One of the characteristics of the Fantastic Four is that they’re not just a team; they’re a family. Reed Richards, the super-stretchable Mister Fantastic, woos and marries Sue Storm, the Invisible Girl, during the course of the Lee/Kirby run. Sue’s brother Johnny, the Human Torch, has a complex interaction with Ben Grimm, the super-strong but monstrous-looking Thing; as the book goes on, the relationship goes from combative to avuncular, even as Ben becomes more and more of a character, an identifiable, relateable person — one often said to be based on Kirby himself. I don’t know how much of these family matters were intended by Kirby, how much by Lee, and how much they came out of the natural situation of the characters.

Similarly, from a 21st-century viewpoint it’s hard to miss the fact that the book seems concerned with masculinity, and what it means to be a man. Given that it was aimed at boys, that’s not surprising; it’s a book about how you grow up, how you become a hero. Reed, Ben, and Johnny all seem to be at different stages of life — Reed and Ben were supposed to be at college together, but to me Reed seems an older man, the patriarch of the group. Sue’s less defined than any of them; like Ben’s girlfriend, the blind sculptress Alicia, she never really develops an identifiable voice of her own. In fact, she often seems sidelined from the group. It has been argued that to some extent this comes from Lee’s scripting; that if you read the book strictly looking at Kirby’s art, ignoring the dialogue and captions, Sue becomes more of a central figure in the group.

Personally, I think the book is more Kirby’s than Lee’s. I think that the things that make the book work are things that Kirby brought. It’s impossible to be sure, at this point, given the fallibility of memory and competing stories. But when I look at the book, what draws me in is the visual storytelling, the design sense, the feel of strong-willed characters clashing, the vistas of unknown dimensions and faraway planets: all Kirby’s strengths.

Kirby’s art is perhaps literally peerless. It’s a commonplace that he was able to express power and stylised violence like nobody else; and that his storytelling was incredibly fluid. Re-reading the books I was struck as well by his ability to create three-dimensional spaces, his sense of perspective, and how he knew when to draw a detailed background and when to let the background drop away to let a panel ‘read’ faster. Above all, going through his entire FF run, you’re stunned by the sheer consistency of his dynamic compositons, the explosive energy in panel after panel, page after page, issue after issue. There’s an intuitive assurance to his art, the sure and easy knowledge that he can do whatever he wants in a panel and make it sing.

Kirby’s art is perhaps literally peerless. It’s a commonplace that he was able to express power and stylised violence like nobody else; and that his storytelling was incredibly fluid. Re-reading the books I was struck as well by his ability to create three-dimensional spaces, his sense of perspective, and how he knew when to draw a detailed background and when to let the background drop away to let a panel ‘read’ faster. Above all, going through his entire FF run, you’re stunned by the sheer consistency of his dynamic compositons, the explosive energy in panel after panel, page after page, issue after issue. There’s an intuitive assurance to his art, the sure and easy knowledge that he can do whatever he wants in a panel and make it sing.

Along with that goes an incredible knack for design. Kirby’s experiments with collage as a way of depicting alternate dimensions or interstellar space are notorious, but to me more remarkable is his ability to design machinery, spacecraft, aliens — all unique, all filled with personality. And his character designs are stunning, catching in Kirby’s personal idiom the essence of who the character is. It’s not just that Kirby (and Lee) were consistently able to come up with new and dynamic opponents for the Fantastic Four, with characters and concepts setting off the main stars of the book; it’s that they all had their own dynamic looks.

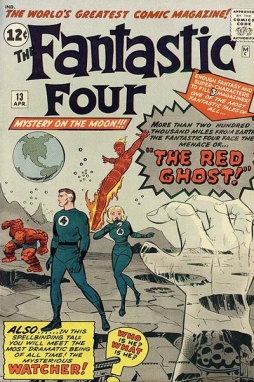

(Here’s an interesting exercise: compare the number of original lasting characters from the Kirby run on FF with the number of lasting characters to come out of the book since. By ‘lasting’ let’s say, oh, characters who return in two separate stories after the one that introducses them. The first hundred issues of the series saw, among others, the FF themselves, Doctor Doom, The Mole Man, the Skrulls and later the Super-Skrull, the Puppet Master and his daughter Alicia, the Impossible Man, the Red Ghost and his Super-Apes, the Watcher, the Mad Thinker and his Awesome Android, Rama-Tut, the Molecule Man, the Hate-Monger, Nick Fury as a modern-day secret agent, Diablo, Attuma, Dragon Man, the Wingless Wizard, the Inhumans, the Silver Surfer, Galactus, the Black Panther, Klaw, Blastaar, Annihilus, Franklin Richards … the list just goes on and on. In the post-Kirby years we get Thundra, Herbie the robot — who came from a cartoon in which Kirby had a hand — the Texas Twister, Captain Ultra, Frankie Raye, Terminus … plua a lot of characters deriving from the Kirby run. There’s Kristoff, Doctor Doom’s back-up copy; Nick Scratch and Salem’s Seven; Air-Walker, Firelord, and Terrax the Tamer, all heralds of Galactus; Nathaniel Richards; maybe some of the Fantastic Force characters; various Skrulls and Inhumans turn up; Valeria Richards is born. On the whole I wouldn’t be at all surprised if more lasting creations were introduced in the first 100 FF issues than in the 500-plus issues since.)

The Fantastic Four as a group are a great visual. They have a uniform — like Kirby’s earlier non-super-powered team of explorers the Challengers of the Unknown — but that’s only the starting point. There’s a man in the blue uniform, whose body is often distorted by the use of his powers; a woman in the blue uniform, often turned invisible and indicated only by dotted line; an orange monster; and a red-and-yellow flaming teen. So right away there’s a strong colour contrast among the team. And a strong contrast in shapes — each of their powers is intensely visual, even, paradoxically, the Invisible Girl’s, and so the uniform and ‘4’ icon gives just enough of a link to tie them together. (You could say, I think, that Kirby did something similar with his designs for the X-Men; again, a uniform, and again, each character wore it a little differently — one with a visor hiding his eyes, one with wings, one all-over ice, and so forth.)

The Fantastic Four as a group are a great visual. They have a uniform — like Kirby’s earlier non-super-powered team of explorers the Challengers of the Unknown — but that’s only the starting point. There’s a man in the blue uniform, whose body is often distorted by the use of his powers; a woman in the blue uniform, often turned invisible and indicated only by dotted line; an orange monster; and a red-and-yellow flaming teen. So right away there’s a strong colour contrast among the team. And a strong contrast in shapes — each of their powers is intensely visual, even, paradoxically, the Invisible Girl’s, and so the uniform and ‘4’ icon gives just enough of a link to tie them together. (You could say, I think, that Kirby did something similar with his designs for the X-Men; again, a uniform, and again, each character wore it a little differently — one with a visor hiding his eyes, one with wings, one all-over ice, and so forth.)

I’ll go a step further, and say that the designs were distinctively Kirby. I think the patterns of the Thing’s rocks are expressionistic in a way that’s wholly Kirby — as many talented artists as have drawn the character in the years since, I’m not sure I’ve found any that felt quite right. The geometrical lines and shadows that make up his craggy shape are Kirbyesque without drawing attention to themselves, cartoony and even abstract yet still intuitively right.

I think there’s something similar, although less extremely individual, in the way Kirby drew Reed’s stretching power; he made the super-elastic acts seem not natural but credible. I think that’s a function partly of Kirby’s incredible sense of panel design, and partly a function of his sense of body language. His characters are almost always coiled, tense, writhing, as though about to bust out of their flesh with sheer energy. Reed goes a step further, and actually does what the rest promise, his physical form stretching as though by the intensity of his will and emotion. That’s Kirby’s Reed; a man who isn’t bound by the limit of his own body. Kirby’s knack for creating powerful imagery through foreshortening and distortion makes Reed’s power (like Johnny’s flames, or Sue’s force fields) a design element, part of the visual signature of the book.

Worth pointing out at this point is the contribution of Kirby’s inkers. Chic Stone, for example, gave Kirby an almost Hergé-like clarity of line, a cartooniness that emphasised the flatness of forms. At its best, its memorably bold. Like a lot of people, though, I prefer Kirby’s later inker, Joe Sinnott, who brought a range of textures and a heightened realism. Sinnott emphasised the emotions of the characters, I feel, and managed the difficult trick of keeping the vivid distortions of Kirby’s style while also making the pictures seem concrete, giving the details and sense of weight of the real world.

Worth pointing out at this point is the contribution of Kirby’s inkers. Chic Stone, for example, gave Kirby an almost Hergé-like clarity of line, a cartooniness that emphasised the flatness of forms. At its best, its memorably bold. Like a lot of people, though, I prefer Kirby’s later inker, Joe Sinnott, who brought a range of textures and a heightened realism. Sinnott emphasised the emotions of the characters, I feel, and managed the difficult trick of keeping the vivid distortions of Kirby’s style while also making the pictures seem concrete, giving the details and sense of weight of the real world.

Still, realism is not the distinguishing mark of the book; these were wild pop sci-fi stories for kids. It’s often said that what distinguished Marvel from DC Comics was the realism of the former, but this isn’t true at all. Marvel succeeded, particularly in Fantastic Four, by being more cosmic. The emotional lives of characters who were still relatively two-dimensional were just enough to give a sense of scale to Kirby’s cosmic wonderment. The grounding in something vaguely recognisable as human foibles throws the wildness of gods from outer space into greater relief. (It’s actually tempting to see the claim that Marvel’s realism is the key to their success as an attempt to privilege Lee over Kirby.)

The characters in Fantastic Four certainly aren’t realistic in the sense of having fixed backstories and being a product of a given historical moment and culture. They are what they need to be: archetypes just broad enough to make the stories affecting. To get a sense of the limits how real they are, look at the question of the Invisible Girl’s age. In different stories, we’re told that she and Reed were kids together; that she was a minor when the Fantastic Four started as a group; and that Reed (along with Ben) fought in World War Two. These statements can’t all be true, and they really don’t need to be. Realism demands that characters have a fixed background in a certain time and place, that shapes or helps to shape who the characters are; the simpler, arguably more primal, type of story in The Fantastic Four only requires that characters have identifiable emotional tendencies and, perhaps, dialogue tics. Within that simplified approach to character, great things can be done.

Consider the single greatest villain in the history of super-hero comics, Doctor Doom. There’s nothing remotely realistic about Doom, the son of a Romany witch who takes over his own Mitteleuropean country. The equal of Reed Richards in intellect, he wears a cloak and suit of powered armour, hiding his face that was scarred after the failure of an experiment aimed at contacting his mother’s soul in Hell. A mixture of medieval and high-tech monstrosity, he’s the perfect mixture of Gothic villainy and ultramodern danger. Everything about him’s unreal, dreamlike, threatening, and, under Kirby, oddly convincing.

Consider the single greatest villain in the history of super-hero comics, Doctor Doom. There’s nothing remotely realistic about Doom, the son of a Romany witch who takes over his own Mitteleuropean country. The equal of Reed Richards in intellect, he wears a cloak and suit of powered armour, hiding his face that was scarred after the failure of an experiment aimed at contacting his mother’s soul in Hell. A mixture of medieval and high-tech monstrosity, he’s the perfect mixture of Gothic villainy and ultramodern danger. Everything about him’s unreal, dreamlike, threatening, and, under Kirby, oddly convincing.

I’ve always felt that super-hero stories were the daylight form of the Gothic; both of them stylised narratives mixing real-world settings and fantastic elements, all aimed at a heightened emotional intensity. Both dominated by strong-willed villains. Doom is the ultimate in that line; his first name, Victor, seems designed to recall Frankenstein. Look at his first appearance, in Fantastic Four #5, from the perspective of Sue Richards: the FF’s home, the Baxter Building, is covered in an electrified net thrown from a helicopter by the mysterious figure of Doom. Reed describes his background (a typically Gothic nested narrative structure). Doom insists on taking Sue hostage, then has the rest of the group come to his castle where he sends them back in time to gather a great treasure — which, though they don’t know it, will make him master of the world. Sue watches them go; she is left behind, trapped alone in the crumbling castle of Doctor Doom. We don’t follow her, though, but watch the other three acquire the items (Blackbeard’s treasure) and return. Doom then traps them in an airless room. Only Sue, risking Doom’s wrath, can short-circuit his machines and free the others. Seen from another perspective, then, this is a Gothic narrative; ancient castle, sinister villain, trapped heroine. But the way in which it’s told gives it a different genre colouring.

It’s an interesting point that however often Doom returns, however often he alone confronts the FF, we never feel that four against one is an unequal fight. The FF often encournter lone villains, in fact, beings of staggering power — Dragon Man, Psycho-Man, Annihilus, above all Galactus. Only their relatively uninteresting counterparts, the Frightful Four, are a recurring matching group; the FF battles the Royal Family of the Inhumans when they first appear, but after that the Inhumans become a part of their extended cast. I think this all plays into the book’s theme of family. Villains are loners. They don’t have family groups around them.

I think it’s also interesting that the book’s less manichean than Kirby’s later stories. It’s not really about the battle of good and evil. Later Kirby tales pitted New Genesis against Apokolips, the Eternals against the Deviants. That was less apparent in his Marvel work, though I suppose you can see traces of it in Thor, with the Asgardians battling the Frost Giants. Still, the point of FF is not to depict great battles. It is, in the words of another 60s phenomenon, to explore brave new worlds. The FF are explorers, not crime-fighters or warriors, and their world is unbounded even by morality; at the extreme, we find Galactus, who transcends right and wrong, heroism and villainy.

I think it’s also interesting that the book’s less manichean than Kirby’s later stories. It’s not really about the battle of good and evil. Later Kirby tales pitted New Genesis against Apokolips, the Eternals against the Deviants. That was less apparent in his Marvel work, though I suppose you can see traces of it in Thor, with the Asgardians battling the Frost Giants. Still, the point of FF is not to depict great battles. It is, in the words of another 60s phenomenon, to explore brave new worlds. The FF are explorers, not crime-fighters or warriors, and their world is unbounded even by morality; at the extreme, we find Galactus, who transcends right and wrong, heroism and villainy.

The book’s ever-expanding cast of characters, with recurring villains and supporting cast members, was accompanied by a growing roster of locations and concepts — the Baxter Building, the Negative Zone, the Blue Area of the Moon, sunken Atlantis, the Mole Man’s underground lair of Subterranea. As the book went on, the stories began to weave back and forth between these different elements and characters, at the same time as they added new ideas, or drew from other Marvel titles. The complexity grew, and stories sprawled beyond a single issue. Whole sagas opened easily into others. The title came to feel less like individual tales of a fixed group, and more like an ongoing story.

It was and is a strange, unquantifiable structure for a tale. But one that worked brilliantly. One idea, one set of characters, would contrast with another, or interact unexpectedly with some other idea. The Inhuman Triton turns out to be the only one who can save Reed Richards from the Negative Zone. Another Inhuman, Crystal, falls in love with Johnny and joins the FF. Perhaps most memorably, the angelic Silver Surfer has his cosmic power stolen by the diabolical Doctor Doom. The story grows to hold all these things.

Maybe the greatest single-issue example of what I mean, and perhaps the Platonic ideal of a Marvel comic, is FF Annual 3. It’s the wedding of Reed and Sue. Doctor Doom decides to take a hand, and builds a machine that drives all the villains of the Marvel Universe to attack the Fantastic Four at the wedding — which is being attended by every single hero in the Marvel Universe. What ensues is a wild, exuberant, nonstop fight scene, swinging ecstatically from character to character; it begins with Doctor Strange casting the Red Ghost and his apes into another dimension, and only builds from there. It’s the absolute purest example of what 60s Marvel did, what the books felt like, and what Jack Kirby could do.

Maybe the greatest single-issue example of what I mean, and perhaps the Platonic ideal of a Marvel comic, is FF Annual 3. It’s the wedding of Reed and Sue. Doctor Doom decides to take a hand, and builds a machine that drives all the villains of the Marvel Universe to attack the Fantastic Four at the wedding — which is being attended by every single hero in the Marvel Universe. What ensues is a wild, exuberant, nonstop fight scene, swinging ecstatically from character to character; it begins with Doctor Strange casting the Red Ghost and his apes into another dimension, and only builds from there. It’s the absolute purest example of what 60s Marvel did, what the books felt like, and what Jack Kirby could do.

Kirby understood story better than anyone; understood something that carried over into other, lesser Marvel books for years after he left. And that is this: people didn’t buy FF to get a story crafted according to the rules of Aristotle or Robert McKee or even Joseph Campbell. They buy the book to see super-heroes in action, to see wild fight scenes, to go strange places. To have their minds blown. The story is a scaffold, a delivery mechanism to get the important things across.

For all that Kirby’s famous for his depiction of action and violence, what I think makes his work stand out is its deep interaction with the feeling of awe. Obviously it depicts characters caught up in that feeling — as I say, enough realism to bring home the scale of events. What makes the appearance of Galactus stand out, perhaps more than anything, is the dazed Human Torch coming back from the interstellar god’s ship to collapse, muttering “I traveled through worlds … so big … so big … there … there aren’t words …! We’re like ants … just ants … ants!!” (I don’t know if those words were original to Lee, or suggested by Kirby.)

At heart, I feel that Kirby’s art is perhaps unmatched in comics in its ability to instill awe. He knows when to cut to a splash page or two-page spread, how to build to those moments by the rhythm of his panels. He knows how to depict moments of transfiguration — a human shape suggested with a few lines, overwhelmed by light and energy. There’s a sense in which the book could be said to be about transfiguration; the FF gaining their powers from cosmic energy, Doom as a failed attempt at similar ascendance. Things change. People change, and grow.

At heart, I feel that Kirby’s art is perhaps unmatched in comics in its ability to instill awe. He knows when to cut to a splash page or two-page spread, how to build to those moments by the rhythm of his panels. He knows how to depict moments of transfiguration — a human shape suggested with a few lines, overwhelmed by light and energy. There’s a sense in which the book could be said to be about transfiguration; the FF gaining their powers from cosmic energy, Doom as a failed attempt at similar ascendance. Things change. People change, and grow.

After Kirby left, I don’t think the book ever found anything like the same level of creative success. There’ve been fun runs, and well-crafted tales, but never that level of consistent ground-breaking excellence. There’s a possibly-apocryphal story that in the early 70s, after Kirby left, Stan Lee told his writers — for as Marvel had grown, other writers had joined the company — that the company would no longer be about change, but about the illusion of change. That wasn’t good in the long run for any of the books, I think, but it was a real problem for Fantastic Four. The Fantastic Four are supposed to be a family, and families naturally go through changes. Young people marry into other families; new children are born; older folk, sadly, pass away. If there’s one point that the Kirby FF makes about family it is this: a family is a way to experience and process change. Lacking that, the book couldn’t really be what it once was. It became just another Marvel comic: sometimes good, sometimes bad, often diverting, rarely involving.

There’s nothing wrong with that, I suppose, and at least the book has a great legacy behind it. Starting on the third issue of the book, Lee, inveterate huckster that he is, slapped the tag “The world’s greatest comic magazine!” on every FF cover. For as long as I can remember I’d always dismissed the line. Re-reading the books recently, though, I felt a kind of shock go through me when I realised that for a good stretch of time in the 1960s, that phrase on that book was no more or less than the literal truth: this really was the greatest comics magazine in the world. I don’t mean to dismiss Crumb or Tezuka or Hergé, who were all also doing great work in those years, but nothing I’ve read by any of these men reach the consistency and power of Kirby’s work.

Perhaps this is the final statement to make on Lee and Kirby together: it’s a testament to Lee that he could create not just unmatched hype around a book, but an air of expectation in the book itself, the sense of something earth-shattering about to happen. It’s a testament to Kirby that he could deliver on that promise. There was no boast Lee could make that Kirby couldn’t back up. Together they created the world’s greatest comic magazine. And from that book a whole universe sprang.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Terrific article about my all-time favorite comic run, Matthew. Several keen insights, but the one I value most was:

> The FF are explorers, not crime-fighters or warriors

Indeed. Well said, and when you view the team in that light (particularly their leader, Reed, who lead them into most of their adventures), it gives you more insight into how Kirby liked to hang his tales.

Not as selfless heroes out to right wrongs (as their contemporaries, Spider-man and Daredevil, to pick two non-Kirby books), but as brave explorers helpless in the face of their own curiosity and desire to explore. The constant sense of awe in the book always seemed to me to be the natural reward for that motivation, and what made the book the most adult Marvel title (at least to my pre-teen eyes).

Fantastic Four was the first title I seriously collected once I had the money to do so, and I still remember reading the early issues (starting in the late teens — best I could so on my student budget) all the way through to 100 or so. It was a marvelous journey.

That was a fantastic article. Kirby brought awe. Yes. I totally agree. I remember so well sitting on my cousin’s bed as a seven or eight year old boy. I read about Galactus then and was awed by the story. I knew then as a young boy that I would own tons of comics. Kirby awed me then and he continued to do so for years. He was the master. Thanks for your article!

Great article! I remember learning about The Fanatstic Four from a library book and was fascinated by the odd villains they fought. Never knew where to begin in reading back issues, but the mythos all its writers and artists created for characters like the Skrulls and Galactus is incredible.

AN interesting point about the Fantastic Four being primarily explorers, and one that I suspet was picked up by Warren Ellis who, when writing “Planetary” (one of the few comics post-90s that I love), recast the FF, in effect, as the ultimate villains – a riff on the fact that they would constantly discover or even invent fantastic new technologies during their adventures, none of which ever made the slightest change to the world beyond their tower headquarters.

“It’s often said that what distinguished Marvel from DC Comics was the realism of the former, but this isn’t true at all. Marvel succeeded, particularly in Fantastic Four, by being more cosmic.”

This is a really good point. There’s a lot of talk about the “realism” of the Marvel Universe, but if you really look at it a lot of that doesn’t go anywhere especially interesting. What made Marvel great was how in your face it was compared to DC, and the way it seemed to draw on and energize classic pulp sci-fi/fantasy tropes. The FF going bankrupt in that one issue was kind of cute, but it’s not like I ever wanted to read something like it again despite Stan Lee often citing “money troubles” as a great distinguishing trait of Marvel heroes.

[…] of the closeness of the super-hero story to the horror story and to the gothic (something I’ve mentioned before). One of the regions of Astro City is Shadow Hill, a neighbourhood dominated by immigrants […]

[…] brilliant young men who meet at university, one of them named Victor, can’t help but point to a famous super-hero precedent; the fact that the first flashback sequence begins with Victor obliterating the word ‘marvel’ […]

[…] I like a lot of adventure fiction quite a bit. I’ve written enough about Robert E. Howard, early Marvel comics, Jack Vance’s Dying Earth — I’ve even written about Fighting Fantasy gamebooks and a […]