Hal Duncan’s The Book of All Hours, or Vellum and Ink

Hal Duncan’s The Book of All Hours is a dazzling, fascinating, frustrating work. A duology consisting of 2005’s Vellum and 2007’s Ink, it plays with structure and story in powerful ways, while also seeming to fall back too easily into black-and-white absolutes and traditional forms. The oddity of the book is that although in some ways it appears radically new, in other ways, as one reads further into it, it comes to feel more and more familiar.

Hal Duncan’s The Book of All Hours is a dazzling, fascinating, frustrating work. A duology consisting of 2005’s Vellum and 2007’s Ink, it plays with structure and story in powerful ways, while also seeming to fall back too easily into black-and-white absolutes and traditional forms. The oddity of the book is that although in some ways it appears radically new, in other ways, as one reads further into it, it comes to feel more and more familiar.

The basic idea might have come from a Marvel comic book: hidden among mortal humans are individuals who, when they undergo certain traumas, develop great powers to shape the world — they become gods, angels, demons. Archetypes. Unkin. Their powers extend not only across time and space, but through the array of alternate worlds called the Vellum; and, as well, into worlds deeper and more profound than our own and its cognates.

A long time ago one of these Unkin created the Book of All Hours, which is, among other things, a map of the Vellum, and a text describing everything, defining everything, holding all stories and worlds within itself. Various Unkin factions want to get their hands on the Book, to rewrite it to suit themselves. The Covenant, a primal patriarchy ruled by archangels, represent one major faction. Another loose grouping is formed by seven individual Unkin, seven archetypes we trace through a range of alternate selves. These seven are (to use only one version of their various names, and a reductive description of their identities) Jack Flash, eternal rebel; Joey Pechorin, eternal traitor; Guy Fox, mastermind; Seamus Finnan, a tortured Prometheus; Don MacChuill, the old soldier; Phreedom Messenger, warrior queen; and her brother, Thomas Messenger, the eternal sacrifice.

The Book of All Hours is an odd mix of different narratives, organised into four parts tied to the four seasons, with each part having a different mythic text at its heart as a kind of anchor. It is frankly very difficult to keep track of what is actually happening in the overall narrative of Unkin struggling to gain or regain the book, struggling to unite or recognise each other. At the same time, though, I found that the book works because there are so many different narratives, contrasting and reflecting upon each other. The stories seem to act like waves, that flow in, recede, and then recur.

The Book of All Hours is an odd mix of different narratives, organised into four parts tied to the four seasons, with each part having a different mythic text at its heart as a kind of anchor. It is frankly very difficult to keep track of what is actually happening in the overall narrative of Unkin struggling to gain or regain the book, struggling to unite or recognise each other. At the same time, though, I found that the book works because there are so many different narratives, contrasting and reflecting upon each other. The stories seem to act like waves, that flow in, recede, and then recur.

Different stories dominate different parts of the book, but climaxes are rare. Stories are told and retold with subtle changes, seeming to mark a change in the overall narrative. The different tales have different registers, different genres; they sit oddly next to one another, but intentionally so. Duncan’s got a knack for style, for explosive imagery and rhythmic prose, and that helps to pull one through the sudden shifts of tone.

It seemed to me, overall, that though no one narrative was necessarily overlong, cumulatively the various iterations of story seemed to stretch the book out too much. The tales too often promised a revelation, a plot movement, without delivering. I frankly wonder whether some of them could not have been profitably collapsed into others, though at the same time I suspect this might require radical structural rethinking of the book (each of the four parts has seven chapters, with each chapter followed by a section called ‘errata;’ there are three different fonts, and innumerable sub-chapters). On the other hand, the book doesn’t feel over-determined in its form, but instead has a sense of sprawl, which might be good or might be bad or might be both by turns.

For me as a reader, the result of the often-compelling style and the diffuse structure — vigorous in terms of the individual units, slow to develop an overall effect — is that I focus on what is happening at any given time. I’m concentrating on the moment, the clarity of action right before me. The chunk of narrative (most of the stories are told in bits of a paragraph or two) becomes a puzzle-piece which I turn over looking for connections. It’s an interesting effect, but it does mean that I find it difficult to keep a sense of the whole book in my head at any given moment. Which may well be appropriate.

The effect of the movement from story to story is a kind of insistence on irony. Everything’s relative. Nothing’s as urgent as it seems, because there’s always another story, another iteration of this story, in another fold of the Vellum. The book urges the reader to take an infinite perspective. This ought to undercut the drama, and sometimes does; but at other times it opens up a peculiar sense of scope, a truly mythic sense of infinite variety.

The effect of the movement from story to story is a kind of insistence on irony. Everything’s relative. Nothing’s as urgent as it seems, because there’s always another story, another iteration of this story, in another fold of the Vellum. The book urges the reader to take an infinite perspective. This ought to undercut the drama, and sometimes does; but at other times it opens up a peculiar sense of scope, a truly mythic sense of infinite variety.

For all the book’s pyrotechnics, it still has the power, at least on occasion, to move and to emotionally convince. Scenes with Finnan in labour conflicts between the First and Second World Wars are strong. And Vellum in particular is haunted by references to the murder of Matthew Shepard. I found it gave the book a strong resonant heart — Duncan’s response to Shepard’s murder is a working of painful reality into art, which to me is one of the more noble effects writing can have. Duncan makes Shepard the incarnation of a myth, makes the sad details of mere fact a symbol of some greater story. I think that’s a profound and significant achievement, one of the best elements of either book.

Still, if Duncan does have the power to move a reader, I found the surface of The Book of All Hours was often a kind of nervous evasion of real moment. I don’t mean that Duncan has distracting stylistic tics (though I think he too often used ellipses to provide a … certain emphasis), so much as to say that the sheer amount of invention and idea seems to divert a reader from the matter that would be more immediately resonant. This is, I feel, on the whole a good problem to have; it suggests that the book has the depth to hold up to a re-reading — and that re-reading is necessary to fully grasp it, which seems also to follow from the complex structural techniques of the tale.

Perhaps it’s simplest to say that The Book of All Hours is an almost stereotypically young man’s book; lots of linguistic pyrotechnics, lots of big ideas, characters of inconsistent levels of depth. The archetypal nature of the characters tends to flatten them, to undermine their individuality. More than that, those archetypes, the core group of characters, are almost all young men themselves. There’s only one women in the group — and none in the main group of Covenant antagonists — but, I think at least as significant, there’s no old man either (Don’s older than the others, but not old in the way I have in mind).

You could say, I suppose, that as a young man’s book it’s a celebration of youth and youthful energy; and argue that the villains, the Covenant, are old men. But although they’re more conscious of their age I felt the Covenant didn’t really reflect it. They didn’t seem to act like older people. And I felt overall that the lack of variation in character tended to flatten the book, to make the seeming infinity of the Vellum feel narrow.

You could say, I suppose, that as a young man’s book it’s a celebration of youth and youthful energy; and argue that the villains, the Covenant, are old men. But although they’re more conscious of their age I felt the Covenant didn’t really reflect it. They didn’t seem to act like older people. And I felt overall that the lack of variation in character tended to flatten the book, to make the seeming infinity of the Vellum feel narrow.

Conversely, the book is also aware of tradition, of the literary process of creation that produced the archetypes it plays with. You can see that in the easy play it makes with classical texts, and with the Old Testament. It has to be said that it avoids going beyond the Western tradition — there’s no use made of, say, Chinese myth, for example. Oddly, there’s also little use that I noticed of the Christ story. This is particularly odd as many of the archetypes seem to map, or could be made to map, onto the Christian tradition; as a result it feels like a missed opportunity. One could reasonably say that Duncan was simply being subtle in using the Tom Messenger archetype of the sacrificed young god; I’d argue that the connection would have been more powerful if it was even slightly more explicit.

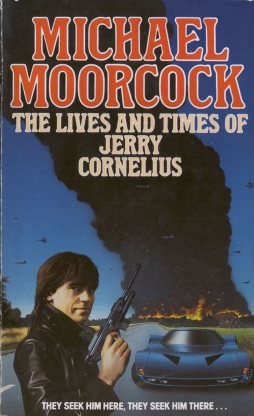

At any rate, beyond the general Western tradition, you can also see more recent influences. The seven archetypes at the heart of reality seem to glance at Gaiman’s Sandman, and to Zelazny’s Amber books (itself an influence on Sandman). The feeling of a conspiracy stretching across myth and time, told through a fractured structure, recalls the Illuminatus! trilogy by way of Grant Morrison’s Invisibles. One family name that recurs in the book, Carter, starts off a series of nods to Lovecraft (and a couple to Burroughs). But I think more than any other one modern writer the book shows the influence of Michael Moorcock.

The use of “Jack Carter” as a ‘JC’ glances back to Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius (whose own initials were meant to glance at Jesus Christ). The play with alternate personas and alternate worlds seems to glance at Cornelius perhaps by way of Bryan Talbot’s Luther Arkwright comic. The use, late in Ink, of the commedia dell’arte as an image for the recurrence of archetypes is very Moorcock, and I’m not sure that’s a good thing. One of the traditional downfalls of the young novelist is the threat of the half-digested influence, and here Duncan’s use of Moorcock threatens to overshadow his own originality, making his indebtedness too obvious.

Still, the obviousness of Duncan`s sources may only be a way in which the true oddness of the book manifests itself, and by true oddness I mean this paradox: for all the newness of the book’s form, it’s actually weirdly familiar. It’s a play with myth told through fragments of narrative in which traditional ideas of character are sacrificed to structural play. And that’s a description of old-school modernism, straight out of the playbook of The Waste Land and Ulysses. It’s very well done in The Book of All Hours, but it can’t help but feel quaint, the unchallenged use of the artistic mode of a few decades past.

Still, the obviousness of Duncan`s sources may only be a way in which the true oddness of the book manifests itself, and by true oddness I mean this paradox: for all the newness of the book’s form, it’s actually weirdly familiar. It’s a play with myth told through fragments of narrative in which traditional ideas of character are sacrificed to structural play. And that’s a description of old-school modernism, straight out of the playbook of The Waste Land and Ulysses. It’s very well done in The Book of All Hours, but it can’t help but feel quaint, the unchallenged use of the artistic mode of a few decades past.

Of course, you can say that this is simply the appropriate mode to use in order to tell the story Duncan wants to tell. And there is some resonance in a writer using an Eliotic form in order to wrestle with the balance of tradition and the individual talent. But I think it points to the basic problem with The Book of All Hours: it’s not radical enough, not down at the core.

Too often the complexities of the book are undercut by the lack of complexity of the characters. Or indeed a lack of complexity in the story’s morality: the tale tends to break down into good guys and bad guys, into a depiction of Covenant control-freaks trying to rewrite the world for their own ends and a disparate group of plucky charismatic rebels trying to outmaneuver them. That’s not necessarily a bad story, but it doesn’t match the formal ambition Duncan has for his text. I felt that in order for the book to succeed, for its grasp to match its reach, it would need to display a human complexity to match its structural cleverness. Instead I felt it self-consciously relaxed into pulp at key moments. It’s well-done pulp, and on its own would be fine. In context, though, I found myself disappointed by the balance Duncan chose between easy good-guy/bad-guy dualities and profound ideas of character.

Overall, I think The Book of All Hours is a major work whose own vaulting ambition lets it down. It’s more than merely promising, but less than what the book itself suggests it could have been. There’s a quote from Jeff VanderMeer on my copy of Vellum which sums it up nicely: “the opening gambit in the career of a mind-blowing colossal talent whose impact will be felt for decades.” I think that’s correct in its assessment of Duncan’s skill as a writer, but also correct in its implication that this is just a beginning. And I think the image of a gambit, of a game being played, is somehow especially apposite. This is a work of strategy and cleverness, and its deployment of language and images, stunning as those often are, feels like moves on a board. I think the book needed its core approach to be newer; and I think it needed more emotional depth. But the sheer amount of invention suggests Duncan will be able to internalise his influences, and some elements of the book — the grappling with the evil of Matthew Shepard’s murder, the quiet epilogue that concludes the work — suggests that he’ll find his way to the more profound sense that I’m missing here. I gather Duncan’s currently working a series of pulp pastiches; I’ll be interested in reading his next move.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

This is a really good review and covers most of what I found interesting about the duology, its deeply engrained modernism, the influence of Joyce and Eliot, etc. It’s really interesting to see someone taking that kind of approach while explicitly dealing with speculative fiction, to see someone using that new mythology. But you’re right in that he doesn’t really do that much with it having taken it. I did enjoy the books, and Duncan is obviously a writer with real talent who’s also seriously committed to speculative fiction. It’s super interesting to see where he goes from here.

Interesting review. I tried reading Vellum and few years back and dropped it. At the time, I thought it was too repetitive.

After a couple of pages, I started wondering what the book had to offer beyond rehashing its mid-century high modernist models. I concluded that if I wanted the verbal pyrotechnics laid on that thick, I could go back to Ezra Pound. I never even got as far as the story, the surface effects were so distracting. Had a similar problem with Mieville’s Perdido Street Station. Maybe now that grad school is more of a receding memory than a recent trauma I’ll try Duncan or Mieville again soon. With your review to go on, looks like Mieville wins.

[…] The Vorrh, John Crowley’s Lord Byron’s Novel and Endless Things, Hal Duncan’s Ink and Vellum (which I’ve called quaint, but quaint in a very traditional high-modernist way), Minister Faust’s The Alchemists of […]