Kimota! and Marvelman

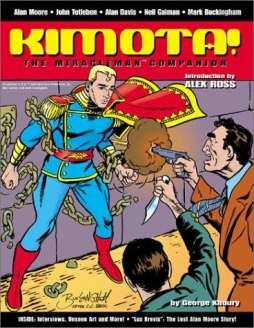

I’m going to take a break this week from the Romanticism and Fantasy posts, because I’ve just finished a fascinating book, and I’d like to talk about it. It’s not a new book, and it’s not a fiction book. It is in fact mainly a collection of interviews about a comic-book character who hasn’t seen print (officially) in almost twenty years. The book is called Kimota!, and the character has been known both as Miracleman and, originally, Marvelman.

I’m going to take a break this week from the Romanticism and Fantasy posts, because I’ve just finished a fascinating book, and I’d like to talk about it. It’s not a new book, and it’s not a fiction book. It is in fact mainly a collection of interviews about a comic-book character who hasn’t seen print (officially) in almost twenty years. The book is called Kimota!, and the character has been known both as Miracleman and, originally, Marvelman.

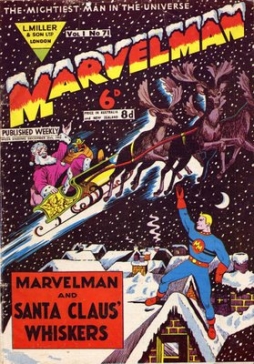

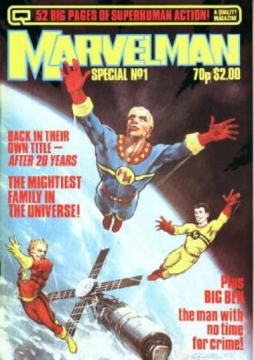

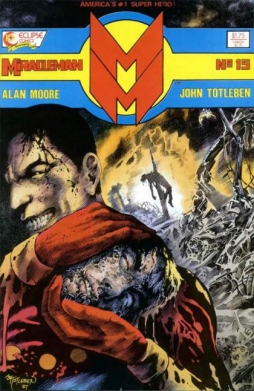

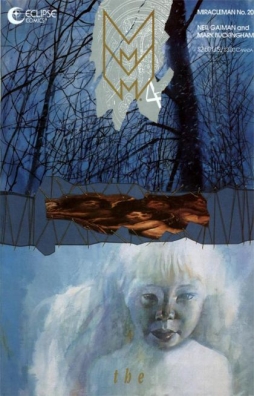

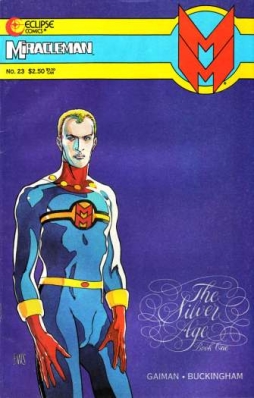

The Marvelman situation is difficult even to describe. Briefly: created in the mid-50s as a British knock-off of Captain Marvel (then the world’s most popular super-hero), the last story of Marvelman’s original run was published in 1963. The character was revived, with his backstory radically re-imagined, by writer Alan Moore for the British magazine Warrior in 1982. Warrior went under before long, but in 1985 Marvelman’s adventures continued, still written by Moore, now published by the American company Eclipse Comics. A few years later, Moore left the book, selecting Neil Gaiman as his successor. Gaiman projected three story arcs; roughly one and a half saw print before Eclipse folded in 1994.

From that time to this, the character has mostly remained in limbo. Marvelman’s the ultimate cautionary tale about the difficulties of copyright law. With every change of publisher, with every change of creator, the question of who owned what grew more complex, more debateable. Two years ago, Marvel Comics bought the copyright from Marvelman’s original creator, and began reprinting some of the character’s old adventures. That’s nice, in many ways, but it’s the Moore and Gaiman work that people have been waiting to see, and waiting to see completed. It may be a while before that happens.

Kimota!, subtitled The Miracleman Companion, was published ten years ago. Edited by George Khoury, it’s a collection of interviews, unpublished art, and other matter to do with Miracleman. Khoury did a good job of getting interviews with people from throughout the character’s publishing history. And setting them out one after another makes for fascinating reading.

Kimota!, subtitled The Miracleman Companion, was published ten years ago. Edited by George Khoury, it’s a collection of interviews, unpublished art, and other matter to do with Miracleman. Khoury did a good job of getting interviews with people from throughout the character’s publishing history. And setting them out one after another makes for fascinating reading.

It’s not necessarily fascinating for the insight it gives into the creative process; Moore’s interview is entertaining, as his interviews always are, but he’s covered much of this ground elsewhere, and the Gaiman interview is interesting but short. Nor is the book fascinating because of the light it sheds on the early 80s comics industry, though that’s fun to see also. What makes the book so fascinating, and so dispiritng, is the way it testifies to the human ability to see the same thing differently; to selectively misremember.

I don’t think many people Khoury talked to deliberately set out to lie to him; I may be wrong, but that’s my impression. But one sees that their stories don’t really sync up. There are some occasional outright contradictions, and many cases where events are ascribed different levels of importance. People remember, or misremember, the past in different ways. The complexity, and contradictions, of the Marvelman story make Kimota! a touchingly and disturbingly human document.

(For a complete explanation of the various copyright issues involving Marvelman, you can look here, or in Steve Bissette’s excellent companion to Neil Gaiman’s fiction, Prince of Stories, which has a good run-down of events up to just before Marvel bought the rights to the character. You can read an excerpt here.)

If nothing else, the book goes a long way toward explaining why we haven’t seen Marvelman brought back. The situation between the various people involved really is that complex. This is a pity, because the Marvelman stories — especially Alan Moore’s work — were ground-breaking for their time, and continue to be a strong influence today.

If nothing else, the book goes a long way toward explaining why we haven’t seen Marvelman brought back. The situation between the various people involved really is that complex. This is a pity, because the Marvelman stories — especially Alan Moore’s work — were ground-breaking for their time, and continue to be a strong influence today.

The sixteen issues Moore wrote were uneven; you can track Moore’s development as a writer as you work your way through them. The art teams changed, especially in the middle issues, and the stylistic variation and uneven quality don’t do the book any favours. The plot is surprisingly thin, and nowadays won’t seem terribly surprising.

But that’s largely because the lessons Moore’s Marvelman taught were assimilated by a generation of creators, who used them in their own books. You can see it both in great things and in small — I suspect it’s no coincidence that the first issue of Kurt Busiek’s Astro City was titled “A Dream of Flying,” the same as the first installment of Marvelman. Moore’s Marvelman was one of the first books to really imagine what would happen if superheroes took over the world and succeeded in creating a utopia. Titles like Marvel’s Squadron Supreme showed heroes trying but failing; Moore questions the utopia his characters make, but gives them the courtesy of imagining they accomplish what they intend.

Books like The Authority followed directly from Marvelman’s example. Moore infused his stories with an awarenes of sex, politics, and indeed sexual politics, that was all but unprecedented in mainstream comics; to an extent the mainstream is still reluctant to follow his lead. It’s almost a truism to say that writers have taken surface elements of his work — the sexuality, the violence — and used them with diminishing effect. Moore’s power as a writer doesn’t come from sex and violence, but from his worldview. It is true that one issue of Marvelman (technically, Miracleman, as the book was then titled) featured a horrific grand guignol vision of a sadistic superhuman massacring the entire population of London. It is also true that it was not that issue that faced real problems with censorship, but an earlier issue in which the birth of a child is shown in graphic — and justified — detail.

Books like The Authority followed directly from Marvelman’s example. Moore infused his stories with an awarenes of sex, politics, and indeed sexual politics, that was all but unprecedented in mainstream comics; to an extent the mainstream is still reluctant to follow his lead. It’s almost a truism to say that writers have taken surface elements of his work — the sexuality, the violence — and used them with diminishing effect. Moore’s power as a writer doesn’t come from sex and violence, but from his worldview. It is true that one issue of Marvelman (technically, Miracleman, as the book was then titled) featured a horrific grand guignol vision of a sadistic superhuman massacring the entire population of London. It is also true that it was not that issue that faced real problems with censorship, but an earlier issue in which the birth of a child is shown in graphic — and justified — detail.

Moore, at his best, infuses his work with a sense of revelation: the things you have read before are nice stories, they seem to say, but this is the truth. I’m sorry, but this is how things really are. One can debate how well-earned that sense is in some of his works. It is literally the case that this is the core narrative of Marvelman, though (as indeed it was of Moore’s Swamp Thing); it’s the story of how the character found out that his whole world, his understanding of who he was and where he came from, was a deliberately-constructed lie. Having learned this, he sets out to gain revenge on the people who lied to him — but is it a truly moral act, to seek revenge? What right does this individual have to seek justice on his own account? What is right, what is wrong, and how should we look at a near-infinitely powerful being who takes the law into his own hands — and eventually chooses to become the arbiter of the law himself?

Moore has a knack for selecting the right image, the right piece of dialogue, to disturb the reader. To hint at a frightening larger world. There is a sense in which his achievement with the super-hero genre — not only in Marvelman, but in Watchmen — is to cross-pollinate it with the horror genre. I’ve often felt that the super-hero is the daylight form of the gothic, that both deal with a sense of cosmic morality, with secrets, with protagonists beyond normal human capability; in Moore’s work we see the balance shifted toward a kind of dusk, heroic and horrific in equal measure.

(Ironically, one of the characteristics of Marvelman-the-character is that he’s really a pretty crap superhero. He looks impressive, he demonstrates his power in dramatically effective ways — but he hardly ever wins a fight against anyone of comparable power, he stumbles into the creation of his utopia, and he and his entire super-powered family twiddle their thumbs for hours without noticing that a genocidal maniac’s on the loose in London.)

(Ironically, one of the characteristics of Marvelman-the-character is that he’s really a pretty crap superhero. He looks impressive, he demonstrates his power in dramatically effective ways — but he hardly ever wins a fight against anyone of comparable power, he stumbles into the creation of his utopia, and he and his entire super-powered family twiddle their thumbs for hours without noticing that a genocidal maniac’s on the loose in London.)

Gaiman’s Marvelman stories are in many ways more technically sound than Moore’s, but the cool polish of his plotting and structure seems to come at the expense of the energy, the disturbing visionary quality of Moore’s work. This is not to diminish them. They are wonderful imaginative constructs, and it’s tragic that his overall storyline hasn’t been finished, that his Marvelman work is not easily available. But I find his work more distant than Moore’s; though it has to be said that where Moore took the present-day world and turned it into a utopia, Gaiman had the far more difficult task of setting stories in that utopia and finding the cracks that would lead to more stories.

From a certain perspective, Gaiman’s work critiques the landmark work that came before his own in a way that’s almost unique to comics. He’s working with the same characters, the same story, as the designated successor to the original creator. In doing so, he found hints and references that he expanded into whole issues, and quite successfully. Moore himself, as I said, questioned the utopia his characters had made; Gaiman sets about illustrating it while also suggesting possible fracture points.

As I say, it would be nice to see his story completed. Frankly, it’s difficult to imagine a revival of the character being taken seriously if Gaiman didn’t get the chance to complete his tale. And difficult to find a writer of the calibre of Moore and Gaiman in the current mainstream comics landscape. (Grant Morrison would be the immediate logical pick, but thematically he’s interested in super-heroes in a different way; on the whole, he examines them to see what is of value in the concept, where Moore and Gaiman have been more likely to take the idea of the super-hero apart, to see what’s behind it. They’re revisionists, where Morrison is a classicist.)

As I say, it would be nice to see his story completed. Frankly, it’s difficult to imagine a revival of the character being taken seriously if Gaiman didn’t get the chance to complete his tale. And difficult to find a writer of the calibre of Moore and Gaiman in the current mainstream comics landscape. (Grant Morrison would be the immediate logical pick, but thematically he’s interested in super-heroes in a different way; on the whole, he examines them to see what is of value in the concept, where Moore and Gaiman have been more likely to take the idea of the super-hero apart, to see what’s behind it. They’re revisionists, where Morrison is a classicist.)

Marvelman’s an oddity in this day and age. Technology and the profit motive have combined to make an ever-larger percentage of everything that has ever been published in comics available legally, in one form or another. If you have the money, you can easily buy a significant amount of the entire Marvel and DC backlists, much of it work of lesser importance than Marvelman. But because of the oddity of copyright law, Marvelman remains out of public sight. It’s an unusual situation, and Kimota! goes some distance toward explaining how it came about — not in the legal sense, but in showing the many personal agendas in play, the different recollections, the different stories about the stories that have been told.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I agree that Moore’s work is often about mixing horror and superpowers, and his work sometimes strikes me as very Lovecraftian, if only in the sense that his “heroes” are often strikingly fragile of mind. I remember in his Captain Britain run, the hero who’d previously been characterized (by other writers) as having typical strength of will and resilience starts reeling at a difficult situation and has such a nervous breakdown that he meekly allows the Fury to just walk up and blow his brains out.

Which also gets at your point that Moore’s heroes are basically lousy heroes because their sense of “heroism” is enabled by a smug sense of superiority. They feel they can do what they like because their superpowers make them impervious to everything, but when faced with an equal, or merely adequate, threat they tend to collapse into sheer panic because underneath it all they’re, well, basically a bunch of wimps who don’t know what it’s like to get punched really hard. I wonder if this was influenced to some degree by the fact that Moore wasn’t really a Marvel reader growing up since they didn’t have much penetration in the U.K. compared to DC, and DC’s heroes were mostly a bunch of omnipotent puzzle-solvers while Marvel’s were down-and-dirty scrappers heavily informed by Jack Kirby’s youthful gang-fighting and WWII experiences.

[…] the book actually comes from a slightly different tradition: it’s a gothic romance. I’ve said a couple of times before that the super-hero story is the daylight form of the gothic; The Scarlet Pimpernel […]

[…] he’s aware of the closeness of the super-hero story to the horror story and to the gothic (something I’ve mentioned before). One of the regions of Astro City is Shadow Hill, a neighbourhood dominated by […]

[…] little while ago, I put up a post here about Miracleman, or, as it was originally known, Marvelman. One of the great ‘lost’ works of […]