Romanticism and Fantasy: The Emergence of the Romantic

Last week, I described the neo-classical attitudes of the Age of Reason, which dominated English literature through most of the 18th century. This week I want to take a look at how and when things changed.

Last week, I described the neo-classical attitudes of the Age of Reason, which dominated English literature through most of the 18th century. This week I want to take a look at how and when things changed.

In 1798 William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge published the first edition of Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poetry that some critics have pointed to as the start of Romanticism in English literature. In fact, you can fairly easily find precursors to one aspect or another of the phenomenon called Romanticism; Blake, for example, was publishing his illuminated prophecies in 1789. But there were a number of works preceding him, as well, and I’m going to look here at some of those texts that seem to pave the way for Romanticism, particularly in the thirty years from 1760 to 1790.

Since I’m interested in Romanticism as a form of fantasy, the texts I’ll look at have to do broadly with the impulse toward fantasy and away from realism. I think the fantastic is a key characteristic of the romantic, while the classical or neo-classical emphasis of the earlier eighteenth century effectively went hand-in-hand with realism. It has to be said that there are other ways to look at Romanticism; it’s certainly true that Wordsworth in particular emphasised the importance of doing away with Enlightenment conventions, and with an outdated poetic diction, in order to focus on life as it was really lived across all social classes. Romanticism is an amorphous term. Writers of the era did not call themselves Romantic, and did not group themselves together the way we group them now. As a result, strict definitions are useless. If you look too long at the vast territory often ascribed to ‘romanticism,’ sooner or later you find significant overlap with ‘the enlightenment.’

On the other hand, ‘the romantic’ would have been recognised in 1800 as a term, as something that was in opposition to ‘the classic.’ The romantic had to do with wildness, mystery, irregularity, and a lack of rules, as against classicism’s order, clarity, structure, and harmony. The romantic was idiosyncratic, the classic universal. The romantic was very nearly, but not quite, what we would now call ‘fantastic.’ Not quite, because while it referred back to medieval romances of knights, magicians, and ghosts, it also included adventure without fantasy — tales of faraway lands, for example — and even certain kinds of nature poetry or descriptive writing. Still, I think it’s fair to say that even where the romantic was not fantastic in and of itself, it referred to elements of writing or of narrative that were easily linked to the fantastic. The second half of the eighteenth century saw a taste for the romantic grow stronger; it therefore saw a rebirth of fantasy, in both ‘literary’ and popular writings.

On the other hand, ‘the romantic’ would have been recognised in 1800 as a term, as something that was in opposition to ‘the classic.’ The romantic had to do with wildness, mystery, irregularity, and a lack of rules, as against classicism’s order, clarity, structure, and harmony. The romantic was idiosyncratic, the classic universal. The romantic was very nearly, but not quite, what we would now call ‘fantastic.’ Not quite, because while it referred back to medieval romances of knights, magicians, and ghosts, it also included adventure without fantasy — tales of faraway lands, for example — and even certain kinds of nature poetry or descriptive writing. Still, I think it’s fair to say that even where the romantic was not fantastic in and of itself, it referred to elements of writing or of narrative that were easily linked to the fantastic. The second half of the eighteenth century saw a taste for the romantic grow stronger; it therefore saw a rebirth of fantasy, in both ‘literary’ and popular writings.

In the same year that Lyrical Ballads was published, a minor critic named Nathan Drake published a book, Literary Hours, arguing that the best poetry (and prose) “seizing hold of the superstitions and fears of mankind, pours forth fictions of the most wild and horrible grandeur.” Drake endorsed writing that “turns chiefly on the awful ministrations of the Spectre, or the innocent gambols of the Fairy” and “founds its imagery upon a metaphysical possibility, upon the appearance of superior or departed beings.” Which is to say that Drake describes a fundamentally romantic art.

There’s nothing particularly notable about Drake. His book didn’t have a special vogue, nor was he saying anything especially striking. The point is that by 1798, not only were young and avant-garde poets arguing for the romantic over the classical, so was a physician writing amateur criticism. General taste was changing toward the romantic, and away from the realist.

Compare Drake with this 1751 review by John Cleland (who, incidentally, had in 1748 written the first English pornographic novel, Fanny Hill): “Romances and novels which turn upon characters out of nature, monsters of perfection, feats of chivalry, fairy-enchantments, and the whole train of the marvellously absurd, transport the reader unprofitably into the clouds, where he is sure to find no solid footing, or into those wilds of fancy, which go for ever out of the way of all human paths.” The romantic here is bad, an error, something that can only mislead the poor reader. That’s a considerable change, from Cleland to Drake, in less than fifty years. How had it come about?

I think it was an evolution over time. Great works changed the consensus on literature, but no one book inaugurated Romanticism. I think you see texts inspiring other texts in a number of ways, suggesting new ways of thinking about writing, and slowly leading to a new era. There are always counter-examples or exceptions to the broad trends that define the literature of an era; works that stand out in opposition to the habits of thought around them. As those counter-examples grow more numerous, you can see tastes changing. I think that’s what happened in the late eighteenth century.

I think it was an evolution over time. Great works changed the consensus on literature, but no one book inaugurated Romanticism. I think you see texts inspiring other texts in a number of ways, suggesting new ways of thinking about writing, and slowly leading to a new era. There are always counter-examples or exceptions to the broad trends that define the literature of an era; works that stand out in opposition to the habits of thought around them. As those counter-examples grow more numerous, you can see tastes changing. I think that’s what happened in the late eighteenth century.

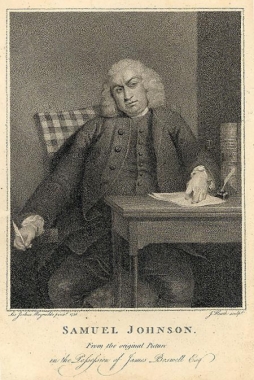

Let’s begin in the year 1760. It was the year George III came to the British throne, leading to a series of political realignments in Parliament as the new King tried to take a more active role in government. The leading literary critic was Doctor Samuel Johnson, an irascible Tory, the ‘Great Cham [Khan] of literature’ whose 1755 Dictionary of the English Language had been hailed as a landmark work. Neo-classical taste reigned supreme.

Mostly. As I say, there were exceptions. To start with, consider the pop-cultural phenomenon of the novel. At the time, the ‘sentimental novel’ or ‘novel of sensibility’ was much in vogue. ‘Sensibility’ was a word that signified much, but is difficult to define precisely. It had to do with moral and aesthetic refinement, and with deep feeling. ‘Sensibility’ implied a high degree of emotionalism. Sensible characters were highly-strung, prone to weeping and fainting. Critics were impatient with the histrionic poses of these characters, and with the way the novel of sensibility aimed to create a sympathetic emotional reaction in readers, bypassing rational thought. The textbook example is Henry Mackenzie’s 1771 The Man of Feeling.

The sentimental novels were broadly realistic, if often escapist. But you could find more extravagant, fantastic fare in novels as well. Examples of the oriental tale, fiction inspired by the Arabian nights, turned up from time to time, often as translations from the French. This is not the place to discuss ‘orientalism’ or the colonial attitudes these tales reflected; only to note that they represented a way of expressing fantasy in a culture not otherwise congenial to the fantastic. It would be a mistake, though, to think that these ‘oriental’ tales were necessarily primarily imaginative. They weren’t all wonder-tales. Many of them, including Johnson’s own 1759 Rasselas, used the backdrop of a distant land simply in order to tell a fable with a specific philosophical point.

The sentimental novels were broadly realistic, if often escapist. But you could find more extravagant, fantastic fare in novels as well. Examples of the oriental tale, fiction inspired by the Arabian nights, turned up from time to time, often as translations from the French. This is not the place to discuss ‘orientalism’ or the colonial attitudes these tales reflected; only to note that they represented a way of expressing fantasy in a culture not otherwise congenial to the fantastic. It would be a mistake, though, to think that these ‘oriental’ tales were necessarily primarily imaginative. They weren’t all wonder-tales. Many of them, including Johnson’s own 1759 Rasselas, used the backdrop of a distant land simply in order to tell a fable with a specific philosophical point.

It’s worth pointing out that by 1760, the great writers that had established the English novel were dead or soon to die. Samuel Richardson’s last novel was published in 1753; he’d die in 1761. Henry Fielding had passed away in 1754. The Scotsman Tobias Smollett was still writing; he’d have been at work on The Life and Adventures of Sir Launcelot Greaves, published in 1762, and in 1771 published Humphrey Clinker — but he died that same year. No great names were coming along to replace them, with one notable exception: Lawrence Sterne, whose Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, had begun to appear in 1759. Tristram Shandy was in many ways a satire on the realistic novel, a series of digressions that’s been hailed as an early forerunner of modernism. In 1760, it must have seemed as though the realistic novel was running out of steam, descending into the self-parody of the sentimental novel and the outright parody of Tristram Shandy.

Poetry was in a somewhat healthier state. But it’s notable in retrospect that Christopher Smart, one of the more accomplished poets of the time, had been imprisoned in a lunatic asylum since 1757, and would continue to be through 1763. Smart’s conventional poetry was celebrated, but it was his work in the madhouse, especially the luminous Jubilate Agno (unpublished until 1939), that is most arresting today.

Worth mentioning here as a notable precursor to Romanticism is graveyard poetry; poems set in and around a graveyard, filled with intimations of mortality and melancholic thoughts on death. It was a form that seemed to be particularly prominent in the 1740s, with Edward Young’s Night Thoughts a particularly successful example; but it was still being written in 1760, with the Seatonian Prize, a major poetry award, given in 1759 to Beilby Porteus’ ‘Death.’ Thomas Gray’s 1751 ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’ is another strong example, but for my purposes Gray’s also notable for his 1757 poem ‘The Bard.’

Worth mentioning here as a notable precursor to Romanticism is graveyard poetry; poems set in and around a graveyard, filled with intimations of mortality and melancholic thoughts on death. It was a form that seemed to be particularly prominent in the 1740s, with Edward Young’s Night Thoughts a particularly successful example; but it was still being written in 1760, with the Seatonian Prize, a major poetry award, given in 1759 to Beilby Porteus’ ‘Death.’ Thomas Gray’s 1751 ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’ is another strong example, but for my purposes Gray’s also notable for his 1757 poem ‘The Bard.’

‘The Bard’ imagined the conflict between the English King Edward I and the last of the Welsh bards. Gray tried to make his poem as historically accurate as he could, though the scholarship then current was nothing like modern professionalised history. It was an example of the antiquarian spirit of the the time, a manifestation of the romantic through the use of history; through, in fact, the re-imagining of history. It came out of a fascination with druids and bards inspired by the antiquarian Joseph Stukeley, and such writings as Stukeley’s 1740 Stonehenge: A Temple Restored to the British Druids. Other writers shared the fascination Stukeley inspired. William Mason wrote two tragedies based on English history, Elfrida and Caractacus (1752 and 1759, respectively); the poet William Collins wrote odes inspired by Stukeley’s fantastical notions of history.

(The 18th century, I should note, was no stranger to fantasticated history. The Freemasons had emerged in their modern form in 1717, but I think they had less to do with antiquarianism or even the fantastic than with utopian Enlightenment thought. Conversely, Sir Francis Dashwood’s Mad Monks of Medmenham, known to history and to comic book fans as the Hell-fire Club, were a mixture of anti-clerical satire and hedonism. Neither were really products of the spirit I’m trying to get at here.)

(The 18th century, I should note, was no stranger to fantasticated history. The Freemasons had emerged in their modern form in 1717, but I think they had less to do with antiquarianism or even the fantastic than with utopian Enlightenment thought. Conversely, Sir Francis Dashwood’s Mad Monks of Medmenham, known to history and to comic book fans as the Hell-fire Club, were a mixture of anti-clerical satire and hedonism. Neither were really products of the spirit I’m trying to get at here.)

This kind of antiquarianism was important because, I’d argue, it provided a channel through which the romantic and fantastic could re-enter literature. If the romance was an outmoded form, then it was through investigating and reconsidering history that one could approach it. Interest in the sixteenth-century poet Edmund Spenser and his fantasy allegory The Faerie Queene was revived in the 1750s, for example, inspiring a significant essay by poet-critic Thomas Warton in 1754. The essay’s interesting because Warton tries to balance his personal taste, which inclines to the romantic, against the neo-classical critical ideas of his time: “It is true that [Spenser’s] romantic materials claim great liberties; but no materials exclude order and perspicacity.” Of Spenser and his fellow romance-writers, Warton carefully says “I have found no fault in general with their use of magical machinery; notwithstanding I have so far conformed to the reigning maxims of modern criticism as to recommend classical propriety.” We’re a long way from Nathan Drake’s endorsement of ghosts and magic. Warton’s aware, perhaps excessively so, that the taste of his age is entirely against what he elsewhere in his essay calls “Gothic [medieval] ignorance and barbarity.”

You can’t really blame him. Two years later his brother, Joseph, published the first part of an Essay on Pope which, as the title implies, examined the work of Alexander Pope critically — and drew furious censure for being insufficiently appreciative of the great man. Significantly, in addition to slighting Pope, Warton argued that poetry had suffered from its abandonment of “descriptions and enchantment.” The backlash was so strong that Warton didn’t publish the second part of his essay for twenty-six years, by which time things had begun to change.

In talking about these essays I’m trying to look at how the aesthetic sense changed in Britain, how aesthetics expanded to include the fantastic. Accordingly, it’s important to mention here the 1757 essay by Irish writer and journalist Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful. The sublime, for Burke, was something beyond reason: “far from being produced by them, it anticipates our reasonings, and hurries us on by an irresistible force. Astonishment, as I have said, is the effect of the sublime in its highest degree; the inferior effects are admiration, reverence, and respect.” The sublime was linked to terror, to awe — and implicitly to the fantastic: “Every one will be sensible of this, who considers how greatly night adds to our dread, in all cases of danger, and how much the notions of ghosts and goblins, of which none can form clear ideas, affect minds which give credit to the popular tales concerning such sorts of beings. … For this purpose too the Druids performed all their ceremonies in the bosom of the darkest woods, and in the shade of the oldest and most spreading oaks.” Burke doesn’t call his sublime ‘romantic,’ but the two concepts would soon become deeply linked.

In talking about these essays I’m trying to look at how the aesthetic sense changed in Britain, how aesthetics expanded to include the fantastic. Accordingly, it’s important to mention here the 1757 essay by Irish writer and journalist Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful. The sublime, for Burke, was something beyond reason: “far from being produced by them, it anticipates our reasonings, and hurries us on by an irresistible force. Astonishment, as I have said, is the effect of the sublime in its highest degree; the inferior effects are admiration, reverence, and respect.” The sublime was linked to terror, to awe — and implicitly to the fantastic: “Every one will be sensible of this, who considers how greatly night adds to our dread, in all cases of danger, and how much the notions of ghosts and goblins, of which none can form clear ideas, affect minds which give credit to the popular tales concerning such sorts of beings. … For this purpose too the Druids performed all their ceremonies in the bosom of the darkest woods, and in the shade of the oldest and most spreading oaks.” Burke doesn’t call his sublime ‘romantic,’ but the two concepts would soon become deeply linked.

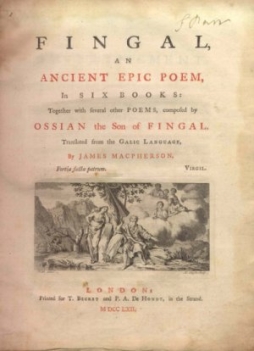

So there were some of the things in the background in 1760, when a remarkable book was published. It came about following a meeting late the year before, between playwright John Home and 24-year-old James Macpherson, a teacher and tutor. Macpherson by all accounts was an irritable, bad-tempered man; he may have been irked by the critical and commercial failure, in 1758, of his poem The Highlander, which told a medieval, romantic tale in neoclassical heroic couplets. At any rate, when Macpherson met Home, he happened (suspiciously, in some people’s view) to have some samples of unpublished Gaelic poems with him; Home asked for an English translation, and Macpherson obliged. Home was impressed. Reluctantly, Macpherson gave Home some more translations a few days later. An excited Home took the poems to Edinburgh. The literary élite were as impressed as Home, and urged Macpherson to publish his translations — which he did, in 1760, as Fragments of Ancient Poetry, Collected in the Highlands of Scotland, and Translated from the Galic or Erse Language. There were sixteen fragments in the book; twelve of them sprang directly from Macpherson’s own imagination.

The Fragments were long pieces that told tragic and heroic tales of legendary heroes. They were massively popular, and Macpherson followed them with more of his translations. Fingal, An Ancient Epic Poem in Six Books: Together with Several Other Poems, Composed by Ossian the Son of Fingal came out in 1762. The title epic has some striking plot resemblances to Macpherson’s earlier Highlander, but nobody seems to have noticed. The next year, Macpherson produced another epic, Temora, with a collection of all the poems following in 1765.

The poems were supposedly based on works composed by a third century bard, Ossian, and told stories of war, battles, and ghosts. Macpherson actually had used real Gaelic poems in composing them, but extremely freely, and inventing much of his material. His language was dramatic and powerful, a kind of prose poetry based around parallelisms and invocation. They were a tremendous popular sensation. Macpherson’s epics, his supposed ‘northern Homer,’ spurred the imagination of readers across Europe.

The poems were supposedly based on works composed by a third century bard, Ossian, and told stories of war, battles, and ghosts. Macpherson actually had used real Gaelic poems in composing them, but extremely freely, and inventing much of his material. His language was dramatic and powerful, a kind of prose poetry based around parallelisms and invocation. They were a tremendous popular sensation. Macpherson’s epics, his supposed ‘northern Homer,’ spurred the imagination of readers across Europe.

But not that of Samuel Johnson. Johnson at once believed the poems to be fakes. More than that, he didn’t think they were very good. In 1763, Johnson was introduced to a young Scotsman named James Boswell, who would go on to make Johnson the subject of one of the greatest biographies in world literature; according to Boswell, one supporter of Ossian “asked Dr. Johnson whether he thought any man of a modern age could have written such poems? Johnson replied ‘Yes, Sir, many men, many women, and many children.’” Johnson would go on to lead the opposition to the Ossianic poems; increasingly, it would be a battle not about the quality of the poems, but their status as genuine archaic works. Ultimately, after Macpherson’s death in 1796, a committee headed by Henry Mackenzie (the sentimental novelist) would conclude that Macpherson had treated his material very freely; the poems, they concluded, were fakes. They continued to be popular for some time, nevertheless.

In fact, the Ossianic poems inspired or harmonised with a number of other works that came out at about the same time. In 1762, the year of Fingal, a churchman named Richard Hurd published Letters on Chivalry and Romance. This was a work of criticism that actively championed the ‘Gothic’ over the classical. At the time, ‘Gothic’ meant, roughly, ‘medieval’ and ‘barbarous;’ the Goths originally were a Germanic people, barbarian tribes who helped to bring about the fall of Rome. Until Hurd’s essay, the term had been one of abuse, signifying superstition and backwardness. Hurd turned the accepted value of the word on its head, writing in praise of chivalry and of medieval romances. For Hurd, the Gothic and northern, the romantic, opposed the classical and southern with a distinctive art and culture of its own.

The same year also saw the publication of a historical romance set in the Middle Ages, John Leland’s Longsword. “The outlines of the following story, and some of the incidents and more minute circumstances, are to be found in the antient English historians,” Leland claimed. Like Macpherson, he had to justify his romance with an appeal to history. As it turned out, Longsword sold well enough, though it made virtually no impact among critics; at any rate, a more extravagant medieval fantasy soon followed.

The same year also saw the publication of a historical romance set in the Middle Ages, John Leland’s Longsword. “The outlines of the following story, and some of the incidents and more minute circumstances, are to be found in the antient English historians,” Leland claimed. Like Macpherson, he had to justify his romance with an appeal to history. As it turned out, Longsword sold well enough, though it made virtually no impact among critics; at any rate, a more extravagant medieval fantasy soon followed.

In 1764, Hugh Walpole, the publisher of Thomas Gray, had a bad dream. Walpole was something of an eccentric, who in 1750 had begun decorating and remodeling his home, Strawberry Hill, in a whimsical ‘gothic’ style, with random battlements and arches and stained-glass windows. He filled it with antiques and collectibles; and perhaps it was these items of memorabilia that gave him the dream, a nightmare about a giant hand in armour. On waking, he composed a wild medieval ghost story around the dream, writing and publishing it within two months. The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Tale was a chaotic, improbable book, involving tombs, giant phantoms, and a beautiful young woman threatened with marriage to the lord of a ruined castle. It was a huge success.

Walpole claimed in the first edition that it was a translation from an Italian original, though in the second edition he admitted his authorship. Again the medieval, gothic past inspires fantasy; and again there is a ducking-away from authorial responsibility. The past not only inspires the tale, it justifies the telling of it. For a modern writer to write seriously of the fantastic, the heroic, the romantic, the past — that’s difficult to accept. Consider: also in 1764, writer James Ridley published an Arabian fantasy, Tales of the Genii. Not only did he publish under a pseudonym, as Sir Charles Morell, but the book claimed to be “translated from the Persian.” It was a double evasion.

I mentioned last week that the 18th century emphasis on realism seemed to come at the expense of a way of reading that refused to consider a story as either true or false. The neo-classic ideology said that stories were either true and improving, or wrong and therefore capable of leading readers into error. Samuel Johnson opposed Macpherson’s Ossianic poems, I think, not just because they were forgeries, not just because lies were told about the texts, but because the texts were lies in themselves. From a certain point of view, the hesitancy to proclaim authorship of these romances, the veils thrown up around them, seem to re-establish the uncertainty of the truth of a text. Was The Castle of Otranto a modern production, or could it be excused as a romance written by ignorant ‘goths’ who didn’t know any better?

I mentioned last week that the 18th century emphasis on realism seemed to come at the expense of a way of reading that refused to consider a story as either true or false. The neo-classic ideology said that stories were either true and improving, or wrong and therefore capable of leading readers into error. Samuel Johnson opposed Macpherson’s Ossianic poems, I think, not just because they were forgeries, not just because lies were told about the texts, but because the texts were lies in themselves. From a certain point of view, the hesitancy to proclaim authorship of these romances, the veils thrown up around them, seem to re-establish the uncertainty of the truth of a text. Was The Castle of Otranto a modern production, or could it be excused as a romance written by ignorant ‘goths’ who didn’t know any better?

One way or another, Ossian continued to have an effect; 1764 saw the publication of Evan Evans’ translations from Welsh, Some Specimens of the Poetry of the Ancient Welsh Bards. There is much to be written about the interplay of nationalisms at work in the pasts being dredged up and re-imagined; even the new value Hurd put on ‘gothic’ highlighted the northernness of ‘gothic’ writing. The English were a Germanic people, unlike the Latins who provided classical models. The Welsh bardic literature, like the Ossianic poems, dated back to the medieval era, which by now seemed to be in vogue; though, unlike Ossian, Evans’ collection was genuine.

Evans had been encouraged in his work by a churchman named Thomas Percy, who for several years had been preparing a collection of ballads based on a 17th-century folio he’d acquired some time before. Ballads were a popular form, narrative poems that told tales of medieval legends, of Robin Hood and King Arthur. Percy, who published the first translation of a Chinese novel into English in 1761 and a collection of translations from the Icelandic in 1763, finally produced his Reliques of English Poetry in 1765. It was a best-seller, catching the popular imagination, and over the next couple of decades further collections of ballads would appear in its wake.

The Ossianic poems, The Castle of Otranto, and the Reliques between them seemed to offer something new to readers. More than that, Hurd and to a lesser extent Burke provided a theoretical framework through which to look at this writing, giving the romantic and fantastic some value of its own. This all had an impact. Gray’s collected poems, for example, published in 1768, included not only “The Bard” but a number of other poems on gothic and Celtic themes. And, in 1769, Walpole found himself contacted by a young man from Bristol who claimed to have found some medieval poems; was Walpole interested in publishing them? Walpole ultimately was not, after consultation with experts comvinced him that the poems, supposedly by a 15th-century knight named Thomas Rowley, were actually by 18th-century teenager Thomas Chatterton, who apparently had been caught up in the craze for medieval writing.

The Ossianic poems, The Castle of Otranto, and the Reliques between them seemed to offer something new to readers. More than that, Hurd and to a lesser extent Burke provided a theoretical framework through which to look at this writing, giving the romantic and fantastic some value of its own. This all had an impact. Gray’s collected poems, for example, published in 1768, included not only “The Bard” but a number of other poems on gothic and Celtic themes. And, in 1769, Walpole found himself contacted by a young man from Bristol who claimed to have found some medieval poems; was Walpole interested in publishing them? Walpole ultimately was not, after consultation with experts comvinced him that the poems, supposedly by a 15th-century knight named Thomas Rowley, were actually by 18th-century teenager Thomas Chatterton, who apparently had been caught up in the craze for medieval writing.

Walpole was right about Chatterton’s authorship of the Rowley poems, but seems to have overlooked the actual poetic accomplishment in Chatterton’s verses. Chatterton’s story ended unhappily; he moved to London to try to make a living as a writer, failed, and died at 17 from an overdose of arsenic. He’s typically believed to have killed himself, though writer Peter Ackroyd has suggested, perhaps with tongue in cheek, that Chatterton actually misjudged the dosage of an 18th-century cure for venereal disease. At any rate, as a suicide Chatterton became a powerful symbol to the next generation — the poet who dies neglected, his genius unrecognised, still a youth. He’s also a sign of the need to hide one’s poetic vocation, and one’s romantic sympathies, behind a false identity, behind a mask out of the past.

Still, the new enthusiasm for the romantic was spreading. It may be worth noting that in 1769 actor and theatre manager David Garrick held a Shakespeare Jubilee, commemorating (five years too late) the two hundredth anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. Garrick had always argued in favour of maintaining Shakespeare’s original text, comparing manuscripts where possible, and shunning 18th-century ‘improvements’ made to the plays (one version of Lear was produced with a happy ending). This was controversial; in 1759, writer Oliver Goldsmith had complained about “the revival of those pieces of forced humour, far-fetched conceit and unnatural hyperbole which have been ascribed to Shakespeare” — in other words, he’d complained about using the original texts of the plays. Ten years later, though, Garrick was celebrated as “the Poet’s High Priest” by scholars.

Earlier in the century, Shakespeare had been considered a poet of genius, but irregular; a writer who would have done better had he observed the rules. That was changing, not long after the re-evaluation of his contemporary Spenser. Mark Brewer, in his Pleasures of the Imagination, captures the change in perspective on Shakespeare: “His imagination, his literary inventiveness, even his ‘faults’ in transgressing the rules of the classical unities, were thought of as uniquely British, in contrast to the cold classicism of a Racine or a Corneille.” It may not be coincidence that the first critical edition of Chaucer came not long after, in 1778, for the first time with an analysis of the proper Middle English prononciation and scansion.

Earlier in the century, Shakespeare had been considered a poet of genius, but irregular; a writer who would have done better had he observed the rules. That was changing, not long after the re-evaluation of his contemporary Spenser. Mark Brewer, in his Pleasures of the Imagination, captures the change in perspective on Shakespeare: “His imagination, his literary inventiveness, even his ‘faults’ in transgressing the rules of the classical unities, were thought of as uniquely British, in contrast to the cold classicism of a Racine or a Corneille.” It may not be coincidence that the first critical edition of Chaucer came not long after, in 1778, for the first time with an analysis of the proper Middle English prononciation and scansion.

It’s probably safe to say that no great lasting work of fantasy was produced in Britain in the 1770s, but that doesn’t mean that the change in taste was rolled back. In 1771 poet James Beattie published the first part of The Minstrel, a long and immensely popular poem about the development of a poet “in Gothic days.” In 1773 Anna Laetitia Aiken published with her brother a collection of Miscellaneous Pieces, which included essays “On Romances” and “On the Pleasure Derived from Objects of Terror,” accepting that there was pleasure in the romantic and trying to determine why. Along with them was a fragment of a Gothic story, “Sir Bertrand,” which still turns up in anthologies of gothic fiction today. Notable here is the fact that the piece — about a medieval knight on an adventure who comes to a ruined castle filled with ghosts and magic — is deliberately designed as a fragment, a story with no ending.

More significantly, In 1774 Thomas Warton (the essayist on Spenser from the 50s) published the first part of his influential History of English Poetry from the Close of the Eleventh to the Commencement of the Eighteenth Century, with successive volumes coming in 1777 and 1781. It was another key document in shifting, not just current taste, but the way people thought about past literature and past poetry. Warton included a dissertation on “The Origin of Romantic Fiction in Europe” (largely wrong in its conclusions, but still a sign of how seriously he was prepared to take the subject), and his book reflected his interest in the romantic over the classical.

Still, neo-classicism and the Age of Reason were far from dead. Even if people professed to be appalled by the morality on display in Lord Chesterfield’s Letters to His Son, published in 1774 after Chesterfield’s death — Johnson, who had his own grudge against Chesterton, said that the letters taught “the morals of a whore and the manners of a dancing-master” — the Enlightenment continued. 1775 saw the perfection of the steam-engine by James Watt, foreshadowing a coming technological revolution. 1776 saw not only the American Revolution, soon followed by a Constitution and Bill of Rights inspired by Enlightenment ideals, but also the publication of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, which imagined an economic system in which human beings were all perfectly rational actors. 1776 also saw the publication of the first volume of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, where antiquarianism gave way to something like a modern sense of history.

Still, neo-classicism and the Age of Reason were far from dead. Even if people professed to be appalled by the morality on display in Lord Chesterfield’s Letters to His Son, published in 1774 after Chesterfield’s death — Johnson, who had his own grudge against Chesterton, said that the letters taught “the morals of a whore and the manners of a dancing-master” — the Enlightenment continued. 1775 saw the perfection of the steam-engine by James Watt, foreshadowing a coming technological revolution. 1776 saw not only the American Revolution, soon followed by a Constitution and Bill of Rights inspired by Enlightenment ideals, but also the publication of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, which imagined an economic system in which human beings were all perfectly rational actors. 1776 also saw the publication of the first volume of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, where antiquarianism gave way to something like a modern sense of history.

On the other hand, 1777 saw the publication of The Champion of Virtue: A Gothic Story, by Clara Reeve, a novel directly inspired by The Castle of Otranto. Again, the book was presented in its first edition as a translation of an old manuscript. In the second edition, published in 1778, Reeve acknowledged her authorship, and changed the title to The Old English Baron. It was a more sedate book than The Castle of Otranto, with a clearer moral purpose; that didn’t stop it from selling well.

It was also at this time that Chatterton’s Rowley poems were first widely published, at first (in 1777) as genuine medieval works and then (in 1778) as forgeries. Coincidentally, it was also at about this point that Samuel Johnson published his last major work, a series of critical studies, The Lives of the Poets (1779 through 1781). The dialogue between the romantic and classical was ongoing, but with Johnson’s death in 1784 it’s tempting to consider the classical as being in retreat. In 1782 Joseph Warton felt able to reprint his controversial 1756 Essay on Pope, along with the previously-unpublished second volume. The gothic, in literature and in architecture, was everywhere. In 1783 Sophia Lee began publishing her best-selling novel The Recess (through 1785), a historical fiction with strong gothic colouring. In 1778 two respectable Anglo-Irish ladies ran away with each other and settled near the town of Llangollen, where over the coming decades they would entertain literary visitors from across Europe; the home they designed for themselves was decorated in the gothic style, and filled, like Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, with medieval furniture and mementos.

Even while the medieval ‘gothic’ past was being re-evaluated, the rationality of the classical world was being undermined. The erotic art discovered at Pompeii in recent years had suprised people considerably; in 1786 Richard Payne Knight, a leading art collector, published An Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus, which not only claimed to have found contemporary worship of the pagan god Priapus in an Italian village, but also suggested that the worship of fertility was a key part of religions through the ages — including the Christian religion. His book was filled with careful study of surviving texts and archaeological artifacts; it also contained illustrations that were shocking even to a notoriously libertine age. It was never actually published, as such, but was widely distributed in privately-printed copies. In the long run, it was not only significant for the study of comparative mythology, but also for the development of what we now call neo-paganism.

Even while the medieval ‘gothic’ past was being re-evaluated, the rationality of the classical world was being undermined. The erotic art discovered at Pompeii in recent years had suprised people considerably; in 1786 Richard Payne Knight, a leading art collector, published An Account of the Remains of the Worship of Priapus, which not only claimed to have found contemporary worship of the pagan god Priapus in an Italian village, but also suggested that the worship of fertility was a key part of religions through the ages — including the Christian religion. His book was filled with careful study of surviving texts and archaeological artifacts; it also contained illustrations that were shocking even to a notoriously libertine age. It was never actually published, as such, but was widely distributed in privately-printed copies. In the long run, it was not only significant for the study of comparative mythology, but also for the development of what we now call neo-paganism.

But the story of the 1780s, I think, was the coming of a new generation of writers, one shaped by Ossian, by the critical studies of the Wartons, by Percy’s Reliques and by the early gothics. In 1783 William Blake published his first work, a collection of Poetical Sketches. In 1786 Robert Burns first saw print. In 1787 Mary Wollstonecraft published her first work, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, followed the next year by her first novel, Mary: A Fiction. 1787 also saw the first published work by William Wordsworth. New, strong writers were emerging.

Had things changed in the literary world by then? Let’s look at three fantasies from the year 1786. In 1785, a German professor named Rudolf Erich Raspe, who had fled to England just ahead of the law, published a book called Baron Münchhausen’s Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia. Raspe loosely based his charismatic rogue of a main character, wandering from one tall tale to another, on an actual German noble, who reportedly was not amused. The book was translated into German and expanded, then translated back into English in 1786; it’s this version that has become best known. It’s a fun, rollicking book, but it’s not much like the other texts I’ve mentioned so far in this post. In its refusal to take itself seriously, it’s far more like Gulliver’s Travels — and later editions of the book specifically compare the good Baron to Lemuel Gulliver. It’s a book from a different, older tradition than the new gothics, and seems to me to stand out as something distinct from the emerging taste for the romantic.

1786 also saw the publication of an anonymous novel called Rajah Kisna. It seems to have been a potboiler fantasy set in India, and it was brusquely dismissed by critics. It was part of the world of popular ephemera; it’s rare for such novels to have any lasting life or significantly change the critical conversation. Although descriptions suggest it was filled with magic and excitement, it made no lasting impact. Being romantic, then, was not enough to make a book connect with an audience.

1786 also saw the publication of an anonymous novel called Rajah Kisna. It seems to have been a potboiler fantasy set in India, and it was brusquely dismissed by critics. It was part of the world of popular ephemera; it’s rare for such novels to have any lasting life or significantly change the critical conversation. Although descriptions suggest it was filled with magic and excitement, it made no lasting impact. Being romantic, then, was not enough to make a book connect with an audience.

But as it happened, 1786 saw the publication of another oriental tale, a translation from a French text written by an Englishman. William Beckford’s Vathek is often called a gothic; in fact it’s an odd and perhaps unique fusion of gothic and arabesque. There’s a real dark power to it, as it follows its Muslim protagonist through the rejection of God and a descent into Hell. It’s a lasting fantasy classic, and shows the way things were going in the future. 1789 would see the first novel published by Ann Radcliffe, The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne; although Radcliffe had a much more conventional morality than the decadent Beckford, her work — 1790 saw the publication of A Sicilian Romance, and 1791 brought The Romance of the Forest — led to the massive popularity of the gothic horror novel in the 1790s.

It seems to me that by 1790 the gothic and fantastic had been established in the British literary scene, on both a popular and critical level, in a way they hadn’t been before the publication of Macpherson’s Fragments in 1760. It was a slow process of evolution, but over the course of thirty years readers and critics became increasingly open to the romantic. Things had changed. The generation of writers then emerging understood the fantastic and romantic in a way that their predecessors hadn’t; they’d grown up with it. In future posts, we’ll see what that led to.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Ah, now I know what Clark Ashton Smith was doing with his story, “The Third Episode of Vathek.” While on a campaign to fill the gaps in my pulp education, I read it with no familiarity with Beckford. It’s still not my kind of thing, but at least now I understand better what he was up to.

What is the current status of MacPherson’s Ossian poems? Do people still read them for reasons other than literary-historical background? And quite apart from what Boswell thought of them, do you find them an engaging read now?

I slogged through all of Christopher Smart’s Jubilate Agno once. It has a lot of stunning lines, and a few stunning passages, but no bones. That said, I agree with Boswell on this one thing: I had as lief pray with Kit Smart as with any one else.

I gather that the Ossian poems are going through a serious re-evaluation in academia. Personally, I like them a lot. They’re heavy going in large doses, which is something I don’t normally say about anything; but read a bit at a time they’re great. (Maybe I should just give them another serious go.)

On Jubilate Agno: I don’t disagree at all, but I find that when it’s good it’s *so* good it really makes the poem. I have to admit that knowledge of the poet’s circumstances may affect my reading of it — it’s touching to think of Smart in the asylum, watching his cat play and writing these incredible verses (to his cat, among other things). Still … there’s something about his imagery that seems so explosive, so … direct.

(Was it Boswell or Johnson who said that about praying with Smart? Or not a fan of Johnson?)

I confess, I’ve never made it through the whole Life of Johnson, only excerpts as necessary. It’s those famous misogynistic quotes–it’s hard to work myself up to get into a book when I know that kind of ugliness will be waiting for me in the pages ahead.

The bit about praying with Smart is attributed to Johnson. The internet tells me it’s in the Life, from a conversation with a Dr. Burney.

I do love Smart’s lines to his cat. He’s also got a line about the owl being the winged cat that, in addition to being vivid and wonderful, is actually pretty clever about ecological niches.

[…] Days NewsThe Book of NowPeople With Hearing Disabilities Say Goodbye To The Need For Sign LanguageBlack Gate […]

[…] Romanticism and the development of fantasy fiction; you can find previous installments here, here, here, and here. To recap so far: I’ve looked at the emergence of the fantastic in English literature […]

[…] with an overview of the neo-classical eighteenth century the Romantics revolted against, considered the Romantic themes in English writing from 1760 to about 1790, then looked at elements of fantasy and Romanticism in France and Germany before returning to […]

[…] an overview of the neo-classical eighteenth century that the Romantics revolted against, considered the Romantic themes in English writing from 1760 to about 1790, then looked at elements of fantasy and Romanticism in France and Germany before returning to […]