William Blake and the Nature of Fantasy

Perhaps my favourite fantasy writing is arguably not fantasy at all. The epics and prophecies of William Blake certainly read like fantasy to many people, I think, albeit fantasy in a distinctive, unfamiliar form. But is the word appropriate? Blake himself was a visionary — he literally saw visions — and may well have believed that some at least of his writing was literally true. Does the definition of fantasy reside in the writer, or the reader? And how would Blake himself want his writing to be viewed?

Perhaps my favourite fantasy writing is arguably not fantasy at all. The epics and prophecies of William Blake certainly read like fantasy to many people, I think, albeit fantasy in a distinctive, unfamiliar form. But is the word appropriate? Blake himself was a visionary — he literally saw visions — and may well have believed that some at least of his writing was literally true. Does the definition of fantasy reside in the writer, or the reader? And how would Blake himself want his writing to be viewed?

Farah Mendlesohn, in her book Rhetorics of Fantasy, argued that the term ‘fantasy’ did not necessarily apply to the works of Latin American magic realist writers. As I understand her, she argues that the cultures of these writers are distinct from the culture that produced ‘fantasy fiction,’ and that the writers therefore stand in a different relationship of belief to the fiction. Magic realist texts “are not meant to act as genre text. Instead, the world from which the text was written is the primary world. It only becomes fantastical because we Anglo-American readers are outsiders. … Magic realism … is written with the sense of fading belief. If we are looking for some form of it, we need the literature of a similar culture, one in which the presence of other powers is a real and vibrant thing, even if it must exist alongside scientific rationalism.”

I don’t know whether what Mendlesohn describes is necessarily a cultural outlook, or whether it can be a personal one. She acknowledges it can apply to writing from the American South. But take John Crowley’s novel quartet The Solitudes, which seems like a North American piece of magic realism and which very carefully builds in explanations for its metaphysical elements — Crowley suggests that the world remakes itself on occasion, with different rules and a rewritten history each time; magic might have worked once, the books say, but when the world last changed, not only did magic stop working, but history itself was changed so that in fact magic now never has worked. Does one need to concern oneself with Crowley’s own philosophical positions before determining whether his writing is fantasy? (In fact, it’s a more complicated question than that; briefly, the characters are half-aware that they’re characters in a story, and the text itself unfolds aware of its nature as a text. Whether this makes it more fantastic or less is an interesting point, but not what I want to talk about here.)

I suppose one could argue that Crowley’s culture supports a certain reading of his work, in general terms; there’s a shared cultural understanding of what fantasy is, and how his work relates to it. But that cultural understanding has evolved over time. John Clute has argued that fantastika — the related genres of science fiction, fantasy, and horror — really only began around 1750 or 1760, about the time that The Castle of Otranto and the Ossianic poems were first published. It has been said that in earlier periods, the general understanding of stories had nothing to do with true or false — a story was a story. By the mid-eighteenth century, a greater sense of stories as being either fact or fiction had developed, along with a body of self-consciously mimetic literature, and a critical ideology stating that the best fiction was that which was closest to fact. The late eighteenth century, in other words, is a period of the thinning of magic from the understanding of the English-speaking world, and from much critically-approved English literature.

I suppose one could argue that Crowley’s culture supports a certain reading of his work, in general terms; there’s a shared cultural understanding of what fantasy is, and how his work relates to it. But that cultural understanding has evolved over time. John Clute has argued that fantastika — the related genres of science fiction, fantasy, and horror — really only began around 1750 or 1760, about the time that The Castle of Otranto and the Ossianic poems were first published. It has been said that in earlier periods, the general understanding of stories had nothing to do with true or false — a story was a story. By the mid-eighteenth century, a greater sense of stories as being either fact or fiction had developed, along with a body of self-consciously mimetic literature, and a critical ideology stating that the best fiction was that which was closest to fact. The late eighteenth century, in other words, is a period of the thinning of magic from the understanding of the English-speaking world, and from much critically-approved English literature.

Now it’s notable that Blake’s work did not receive much critical recognition during his life (though Samuel Taylor Coleridge is on record as being impressed with his work). Born in 1757, Blake died in 1827, and certainly he was a man of his time, with many of the understandings and prejudices that implies. But he understood the process of thinning going on around him. He consistently opposed the materialistic, rationalistic understanding of the world that was producing the “dark Satanic mills” of the early industrial era. When he saw visions, he accepted them for what they were. Is that fantasy, or not?

When reading his work, it’s difficult to tell how much he actually believed in the literal truth of the world he unveiled. He’s a man who could cheerfully write of a new home that “Heaven opens here on all sides her golden Gates … voices of Celestial inhabitants are more distinctly heard & their forms more distinctly seen & my Cottage is also a Shadow of their houses.” Hence the question: does it matter what he believed?

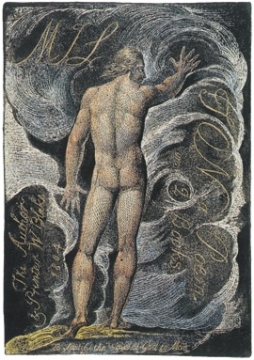

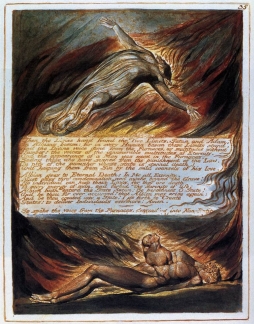

In much of his work, Blake combined poetry and illustrations in a distinctive engraving process which he said was explained to him in a vision by his dead brother Robert (Blake, incidentally, made a strong distinction between visions, such as the appearance of Robert, and ghosts, which he said only appeared to unimaginative people). Most of his major writings appeared in this form, a kind of self-publishing in which each copy was a distinct artifact with individual colouration. Although the integration of text and image seems to suggest contemporary comics, in fact the way one reads them is nothing like the way we read comics; they’re much more like medieval illuminated manuscripts.

In much of his work, Blake combined poetry and illustrations in a distinctive engraving process which he said was explained to him in a vision by his dead brother Robert (Blake, incidentally, made a strong distinction between visions, such as the appearance of Robert, and ghosts, which he said only appeared to unimaginative people). Most of his major writings appeared in this form, a kind of self-publishing in which each copy was a distinct artifact with individual colouration. Although the integration of text and image seems to suggest contemporary comics, in fact the way one reads them is nothing like the way we read comics; they’re much more like medieval illuminated manuscripts.

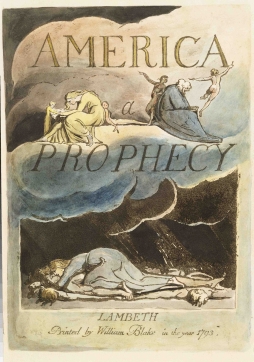

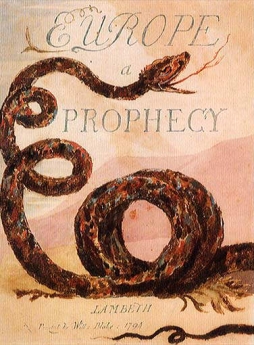

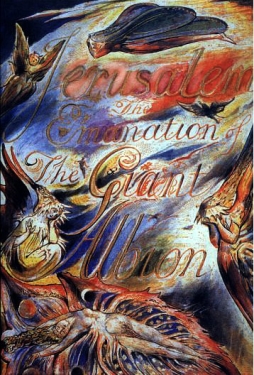

Among the important works Blake produced in this way were a collection of powerful brief lyrics, Songs of Innocence and of Experience; a wildly original autobiographical-philosophical-visionary tract called The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; parables of sexual understanding thwarted or perverted (The Book of Thel and Visions of the Daughters of Albion); short prophecies which found apocalyptic importance in contemporary political events while also presenting a new conception of the origin of the physical universe and of humanity (America, Europe, The Song of Los, The Book of Urizen, The Book of Ahania, and The Book of Los); and two epic poems, Milton and Jerusalem. Other surviving works include various short lyrics, numerous fragments and drafts, a number of letters — and a third epic, Vala, later renamed The Four Zoas, which predates Milton and Jerusalem, and which became a source of lines and ideas for the latter poems. Blake worked and reworked Vala for years, but never made a final illuminated version of the poem; a complete, mostly-coherent version exists, but is clearly not a finished draft.

Broadly speaking, the illuminated works tell the story of the fall of the primeval Eternal Man, Albion, when his four primary faculties, the four zoas, began to struggle with each other for supremacy. His reason, Urizen, is typically said to have begun the fall, though Luvah, the passions, also has some guilt. To oversimplify greatly, the result of Urizen’s treason is his fall into a body created by Los — a version of the divine artist. Urizen himself creates the material world, the temporal universe. Within this world, Los, his wife (or ‘emanation’) Enitharmon, and their sons and daughters all struggle to do right as they undertand it. The first-born of Los and Enitharmon is Orc, the spirit of rebellion; the last-born, Satan, is the incarnation of Urizen in this world — at least in some texts; Jerusalem also says that Satan is the Spectre of Albion himself.

The early prophecies describe how Urizen creates repressive religion, monarchy, and the various systems of tyranny that oppress mankind. Orc arises to oppose him, a conflict which underlies the American and French Revolutions. Europe, the saga of the French Revolution, ends on a cliffhanger as Orc awakes and war impends:

The early prophecies describe how Urizen creates repressive religion, monarchy, and the various systems of tyranny that oppress mankind. Orc arises to oppose him, a conflict which underlies the American and French Revolutions. Europe, the saga of the French Revolution, ends on a cliffhanger as Orc awakes and war impends:

The sun glow’d fiery red!

The furious terrors flew around!

On golden chariots raging, with red wheels dropping with blood;

The Lions lash their wrathful tails!

The Tigers couch upon the prey & suck the ruddy tide:

And Enitharmon groans & cries in anguish and dismay.Then Los arose his head he reard in snaky thunders clad:

And with a cry that shook all nature to the utmost pole,

Call’d all his sons to the strife of blood.

In the long run, though, the French Revolution didn’t herald the imaginative apocalypse that Blake hoped for. His later epics seem to me to turn inward; although still very aware of the political circumstances around him, Blake’s work becomes more focussed on his personal state as prophet, and the experience of revelation. The restoration of Albion in Jerusalem, although cosmic in nature, feels to me less conditioned by outward events than the earlier prophecies.

One can argue the consistency of Blake’s revelation over the course of time, and how the continuity of his mythic system is to be understood. It’s certainly tempting to look at the corpus of his illuminated texts as a whole: “The Bible of Hell: which the world shall have whether they will or no,” as he says in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. But the Marriage was begun in 1790, America was engraved in 1793, and Jerusalem not engraved until 1820. Emphasis clearly shifts over time. Orc, rebellion, gives way as central character to his father, Los, the artist. (Note, incidentally, that Blake’s Orc has no etymological connection to Tolkien’s orcs; Tolkien went to a line in Beowulf for his monsters, while Blake’s Orc has a less certain derivation — the name may have come from orca, as Orc takes the form of a whale, or may derive from the Greek ‘orcus’ for hell, or, it has been said, may be an anagram of ‘cor,’ the Spanish for heart.)

One can argue the consistency of Blake’s revelation over the course of time, and how the continuity of his mythic system is to be understood. It’s certainly tempting to look at the corpus of his illuminated texts as a whole: “The Bible of Hell: which the world shall have whether they will or no,” as he says in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. But the Marriage was begun in 1790, America was engraved in 1793, and Jerusalem not engraved until 1820. Emphasis clearly shifts over time. Orc, rebellion, gives way as central character to his father, Los, the artist. (Note, incidentally, that Blake’s Orc has no etymological connection to Tolkien’s orcs; Tolkien went to a line in Beowulf for his monsters, while Blake’s Orc has a less certain derivation — the name may have come from orca, as Orc takes the form of a whale, or may derive from the Greek ‘orcus’ for hell, or, it has been said, may be an anagram of ‘cor,’ the Spanish for heart.)

I think the form of the poems seems to follow this philosophical shift. The importance of revolution fades over time; the internal apocalypse of art becomes more significant. In one reading, that could mean that the story, the myth, the fantasy, trumps direct resonance with external events. Similarly, Blake’s early fascination with contraries seems to give way to a more assured presentation of apocalypse. It’s as if his deeper immersion in his myth, or vision, or fantasy, allows him to progress as an artist; to more fully envision the redemption of humanity, of time and space.

Clearly, one cannot read Blake as one would a contemporary fantasy novel. His works aren’t novels, to start with. The epics in particular manipulate complex symbolism on multiple levels. Characters represent aspects of personality, but also places — Luvah, punished for attempting to usurp power, is symbolically similar to France after Napoleon.

Oddly, the more esoteric Blake’s symbolism becomes, in some ways the more familiar it seems. He imagines a complex interrelationship of emotional and spiritual states, reflected in both physical and metaphysical geography. Parts of this are very difficult; parts of it read like fantasy wordbuilding. I think here not so much of the detailed correspondences Blake finds between England and the Holy Land, but his imagining of Golgonooza, the fourfold city of art, as well as related lands: Bowlahoola and Allamanda, Lake Udan-Adan, the forest of Entuthon Benython.

Oddly, the more esoteric Blake’s symbolism becomes, in some ways the more familiar it seems. He imagines a complex interrelationship of emotional and spiritual states, reflected in both physical and metaphysical geography. Parts of this are very difficult; parts of it read like fantasy wordbuilding. I think here not so much of the detailed correspondences Blake finds between England and the Holy Land, but his imagining of Golgonooza, the fourfold city of art, as well as related lands: Bowlahoola and Allamanda, Lake Udan-Adan, the forest of Entuthon Benython.

Blake’s art is in a sense both fantastic and novelistic. He sees meaning in the concrete, in the minute particulars that make up the world. The real, the physical, are symbols to him of something greater. His attempt to express that greater meaning reads as fantasy, an argument that time and space have meaning beyond the material, that these things are an imaginative construction with a meaning deriving from that imagination. Again: is that fantasy?

I think so. I think Blake’s insistence on imagination is the key. Many religions would argue that the physical world is only an emblem of a greater meaning; but I think Blake’s work is distinctive, because it emphasises that the true meaning is an imaginative meaning. Personally, I associate that imagination with fantasy — broadly defined. As I say, Blake’s fantasy is clearly not ‘genre fantasy,’ whatever that may be. But it has fundamentally to do with the fantastic impulse, I think.

Los takes precedence over Orc: it is ultimately art, poetry, that gives meaning. It is the re-creation of things, going beyond the literal. It is the insistence on the world, not as it is, but as it is imagined; not the materialistic reality, but the primacy of art. The significance of Los is an argument for the importance of fantasy. It is a way for Blake to unite vision with reality.

Los takes precedence over Orc: it is ultimately art, poetry, that gives meaning. It is the re-creation of things, going beyond the literal. It is the insistence on the world, not as it is, but as it is imagined; not the materialistic reality, but the primacy of art. The significance of Los is an argument for the importance of fantasy. It is a way for Blake to unite vision with reality.

So, yes, I would argue that William Blake is a fantasist. And because we can look at him as a fantasist, we can see a new meaning for fantasy. A way to unite meaning to the world; a way to re-forge the world with imaginative meaning at its core. I think that in this, Blake is not just a fantasist, but arguably the primal fantastist, the writer whose total sense of imagination fuses the real and the fantastic, the visual and the written, in a way that writers and artists of the fantastic have perhaps been struggling to enunciate ever since.

To move forward sometimes involves looking back at the way we’ve come, to understand the path we’ve walked and the other choices we have. I think Blake represents a possible choice for fantasy, and suggests a way to articulate meaning in the form of the fantastic. His work may forever defy complete understanding. It certainly is not to every taste. But for some, for me, Blake’s epics and prophecies are among the greatest accomplishments of human art — and human fantasy.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Blake is profoundly Metaphysical.

‘Fantasy’ at it’s core is profoundly Metaphysical.

Yes ‘Blake’ + ‘The Pantheon of Fantasists’ are cousins.

Anything Metaphysical is cousin to speculative fiction + by extension fantasy.

For the record Blake is one of my favourite people. To date.

Including Blake as a fantasist seems like a fine idea, if we are then ready to include the large body of writers and artists who, as Blake sometimes did, attempt to render Christian themes in comprehensible yet inspiring ways through paint, chalk, and any number of other media. If we do open this door, let’s make sure that Goya walks in next (and not just to please Robert Hughes).

Good worth, Mr. Surridge!

markrigney –

Speaking for myself ( whom has similarly ‘odd’ opinions as Surridge ).

Blake is not a ‘Fantasist’ in the strict sense, but is a close relative.

Further my own worrying ‘Pantheon of Fantasits’ would probably probably knock you out.

PS. Goya pwns!

Tolkien argued that creating secondary worlds was more than just a privilege of humankind, as the being created in the image of a creator deity–“subcreation” was a sacred duty. Probably very few writers who write deliberately as fantasists see their work in such terms, but we can certainly consider Blake in that light.

Blake and Tolkien might not have been able to have a conversation, what with Tolkien’s ardent Catholicism and Blake’s ardent…Blakeanism. But their work obviously belongs in the same readerly conversation, in a way that would not be the case were we to substitute, say, Terry Brooks for either of them.

Probably I should give China Mieville another chance. His prose style is too florid for my taste, but the first thing I thought when I read review of The City & The City was, Oh, it’s the fourfold city of Golgonooza.

Loved this essay. Now I’m in danger of writing a about Hilda Doolittle as a fantasy writer.

RadiantAbyss: I think you’ve nailed something for me, actually; a realisation that I find metaphysical writing to be inherently fantastic. Or at least that I approach it the same way as I approach fantasy. I never really articulated that before. I can see the distinction you make between the two, but I’m going to have to ponder how I personally see the relationship. Thanks for something to think about!

markrigney: I’m all for Goya! I will say I sometimes find myself wondering whether something like Paradise Lost is better considered as fantasy or as historical fiction — was that how Milton would have approached it? But in the wake of RadiantAbyss’ comment, I’m thinking now that the literalised metaphysical makes it fantastic.

Sarah: Yeah, Tolkien and Blake make an interesting pairing. Tolkien didn’t have much imaginative sympathy with the Romantics in general, so far as I know, but he might well have had time for Blake; at least I can see how they might have been able to speak to each other. But you’re right, it’s much more a conversation their readers will have.

I’ve only read a couple of Mieville’s books; I thought they were okay, but didn’t grab me. I didn’t think of Golgonooza when I read The City & The City, though; the novel’s too anchored in the real, I suspect. That said, the prose didn’t seem at all florid to me, though neither did Perdido Street Station.

I’d be interested in seeing you write about Hilda Doolittle!

[…] been thinking over the past few days about last week’s post on William Blake and fantasy. I’ve come to realise that post is actually just the start of a much larger […]

[…] a while; I want to return to them now. The original inspiration for this series of posts came when I tried writing a piece on William Blake, and realised there was more to be said about Blake’s time and contemporaries than fit into the […]