Elf Opera in Tang China

Matthew Surridge’s fascinating post on specificity in setting got the various gears, levers, in pistons in my head working. I’m currently writing this in a cloud of steam gushing out both ears, and hopefully I’ll be able to finish before the gnomes who power the mechanisms of my consciousness go on strike.

The short version: Matthew, I agree completely. There is a certain charm to what I think of as the typical D&D setting, in which castles are built out of clichés mortared together with anachronisms, and the world is a playground of exotic sights for the mismatched band of adventurers to wander among and slay monsters in. It’s a lot of fun in a game–and sometimes fun in a D&D novel–but it lacks the kind of verisimilitude that makes a story really engrossing.

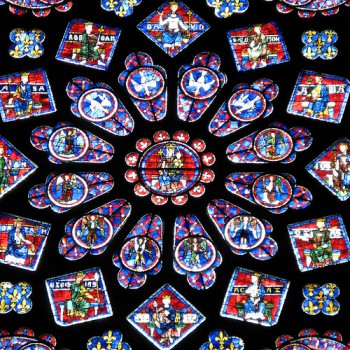

I tend to think that the richness of real-world Medieval civilization is masked by a series of misconceptions and broad generalizations, beginning with the tendency to see them as one long Dark Age spanning from the Fall of Rome to the Protestant Reformation. But the so-called Dark Ages were home to the kingdoms of Charlemagne and Alfred, the flourishing of Irish and Italian monasticism, and the first sparks of the most vibrant intellectual life the world had yet seen. Likewise, the High Middle Ages were an age of soaring cathedrals, vibrant art and music, and universities that studied everything from Roman law to medicine.

At the same time, the European Middle Ages were anything but homogenous. The time period covers over a thousand years, which contain literally hundreds of distinct peoples and cultures. The Vikings who besieged Paris later became the Normans who conquered England and ruled Sicily. The balance between monarchs, emperor, and papacy was constantly shifting, sometimes responding to new threats or influences, as when the Mongols crashed against the armies of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Suffice to say, I tend to think that readers who complain about the banality of Medieval or European-flavored settings in fantasy have been cheated. What they’ve been delivered is watered-down and rendered into a kind of generic Fantasyland, the setting for stories that John C. Wright calls “Elf Opera“. I don’t want to sound as though I’m smearing D&D, but the generic D&D setting has very little to do with Europe or the historical Middle Ages. I’ve always thought that, when readers express a desire for new settings, they’re expressing more accurately a desire for authenticity and verisimilitude. Half-orcs and elves throwing magic missiles wouldn’t instantly become more exciting if you called them “samurai” and “miko” instead of “warrior” and “wizard”.

Fantasy involves, well, fantasy, but our fantasies are built on concrete things, among them knowledge of our world as it has been. Depth of knowledge and understanding, I would argue, is more important than a shallow exoticism. An author who truly understands the worldviews and people of 11th century England is, to my mind, more likely to write a gripping novel than one who is just mining East Asia for exotic synonyms to “vampire” and “paladin”.

This may be why so much of my reading lately has been historical fantasy rather than full secondary world fantasy (see my gushing review of Twelve): Because the authors of these novels have usually made at least some effort to truly understand an alien culture and worldview, and their books can’t help but be richer as a result. They’ve sought to understand what life really was in 8th century Baghdad or feudal Japan or Czarist Russia, and on that foundation of juicy cake they’ve spread a tangy frosting of sorcery, monsters, and high adventure. It’s a two-hit combo of escapism and wonder.

I personally write mostly secondary world fantasy, but I try to avoid generic settings and vague Fantasylands whenever possible. In my Shabak stories and novel, I try to portray a culture inspired by the Dark Ages of northern Europe, a time when a lord had a warband instead of a retinue of knights, when blood oaths were prized higher than lofty ideal s of chivalry, and new religions warred with old. I mix plenty of fantasy in–the shadow magic, crab-men, and primeval monsters are dead give-away–but I think the historical atmospheres and cultures I’ve drawn on ultimately make the material stronger.

s of chivalry, and new religions warred with old. I mix plenty of fantasy in–the shadow magic, crab-men, and primeval monsters are dead give-away–but I think the historical atmospheres and cultures I’ve drawn on ultimately make the material stronger.

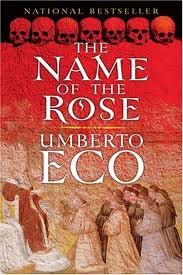

Final note: The finest novels I’ve read with a Medieval European setting are Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose and Baudolino, both of which are historical fiction rather than fantasy (well, Baudilino is arguable). Both do a spectacular job of capturing the Medieval mind in all its color, complexity, and wonder. I recommend them highly.

I don’t exactly agree with both arguments. For me, it is an issue of writing ability rather than verisimilitude. If the writing, the vision, is excellent, then it doesn’t matter whether the setting is historical, an Earth historical period transported to a secondary world, or a crazy stew of periods and influences. Take Mieville’s Bas-Lag series, Howard’s Hyborian Age, Morgan’s The Steel Remains, Kishimoto’s Naruto, Mashima’s Fairy Tail, and Tolkien’s Middle Earth. All of those works marry various periods and cultures into excellently done and believable worlds.

I definitely agree there is a huge problem of versimilitude in Medieval Fantasyland. One reason I first conceived of Summa Elvetica: A Casuistry of the Elvish Controversy was to attempt providing an artistic corrective to the ignorant portrayal of the medieval period as a secular, post-modern time, stocked primarily with proto-atheists, proto-feminists, proto-liberals, proto-environmentalists, and a few cardboard cutouts who oppose them because they are Pure Evil.

The main problem, as I see it, is that the anti-religious bias of many modern fantasy authors rebels against providing an even remotely realistic portrayal of a time and place where the Church is both popular and the most powerful international institution. But you simply cannot throw out that very important aspect of the time and place and hope to end up with anything that is convincingly medieval.

There are exceptions, of course. Judith Tarr, Guy Gavriel Kay, and Katherine Kurtz all present fantasy lands that are actually medieval in feel and effect. George R.R. Martin did a particularly elegant job with his “sparrows” in A Song of Ice and Fire.

One needn’t be religious oneself to write realistically and well about medieval religion any more than one must be a weapons technician in order to properly describe the use of an AK-47. But to write fantasy festooned with medieval trappings that lack strong religious elements is about as convincing as serious military fiction in which all the guns are branches gathered from special trees that have magic exploding projectiles flying out of them for no apparent reason. A sufficiently talented writer may be able to make such absurdities entertaining, but cannot make them any less intrinsically stupid, nonsensical, and ahistorical. One may thoroughly enjoy Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s series, but only if one refuses to take his Bistromathematics or Improbability Drive physics seriously.

Any setting involving humans that doesn’t account for religion completely lacks credibility. The problem specifically with historical fiction is that, here in the English speaking world, we have been taught the Protestant version of history, which seeks to minimize the impressive achievements of the Middle Ages. Secularists denigrate the period for similar reasons. The irony is that Middle Age achievements in art, philosophy, architecture, and many other fields surpass anything we see produced today, despite the superior technology of the 21st Century.

What? Are you seriously going to insist that Michelangelo was a better painter than Andy Warhol or Thomas Kincaid? That Thomas Aquinas was a better philosopher than Richard Dawkins?

Surely you jest!

Michelangelo is Italian Renaissance. For the best in contemporary art, watch PBS’s Art 21. Thomas Kincaid is crap. And Dawkins is a biologist, not a philosopher. Compare Satre, Derrida, Heidegger,Gramsci, etc. to Aquinas.

Correction, Dawkins is a biologist who thinks he is a philosopher. I don’t know enough Heidigger to have an opinion on him, but Sartre, Derrida, and Gramsci don’t fare well in comparison with the Great Ox.

Although Gramsci was certainly one hell of a political tactician, one must give him that.

Touche on Dawkins (Hitchens is more readable anyway). I do wonder, though, exactly how the periods work- when is the medieval period being compared to exactly?

I do agree that there are some subjects, religion included, that are really difficult for some fantasy writers to deal with.

Verisimilitude is nice, but in cases like this it can seem like a club wielded to chastise others and shove them inline with the wielder’s thinking and definition of what should be proper. It’s a good catch-word to charge up like-minded folk into agreeing with each other, little different than us-them political rhetoric.

Seems like this post has several different arguments within it. I wouldn’t mind seeing Sean Stiennon expand each idea into its own post to elaborate further. One point is lack of historical authenticity in fantasy (or shouldn’t that hold mostly for works actually labeled historical fantasy?). Another related point is common stereotyping of the medieval period. A third seems to be criticizing stories/settings that poach East Asian or other exotic motifs for gain and profit. I’m not up-to-date on many trends in the fantasy genre, but I haven’t seen this happening with any frequency.

Naming examples would help. Arguments that make generalizations about entire sub-genres without naming names fall a bit flat. For instance, what do you mean by typical D&D setting? The generic setting assumed in the core rules or one of their published campaign settings? D&D hasn’t published a Far East inspired setting in a decade which was adapted from another company’s IP which they owned at the time. Before that, we have to look back at the mid-late ‘80s. Besides, it would be more accurate to say D&D is modeled more on fantasy fiction than any historical periods (look up Appendix N).

I wanted to agree with the argument in the original post, but the more I think about it, the more I find it indefensible. The beating-horse characterization of D&D is itself a stereotype at least as unfair as the stereotyping of the Middle Ages.

Well said, Henry.

I’m happy to hear my post struck a nerve with you, Sean! I thoroughly agree with what you’re saying about having an understanding of historical cultures, as opposed to using culture as a gloss. I’d be really interested in hearing what sort of works you use as references for your Dark Ages writing — I’ve been trying to read up on the history of Europe between about 1000 and 1200 for the serial I’m writing (The Fell Gard Codices), but I’ve been finding that so much of at least the easily accessible work on the Middle Ages seems to look more at the 14th century.

sftheory: I take your point, but the examples of yours that I’m familiar with (Howard and Tolkien) were I think writing from a sense of specificity — they combined cultures, and extrapolated to what might have been. That’s as opposed to relying on general stereotypes about previous eras. I understand Sean as making the general point that the vision will call forth a specific sense of a culture — whether based on historical research, or a writer’s playing with history, or a writer building his own immersive world. That is, shallow writing relies on gloss; ‘samurai’ and ‘miko’ for ‘warrior’ and ‘wizard.’ Good writing goes beyond that, to give a sense of depth to the setting.

(How is Morgan’s fantasy, by the way?)

Theo: I agree with your general point, but I think it extends to more than the medieval Catholic Church — the European Middle Ages includes Norse pagans, Muslims in Spain, the Eastern Church, and so on. That is, as Tyr says, it seems to me to be a question of religion in general, and accurately portraying the religion appropriate to a given culture. And also realising how what we now call ‘religion’ was linked to one’s understanding of how the everyday world worked.

Then again, medieval Catholic societies were influenced not only by the religion of the Church, but to some extent by the Church structure itself. I read an interesting argument not long ago (I don’t know how widely accepted it is) that the feudal system took the form it did as a secular counterpart to the Church hierarchy — that the Church provided the model for the secular social structure.

Henry: I took Sean’s post to be a complaint about a general lack of depth in setting. That is, a complaint about settings where stereotypes took the place of thought-through writing. Not to speak for him, but I think his comment about D&D didn’t have to do with Asian setting, but the ‘typical’ setting — Greyhawk, the Forgotten Realms, places like that.

I enjoy D&D as a game, myself, but I do find it’s not got a lot to do with history. It is very true that Appendix N of the old DMG shows the sources of the game, but … in a way, that’s the problem. The game risks becoming a photocopy of a photocopy. The original writers generally paid attention to the sources of their own settings — to the history, and historical writings, that inspired them. To the extent the game pays attention to the fiction based on the history, and not the history itself, the history risks becoming stereotype.

(It is also true that some of the Appendix N writers didn’t care much for verisimilitude of setting. But mostly I think that’s because they were fairy consciously replacing verisimilitude with irony. Moorcock was interested in telling an adventure tale, so he cared about plot and not verisimilitude, even if that risked weakening his stories. Dunsany and Bellairs were, to me, ironists who consciously played with the effects of contrasting modern sensibilities and anachronisms with traditional settings. Or at least that’s my take.)

Matthew: Granted default D&D contains many stereotypes, in part because the game’s rules system places everything into codified classes and abilities and also because one selling point is to emulate the feel of its fictional inspirations. Settings published for a system have to deal with providing locales and cultures catering to every one of those standardized roles. Despite the need to conform to genre and gaming expectations and to publisher requirements, specific settings is where I think D&D actually fares better against labels of stereotype fantasy.

I would argue the prominent settings succeed at creating a sense of depth or culture more than they fail. While parts of these settings do offer the same shallow fantasy stereotypes, many diverge, subsume, or outright buck the cliches. The implications of embracing or avoiding certain D&D standards are not often glossed over, many are handled as deliberate design choices with the proper affect on the setting. Many settings have instead adapted the rules to the setting rather than the other way around.

Some of the setting books read like detailed travel guides, some even like ethnographies with extensive entries on the outlooks and attitudes of races, ethnicities, and cultures. Some settings also include information like trade routes and the imports/exports of regions, local coinage, clothing, customs and names for deities, the specialty brews and foods of local establishments. There are criss-cross networks of relationships, alliances, intrigues, and biases between nations and cultures, showing at least an attempt at a living world. Some of these settings depart significantly from the D&D norm, with appropriate adjustments to the cultures and perspectives of the peoples. None of these tidbits truly matter in a typical bash-the-monster game, but they are integral components of a typical setting.

The quality of information needed to reach a threshold to fictional immersion is a personal measure. Even if you don’t see a skilled realization of setting depth, you should be able to notice an attempt at such. If you have the time and inclination, perhaps take a look at some of them again while keeping in mind what I’ve said above.

If settings that lean closer to historical fantasy are your preferences, several D&D settings have a strong historical basis. In various editions there were setting books that offered fantasy adaptions of specific historical periods that adhere closer to their real world inspirations. I found many of them to be worthwhile both as D&D settings and (keeping in mind these are not academic or literary explorations on the period) for cultural/historical details and immersion.

Some settings instead seem like real world areas with the names changed slightly, events rearranged, and with a dash of magic added. I’ve always found them to be the least inspiring, neither truly historical fantasy or fully embracing secondary world fantasy. I feel D&D’s original attempt at an East Asian setting fell into this lackluster middling category. It’s why I feel the title of the original post is not necessarily a bad thing.

I’ll cop to not having followed the development of the older settings, and how that may have changed over time. And certainly D&D works for its main purpose — to create settings in which a group of moderns can comfortably play an adventure game. In a way, that’s my argument; because D&D is meant as a game, and a game for people who don’t have to know a lot about the middle ages, the default version of the game gives you some medieval aspects (say, a hierarchical and somewhat feudal social structure, an elevated level of violence throughout society, large unexplored and underdeveloped areas, a pre-modern-firearms level of technology) that don’t always seem to fit with some of the things that make for a viable playing experience (widespread societal use of magic, easy social mobility, cities with massive populations, magic items and bejeweled treasures in massive quantities).

That said, I can see what you mean about some settings playing against the D&D norm — I think Eberron works because it pushes ‘magic as technology’ so far, and creates a pulp-noir-industrial-fantasy that’s some distance from anything that really feels medieval. Sometimes, also, the genre mix is fine; I felt the original Ravenloft boxed set did a great job of capturing the feel of original gothic horror, while playing about with stereotypes of the gothic era, and pushing its ‘period’ up to, in some cases, the late 19th century.

What were the names of the historical-setting books? I’d be interested in checking those out.

Your point is kind of my point as well. D&D has its own purpose and the game, fiction, and settings serves that purpose. The fault of stereotype shouldn’t fall on D&D because the game mostly picked up on some common archetypes in fantasy fiction. Not to say the sources of inspiration were stereotypes, the game just uses some common points the designers through interesting and codified them into their own interpretation. Though there are some peculiarities specific to D&D that do not and have never existed in the fantasy literature it draws inspiration from.

Fantasy fiction that hews too closely to the game are another matter and reflect more on the author (or perhaps the fantasy audience) than any problem with the game or its supposedly stereotyping affect on the genre. In a way, the Elf Operas/Fantasyland (I’ll throw a spontaneous term into the list: McMedieval) generic fantasy works are a stereotype of D&D.

It’s nothing to worry about, for many D&D is their first introduction to fantasy. Now video games and MMOs have the same role. Those are a reinterpretation of RPGs like D&D but in electronic form, they are yet another derivative removed from the original source. I’m a bit tickled people remember to pick on D&D and haven’t already moved on to Warcraft as the new standard of derivative fantasy.

With the more distinct D&D settings, their redressing of D&D to fit the setting is readily apparent. I think they are all well done and interesting each in their own way. I think that carries through to even the more standard, ‘stereotype’ settings. Of course, as a fan of the more generic settings I am biased. I believe few if any of them claim to be strongly medieval. Greyhawk came before my time entering into the hobby, so I will leave analysis of that setting to a knowledgeable fan of that setting.

Forgotten Realms is an interesting case as its long active publication history, development across several editions by many different designers, and sheer volume of information makes it harder to define. There are medieval elements, but the central, default areas always struck me as more Renaissance with wizards replacing the role of talented individuals. In that period there were great wealthy cities and civilizations with some little explored unknown places. Magic use is taken into account (i.e. some cities depend on magical aid in agriculture to support their large populations per farming area), but it is not seen as technology like we do today but as art (much the same way DaVinci was a polymath artist, engineer, inventor, etc.). Magic is called the Art in the setting. Still it doesn’t model itself strongly on the time period and doesn’t claim to. I think it works as well as other settings, gaming or literary, of this type and purpose.

The historical adaptations I remember fondly belong to the HR series (Historical Reference) during D&D 2nd Edition. They were green perfect bound books.

HR1: Vikings

HR2: Charlemagne’s Paladins

HR3: Celts

HR4: A Mighty Fortress

HR5: The Glory of Rome

HR6: Age of Heroes

HR7: The Crusades

More recently the Mythic Vistas series by Green Ronin Publishing have garnered positive reviews. I have several of the books myself. They include (but include also some modern eras, and oddly enough an adaptation of the Black Company novels):

Egyptian Adventures: Hamunaptra

Eternal Rome

Medieval Player’s Manual

Testament: Roleplaying in the Biblical Era

The Trojan War

Expeditious Retreat Press published a series called A Magical Society which are more like guides on how to merge historical eras with magic and the effect such would have on society and economics. With the great number companies arising due to the Open Gaming License, there are no doubt many more offerings in historical fantasy gaming.