The Asgardian Adventures of Zelenetz and Vess: The Raven Banner and The Warriors Three Saga

Marvel Comics has published some great works over the nearly fifty years since the company took its modern form with Fantastic Four #1. One thinks of the suberb superhero comics of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, but there’s a lot more than that in Marvel’s vaults. William Patrick Maynard’s done some strong work on this web site looking back at some excellent series, and I encourage everyone to take a look at his current posts on Tomb of Dracula, perhaps my own favourite Marvel book of the last forty years.

Marvel Comics has published some great works over the nearly fifty years since the company took its modern form with Fantastic Four #1. One thinks of the suberb superhero comics of Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, but there’s a lot more than that in Marvel’s vaults. William Patrick Maynard’s done some strong work on this web site looking back at some excellent series, and I encourage everyone to take a look at his current posts on Tomb of Dracula, perhaps my own favourite Marvel book of the last forty years.

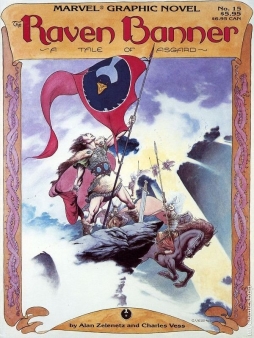

You can find Tomb of Dracula, like most Marvel books, in several reprint collections. But at least one of the best things ever published by Marvel isn’t currently available in any form. First printed in 1985, as part of Marvel’s early “Graphic Novel” line — actually a series of softcover graphic albums, about sixty pages each — The Raven Banner, written by Alan Zelenetz, with art, colouring, and design by Charles Vess, is a brilliant work of fantasy. The book unites a strong sense of myth, a deft touch in plotting, and highly impressive visuals to tell “A Tale of Asgard” (as its subtitle proclaims); and a powerful tale it is, filled with wonder and sorrow.

The Raven Banner is the story of Greyval Grimson, heir to a family entrusted with one of the greatest magical items possessed by the gods of Asgard, the Raven Banner of the title. When unfurled during a battle, the banner will grant victory to the army which holds it — at the cost of the life of the banner’s holder. The book opens with one such battle, in which Greyval’s father dies; but Greyval, we find, has been enticed under the earth by trolls, mischievous masters of illusion allied to the giants. Greyval feasts and drinks among the trolls while the battle plays out above, at which point the trolls let Greyval go, believing a prophet who says that Greyval will kneel before them till the end of time. Above ground, Greyval marries his love, a valkyrie named Sygnet; but when he finds that the banner’s been lost, he realises it is his duty to retrieve it. Only, as an Asgardian, Greyval need never die. So will he give up his immortality for the sake of the banner? What is the value of duty? What is more important: the joys of life, or a glorious destiny?

Imagine Conan in Shadizar, meeting with a beautiful woman calling herself Fortuna who pays him to find Thuris, the man who kidnapped her younger sister. Conan accepts the woman’s coin but finds himself in the middle of double and triple crosses as Fortuna — known as Brigid the Bold in the underworld — seeks for the Falcon of Maltus along with her betrayed confederates, Jubliex Cairo, Wilmer the Younger, and Gutmar.

Imagine Conan in Shadizar, meeting with a beautiful woman calling herself Fortuna who pays him to find Thuris, the man who kidnapped her younger sister. Conan accepts the woman’s coin but finds himself in the middle of double and triple crosses as Fortuna — known as Brigid the Bold in the underworld — seeks for the Falcon of Maltus along with her betrayed confederates, Jubliex Cairo, Wilmer the Younger, and Gutmar.  As usual, the kind of stories I was reading and writing bled into the kind of games I was playing, and this took me down a path I did not expect. I ended cobbling together a system that was purpose built to play “sword noir.” In order to do that, I had to define the term.

As usual, the kind of stories I was reading and writing bled into the kind of games I was playing, and this took me down a path I did not expect. I ended cobbling together a system that was purpose built to play “sword noir.” In order to do that, I had to define the term.

Twelve

Twelve The Tiger’s Wife is an interlocking series of fabulist tales, set in an unnamed Balkan country that is obviously Yugoslavia before and after its dissolution into ethnic political states, which unfolds the life and death of the narrator’s grandfather. It’s a meditation on grief, cultural blindness and bigotry, among other things, but overarchingly the constant effort to try to live a decent life and see the decency in others, even those who seemingly don’t possess it. Written by Téa Obreht, whom The New Yorker named one of the twenty best American fiction writers under forty and the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” list, it is, as you might expect given those accolades, considered a “literary” novel. Which is perhaps why you haven’t seen much mention of it in genre circles, despite the fact that it is a fantasy. However you want to classify it, it’s good and well-deserving of the hype it’s received. One thing that struck me that I don’t think I’ve seen mentioned is the similarity between Obreht and Ray Bradbury in his prime, back in the days when Clifton Fadiman was trying to sell The Martian Chronicles to the literary mainstream.

The Tiger’s Wife is an interlocking series of fabulist tales, set in an unnamed Balkan country that is obviously Yugoslavia before and after its dissolution into ethnic political states, which unfolds the life and death of the narrator’s grandfather. It’s a meditation on grief, cultural blindness and bigotry, among other things, but overarchingly the constant effort to try to live a decent life and see the decency in others, even those who seemingly don’t possess it. Written by Téa Obreht, whom The New Yorker named one of the twenty best American fiction writers under forty and the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” list, it is, as you might expect given those accolades, considered a “literary” novel. Which is perhaps why you haven’t seen much mention of it in genre circles, despite the fact that it is a fantasy. However you want to classify it, it’s good and well-deserving of the hype it’s received. One thing that struck me that I don’t think I’ve seen mentioned is the similarity between Obreht and Ray Bradbury in his prime, back in the days when Clifton Fadiman was trying to sell The Martian Chronicles to the literary mainstream.