Steve Ditko and The Start of Something Strange

One of my favourite Marvel Comics characters, certainly my favourite of all their big names, is Doctor Strange. Like most established Marvel characters, he’s been handled a lot of different ways over the course of time. I’d like to look back, and look closely, at one of the early tales that defined him most clearly — specifically, his origin story.

One of my favourite Marvel Comics characters, certainly my favourite of all their big names, is Doctor Strange. Like most established Marvel characters, he’s been handled a lot of different ways over the course of time. I’d like to look back, and look closely, at one of the early tales that defined him most clearly — specifically, his origin story.

Doctor Strange first appeared in Strange Tales 110, in which he investigates a man’s recurring bad dreams and battles an old enemy, Nightmare, master of the Dream Dimension. Strange is a kind of occult detective, a figure in the tradition of Martin Hessselius or John Silence (or, more closely, Mandrake or Zatara). Unlike them, though, he’s more magician than detective. Although we meet him here for the first time, he’s clearly an experienced wizard — “Never again shall you thwart me!” claims Nightmare. We don’t discover in this five-page story how Strange came to have his powerful magical amulet, or who his mysterious mentor is.

The next month’s story gives us a bit more background, introducing another archenemy who has a history with the good doctor — Baron Mordo, a former student of Strange’s mentor and master. We get a sense of Strange’s power, too, as he has a battle of astral forms with Mordo. The next two issues didn’t have a Doctor Strange story, then issue 114 presented another battle with Mordo. It was with the next story, in issue 115, that we finally learned who this man of mystery really was.

Before diving into that tale, a few words of background and context are worth mentioning. To begin with, let’s look at the issue of who should get credit for the story. Officially, these early tales were written by Stan Lee, with art by Steve Ditko, and lettering by Terry Szenics for the first two stories, then by Sam Rosen, who would go on to alternate lettering duties with Art Simek for the rest of Ditko’s run on the book. I can’t find any information on who did the original colouring work.

Before diving into that tale, a few words of background and context are worth mentioning. To begin with, let’s look at the issue of who should get credit for the story. Officially, these early tales were written by Stan Lee, with art by Steve Ditko, and lettering by Terry Szenics for the first two stories, then by Sam Rosen, who would go on to alternate lettering duties with Art Simek for the rest of Ditko’s run on the book. I can’t find any information on who did the original colouring work.

Having said all this, though, it’s important to realise that the art/story breakdown is not as simple as it seems. Lee and Ditko worked “Marvel-style,” meaning that in lieu of a full script breaking down the story panel-by-panel, Lee would give Ditko a loose outline. That might be a page-by-page synopsis, or it might be much less. Ditko would then draw the book, pacing it and structuring it as made sense to him. Lee would then provide dialogue and captions over the finished art.

That process has led to much debate over who was really the writer for any given book. How detailed was the synopisis? How much did the artist bring to the plot? Lee’s been quoted as saying that he sometimes gave Ditko only a one-line idea, which Ditko would turn into a complete story. In fact, later in Ditko’s run on Strange Tales, starting with issue 141, Ditko actually was given credit for “plot.”

I suspect that Ditko was the plotter, effectively the guiding creative spirit of the book, from far earlier than that. I think that if you compare Ditko’s collaborations with Lee, particularly their Doctor Strange and Spider-Man work, with Lee’s other writing of the time, you find much neater plotting in the Ditko tales (and we’ll see some of that in Strange’s origin story). The Kirby/Lee comics in particular had their own virtues — a mastery of energy, a headlong adrenaline rush captured on paper — but Ditko crafted tight, perfectly-constructed tales that also seemed to build in a very distinctive way.

I suspect that Ditko was the plotter, effectively the guiding creative spirit of the book, from far earlier than that. I think that if you compare Ditko’s collaborations with Lee, particularly their Doctor Strange and Spider-Man work, with Lee’s other writing of the time, you find much neater plotting in the Ditko tales (and we’ll see some of that in Strange’s origin story). The Kirby/Lee comics in particular had their own virtues — a mastery of energy, a headlong adrenaline rush captured on paper — but Ditko crafted tight, perfectly-constructed tales that also seemed to build in a very distinctive way.

In fact, a few years ago comics writer Steven Grant wrote an excellent, and highly persuasive, column arguing that Ditko’s Doctor Strange was one of the first American graphic novels. As Grant points out, Ditko’s run, which extended up through Strange Tales 146, is bound together both by a sophisticated serial plot and also an ongoing theme: the development of Stephen Strange as a man and a hero. It looks like Ditko had an overall idea in mind for the comic (it certainly seems to me that you can see a lot of the later development of the book, one of the absolute highlights of the Silver Age of comics, implied in Strange’s origin story). So I tend to consider Ditko as the prime creator of Doctor Strange, the writer in all but name.

Certainly the introduction of Strange as a character seemed surprisingly neatly done for early Marvel. The piece-by-piece development of Strange’s milieu and history whets the appetite for the backstory that will explain who he is and how he came to be the wizard we’ve met. Practically, it looks like Lee (or someone above him) wasn’t sure of the commercial viability of the character; he gets a two-issue tryout, then nothing for two months, then another five-page story before his origin is given in a larger eight-page tale. By that time presumably Marvel had sales figures and some sort of audience response to the Doctor Strange character. I don’t know whether this led them to give the green light to an origin story, but it wouldn’t surprise me.

Before I describe the story in brief, take a moment to consider the challenges this tale had to meet. Firstly, it had to live up to the hints and references we’d had in the previous Strange stories. Secondly, it had to fit the character, and preserve his air of the unknown while also filling in all that readers needed to know about him — it had to give his background while also maintaining him as a figure of mystery. And, of course, it also had to establish him as a viable serial character, who could serve as a lead through any number of tales.

Before I describe the story in brief, take a moment to consider the challenges this tale had to meet. Firstly, it had to live up to the hints and references we’d had in the previous Strange stories. Secondly, it had to fit the character, and preserve his air of the unknown while also filling in all that readers needed to know about him — it had to give his background while also maintaining him as a figure of mystery. And, of course, it also had to establish him as a viable serial character, who could serve as a lead through any number of tales.

Whoever it was who plotted the origin story, they came through in spades.

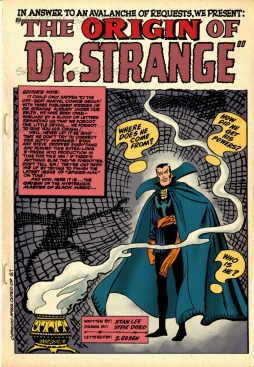

It begins with a splash page, at the top of which readers are told “In answer to an avalanche of requests, we present: ‘The Origin of Doctor Strange’”. Strange stands below, surrounded by question-mark-shaped captions that look a lot like Ditko’s lettering designs, and which seem to have little relation to Lee’s ‘Editor’s Note’ off to the side. “Where does he come from?” “How did he get his powers?” “Who is he?”

The story proper then starts in India, as “a haggard figure” enters what appears to be a temple, confronts an old man called the Ancient One, and demands to be healed of an unspecified injury. The Ancient One says he will heal only someone who is worthy, and when the intruder makes a move against him, lifts the man into the air with a wave of his hand. The Ancient One uses magic to examine the intruder’s memory: he turns out to be an American named Stephen Strange, a proud and heartless doctor who had cared only for success — until a car crash left him with nerve damage, preventing him from ever operating again. Strange fell into a spiral of self-pity and became a drifter, until he heard a rumour of a figure called the Ancient One, who could cure anything.

The Ancient One tells Strange again he will heal only the worthy, and invites Strange to study with him: “I seem to see a spark within you … a spark of decency … of goodness … which I might be able to fan into a flame!” Strange refuses, and calls him a fraud; but can’t leave, as heavy snows have sprung up around the Ancient One’s mountain retreat. Strange meets the Ancient One’s pupil, Baron Mordo, but is still soon at loose ends, as Mordo is entirely dedicated to magic and study. Then Strange sees the Ancient One attacked by a spell, which the old man barely turns aside. Strange finds himself beginning to wonder about the reality of magic — and then stumbles on Mordo, trying to cast another wicked spell against the Ancient One.

The Ancient One tells Strange again he will heal only the worthy, and invites Strange to study with him: “I seem to see a spark within you … a spark of decency … of goodness … which I might be able to fan into a flame!” Strange refuses, and calls him a fraud; but can’t leave, as heavy snows have sprung up around the Ancient One’s mountain retreat. Strange meets the Ancient One’s pupil, Baron Mordo, but is still soon at loose ends, as Mordo is entirely dedicated to magic and study. Then Strange sees the Ancient One attacked by a spell, which the old man barely turns aside. Strange finds himself beginning to wonder about the reality of magic — and then stumbles on Mordo, trying to cast another wicked spell against the Ancient One.

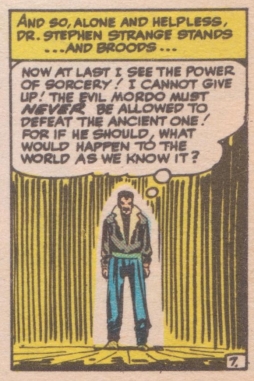

Mordo readily admits he wants to kill his master, but curses Strange so that he cannot speak of what he’s learned or physically attack Mordo. Strange tries to warn the Ancient One nevertheless, but finds he cannot. Mordo mocks his helplessness, and Strange broods on what has happened: “Now at last I see the power of sorcery!” he thinks. “I cannot give up! The evil Mordo must never be allowed to defeat the Ancient One! For if he should, what would happen to the world as we know it?”

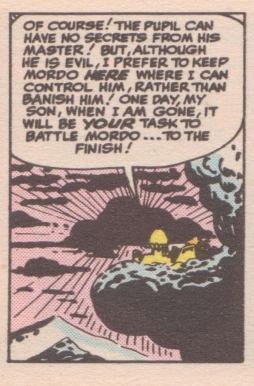

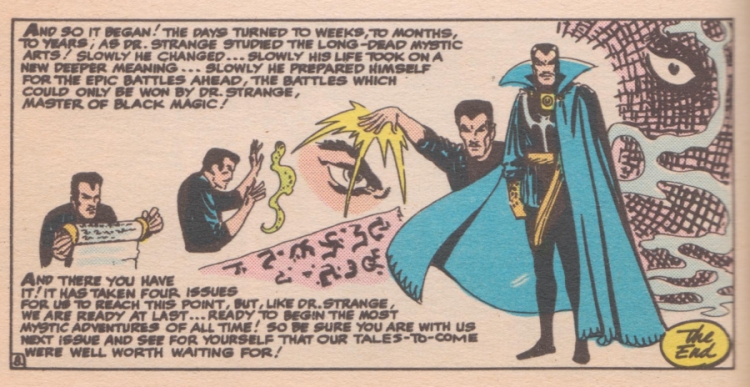

Strange realises he can’t speak to the Ancient One about Mordo — but can speak of other things. He approaches the Ancient One, and asks to become his pupil. The Ancient One agrees, and dispels Mordo’s curse. He knows of Mordo’s treachery, he explains, but prefers “to keep Mordo here where I can control him, rather than banish him! One day, my son, when I am gone, it will be your task to battle Mordo … to the finish!” Strange reaffirms his desire to learn magic, and the story ends with a long panel showing his training and gradual transformation into the cloaked mage we’ve seen in previous chapters.

It’s a tight plot, and a great origin story. It does everything it needs to do, paying off the hints we’d seen in previous chapters, and establishing Strange as a powerful figure deeply concerned with righteousness and with protecting the world from mysterious dark forces beyond. It works narratively in large part, I think, due to Ditko’s mastery of comics storytelling.

It’s a tight plot, and a great origin story. It does everything it needs to do, paying off the hints we’d seen in previous chapters, and establishing Strange as a powerful figure deeply concerned with righteousness and with protecting the world from mysterious dark forces beyond. It works narratively in large part, I think, due to Ditko’s mastery of comics storytelling.

After the splash page, the entire story is told in pages composed of nine-panel grids — except when Strange stumbles on Mordo casting a spell, and the point where Strange tries to tell the Ancient One about Mordo, when in both cases a tier of three panels are replaced by a tier of two panels; and the story’s concluding long panel, which takes up what would be the last three-panel tier. The story beats Ditko chooses to highlight are reasonable enough, crucial points where magic moves to the fore, and where a specifically visual moment or moments could use a little room to breathe. They also give some variation to the page layouts without breaking the mood.

In fact, Ditko uses the grid very effectively to create a sense of closeness, of confinement, echoing Strange’s unwilling stay in the mountain sanctum. Ditko’s art is by nature expressionistic (perhaps more in the film tradition than the painting style), but here he manipulates a difficult storytelling technique, the repetitive claustrophobic nine-panel grid, and makes it work. Practically, it allows him to fit more story beats onto a page, deepening the narrative, but it also sets mood and pace. By varying his camera angles, he keeps the grid from feeling static, an easy trap to fall into; in fact Ditko shows off here an admirable sense of panel composition and panel-to-panel transition.

Graphically, that makes for a very varied set of panels. The story’s full of close-ups, particularly during Strange’s flashback sequence. In part that’s one solution to the challenge of how to work with the small panels of the grid. But Ditko throws in a goodly number of long shots, as well, and has an excellent sense of how to work in backgrounds to create a sense of concrete three-dimensional place.

Graphically, that makes for a very varied set of panels. The story’s full of close-ups, particularly during Strange’s flashback sequence. In part that’s one solution to the challenge of how to work with the small panels of the grid. But Ditko throws in a goodly number of long shots, as well, and has an excellent sense of how to work in backgrounds to create a sense of concrete three-dimensional place.

Notably, there’s a recurring graphic motif that Ditko uses in the backgrounds of the Ancient One’s sanctum, a kind of distorted tic-tac-toe grid in a circle. We’ve seen it in Strange’s house in previous chapters, as a frame in a distinctive round window. It turns up a lot here: firstly on page four, panel three, as a shadow behind Strange and the Ancient One; then in the next panel, as a window-frame through which Strange notices the snow’s moved in; then again in panel seven, above a studying Baron Mordo; then a bit in the panel after that, as the Ancient One seems to face Mordo across the panel border; then in the middle panel of the next page, as Strange again looks out a window and broods; then, on panel one of page seven, in an unexpected reversal, we’re outside the window, looking in at the small figure of Strange cursed by Mordo, his face in shadow; then, finally, in panel six of the last page, the last panel of the story proper, as Strange accepts his place as a magician.

The image helps tie the story together by its recurrence. It also gives character to the Ancient One’s sanctum; it’s a distinctive, unsettling shape. Ditko uses it for great expressionist purpose — most dramatically on the page seven shot, when it gives the distinct sense of imprisoning Strange. But the fact it turns up in the last panel suggests another way to think about it: a symbol of magic, terrifying when not understood, but when approached properly, a gateway to something greater.

Ditko’s got a great sense of visual symbolism in general, which he conveys with subtlety and economy. Panel 5 of page 4 shows us the sanctum from the outside, on an isolated mountain cliff, snowed in, with deep cloud behind it; Panel 5 of page 8, the exact same spot on the page, gives us a view of the sanctum under bright sun, the clouds gone, only a single black cloud right in front of the sun’s face. Where the page 4 panel gives us dialogue of Strange scoffing at magic, the dialogue on page 8 is the Ancient One explaining that he knows Mordo is evil but is keeping him close for his own purposes — the cloud in front of the sun, as it were. Note that the cut to the exterior shot here isn’t something directly relevant to the dialogue; it’s a simple visual way of showing how the Ancient One has dismissed the snow as no longer necessary, and so symbolising how the confusion within Strange’s soul is dissipating as well.

Ditko’s got a great sense of visual symbolism in general, which he conveys with subtlety and economy. Panel 5 of page 4 shows us the sanctum from the outside, on an isolated mountain cliff, snowed in, with deep cloud behind it; Panel 5 of page 8, the exact same spot on the page, gives us a view of the sanctum under bright sun, the clouds gone, only a single black cloud right in front of the sun’s face. Where the page 4 panel gives us dialogue of Strange scoffing at magic, the dialogue on page 8 is the Ancient One explaining that he knows Mordo is evil but is keeping him close for his own purposes — the cloud in front of the sun, as it were. Note that the cut to the exterior shot here isn’t something directly relevant to the dialogue; it’s a simple visual way of showing how the Ancient One has dismissed the snow as no longer necessary, and so symbolising how the confusion within Strange’s soul is dissipating as well.

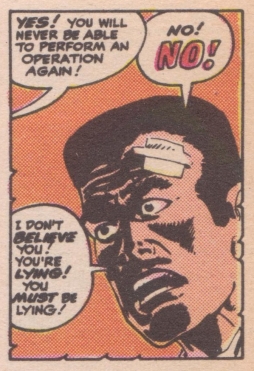

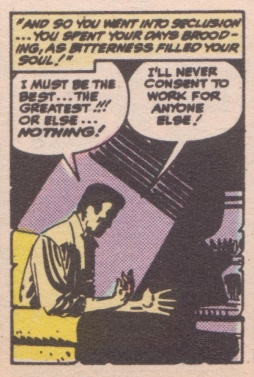

In general, I think Ditko plays extraordinarily well with light and shade in this story. He makes the Ancient One’s sanctum a subtly unsettling shadow-filled lair — but then it’s not as bleak as the film-noirish panel of Strange sitting in darkiness in flashback, the shadow of a blind on the wall behind him like a tenebrous guillotine, as he swears “I must be the best … the greatest!!! Or else … nothing!” It’s an ominous line, hinting at the man’s self-loathing, since we know he cannot ever be the best again — at least, at surgery. And even the image in that panel seems almost normal next to the brutalist, oddly distorted, and heavily shadowed face of an agonised Strange hearing that he will never be a surgeon again. Finally, consider the last panel on page seven, as Strange sees the threat Mordo poses; Ditko’s drawn a symbolic background of vertical lines, seeming to push down on Strange, even as the lines of the floorboards subtly draw the gaze to him, making him the absolute core of the composition — just as the panel is, in a way, the core of the story.

Conversely, when Strange asks the Ancient One to take him as a student, there’s a smoking brazier in the foreground, a seemingly unnecessary element that not only adds visual interest to the shot, but also insists on the presence of light. You could say Ditko’s making his light source clear, but his lighting all through the story’s been so expressionistic it hardly seems necessary. Again and again we see faces lit dramatically, not necessarily realistically — Strange in panel 3 of page 7, for example, but to an extent Mordo in panel 1 of page 6 as well, since whatever light is shining on him there seems gone in the next panel.

But clearly the story’s most dramatic lighting element, and indeed design element, and perhaps plot element, is magic. Ditko’s conception of how to depict magic on the comics page has probably never been equalled; it’s a heady mix of abstract mathematical shapes and organic inking, flat colours and thick outlines that mesh perfectly with the printing techniques of the medium. Look at the gag that forms around Strange’s mouth; in one panel it’s a menacing hand-like shape reaching for him, and in the next its upper part is still shapeless, ethereal, but the main body of it has real weight and definition, with metallic rivets giving it an extra sense of detail. The spell that attacks the Ancient One is a taste of the radical design sensibility Ditko would go on to bring to the book, an awareness of the comics page as a two-dimensional plane, mixed with a simplicity of shape and colour contrasting with the more detailed forms of characters and setting. Look at the lightning bolts that Mordo uses to bind Strange; the jagged diagonals bring energy to the composition, and you can almost feel them shocking the hapless doctor.

But clearly the story’s most dramatic lighting element, and indeed design element, and perhaps plot element, is magic. Ditko’s conception of how to depict magic on the comics page has probably never been equalled; it’s a heady mix of abstract mathematical shapes and organic inking, flat colours and thick outlines that mesh perfectly with the printing techniques of the medium. Look at the gag that forms around Strange’s mouth; in one panel it’s a menacing hand-like shape reaching for him, and in the next its upper part is still shapeless, ethereal, but the main body of it has real weight and definition, with metallic rivets giving it an extra sense of detail. The spell that attacks the Ancient One is a taste of the radical design sensibility Ditko would go on to bring to the book, an awareness of the comics page as a two-dimensional plane, mixed with a simplicity of shape and colour contrasting with the more detailed forms of characters and setting. Look at the lightning bolts that Mordo uses to bind Strange; the jagged diagonals bring energy to the composition, and you can almost feel them shocking the hapless doctor.

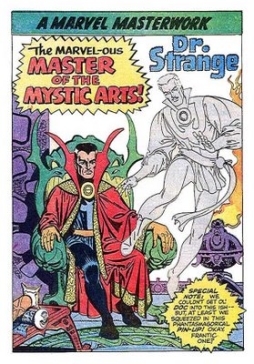

Before moving on from Ditko’s art, it’s worth talking about his character design as well. All three characters here had appeared before, but the way he draws them is highly distinctive; the heavyset Mordo contrasting with the lithe Stephen Strange, the Ancient One always seated and calm. In particular, Ditko draws Strange in this story in a range of ways, going through a number of emotions and stages of life. The smirking phsyician is different than the man breaking down after hearing about the consequences of his accident; the harrowed drifter is different than the near-Indiana-Jones-ish adventurer who makes his way around the world and up the side of a mountain to a mysterious wise man.

Ditko depicts emotion and tension with variety in facial features and body language, pulling us into Strange’s head. I think he draws Strange as surprised, tense, and emotionally off-centered in a way that he never does elsewhere. Strange can be under pressure in other stories, even worried or enraged, but it doesn’t show as easily on his face as it does here. This is a different man, a point I think Ditko underscores quite subtly. Not that he’s above the occasional little extra touch; it took me a while to notice that Strange seems so different in this story in part because the little fringes of white hair at the sides of his temple don’t appear until the end of the final panel — this is a younger man, but perhaps one who, however much he’s suffered up to this point, comes to see more disturbing things yet as he goes deeper into the world of magic.

But if Ditko’s visual conception of the characters is particularly strong, so too is their narrative. Strange, Mordo, and the Ancient One all have intensely-felt and clearly-defined wants. I don’t think that’s actually necessary to a story, but in a tight piece like this, it helps to keep things moving. It’s dramaticaly concise, too; the Mordo-Ancient One relationship appears simple and placid on the surface, but actually is a static balance of opposing forces, which Strange’s entry may disrupt. Strange’s choice, his decision to take up magic, is the fulcrum on which the entire story rests. And the story builds perfectly to that point, to the call-and-response of Strange’s internal monologue in the last panel of page 7 and the first panel of page 8. And the consequences follow naturally as well, an elegant unfolding of events, explaining all that has gone before and rounding off the tale with perfect fairy-tale logic.

But if Ditko’s visual conception of the characters is particularly strong, so too is their narrative. Strange, Mordo, and the Ancient One all have intensely-felt and clearly-defined wants. I don’t think that’s actually necessary to a story, but in a tight piece like this, it helps to keep things moving. It’s dramaticaly concise, too; the Mordo-Ancient One relationship appears simple and placid on the surface, but actually is a static balance of opposing forces, which Strange’s entry may disrupt. Strange’s choice, his decision to take up magic, is the fulcrum on which the entire story rests. And the story builds perfectly to that point, to the call-and-response of Strange’s internal monologue in the last panel of page 7 and the first panel of page 8. And the consequences follow naturally as well, an elegant unfolding of events, explaining all that has gone before and rounding off the tale with perfect fairy-tale logic.

The story’s cleverly structured in a number of ways; when we get Strange’s background in a flashback narrated by the Ancient One, who is probing his soul, we get insights into two characters at once. It’s a very concise approach, establishing both men as sympathetic while keeping Strange at centre-stage as the figure who must develop and go beyond himself to reach his full potential. Mordo isn’t developed as fully as these two, but has his moments — he smirks nicely when he tells the Ancient One to send Strange home, and Ditko’s art seems to tell you everything you could want to know about him in just that one panel. Intriguingly for a man who seems concerned with power, much of his magic seems to be based on supplicating greater forces, specifically an entity named Dormammu. This will play out across the stories to follow, as we meet the sinister (or dread) Dormammu, and see Mordo, eventually outclassed as a sorcerer by Strange, desperately make deals with the extradimensional tyrant for more power.

It’s interesting that magic in the story is a sinister force, for the most part — true black magic, or seeming so. We watch the Ancient One use magic against Strange, holding him helpless; then, after we come to respect the Ancient One, Mordo uses it against him before laying a curse upon Strange. Magic is only used for a clear good at the end of the story, after Strange agrees to become the Ancient One’s pupil, and the Ancient One dispels Mordo’s curse. It’s a subtle way, I think, to emphasise the, well, strangeness of the whole situation, the unsettling nature of magic. It’s not a benevolent technology; it’s something weird, that can come out of nowhere and strike you down. It’s scary, and Ditkio’s handling of it here helps to give Strange’s decision real weight. If his decision was simply to study some new and powerful science, it wouldn’t be a surprising call. But this is magic, with spiritual significance, with consequences for the soul. The structure of the story helps make that subliminally clear to the reader, and gives weight to Strange’s choice.

I think it’s telling that the Ancient One actually holds out hope of some kind of cure for Strange early on. He says he can’t help the selfish Strange, but adds: “If you will stay here … study with me … perhaps you will find within yourself the cure you seek!” But Strange’s response is: “I should have known! It was just a waste of time!” This, after the Ancient One has just held him helpless in mid-air and studied his soul through magic. Partly that can be attributed to Strange’s unease and disappointment, but partly I think it suggests that he’s deeply averse to the study the Ancient One suggests: “Naturally, man of the western world, you must not allow yourself to believe in magic!” says the Ancient One, gently ironic. “It would be … unseemly!” Of course, there’s also the implication that Strange is averse to self-examination — such as the Ancient One just put him through. But the whole course of the story leads up to a point where Strange has no choice but to look at himself, and to go beyond the worldview he used to have; a worldview that offers him no hope, whereas the magic that has buffeted him and threatened him gives him a glimmer of possibility. The chance once again to be the best.

I think it’s telling that the Ancient One actually holds out hope of some kind of cure for Strange early on. He says he can’t help the selfish Strange, but adds: “If you will stay here … study with me … perhaps you will find within yourself the cure you seek!” But Strange’s response is: “I should have known! It was just a waste of time!” This, after the Ancient One has just held him helpless in mid-air and studied his soul through magic. Partly that can be attributed to Strange’s unease and disappointment, but partly I think it suggests that he’s deeply averse to the study the Ancient One suggests: “Naturally, man of the western world, you must not allow yourself to believe in magic!” says the Ancient One, gently ironic. “It would be … unseemly!” Of course, there’s also the implication that Strange is averse to self-examination — such as the Ancient One just put him through. But the whole course of the story leads up to a point where Strange has no choice but to look at himself, and to go beyond the worldview he used to have; a worldview that offers him no hope, whereas the magic that has buffeted him and threatened him gives him a glimmer of possibility. The chance once again to be the best.

It’s an interesting point that the story takes little interest in super-powers for their own sake, or in the ways by which Strange learns the use of power. There’s no list of skills or abilities that he comes to know. Instead it’s all about the moment of decision. That is where Stephen Strange, master of the mystic arts and sorcerer supreme, comes into existence. Ditko’s other great Marvel character — lesser than Strange, but still great — gains spider-powers, and then learns through tragedy what it is to be a good man. Strange gains power by choosing to be good. That is how you negotiate the world, says Ditko (or perhaps ‘how you must face the world’ would be more accurate, given Ditko’s later Objectivist stance). Whether it is the world of magic or any other world, you make that choice, and everything else will follow.

Still, although those of us who read comics are now used to thinking of Strange as a powerhouse character, who deals with gods as equals and is on a first-name basis with cosmic entities, the hapless over-matched Strange of this story echoes throughout the rest of Ditko’s run. Under Ditko, Strange usually faces creatures more powerful than he is — sometimes vastly more powerful. Or he finds himself facing weaker opponents, but only when caught in some trap or other, his own abilities diminished. One unforgettable story has him defeat three rival wizards with his face covered in a mask and his hands bound so that he can’t cast spells; almost literally, he goes against three-to-one odds blindfolded and with his hands tied behind his back.

Grant, in the article I mentioned up above, makes that point that Strange’s greatest triumphs come through his functioning as trickster, out-planning or out-manipulating the bad guys. His enemies are blinded by arrogance or love of their own power, but Strange has a clearer sense of his limitations, because he’s not fighting for himself but for the world as a whole. I think this shows up here in his origin. Fundamentally, Ditko’s not concerned with power. He’s concerned with a man making the right choice. And because of that, he tells a powerful tale around the choice and its consequences.

Grant, in the article I mentioned up above, makes that point that Strange’s greatest triumphs come through his functioning as trickster, out-planning or out-manipulating the bad guys. His enemies are blinded by arrogance or love of their own power, but Strange has a clearer sense of his limitations, because he’s not fighting for himself but for the world as a whole. I think this shows up here in his origin. Fundamentally, Ditko’s not concerned with power. He’s concerned with a man making the right choice. And because of that, he tells a powerful tale around the choice and its consequences.

A former editor-in-chief of Marvel, who admitted having no feel for fantasy, said he felt Strange didn’t work as a character because the rules of his powers weren’t clear. I think that’s wrong, and I think Neil Gaiman and Grant Morrison got it right in their recent talk for Entertainment Weekly:

NG: The other thing I love that you hear all the time from movie executives is, “What are the rules of this world?” Nobody gives you rules for any world. You figure it out as you go along and weird s— happens.

GM: And obviously rules eventually arise, but it comes from the narrative. And it doesn’t have to be this world’s rules. Adults need to get a grasp of this. These things aren’t real and we can make anything happen. And that’s exactly what’s so wonderful about it.

We learn what we need to learn about Strange’s powers through the narration. But they don’t really matter, not in the specifics. We get a general sense of who is more powerful than who, and why; and then we see what Strange does — how he misdirects people, acting as a true magician, how he is crafty even when his power is not overwhelming. This is enough. This is the point. This is why people who say Strange must be depowered to be relateable are wrong; Ditko knew Strange must have great power to wrestle with gods, just not so much as to be easily able to overcome them. He knew not to lay down rules needlessly, for they will define your stories.

Ditko knew that a story can turn upon a man’s moral choice. And that such a choice can become the most important thing in the world. The fantasy of Strange’s world helps to make that point clear, just as any setting, any set of givens, in any story exist in order to make the thematic point clearer and more resonant. In writing about Strange’s most important early choice, in writing and drawing the story that would define him, Ditko crteated a perfect eight-page fable, cleverly told and powerful. The story he would go on to tell with Strange brought the character into many incredible places, some of which are still being exploited by Marvel decades on. But the many uses to which Ditko’s tales and characters have since been put should not be allowed to obscure his original vision, or his original work. It’s well worth visiting, and re-visiting.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

That was great, Matthew. I enjoyed the article immensely. This title was one of my favorites up through the mid-1970s. Well done!

[…] one of the most distinctive stylists in American comics. I’ve written before about his supreme accomplishment in fantasy, but Stalker’s an interesting work in its own right. Ditko creates a setting, a very specific […]