Art of the Genre: Leiber, Mignola, and Graphic Novels

At that time I also wasn’t much of a reader. Sure, I read almost every day, taking in as much fantasy as I could, but for the most part it was also commercially driven stuff that in the final call of ‘what matters in fantasy’ it would almost all be found woefully lacking.

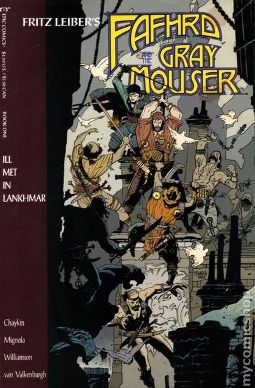

So it was with great interest that I discovered Epic Comics rendition of Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser on my comic shop’s shelves. It was noteworthy because it featured art by Mike Mignola, was adapted by Howard Chaykin, and had a kind of darkness to it that was antithesis to the flare of most superhero books coming out of the early stages of the comic boom.

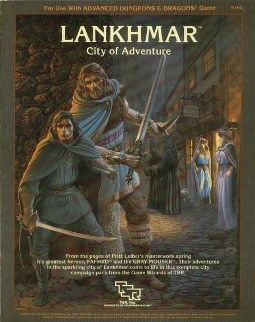

For me this series created a kind of enigma, that being that I loved fantasy but had only associated with Fritz Leiber in the TSR gaming supplement Lankhmar: City of Adventure. [Note: At the time I role-played in TSR’s Lankhmar, the song ‘One Night in Bangkok’ was on the radio and to this day I can’t say the world Lankhmar without setting it to a British vocal intonation accompanied by the words ‘City of Adventure’, just as Murry Head would began his song with ‘Bangkok, Oriental Setting’. BTW, it has to be the only Top 10 song in history that makes Chess seem downright cool.]

The cover for Book One, Ill Met in Lankhmar, is something straight out of a John Woo movie, even white doves flying around the battle. We are shown Fafhrd and Mouser in all their rooftop glory, and I have to say I almost pity the collection of warriors around them; especially the one holding Fafhard’s belt before the barbarian’s sword puts an end to his miserable existence.

Ill Met, of course, introduces us to the duo as a pair, both men having first taken their steps into adventure with the winning of their true loves in solo adventures, Mouser’s delicate noble flower Ivrian, and Fafhard’s powerful malcontent Vlana, having found home with these two prior to their journey to Lankhmar. This tale, however, ends that love affair in gruesome fashion, but it serves the purpose of setting our venerable sword and sorcery fellows on all the rest of their famed adventures together.

This mighty tale won Leiber both the Nebula and Huge for best Novella in 1970 and 1971 respectively, and it takes the full volume of Book One to deliver it. Still, this isn’t my favorite story in the Lankhmar pantheon, and I’d have to wait a few more volumes for that tale to come forth.

I always enjoyed the travelling duo, but when witnessed in Mignola’s depiction, I think it becomes even more alive. Mignola, you see, seems to believe in a concept of art that I adhere to, that being that characters need to change clothes. One thing that always annoyed me about comics or animation was that unlike role-playing or real life, characters became static representations that never ‘upgraded’ or changed what they wore from day to day. This is almost universally true of American 80s animation [ala G.I. Joe, MASK, Transformers], and in most cases is also the case in hero driven comic books [save for Iron Man who was always redesigning armor which probably was a primary contributing factor to him being my hands down favorite super hero.]

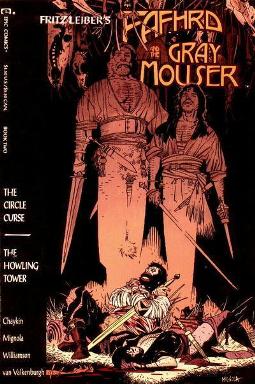

Anyway, Mignola does what I love here, as the duo tends to change and evolve as they progress, their outfits and equipment morphing with their travels. In The Circle Curse for example Fafhrd has 3 costume changes in 13 pages, which for a comic is extreme, and I applaud any artist willing to take the time and effort to pen such adjustments.

Mignola delivers his own brand of beauty in these pages, and as I’ve moved on with two decades of imagery, I can still see why I was taken with his female depictions even after the wonder of more socially acceptable artists have worn off.

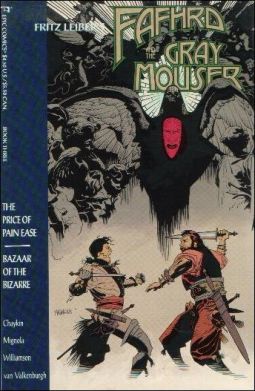

This volume places our heroes back in Lankhmar for a second stint in the fabled city. Two stories, The Price of Pain Ease, and Bazaar of the Bizarre, appear within. Both prove worthy of inclusion, and Chaykin’s adaptation and Mignola’s art make each story sing with page-turning pleasures.

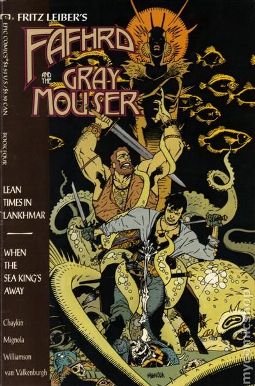

So we come to Book Four, and believe it or not, the editors decided to save my absolute two favorite Fafhrd and Mouser stories for the final volume. Lean Times in Lankhmar and When the Sea King’s Away are stellar, and although I think this cover is the weakest of the lot, the pages within do well to depict the weight of the tale.

Still, one can never fully realize the wonder of Lean Times in Lankhmar unless you read the tale in full, and Chaykin fails to capture what makes the story so dear to me in the first place, the absolute lambasting of organized religion. You see, Leiber worked for a time as a lay preacher, and his knowledge of religion and both its rise and fall are told in such eloquence in this tale that I keep it beside my bed to remind me just how reactionary faith can be.

Why do I love When the Sea King’s Away? Sex of course! Not to say that there is even a bit of sexual verse in this tale, but it’s all about the subtlety that flames my mind. Depending on your thinking [glass half full, or glass half empty] this story is either a torrid romp among aquatic demi-gods or a brush with intercourse that could have been. I’ve debated it many times with fellow authors, but I like to use this story as a barometer of my own work, as if to confirm that many times ‘less is more’.

Ok, I still got his point, that being that sex doesn’t have to drown you with adjectives to get it across that people are having it, and in When the Sea King’s Away, Leiber writes of sex in masterful fashion, so much so that you can’t actually prove it’s happened! Really, I dare you to find this short story and read the part within the Sea King’s cave and then come back and tell me you can definitively prove what has occurred…

Well there you have it, my personal take on Leiber, Mignola, and four wonderful graphic novels. Over the passing of the years I’ve come to both adore Mike Mignola and Fritz Leiber, and I want to remind everyone reading this that the Nameless Pulp Project is now a week old at The LA Gamer and I’m still hoping that people will come over and help build a brand with me because like the above, it’s what I’m trying to do, create great swords and sorcery pulp fiction with outstanding art, but I’m going to need some fantastic writers to do it!

[…] If you’ve been around a while, you probably have heard of Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Well, did you know that Mike Mignola (the guy behind Hellboy) created a comic version of Fafhrd for Epic Comics? Neither did I! Learn more at Black Gate in Scott Taylor’s article about Leiber, Mignola, and Graphic Novels… […]

[…] If you’ve been around a while, you probably have heard of Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Well, did you know that Mike Mignola (the guy behind Hellboy) created a comic version of Fafhrd for Epic Comics? Neither did I! Learn more at Black Gate in Scott Taylor’s article about Leiber, Mignola, and Graphic Novels… […]