Masterpiece: The Sword of Rhiannon by Leigh Brackett

I committed a major heresy, in public and on record, against the sword-and-sorcery community when I stated on the recording for a podcast that, in the realm of “sword-and-sorcery” fiction, I prefer Leigh Brackett over Robert E. Howard. Although at least one participant on the podcast seconded my opinion, I do understand why most sword-and-sorcery readers cannot go with me on this. Howard is, after all, the Enthroned God of the genre. And, strictly speaking, Brackett did not write fantasy or historicals. Her specialty was action-oriented science fiction with heavy fantasy influences, the sub-genre of science-fantasy known as “planetary romance.” (Sometimes called “sword-and-planet.” I hate that term.)

I committed a major heresy, in public and on record, against the sword-and-sorcery community when I stated on the recording for a podcast that, in the realm of “sword-and-sorcery” fiction, I prefer Leigh Brackett over Robert E. Howard. Although at least one participant on the podcast seconded my opinion, I do understand why most sword-and-sorcery readers cannot go with me on this. Howard is, after all, the Enthroned God of the genre. And, strictly speaking, Brackett did not write fantasy or historicals. Her specialty was action-oriented science fiction with heavy fantasy influences, the sub-genre of science-fantasy known as “planetary romance.” (Sometimes called “sword-and-planet.” I hate that term.)

I love Robert E. Howard’s work; it’s foundational for me. But, it’s “not that I love Howard less, but that I love Brackett more.” To that extent, I want to promote the sheer awesomeness that is Leigh Brackett whenever I can. And in her 1949 novel The Sword of Rhiannon (buy it here!) she reached what I believe is her apex: a planetary romance set across an ancient version of Mars, crammed with sword-swinging action, pirate-style swashbuckling, alien super-science, a hero as flinty as granite, an alluring and surprising femme fatale warrior, and an overarching theme of redemption, loss, and futility that ends up pushing what sounds like a standard adventure into a work of intricacy and overwhelming emotion.

Leigh Brackett (1915–1978), a long time resident of the same neighborhoods in Los Angeles where I grew up and still live, was a student of Howard’s work and an immense admirer. However, she didn’t copy him when she started her own career, but infused his passionate style with her own passions. Brackett shows the influence of other predecessors — Clark Asthon Smith, A. Merritt, C. L. Moore, Henry Kuttner, Otis Adelbert Kline, Edgar Rice Burroughs — but her mixture is blended so perfectly that all of it feels fresh and driven. I just finished another re-reading of The Sword of Rhiannon, and I am as thunderstruck as ever with how damn great Leigh Brackett was at what she did. Even more, I am awed at how modern her tale feels, even though the outer hull shows it as an old-fashioned pulp romance. Not that there’s anything wrong with the old pulp style; I still read Edgar Rice Burroughs avidly. But Brackett to this day stands in a class of her own.

Leigh Brackett emerged in the early ‘40s in the pages of Astounding Science Fiction. But she was never a hard and fast member of John W. Campbell’s bullpen at Astounding that formed the “Golden Age” of science fiction. She was more attuned to wild adventure, science fiction as a stage for hard-boiled characters and Western-style loners. She found her home in the more lurid magazines of the time, such as Planet Stories and Startling Stories, where she became the ruling figure, a Brobdingnagian among Lilliputians.

She vanished from the pulp magazine scene in the middle of the decade when she turned to screenwriting with the adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep for director Howard Hawks. (She co-wrote the script with somebody named Faulkner. Never heard of him.) However, her time with movies and TV was an on-again off-again affair, and her expectations of continual success in the 1940s from Hollywood scripts fell short. “Since 1957 I’ve worked quite a lot in films and television,” she wrote a few years before her death, “but I’ve never forgotten that early lesson: don’t count on it. The bad thing about film or TV work is that you have to wait for someone to ask you to do it, whereas you can sit down and write a novel when and as you wish, and if you have a reasonable degree of competence you can be fairly sure of selling it somewhere … Besides, I like writing science fiction.”

And so, in the late 1940s, Leigh Brackett returned to magazine science fiction in a major way, writing novella and novel-length stories for her most dependable markets and turning out the best work she had done so far. It was during this period that she created her most famous fictional hero, Eric John Stark.

And so, in the late 1940s, Leigh Brackett returned to magazine science fiction in a major way, writing novella and novel-length stories for her most dependable markets and turning out the best work she had done so far. It was during this period that she created her most famous fictional hero, Eric John Stark.

The Sword of Rhiannon was one of her big successes of this period. It first appeared under the title The Sea Kings of Mars in the June 1949 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories, Standard Magazines’ successor to Hugo Gernsbeck’s 1930s pulp Wonder Stories. (Standard slapped the word “Thrilling” on every magazine they purchased.) Ace Books published the novel in paperback under its new author-approved title in 1953. Brackett later explained that the name change was to scuttle “Mars” from the header, since advances in scientific knowledge of the Red Planet made publishers fear that readers would be leery of an action-swashbuckler set there. (Bizarrely, Disney just made a similar decision and sliced “…of Mars” off the title of their upcoming John Carter of Mars. Stoooooopid! Bad mouse!)

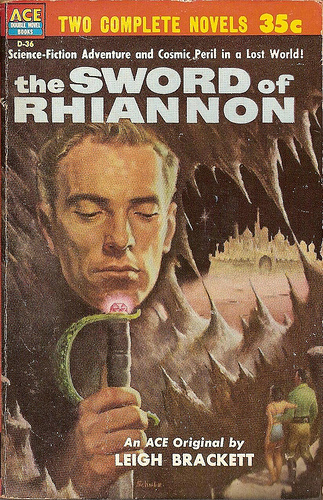

Ace wanted to sell The Sword of Rhiannon to readers of sword-and-sorcery, so they paired it as an Ace Double with The Hour of the Dragon, the only Conan novel that Robert E. Howard wrote. (It’s Ace Double D-36 if you are interested in minutiae. Apparently, I am.) This volume must be considered the greatest “twofer” in the history of fantastic fiction. Imagine the reaction of the unsuspecting thirteen-year-old kid who plucked that off the paperback spinner at Thompson’s Drug Emporium one sleepy summer afternoon in 1955, paying a whole 35¢ — a quarter and dime! — for the pleasure of having his or her life changed. It must have been like hearing Elvis for the first time.

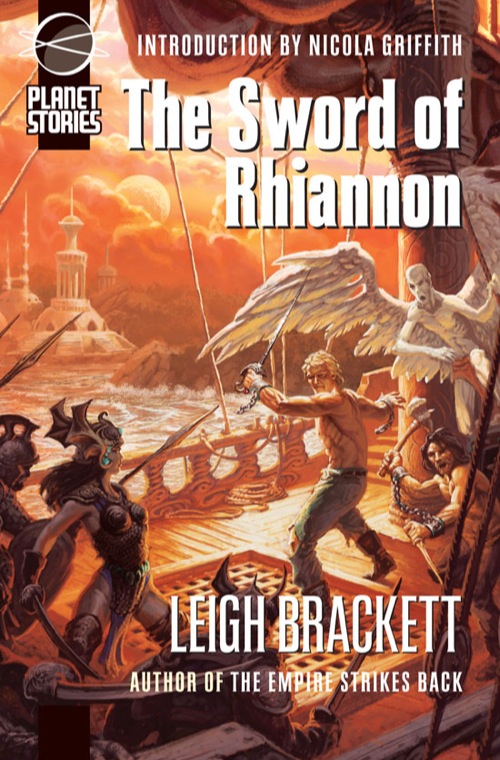

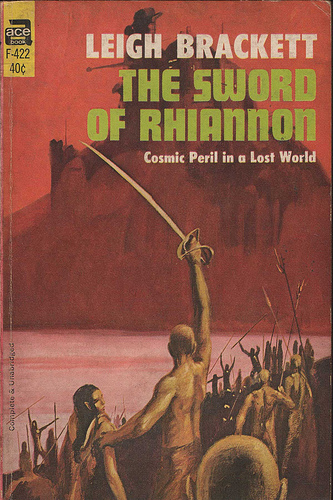

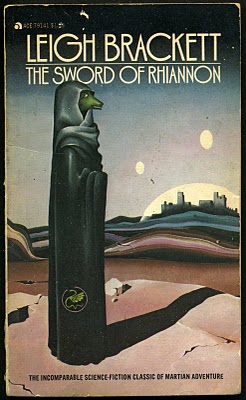

Two years later, The Sword of Rhiannon had its hardcover debut in the UK from publisher T. V. Boardman. Ace’s first solo-paperback printing was in 1967, with cover art by John Schoenherr. The first edition I ever owned was Ace’s 1975 paperback printing, with a more abstract piece of art on the cover fitting the decade. I still own that copy, but now I read from the recent edition from Paizo Publishing, part of its superb Planet Stories line. Ironic that this is one of Leigh Brackett’s few science-fantasy adventures that didn’t appear in the original pulp Planet Stories.

The Sword of Rhiannon takes place on the Mars that Brackett had established through her earlier stories: a dusky, dying world of canals and crumbling cities. The protagonist, Matthew Carse, is an ideal Brackett hero. Within this one character, a reader can see how much George Lucas borrowed from reading Leigh Brackett. (Lucas hired Brackett to write the first draft of The Empire Strikes Back, but she died soon after completing it and almost nothing of her work appears in the final version.) Carse is a powerful, imposing man who matches his physical prowess with shady morality. He was once an archaeologist, but on this twilight Mars he is now a thief and a looter acquainted with the back-alleys of the city of Jekkara. The only law he obeys is force.

The novel opens on a scene that could have come from a Conan tale. Carse, leaving one of Jekkara’s sense-drowning drug dens, notices someone stalking him in the alleys. Carse gets the drop on his follower, and finds another thief, a Martian named Penkwar.

Penkwar wants Carse to help him sell a valuable item that he uncovered from a tomb. It’s no ordinary relic, but the famed Sword of Rhiannon. In Martian mythology, Rhiannon was rebel amongst the “god-hero” race the Quiru. In the forgotten days of Mars, when it was green and wide oceans covered it, the super-science of the Quiru sealed Rhiannon in a tomb because he dared to give the science of the Quiru to the Dhuvians, a race of serpent-people. Rhiannon has come down in legend as “The Cursed One.”

Penkwar wants Carse to help him sell a valuable item that he uncovered from a tomb. It’s no ordinary relic, but the famed Sword of Rhiannon. In Martian mythology, Rhiannon was rebel amongst the “god-hero” race the Quiru. In the forgotten days of Mars, when it was green and wide oceans covered it, the super-science of the Quiru sealed Rhiannon in a tomb because he dared to give the science of the Quiru to the Dhuvians, a race of serpent-people. Rhiannon has come down in legend as “The Cursed One.”

A note regarding the name Rhiannon: The name is a common female Welsh one. It belongs to a character in Welsh mythology who appears in the Mabinogi and some Arthurian legends. The novel’s Rhiannon, a male of a super-intelligent race, has no apparent connection to the mythological Rhiannon. Perhaps Brackett simply liked the name. There is an Arthurian echo in another character name in the novel, Ywain, one of the Knights of the Round Table. The Ywain of The Sword of Rhiannon is a woman, however, which makes me wonder if Brackett intended a gender-swap between the names Rhiannon and Ywain. Brackett had already used Rhiannon in an earlier story about Mars, “The Sorcerer of Rhiannon” (1942), but in that story it is the name of an island group. Brackett’s Martian history isn’t uniform, so there’s no reason to imagine a direct connection between those islands and the Rhiannon of this novel.

Carse has ambitions beyond possessing the Sword of Rhiannon: he wants to go to the tomb and loot it, mixing in equal parts his desires as a thief and an archaeologist. But once inside the legendary tomb, Carse’s amazement at a great black sphere gives the jaded Penkwar time to shove the Earthman into the sphere…

. . . which hurtles Carse back millions of years to the lush time of Mars, where the empty basins roll with water. It is a place that he knows of from myth as “a world of only rudimentary science, a world of sword-fighting sea-warriors whose galleys and kingdoms had clashed on long-lost oceans.” And so, Brackett lays down the science-fantasy adventure ahead, where technology is magic, and the law of the sword and the muscles behind it rule pirate-filled oceans.

Carse hasn’t arrived alone, however. He feels aware of another presence in his head, one that came to him as his tumbled through the black sphere.

As Carse encounters the dangers of this younger Mars, he and the readers learn about the power struggle on the planet. The Empire of Sark rules most of the lands around the sea, with only the Sea Kings of the West holding out against them. The legend of Rhiannon is as strong in this past as it was in Carse’s time. The Quiru abandoned Mars after Rhiannon gave their wisdom to the Dhuvians, but before leaving they locked the traitor’s body with all the artifacts of power he stole. Both the Empire of Sark and the Sea Kings wish to obtain that power — and Carse is the only person who knows the tomb’s location.

The Dhuvians are not the only “Halflings” on this planet, mixtures of men and animals. There are also aquatic Swimmers and the winged Sky-Lords. Carse encounters both when Lady Ywain, daughter of one of the kings of Sark, takes him as a galley slave on her ship.

The sequences on the galley are reminiscent of many Roman-themed historicals, such as Talbot Mundy’s Tros of Samothrace, as well as A. Merritt’s fantasy The Ship of Ishtar. Brackett’s blending of the high adventure with atavistic prose makes for hallucinatory reading:

It was fear, the ancient evil thing that crept among the grasses in the beginning, apart from life but watching it with eyes of cold wisdom, laughing its silent laughter, giving nothing but the bitter death.

It was the Serpent.

The primal ape in Carse wanted to run, to hide away. Every cell of his flesh recoiled, every instinct warned him.

But he did not run and there was an anger in him that grew until it blotted out fear, blotted out Ywain and the others, everything but the wish to destroy utterly the creature crouching beyond the light.

His own anger — or something greater? Something born of a shame and an agony that he could never know?

A voice spoke to him out of the darkness, soft and sibilant.

“You have willed it. Let it be so.”

Ywain enters the story as a simple villain: a beautiful but black-hearted warrior woman. However, throughout the novel Brackett plays against character expectations, maneuvering characters with subtle interactions. The interplay between Carse and Ywain is different from what readers might expect from the male-oriented dominance of the pulps, although it begins that way:

There was no love, no tenderness in that kiss. It was a gesture of male contempt, brutal and full of hate. Yet for one strange moment then her sharp teeth had met in his lower lip and his mouth was full of blood and she was laughing.

“You barbarian swine,” she whispered. “Now my brand is on you.”

Carse is filled with the masculine desire to dominate, and especially the arousal that comes from facing a resistant and powerful female, but it turns around here as the woman has the victory of virility on him.

Carse is filled with the masculine desire to dominate, and especially the arousal that comes from facing a resistant and powerful female, but it turns around here as the woman has the victory of virility on him.

Another possible romantic interest for Carse emerges in the beauty of red-haired Emer, sister of one of the Sea Kings, Rold. In a novel from the 1920s or ‘30s, she would be the blushing beauty destined for the hero’s embrace, and the stepping stone to royalty. Brackett has something much different awaiting Carse and Mars. This is not a world where the alpha-male, even a victorious one, can walk away with all the spoils.

Another surprising character is Boghaz, a Valkisian merchant who meets Carse in Jekkara and offers to guide him. Boghaz initially looks like a generic “shady but cowardly criminal” archetype, a fat, lazy schemer who will sell the hero at the first opportunity, and be the first to fall on his belly and whimper when the tables turn. And, for the most part, Boghaz does exactly this in The Sword of Rhiannon — and yet he still ends up one of the most loyal and heroic figures in the story. Carse and Ywain undergo the greatest change as the two protagonists, but Boghaz’s journey as a character is only a notch under theirs, and Brackett handles him with such subtlety that he emerges as an extremely moving character. His farewell to Carse is one of the highlights of the conclusion.

Carse himself is sometimes a repellant figure. Rapacious, manipulative, grossly self-interested — and the writing lets readers view him that way without apology. Unlike a Mike Hammer figure, where the author wants readers to like the tough aspects of the character, Brackett has made Carse someone to dislike and yet find fascinating because of his imperfections. He also has a literal internal conflict with the mind of Rhiannon using him as a vessel.

By the last third, the novel reaches the point of an epic filled with Shakespearean passion. The theme changes from that of an adventurer trying to survive to a tale about the expiation of the sins of the past of an entire planet. Carse, a man of doubtful heroism, is possessed by the mind of a traitor from eons past who wishes to reclaim his name and expunge his crimes. The Rhiannon–Carse combination, with the two fighting over who should have control, is a perfect way to chart the course of both figures toward the…

Oh, wow, the climax. Brackett unleashes poetic fury and Old Testament madness. She even has one character intone, “It is done” as the super-science fury at last subsides. Because that’s the only summation that could possibly mesh with the majesty of what has gone before.

However, in the last two chapters following the climactic scenes, The Sword of Rhiannon finds that the only way to top a masterful action finale is with heavy strokes of dark paint. Brackett’s prose reaches symphonic levels of a requiem as the tale winds down.

In these last chapters, The Sword of Rhiannon achieves a level of sublime power that feels like a miracle. I love Edgar Rice Burroughs, I adore A. Merritt. But their similar-plotted adventures do not have the resonance that Brackett achieves here. She creates the same exciting adventure, crafts similar greater-than-life characters, but layers over it an emotional sheen in which readers can see their reflections. And Brackett does this without “naturalism.” She never has her characters break away from the mythic canvas. Matthew Carse doesn’t change into the greater man he is at the end because Brackett threw moralizing moments of realization at him. He changes because all the world of the story changes; no one can go through the upheaval of this Mars and not emerge different. Brackett trusts the mythic power of the story to shape her characters, and trusts her own writing skill to achieve it without distractingly showing her hand. It is amazing craftsmanship done with the illusion of effortlessness. Like Rhiannon secretly getting into Carse’s mind and emerging slowly through his thoughts until he bursts forth into action, so does The Sword of Rhiannon begins quietly on the page and lets its characters and intriguing story burrow into the reader, finally emerging when called for into one of the supernovas of science fiction.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

I’d love to give some of her work a go, but can’t get it as an ebook. I’ll keep an eye out, however.

If you have Kindle, some of her work is available here. But I’ll have to stump for Paizo Publications and recommend purchasing their softcover of The Sword of Rhiannon. They do great jobs with the pulp they publish.

There are also some Brackett stories available as eBooks from Baen. (including “Sea-Kings of Mars”)

http://www.webscription.net/s-139-leigh-brackett.aspx

Great write-up, Ryan.

One of my favorite stories by one of my very favorite writers.

One of the interesting things about Brackett is that she wrote futuristic stories that were basically lamenting the past, with hard-boiled characters that go to other planets so they can wander around crumbling cities and decayed landscapes, feeling the immense history of it all (or in the case of this book, getting to actually experience it), which then maybe causes the reader to muse about the wonders we’ve missed from our own history.

Let me 1. encourage you in your heresy (I think Brackett and C.L. Moore are both right up there with Howard, at least) and 2. second the stump for Paizo. They’ve got beautiful reprints of Moore and Brackett that aren’t overpriced, accompanied by insightful introductory essays. I was actually a little disappointed in The Sword of Rhiannon the first time I read it for some reason (I read it right after the Skaith trilogy), but enjoyed it more a couple of years later when I reread it.

Thanks for the links, guys 🙂

Harvey –

Brackett is great. A sadly overlooked weird-fictional-saint.

I’m glad there are others in the cult of Planetary Romance ( I conceded to your favoured term ) and at it’s best, besting even ( some ) Swords + Sorcery.

Your Heresy is more than tolerated by myself, as I am The Patron Saint of Heretics. All Heretics, even the Heretics of Heresy.

[…] find echoes throughout science fiction and fantasy that came after. Leigh Brackett’s classic The Sword of Rhiannon, also a tale of Mars, takes Burroughs’s concept of the mythic past of the planet and makes it the […]

[…] anything in the previous book, and seems to predict the Mars of Leigh Brackett’s masterpiece The Sword Rhiannon: Here and there a roof of a building had fallen in, but for the most part they remained intact, […]

[…] the Leigh Brackett and ERB style of muscular planetary romance. (Try to imagine Hulk as the star of The Sword of Rhiannon!) And the whole enormous thing is available digitally from […]

[…] Brackett: American Writer, by Howard Andrew Jones Masterpiece: The Sword of Rhiannon by Leigh Brackett by Ryan Harvey Swordsmen in the Sky by Charles Saunders A Bout of Aboutness: Urban Fantasy and […]

[…] J.R.R. Tolkien, and Appendix N, Ryan Harvey’s review of another Planet Stories volume, Masterpiece: The Sword of Rhiannon by Leigh Brackett, and Howard Andrew Jones’ retrospective, Leigh Brackett: American […]

[…] Black Gate — “I love Robert E. Howard’s work; it’s foundational for me. But, it’s ‘not that I love Howard less, but that I love Brackett more.’ To that extent, I want to promote the sheer awesomeness that is Leigh Brackett whenever I can. And in her 1949 novel The Sword of Rhiannon she reached what I believe is her apex: a planetary romance set across an ancient version of Mars, crammed with sword-swinging action, pirate-style swashbuckling, alien super-science, a hero as flinty as granite, an alluring and surprising femme fatale warrior, and an overarching theme of redemption, loss, and futility that ends up pushing what sounds like a standard adventure into a work of intricacy and overwhelming emotion.” […]