The Dream-World of Lud-in-the-Mist

Hope Mirrlees’ stunning 1926 novel Lud-in-the-Mist begins with the following epigraph:

Hope Mirrlees’ stunning 1926 novel Lud-in-the-Mist begins with the following epigraph:

The Sirens stand, as it would seem, to the ancient and the modern, for the impulses in life as yet immoralised, imperious longings, ecstasies, whether of love or art, or philosophy, magical voices calling to a man from his “Land of Heart’s Desire,” and to which if he hearken it may be that he will return no more — voices, too, which, whether a man sail by or stay to hearken, still sing on.

It’s a quote from the classical scholar Jane Harrison, who was Mirrlees’ close companion at the time Mirrlees was working on Lud-in-the-Mist. It’s a perfectly chosen introduction to the book. It sets out the themes, and to an extent the method, which Mirrlees used: the conflict between instinctive desires and the conscious will, that tries to repress those desires and establish a social harmony — all symbolically realised through the imagery of myth and fantasy.

The sirens sang to Odysseus, who had himself lashed to his mast to hear their song while his crew went about their duties with their ears stopped up with wax. Apollonius of Rhodes says that they also sang to the Argonauts, but that their song was overcome by Orpheus, and the sirens threw themselves into the sea and became rocks. And I will note here, for reasons that should become clear later, that Apollonius also says that only a little later the Argonauts came to the garden of the Hesperides, in the far west, where the golden apples of Gaea had been kept, a marriage gift for Hera, until Hercules had took them as part of his labours.

These legends seem to have little to do with Mirrlees’ book. At least on the surface. The novel introduces us to Lud-in-the-Mist, a town of merchants and bankers, culturally similar to, say, a small eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century English or Dutch city. It’s the capital of the small country of Dorimare, which is bounded on the north and east by mountains, on the south by the ocean, and on the west by Fairyland. But the Dorimarites do their level best to ignore their western boundary. Like Odysseus’ crew, they have stopped up their ears.

These legends seem to have little to do with Mirrlees’ book. At least on the surface. The novel introduces us to Lud-in-the-Mist, a town of merchants and bankers, culturally similar to, say, a small eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century English or Dutch city. It’s the capital of the small country of Dorimare, which is bounded on the north and east by mountains, on the south by the ocean, and on the west by Fairyland. But the Dorimarites do their level best to ignore their western boundary. Like Odysseus’ crew, they have stopped up their ears.

It wasn’t always so. Dorimare used to be a duchy, with a hierarchy of priests of a seemingly-pagan religion. But some two hundred years before the story opens, there was a bourgeois revolution against the aristocracy, and against the priests. Duke Aubry was deposed. The burghers who took over Dorimare decided that the decadence of their former rulers had been caused by their indulgence in fairy fruit, which was now banned. Indeed all products of fairyland were banned, and even to speak of the fairies became a crime against good taste. Still, a scandalous book published — and banned — several years before the novel begins pointed out that Dorimarites had intermarried with fairies in the past, that the flora and fauna were still on occasion elf-touched, and that even the names of the Dorimarites hinted at fairy origins. So did their curses: “By the Golden Apples of the West,” one of them might exclaim, echoing what we eventually find to be “the most potent charm in fairy;” so returning us to myth, to the Hesperides, and to the sirens.

Fairyland, in Lud-in-the-Mist, is the abode of old aristocracy, like Aubry, and of religion and mystery. But it is the abode of many other things as well. Fairy fruit “had, indeed, always been connected with poetry and visions, which, springing as they do from an ever-present sense of mortality, might easily appear morbid to the sturdy common-sense of a burgher-class in the making.” The reference to mortality is intriguing. Mirrlees frequently associates fairyland with death, lending a dark texture to a book that otherwise seems sprightly. If one can easily read Mirrlee’s fairy fruit as being, like the fruits of Christina Rossetti’s “Goblin Market,” concerned with sexuality and the erotic, then it’s also easy to read it as connected with the passage of time, with death, and with the thanatic. Fairyland is the Freudian unconscious, the place of those primal urges from which dreams and deep desires come; and Mirrlees’ book becomes increasingly dreamlike as it progresses.

It’s probably no surprise at this point to say that the book covers the subversion of placid Dorimare by the incursion of fairy fruits, an extended parable of the conscious mind being undermined by the unconscious. Mirrlees takes the somewhat risky but entirely successful step of telling this story essentially from the perspective of the conscious mind, as opposed to the more immediately vital and dramatically attractive unconscious. One of the reasons she succeeds in this is by the strength of her dramatisation of the human society at Dorimare’s heart. Lud-in-the-Mist feels like a real community; its people are frequently petty and small-minded, but the characters love it and so we accept those flaws — just as we overlook the pettiness and small-mindedness of any community we love. Conversely, Mirrlees delicately underlines the cruelty of fairyland. Duke Aubrey is a rapist who hounded a jester to suicide for his own amusement. The immoralised impulses are not particularly pleasant.

It’s probably no surprise at this point to say that the book covers the subversion of placid Dorimare by the incursion of fairy fruits, an extended parable of the conscious mind being undermined by the unconscious. Mirrlees takes the somewhat risky but entirely successful step of telling this story essentially from the perspective of the conscious mind, as opposed to the more immediately vital and dramatically attractive unconscious. One of the reasons she succeeds in this is by the strength of her dramatisation of the human society at Dorimare’s heart. Lud-in-the-Mist feels like a real community; its people are frequently petty and small-minded, but the characters love it and so we accept those flaws — just as we overlook the pettiness and small-mindedness of any community we love. Conversely, Mirrlees delicately underlines the cruelty of fairyland. Duke Aubrey is a rapist who hounded a jester to suicide for his own amusement. The immoralised impulses are not particularly pleasant.

At the same time, the book is more sophisticated than this description makes it seem. It’s very clear that the rational world of the Dorimarites is itself a delusion. The rule of law they’ve established following the deposition of Aubrey is based on falsity; it refuses to mention Fairyland, and refers to ‘fairy fruit’ only as illegal textiles. “In the eye of the law,” we’re told, “neither Fairyland nor fairy things existed. But then, as Master Josiah had pointed out, the law plays fast and loose with reality — and no one really believes it.” This is no minor point. Much of the plot of the book comes to revolve around a murder case and its resolution, which is based very little on law or legal maneuvering.

So the paradox of the book is that the true fantasists are not the residents of Fairyland, but of Dorimare, who have built their fantasy on the repression of the fantastic. This is more than a conflict of fantasies. The story is, in essence, about denial. It’s about a people who deny their own mortality, who deny art and magic — it’s significant that Lud-in-the-Mist’s graveyard is called ‘the fields of Grammary,’ from ‘gramarye,’ magic, itself deriving from ‘gramarie,’ learning. It`s also significant that the family crypt of the Chanticleers, the leading family of the town, used to be a “pleasure-house” of Duke Aubrey’s; sex and death are wrapped up together.

The main character of the book, Nathaniel Chanticleer, mayor of Lud-in-the-Mist, was frightened as a young man by hearing a Note of pure music, and fears hearing it again as if it will mean the end of everything for him; he represses his romanticism, to the point where “he was apt to regard innocent things as taboo.” This recalls the arguments in Freud’s Totem and Taboo (published just 13 years before Lud); we can see Chanticleer and his society as neurotic, displacing their repressed fears and desires. Freud writes about society projecting its discontents onto its rulers in the form of rituals and taboos, and so Chanticleer, descendant of a family that itself deposed an aristocratic father-ruler in years past, reaches a low point in the book when he’s surreally declared by his subjects to be legally dead (significantly, a legal fiction).

The main character of the book, Nathaniel Chanticleer, mayor of Lud-in-the-Mist, was frightened as a young man by hearing a Note of pure music, and fears hearing it again as if it will mean the end of everything for him; he represses his romanticism, to the point where “he was apt to regard innocent things as taboo.” This recalls the arguments in Freud’s Totem and Taboo (published just 13 years before Lud); we can see Chanticleer and his society as neurotic, displacing their repressed fears and desires. Freud writes about society projecting its discontents onto its rulers in the form of rituals and taboos, and so Chanticleer, descendant of a family that itself deposed an aristocratic father-ruler in years past, reaches a low point in the book when he’s surreally declared by his subjects to be legally dead (significantly, a legal fiction).

But if the book seems to use Freudian ideas, it also seems to be a critique of Freud. Freud says “the asocial nature of the neurosis springs from its original tendency to flee from a dissatisfying reality to a more pleasurable world of phantasy. This real world which neurotics shun is dominated by the society of human beings and by the institutions created by them; the estrangement from reality is at the same time a withdrawal from human companionship.” Mirrlees suggests the opposite. The world of Dorimare and the law, the social world of human beings, is a function of repression and neurosis (Freud himself would argue something similar in his 1929 book Civilisation and its Discontents). Human beings collectively are estranged from reality. ‘Phantasy’ is a way of returning us to what is real; to express what cannot be said in any other way.

Which isn’t to say that the book’s structure or prose is unsophisticated. Quite the opposite; it is impressively dense with meaning. Symbols recur, images gain resonance with multiple use, and Mirrlees builds a sophisticated array of references which come to link up one to another. Consider the allusions to time, for example. At one point fairy fruit is hidden inside a grandfather clock. At another, Nathaniel’s old nurse tells him in part of a remarkable speech about time that “one learns that he is as quiet and peaceful as an old ox dragging the plough. And to watch Time teaches one to sing.” The nurse then sings for Nathaniel, who hears again the Note he fears: “But, strange to say, this time it held no menace. It was as quiet as trees and pictures and the past, as soothing as the drip of water, as peaceful as the lowing of cows returning to the byre at sunset.” So the imagery binds the Note to time; but also “There’s no clock like the sun and no calendar like the stars,” says the nurse. The sun and stars are part of the great charm of fairyland: “By the sun, moon, and stars, and the Golden Apples of the West!” And the stars, as the Milky Way, are associated with fairyland; which itself is linked with Nathaniel’s vision, in the later part of the book, of a broad white road. Everything ties in to everything else.

Which isn’t to say that the book’s structure or prose is unsophisticated. Quite the opposite; it is impressively dense with meaning. Symbols recur, images gain resonance with multiple use, and Mirrlees builds a sophisticated array of references which come to link up one to another. Consider the allusions to time, for example. At one point fairy fruit is hidden inside a grandfather clock. At another, Nathaniel’s old nurse tells him in part of a remarkable speech about time that “one learns that he is as quiet and peaceful as an old ox dragging the plough. And to watch Time teaches one to sing.” The nurse then sings for Nathaniel, who hears again the Note he fears: “But, strange to say, this time it held no menace. It was as quiet as trees and pictures and the past, as soothing as the drip of water, as peaceful as the lowing of cows returning to the byre at sunset.” So the imagery binds the Note to time; but also “There’s no clock like the sun and no calendar like the stars,” says the nurse. The sun and stars are part of the great charm of fairyland: “By the sun, moon, and stars, and the Golden Apples of the West!” And the stars, as the Milky Way, are associated with fairyland; which itself is linked with Nathaniel’s vision, in the later part of the book, of a broad white road. Everything ties in to everything else.

You can see it in the names of the characters. Chanticleer is the traditional name of the rooster, who greets the dawn and singals that it’s time to be awake. So of course Nathaniel’s enemy is the dreamy Endymion Leer, whose name harkens back to the nighttime dreamer in love with the moon. This connects to the fact that Fairyland, which among other things is the home of the dead, is to the west of Dorimare, the direction of night; and of the Hesperides, the daughters of the evening star.

Conversely, it’s one of the odd ironies of the book that there’s little actual mist described in the town of Lud-in-the-Mist. The nonexistent mist is simply symbolic. It’s an image of the confusion of the people, lost in delusions that they do not realise.

But although the confusions born of repression are a major part of the book’s themes, so too is ritual and initiation. Which may not bring happiness or wisdom, but which seem to be vital for uniting conscious and unconscious. We come to understand, by hints, that the old religion had a whole series of rites which survive in those strange names and oaths of the Dorimarites. And in the occasional old monument, one of which becomes a key symbol of union between the active world of humans and fairyland, with “the serenity and stability of trees.”

But although the confusions born of repression are a major part of the book’s themes, so too is ritual and initiation. Which may not bring happiness or wisdom, but which seem to be vital for uniting conscious and unconscious. We come to understand, by hints, that the old religion had a whole series of rites which survive in those strange names and oaths of the Dorimarites. And in the occasional old monument, one of which becomes a key symbol of union between the active world of humans and fairyland, with “the serenity and stability of trees.”

By the end, Nathaniels’ view on his Note has changed, opposites have been united, and a new awareness of Fairyland has in fact helped the Dorimarites in their trading with the outer world, with at least one new industry created. The point being that the integration of conscious and unconscious leads to new strength. And yet the book turns on itself at the very end, insisting on the falsity of all epitaphs, claiming that “the Written Word is a Fairy … speaking lying words to us in a feigned voice.” Perhaps it’s an insistence on the ultimate untameability of Fairyland, of the refusal of the elemental truths of the subconscious to be penned up in language.

There’s a quote on Wikipedia from Jane Harrison which runs as follows:

Every dogma religion has hitherto produced is probably false, but for all that the religious or mystical spirit may be the only way of apprehending some things, and these of enormous importance. It may also be that the contents of this mystical apprehension cannot be put into language without being falsified and misstated, that they have rather to be felt and lived than uttered and intellectually analyzed; yet they are somehow true and necessary to life.

It’s tempting to see that as in part a gloss on Lud-in-the-Mist’s distrust of the written word. It’s also tempting to see that as a hint both for Mirrlees’ adoption of fantasy after two realist novels, and perhaps also her relative silence thereafter (though she did continue to write poetry).

It’s tempting to see that as in part a gloss on Lud-in-the-Mist’s distrust of the written word. It’s also tempting to see that as a hint both for Mirrlees’ adoption of fantasy after two realist novels, and perhaps also her relative silence thereafter (though she did continue to write poetry).

At any rate, Lud-in-the-Mist is a great and deeply odd book. The characters aren’t fully-rounded, but they are flat in just the right way, in just the right satirical key. The story illustrates perfectly the distinction between reductive allegory, where every image has only one interpretation, and rich symbolism — where, as here, every reference has multiple meanings. It captures the feel of dreams like few other books, getting just right the strange balance of mundanity, incoherence, and significance that dreams have. And, crucially, the book is built out of well-turned sentence after well-turned sentence, a powerful work of language.

The book is in print for $8.50, and can be purchased here. (There are also used copies available.)

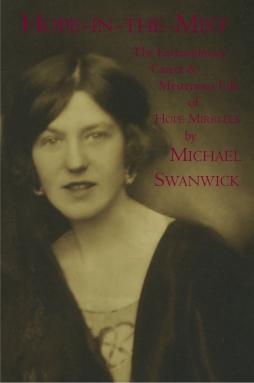

Or you can read about Hope Mirrlees here. Michael Swanwick’s written a study of Mirrlees that appears to be out of print; but he’s got some thoughts about her online here and here.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Thank you for writing this, Matthew! Great essay, as usual! I’ve never read anything by this author.

What a gorgeous novel Lud-in-the-Mist is. Hard to use with students who are not native speakers of English, as it turns out, precisely because of all that rich symbolism and sophisticated prose style.

It’s funny the way the book falls in and out of the genre’s collective consciousness. I first became aware of it when Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell came out, and Jo Walton described that novel as what the fantasy genre might look like if its lineage had passed primarily through Hope Mirrlees and Mervyn Peake, rather than Tolkien. Susanna Clarke blew my mind, so I had to rush out and read Mirrlees. Thank goodness for Neil Gaiman, who basically ushered it back into print by writing a foreword to it for a small press to use.

Only 200 copies of Michael Swanwick’s study were published, and I was lucky enough to snatch one of them up in the brief time they were available. Since Jane Ellen Harrison’s work on initiation rituals in the ancient world figured prominently in my dissertation on a Modernist poet who was obsessed with initiation and ritual, reading Swanwick’s book was sort of like reading Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, in that I already knew a lot about what was going on around her story, but next to nothing about Mirrlees herself.

Swanwick sums up her literary legacy by saying that she wrote two great masterpieces–this novel, and a long poem that was a Modernist tour de force and influenced T.S. Eliot and his circle–but that very few readers would ever connect both works. I need to track down that poem, because I’m in that narrow sliver of Venn diagram.

Sarah: You can find the poem online. You can find a .pdf here —

http://hopemirrlees.com/2009/paris-a-poem/

— and a .pdf is in fact needed, since being very modernist it plays about with layout and page design. It’s certainly an interesting piece; personally, I haven’t figured out how to connect the poem with the novel. Something to think about, I imagine.

[…] imagination and the completeness of its world-building. It vaguely reminds me of Hope Mirrlees’s Lud-in-the-Mist in the way it builds a convincing community, complete with a collective imagined history and set of […]

[…] the great modernists. But it’s worth remembering that Hope Mirrlees, who wrote the great fantasy Lud-in-the-Mist in 1926, was also a consciously modernist writer. And, to me, having read only To the Lighthouse […]

I was in high-school in the 70s when I read this book (with the first shown cover). By then I had consumed much F&SF, and a little sword&sorcery, too. It was clear this was not Tolkien (but “Smith of Wootton Major” has some of the same flavor), or Lord Dunsany, or William Morris, or any of the moderns. I thought of Prohibition, forgetting that the author was of England. But at the time, much experimenting in eating other than food was going on, although not amongst those I knew, and we all heard of it. As for Duke Aubrey s pleasure-house, I thought not much of venery, and I doubt that Hope Mirrlees really meant that, or only that, for I had read of many other things done under that heading. In “Sherlock Holmes”, for all the stories of young women in trouble, there are hints of that.

I had not heard of Jane Harrison; we had a copy of “the Golden Bough”, but none of the little that I read there bore on this. I was impressed by Mirrlees s describing how “golden apples of the west” becomes cussing. It seemed so right.

I no longer have the book; at a yard-sale that I held I let a friend buy it for $0.1, and miss it.