Murray Leinster’s “Runaway Skyscraper”

I’m a nut about the trivia of dates, so the moment I heard about the birth of my second nephew, A. Dean Martin (yes, really), I had to look up the famous people who share his birthday of June 16. The list includes philosopher Adam Smith, legendary film comedian Stan Laurel, and Apache leader Geronimo. Oh, and some fellow named Murray Leinster.

I’m a nut about the trivia of dates, so the moment I heard about the birth of my second nephew, A. Dean Martin (yes, really), I had to look up the famous people who share his birthday of June 16. The list includes philosopher Adam Smith, legendary film comedian Stan Laurel, and Apache leader Geronimo. Oh, and some fellow named Murray Leinster.

It was that last name that struck me the most. Murray Leinster is one of those science-fiction masters who has managed to find a place in general public obscurity. Despite a writing career lasting over half a century, Leinster’s name probably means nothing to most casual readers of contemporary science fiction, unless they pick up anthologies of Golden Age stories.

Murray Leinster (pen name of William Fitzgerald Jenkins, 1896–1975) is a rare case of a twentieth-century science-fiction author whose career started before the Campbell Revolution in Astounding but also continued through and beyond it, into the era when Astounding had become Analog and the field had broadened with The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and Galaxy. Like Jack Williamson, Leinster shifted easily into the stable of authors that John W. Campbell corralled for Astounding, which was otherwise made up of newly discovered writers. Leinster wrote some of his best work for Astounding, most notable among them “First Contact,” a story which the Science Fiction Writers of America voted into the classic 1970 anthology The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One, meant as a “Nebula Awards before there were Nebula Awards.” “First Contact” tied for fourth place in the list of stories with Theodore Sturgeon’s “Miscrocosmic God.” Its inclusion in the collection marked it as one of the greatest short stories in the field pre-1965.

(By the way, The Science Fiction Hall of Fame is back in print. If you’ve never read it, go get it now; it’s part of of any “SF&F Essentials Bookshelf.” It was crucial in my development as a speculative-fiction reader when a friend loaned me his copy in high school, specifically telling me to read “Surface Tension” by James Blish. Thus did I also end up meeting Stanley G. Weinbaum, Theodore Sturgeon, Cordwainer Smith, Clifford D. Simak, Fritz Leiber, and Alfred Bester.)

Murray Leinster goes further back in time than most SF authors who participated in the Golden Age. His first science-fiction story, “Runaway Skyscraper,” was published in 1919. Not only does that pre-date the John W. Campbell Astounding by almost twenty years, it predates the first magazine dedicated to science fiction (Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories) and the term “science fiction” itself. The nascent genre was still known as “scientific romance,” I name I happen to love and still apply to some science-fantasy stories. At the time, readers who enjoyed these types of stories that combined super-science and adventure had to scour through the general interest pulps, such as All-Story and Argosy, to find them.

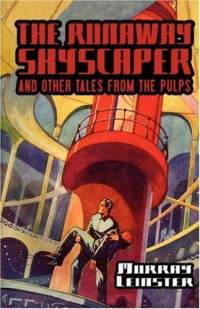

It was in Argosy that “Runaway Skyscraper” first appeared, in the 22 February 1919 issue. Amazing Stories reprinted it in its June 1926 issue. (Most of the early issues of Amazing were crammed with reprints). The story is a gem of early SF looseness, and since it is in the public domain, you can go read it for free on Project Gutenberg right now, or download it to whatever electronic reading device you have. For those of you who prefer paper, it’s available in the volume Runaway Skyscraper and Other Tales from the Pulps.

It was in Argosy that “Runaway Skyscraper” first appeared, in the 22 February 1919 issue. Amazing Stories reprinted it in its June 1926 issue. (Most of the early issues of Amazing were crammed with reprints). The story is a gem of early SF looseness, and since it is in the public domain, you can go read it for free on Project Gutenberg right now, or download it to whatever electronic reading device you have. For those of you who prefer paper, it’s available in the volume Runaway Skyscraper and Other Tales from the Pulps.

A title like “Runaway Skyscraper” makes a smash hit before the first paragraph. Leinster must have sold the story to Munsey Magazines before the editor even looked at the first page. As New York was about to going into a skyscraper construction boom, with crews competing to see who could hurl up the tallest building the fastest, interest in super-tall structures was high. In 1919, the Woolworth Building was Manhattan’s — and the world’s — tallest building, but Leinster’s “Metropolitan Tower” in the story is obviously meant to be the Metropolitan Life Tower, completed in 1909 and briefly the world’s tallest building until the Woolworth building superseded it in 1913.

The intriguing title of course begs the question: what would make a skyscraper a “runaway”?

It turns out that “Runaway Skyscraper” is a time-travel piece that places itself as a semi-sequel to H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine. Wells’s concept of “the fourth dimension” in his famous first science-fiction novel gets trotted out to explain the strange events that occur to the Metropolitan Tower and its tenants.

The simple explanation is that a small earth tremor causes the tower to sink just enough that it shifts into the fourth dimension, causing it and the two thousand people inside to start moving backwards in time at an increasing rate. The tower continues its trip until it stops approximately three thousands years in the past, on a Manhattan Island inhabited only by early hunter-gatherer Americans.

Later in the story Leinster expends time trying to explain how the time-shift occurred — something involving a geyser beneath the building — that makes just enough internal sense for a reader to shrug and move forward. I could ask questions like: Why did the building stop at that specific point in the past? Why the acceleration of time instead of moving at a constant rate? What would happen if someone in the building tried to leave it while it was moving? Would they still be subject to the building’s backward movement? How did the building’s foundation displace the matter already present in the past? Even with the foundation, wouldn’t the building have no support in the softer earth around it and topple over?

Leinster gets around these issues with a shrug, and blurry phrases like: “He simply knew that in some mysterious way . . .” In 1919, this was acceptable.

So like most early SF, “Runaway Skyscraper” won’t stand up to scientific scrutiny, even from someone like me who prefers “softer” forms of science. I think the fifth-grade version of myself would have spotted the holes. But Leinster’s story holds up and foreshadows the style of the Golden Age with how it realistically handles the reactions of the tower’s tenants when they find themselves trapped in the past. The attention to survival tactics, the twentieth-century castaways’ attempts to build a working society in their new home, and the shifting of power among the survivors all show Leinster thinking out the consequences of his science-fiction ploy in a way that feels much like classic Heinlein. The coda involving an economic ploy using a time-travel loophole would fit very well in Heinlein’s “Future Earth” series. The science is fuzzy, but the story isn’t a basic adventure.

But Leinster does take the “romance” part of “scientific romance” seriously, and weaves a love story into the tale. The hero, engineer Arthur Chamberlain, has never had the moxie to make a move on his attractive stenographer Estelle Woodward. Once stranded in the past, Chamberlain’s natural leadership wins Estelle over and he can at last find the willpower to ask her to marry him. It isn’t done in a sappy moment, either, but with a deft bit of comedy.

The story’s most interesting character is banker Van Deventer, who finds that the struggle to survive in the past is more an adventure than a terror: “I never planned anything like this before . . . and I never thought I should, but this is much more fun than running a bank.” In general, “Runaway Skyscraper” is in tempo with Van Deventer’s remarks: there is tension, but optimism and human ingenuity prevail. This attitude most marks the story as a product of its time, at the opening of the aspiring ‘20s.

When I read stories from the infant days of magazine science fiction, I feel a mixture of nostalgia and naivety. There’s purity and joy to work like this, when so much remained to be discovered in a field with only a few writers. There’s also many moments of head-smacking silliness. But the very best of the early work, such as “Runaway Skyscraper,” can survive on the quality of the writing and the sincerity of the writer. As early as 1919, Murray Leinster showed that he had the penetrating mind and the entertaining wordsmith skills the carry him through the Golden Age and into the New Wave.