A Lone Candle In A Dark Passage

It’s a cliche from the horror genre: a character (almost invariably female), ill prepared for misfortune (as her flimsy nightgown demonstrates), ventures down a newly discovered secret passage. She is wary, but determined, holding aloft her sole source of illumination.

A candle.

We find ourselves wanting to shout “Don’t go down that passage!” Or at least demanding she pause for sensible footwear, a better source of light, a weapon or two, and, time permitting, more clothes.

But we know something she doesn’t: her genre. We know that, as a horror story character, she’s setting herself up for a very bad time indeed. There’s no way I’d do that, we tell ourselves. No freakin’ way.

But, of course, we do similarly things all the time, tempting fates in ways that our fears cry out against. In blackouts, we fumble around in our basements looking for candles. We wedge ourselves into crawlspaces and attics looking through old boxes. We take shortcuts through dicey neighborhoods and across rickety bridges. We hear creaks in the house at night, and roll over and go back to sleep. And we do so with some confidence, because most of us aren’t in a horror story.

We know our genre. That’s one of the differences between us and the characters we watch and read. They just think they know.

As consumers, readers of fiction and viewers of film, we are almost never given the luxury of discovery when it comes to the genre of a piece of work. We like some genres, and don’t like others, and don’t want to waste time or money on the latter. That makes sense, right? Maybe, but sometimes a dose of ignorance can produce profound effects when it’s finally lifted.

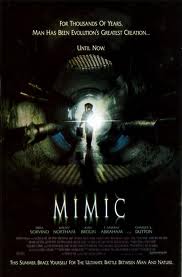

Let me give an example. (And yes, there are spoilers ahead.) Years ago, I went to a movie called Mimic, knowing absolutely nothing about it. The setup started with street people disappearing, and a mysterious figure lingering motionless in the background of a few scenes, watching. The setup was pure psycho-killer, a maniac terrorizing a city. It fit with the vague impression I was getting from posters, if I remember correctly. I began to expect a disquieting police procedural, ala Se7en. A madman, a nameless figure to be hunted down by the forces of the law.

Until the shadowy man unfolded into a huge flying creature and grabbed a character in a subway tunnel. It wasn’t a psycho killer at all, but a man-sized type of insect whose species had developed a number of adaptations allowing them to prey on humans by crudely mimicking their physical stance and demeanor. That moment, when the dark human figure transformed into a monstrous inhuman creature was pure cinematic gold. Like the characters themselves, I was completely taken aback, not sure what was happening.

I often wish that we would allow for such genre-induced surprises in our lives, at least in the realm of escapism. The unknown genre offers a lot of potential power to a story, but also have a number of problems. The most obvious is that of kicking the crutches of genre conventions out from under the reader. It’s odd to think about how much of our storytelling, and the suspension of disbelief, stem from knowing what the conventions of the genre are before the story begins.

As a writer, I know that genre-blending must be brought to the fore immediately. Trying to thread the needle of writing without violating a genre’s modus operendi can be hard enough, but with an unannounced blend, you’d have to keep from violating either genre’s strictures. And the payoff is also mostly for a select group of readers. Romance readers frown on a supernatural agency unless they have chosen that sub-genre to read. They also frown on sudden graphic violence, tragic loss, and alien abduction, unless they are fans of those particular sub-genres.

I tried such a feat long ago with a short story called The Wind I Once Followed, in which a team of federal marshals in post Civil War America is tracking a stolen military pay shipment in the western territories. I built up the uneasy alliance between a white former slave owner and his multi-ethnic group, trying to engage in the complexities of ethnic relations in that situation, especially as they close on their quarry, and their danger mounts. The resolution involves an Indian myth of hellish supernatural justice meted out to thieves who kill for gain. The sudden change from one genre to another happens “off-screen” with the characters just hearing awful things, and then slowly seeing the inexplicable. The possibility of a natural cause for these events fades in the reader’s mind, allowing them to accept what they “see” at the story’s conclusion. It is clearly supernatural.

Or is it? I was careful to set up an alternative explanation involving infection, delirium, and medical overdoses, but still, the imagery was mythic, and the story doesn’t disavow it, as an historical piece should have, nor did I fully set the stage for it, as a horror or supernatural thriller would have. Readers liked it, but editors usually said it was poorly plotted, or made use of deus ex machina or similar. My careful work in setting up one genre in order to introduce another failed.

So is there any genre of entertainment in which such a thing might be more welcome than it is in film or fiction?

Short story writing was our last hope, you whisper.

No, I say. There is another.

To be continued.

I’m safe because I have a flashlight! Classic!

[…] This is a continuation from Part 1. […]